“I was attracted to melodic bass players like Carol Kaye. Why should a rock bassist play dumb notes all the time?” How Tony Visconti rethought rock bass for David Bowie’s The Man Who Sold the World

The legendary producer revisits his ground-shaking bass work on Bowie’s 1970 breakthrough album

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

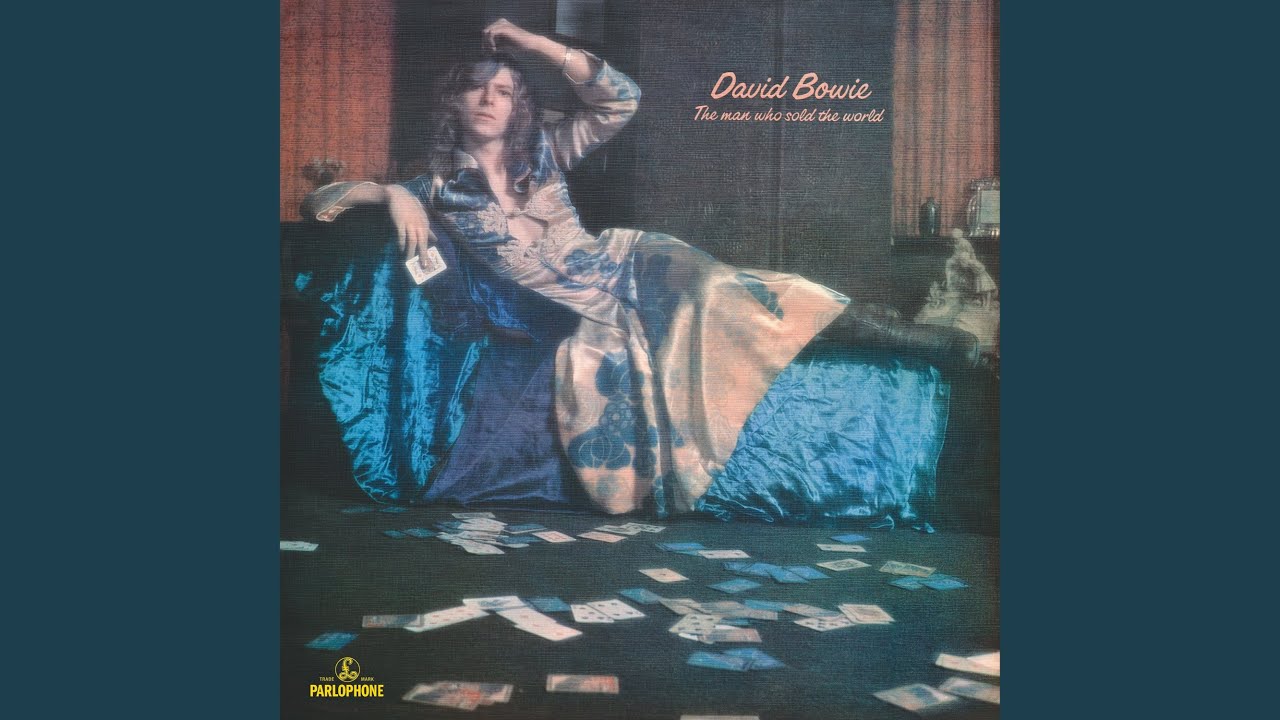

It didn’t skyrocket to the top of the pops – thanks, in part, to Machiavellian intrigue by a certain artist manager – but David Bowie's 1970 epic, The Man Who Sold the World, nonetheless became one of the touchstones of the glam era.

It also established Tony Visconti, working from a platform established by earlier pioneers such as Paul McCartney and Jack Bruce, as a co-conspirator in the quest to elevate rock bass playing beyond merely articulating root notes.

Visconti's bass on The Man Who Sold the World dances all around the music, adding countermelodies, harmonies, and solos in a thrilling onslaught. Even more exciting, his basslines are loud, and they're loud long before urban artists began begging mastering engineers to pump up the low-end on their discs.

Visconti – a street-smart, classically trained jazz musician from New York – was technically and conceptually well-equipped to innovate, but a couple of other pieces had to lock into place before the sonic barrage of The Man Who Sold the World came to be.

Bowie's band for the album included guitarist Mick Ronson, whose love of Cream and Jack Bruce fuelled a desire to crank up the bass in big ways, and drummer Woody Woodmansey, a combination of a more elegant Keith Moon and a ballsier Ginger Baker, who provided Visconti with the rhythmic fusillades to explore wilder and more intricate basslines.

In one of those little gifts of fate, the ‘power trio’ of Visconti, Ronson, and Woodmansey unleashed a high level of musicianship while simultaneously introducing a fiercely rocked-out Bowie to a public who had previously known him only for Space Oddity.

“We started to live together in a big apartment in Beckenham, Kent, and that's where we rehearsed for the sessions,” Visconti told Bass Player back in 2016. “We worked out about half the album down in a converted wine cellar that acted as our rehearsal space.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“It was there that my basslines were starting to get developed. I didn't quite write them down, but I organized the parts in my head. The other songs were written in the studio.”

How did the musical relationship between you and Woody develop?

“We jammed in the cellar and felt each other out. Woody is a very intuitive drummer, and I'm a very improvisational bass player, so it worked great in the studio, because we were making up our parts as we went along.”

In your musical life before meeting Bowie, who were your influences on bass, and how would you typify your style at that early stage?

“When I first started playing bass, I was a double bass player. In high school, I was a member of the All City High School Orchestra, where I played Schubert's First Symphony, and pieces like that.

“So I was already influenced that the bass has a strong voice where you played the bottom lead line. It wasn't like rock ’n’ roll at the time, where the bass always played the root note.

“Shortly afterward, I was drawn to jazz players such as Charlie Mingus and Scotty LaFaro. Mingus because he was very uninhibited-a wild man on bass – and LaFaro because he was one of the first lead bass players in the jazz field.

“I thought I was going to be a jazz musician, so I bought a Fender Jazz Bass. When I started to drift back to rock, I was attracted to melodic players like Carol Kaye, James Jamerson, and Paul McCartney. I thought, Why should a rock bassist play dumb notes all the time – stay down there and play G, G, C, C, E, E?

“When The Man Who Sold the World first exploded out of my tiny record player, I remember it as one of those albums where my young ears went, ‘Wow, the bass is really driving the songs.’ When I hear it today, I'm embarrassed. I wish I could remix that album – let's put it that way.

“But I'm glad the bass came into prominence at that time, because Jack Bruce did pave the way for lead bass playing. Mick Ronson was the one who wanted me to mix the bass up real high – not in all of the mixes, but definitely on songs like Width of a Circle.”

What do you think prompted Mick to want the bass like that?

“He loved Cream flat out, and because we were a power trio, I was expected to fill a lot of space. Also, from the start, we decided to let everyone have an equal voice. Everybody had to show themselves off to their best abilities, and that was the theme of the album – no holds barred.

“So Mick made the suggestion that I should be a bit more adventurous. He asked me to cut loose. He totally approved of me, and he was quite ruthless. He had already fired the drummer, because he wasn't up to his standard.

“And quite frankly, David and I wanted someone more adventurous – like Ginger Baker – because we were playing in odd time signatures, which was my forte. That's when Woody came in.”

What was the recording process like?

“I followed Mick's lead and turned everything full up! We were playing extremely loud –ungodly loud – and our amps were about 20 feet to the left and right of Woody. I wore headphones more for ear protection than to hear David's vocals. David was the only one in an isolation booth.”

“In those days, we went for live takes. If you made a mistake, you'd do another live take until the band played it perfectly. If they were cool mistakes, you'd leave them, because they were a ‘feel’ thing. You didn't put your finger in exactly the same place at the same time? So what? What's the big deal?

“Obviously, there's a lot of signal bleed when you do live takes playing that loud, and that made punching in at a later date almost impossible. But the mentality of fixing your parts wasn't popular back then, anyway. It was looked upon as cheap and amateur-ish to want to punch in and keeping punching in.

“We also felt it was a waste of time. We weren't opposed to splicing two takes together to get the best of each. Oh, and no one would play with a click track – that was for chumps. But, to be honest, now I can't live without one.”

Do you remember the gear you brought in for the sessions?

“I had a 200-watt Wem tube bass amp with two Wem 2x18 cabinets. It had a black-plastic front, with controls for volume, bass, middle, treble, bass boost, and treble boost – and it was loud. By then, I had sold my Jazz Bass, because it didn't have the low-end, it didn't give me enough highs, and it didn't rock.

“So I bought a Fender Precision. But when I switched from playing with my fingers to a pick, I missed the bottom-end. I wanted it to rumble. I had luthier Roger Gitten put a Telecaster Bass pickup on the P-Bass with a toggle switch. Then, I could switch between the P-Bass pickups and the Tele pickup, which would rumble the way I wanted when I played with a pick.

“Roger did another modification for me in the mid 1970s, installing two DiMarzio pickups near the bridge, adding active circuitry for treble and bass and a toggle switch, and carving a cavity in the back to accommodate a 9-volt battery.

“The Precision is only on a couple of songs on The Man Who Sold the World: She Shook Me Cold and Width of a Circle. For a lot of the other songs, I used a borrowed Gibson EB-3, because we were getting back to Mick Ronson's insistence that I sound and play like Jack Bruce.

“I also had an 8-string Hagstrom bass, and an Ampeg Baby Bass that I used for a lot of the bowed and pizzicato parts.”

Chris Jisi was Contributing Editor, Senior Contributing Editor, and Editor In Chief on Bass Player 1989-2018. He is the author of Brave New Bass, a compilation of interviews with bass players like Marcus Miller, Flea, Will Lee, Tony Levin, Jeff Berlin, Les Claypool and more, and The Fretless Bass, with insight from over 25 masters including Tony Levin, Marcus Miller, Gary Willis, Richard Bona, Jimmy Haslip, and Percy Jones.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

![David Bowie - The Man Who Sold The World [2020 Mix] [Official Lyric Video] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/u3MX-rUtS6M/maxresdefault.jpg)