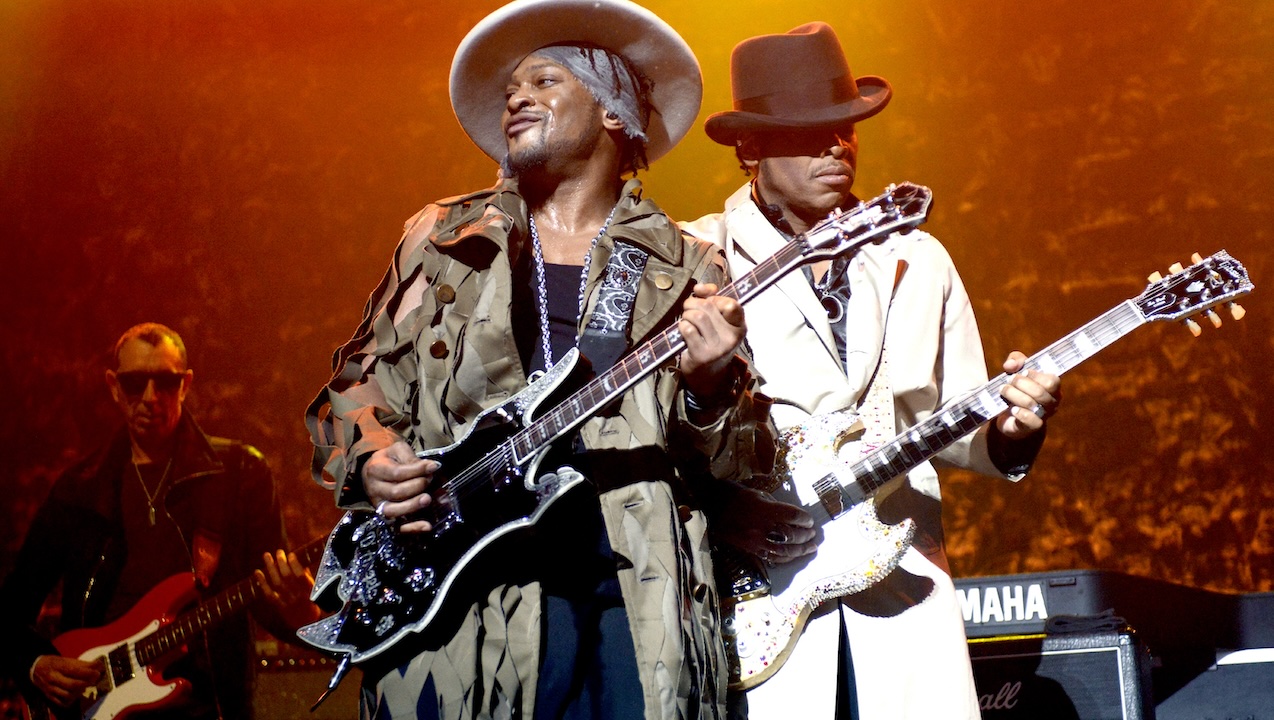

“We hit it off right away. He saw me playing my '63 P-Bass and said, ‘That's a Bootsy bass, right?’” How a chance meeting between Pino Palladino and D’Angelo helped create the sound of the late neo-soul legend's Voodoo album

The A-list bassist sheds some light on the late R&B legend's beguiling behind-the-beat hip-hop grooves

Pino Palladino first entered the bass world's collective consciousness with his soaring, melodic fretless basslines (sometimes bolstered by a Boss octave pedal) on hits such as Paul Young's Everytime You Go Away, Don Henley’s New York Minute, and Chris DeBurgh's Lady in Red.

Before long, he became one of the most recognizable and imitated fretless players of his generation – and undoubtedly the most mimicked in his genre.

As the fretless craze died down in the 1990s, Pino re-emerged as a roots R&B-loving grooveaholic who was in his element with neo-soulers like Erykah Badu, Musiq, Roy Hargrove, and the late D'Angelo, while maintaining his steady schedule of mainstream sessions.

“I've always loved rhythm, and I loved the sound of the bass guitar and the role it takes in the music,” Palladino told Bass Player back in March 2004. “The whole concept of not playing much but having a big impact.”

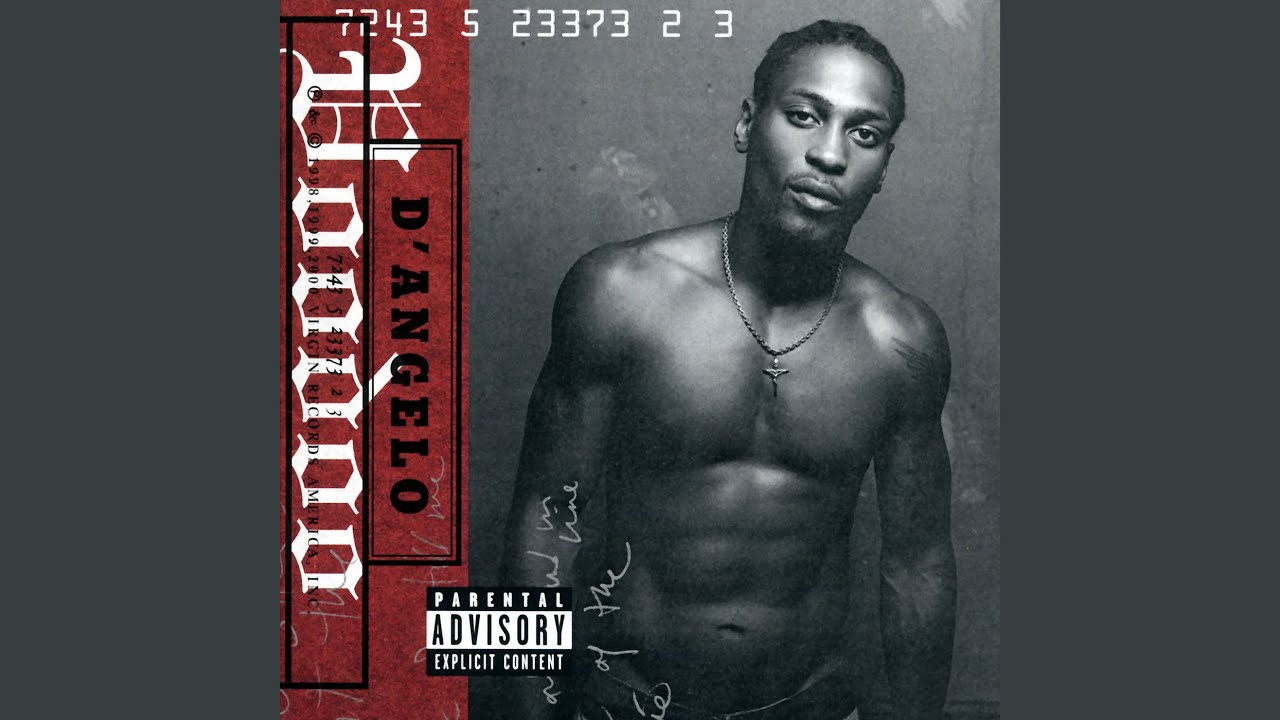

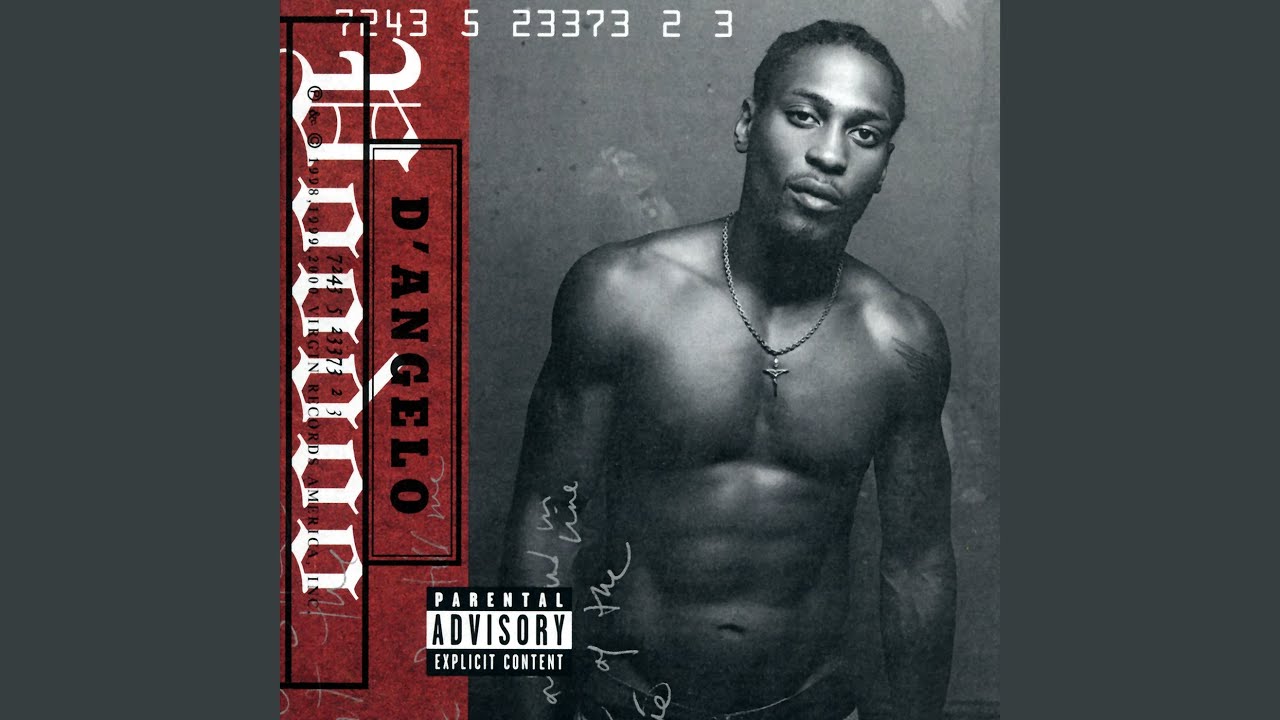

D'Angelo's Voodoo saw Palladino ease into a vintage-fretted vibe, evoking the spirit of James Jamerson with spontaneously improvised variations-on-a-theme basslines that sat loose and way back in the pocket.

“The only way I can play that style of bass – really hanging back – is for the drummer to sort of ignore what I'm doing. The tension is created by the drummer keeping the beat strongly in the middle and maybe even pushing slightly. If the drummer tries to hold back with me, the tension is gone.

“It's something D’Angelo and Raphael Saadiq got from hip-hop – where the samples are not always in perfect time, creating a certain sloppy feel – which they incorporated into the way they feel music.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Pino's bass playing on Voodoo is a world away from the sinewy melodies of his ‘80s fretless efforts. Listen to Send It On for a line that is both melodic and glued to the kick drum, and Chicken Grease for a stuttering rhythmic funk groove.

“I like to feel the snare just on the edge of pushing, and then I can sit back in a certain space that makes the groove wider. It's not about listening to the drummer and playing an instant later; I'm still locking with the drums, but I'm feeling the groove in a different rhythmic dimension.

“Actually, that loose feel has always been around; I don't think it's anything new, really, but D's take on it and the way he arranged it on his tracks is the key – he brought it to the next level. For whatever reason, I took to the feel completely, and I felt fortunate to get it first-hand from one of the originators.”

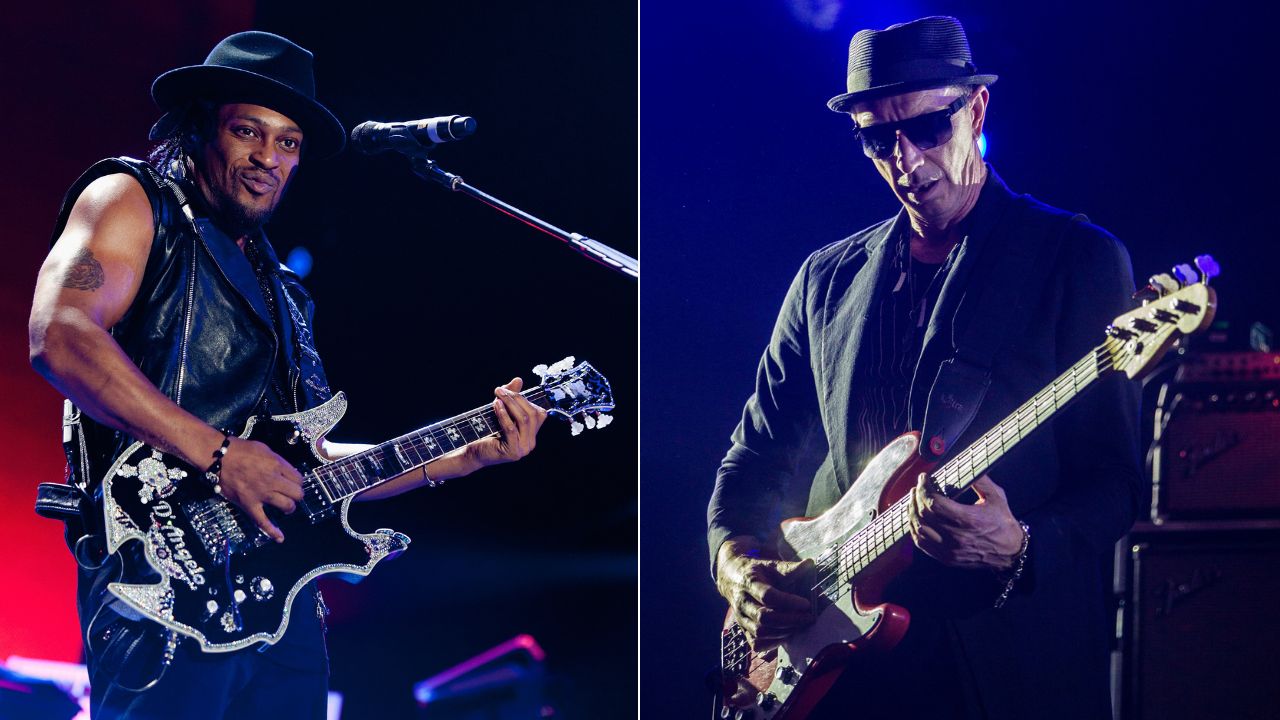

When did you hook up with D'Angelo?

“We met in 1997 while doing a track for B.B. King's Deuces Wild, and we hit it off right away. Whenever he sang, I played better!

“He saw me playing my '63 P-Bass and said, ‘That's a Bootsy bass, right?’ I said yes and mentioned that James Jamerson also played one, and he went crazy over that. It turned out the Jamerson/Bootsy/Larry Graham approach I'd been focusing on was the concept he wanted. He just said, ‘You've got the sound I'm looking for – come and play bass on Voodoo.”

“That was incredibly fortunate, because it also led to sessions with a variety of other hip-hop artists, and the formation of the writing team with D's sidemen, James Poyser and Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson.”

How did you all come together on the D'Angelo groove?

“It was a meeting of minds and influences and sounds, but the feel is 100 percent D’Angelo; you can hear it all when he sings and plays keyboards. He hears everything in his head before he records a note, and his concept has the drums right on the beat – almost pushing – with the keyboards and bass hanging back in their own places.

“When we first recorded he'd explain how far back he wanted me, and it felt pretty natural. I'd just try to lay back with the keyboards and listen to the overall feel. Still, there were times when I'd wonder if it was too far back – if people would get it. But when he'd finish putting his vocals and sound collages on top, the whole track would work splendidly.”

How did you record and perform the bass parts?

“D comes up with amazing bass parts in his left hand. He would play me about 80 percent of a line, and the remaining 20 percent was open to my interpretation. My approach, which he encouraged, was to constantly develop the line with subtle variations, à la James Jamerson.

“Another key is that Ahmir's drumming is very Motown-like; he leaves plenty of room for the bass because he just plays straight, heavy time, without a lot of fills. What's interesting is both D and Ahmir are pure hip-hop artists, so everything has a swung-16th-note feel.

“Ahmir can take that old swung soul feel and give it a contemporary sound by adding an edginess to the beat that didn't exist back then. The three of us cut all the scratch rhythm tracks as a trio, and in most cases I ended up replacing my part later, with D.”

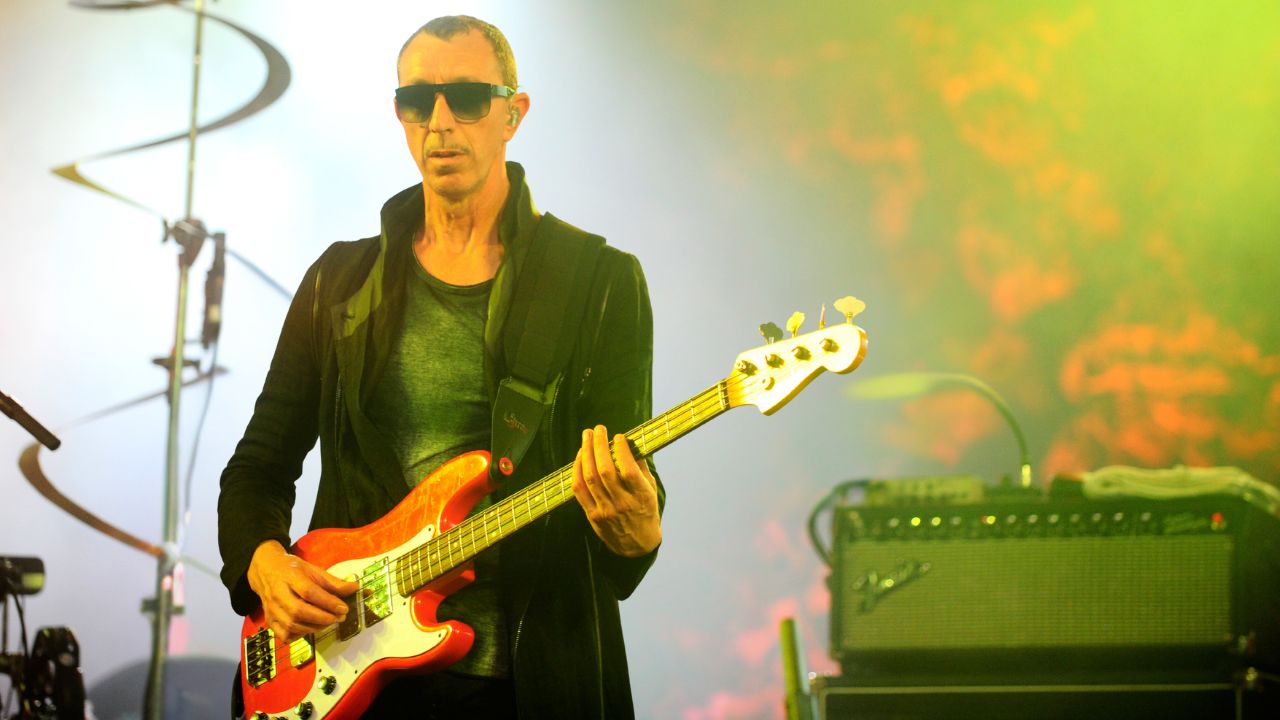

What equipment did you use to record, and to play live?

“I played either my '63 P-Bass tuned down to D or my Moon Larry Graham signature 4-string tuned down to C#. Both had heavy-gauge La Bella flatwounds, which can be rough on necks; that's originally why I tuned down the Precision.”

“I plugged into a miked Ampeg B-15, and I'm pretty sure that was the only signal we took. I've also got my Boss octave pedal, which I used on one track. Live I use the P-Bass tuned to D, a Lakland Joe Osborn tuned to C#, and a Moon 4.”

Considering your fretless legacy, was this a new direction for you?

“The fretless phenomenon was something that just happened, and I'm grateful for it. I got to work with a lot of amazing people on an instrument I loved playing, and I developed much of my vocabulary on it – especially in the higher register. But R&B is what's in my heart, and D'Angelo is a very special artist. He has helped to bring back some great music at a time when it's truly needed.”

Nick Wells was the Editor of Bass Guitar magazine from 2009 to 2011, before making strides into the world of Artist Relations with Sheldon Dingwall and Dingwall Guitars. He's also the producer of bass-centric documentaries, Walking the Changes and Beneath the Bassline, as well as Production Manager and Artist Liaison for ScottsBassLessons. In his free time, you'll find him jumping around his bedroom to Kool & The Gang while hammering the life out of his P-Bass.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.