“I got a call from Glenn Frey. I just said. ‘Where do I sign?’ Here they were asking me to join the Eagles without playing one lick of music with them”: Timothy B. Schmidt joined the Eagles at the height of Hotel California – and didn't even audition

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

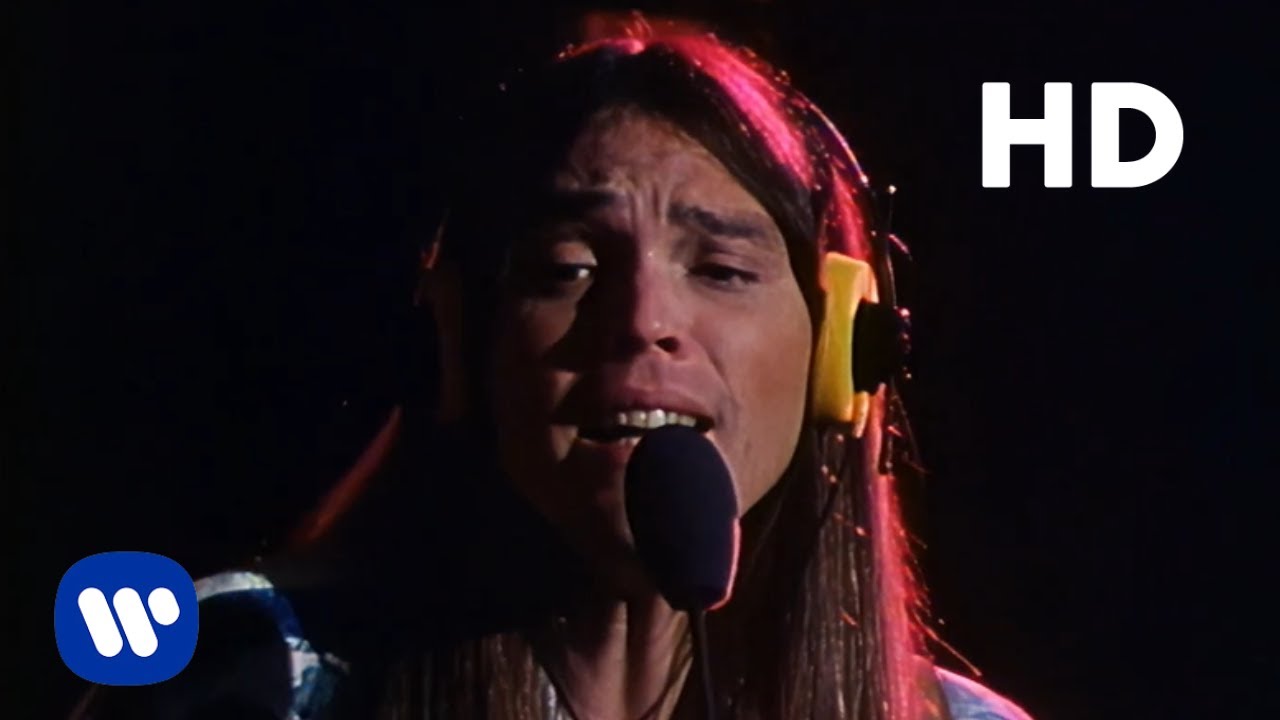

From his childhood years tagging along with his musician father in the family's ‘Expando' trailer home to his seven years in the saddle with Poco (country-rock's boldest pioneers), Timothy B. Schmidt has logged more miles than even the toughest road dogs. Of course, most know him as the high-tenor-voiced bass guitar man for the Eagles.

Schmidt got his Eagles wings in 1977, on the tail end of the band's blockbuster Hotel California tour, and went on to record 1979's The Long Run, the last album before the band split in 1980. The Eagles re-convened in 1994 for Hell Freezes Over, and again in 2007 for Long Road Out of Eden.

But Schmit's varied career goes far deeper than just the Eagles or Poco. In his 1980s downtime, he hit the road with Jimmy Buffett's Coral Reefer Band, and he has worked as a session vocalist for artists as wide-ranging as Steely Dan, Toto, Bob Seger, Poison, Tim McGraw, and Spinal Tap.

“I consider myself a singer first, and a rather basic bass player. I'm really an accompanist,” Schmidt told Bass Player. “There are guys who play bass like a lead guitar, but that's way beyond my comprehension and abilities. Sometimes they go so far that it doesn't even seem like bass anymore. To me, the bass should hit you low; it's the foundation.”

“You can make a mistake on a piano or guitar riff. But if you're off by a fret on bass, everybody turns and looks at you. So it's pretty important. There are a lot of non-musicians who may know nothing technical about music, but who will certainly know it if you take the bass out of a piece of music.”

None of that kept Schmit from consistently delivering high-quality solo albums, starting with 1984's Playing It Cool, and continuing with 2022's Day By Day, certainly Schmit's most self-assured, mature offering to date.

“It still amazes me that I get to do what a I do. I've had a really exceptional career, which I'm still pretty mystified about and grateful for.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

The following interview from the Bass Player archives took place in August 2010.

How have you managed such a long and successful career?

“In some ways, I have no idea. That would be my honest answer; I'm not trying to be overly humble. I have talent, but there are people out there with way more talent. So there's a certain element of serendipity in how my career has evolved. But as far as work goes, I think I have more hustle in me than I realize.”

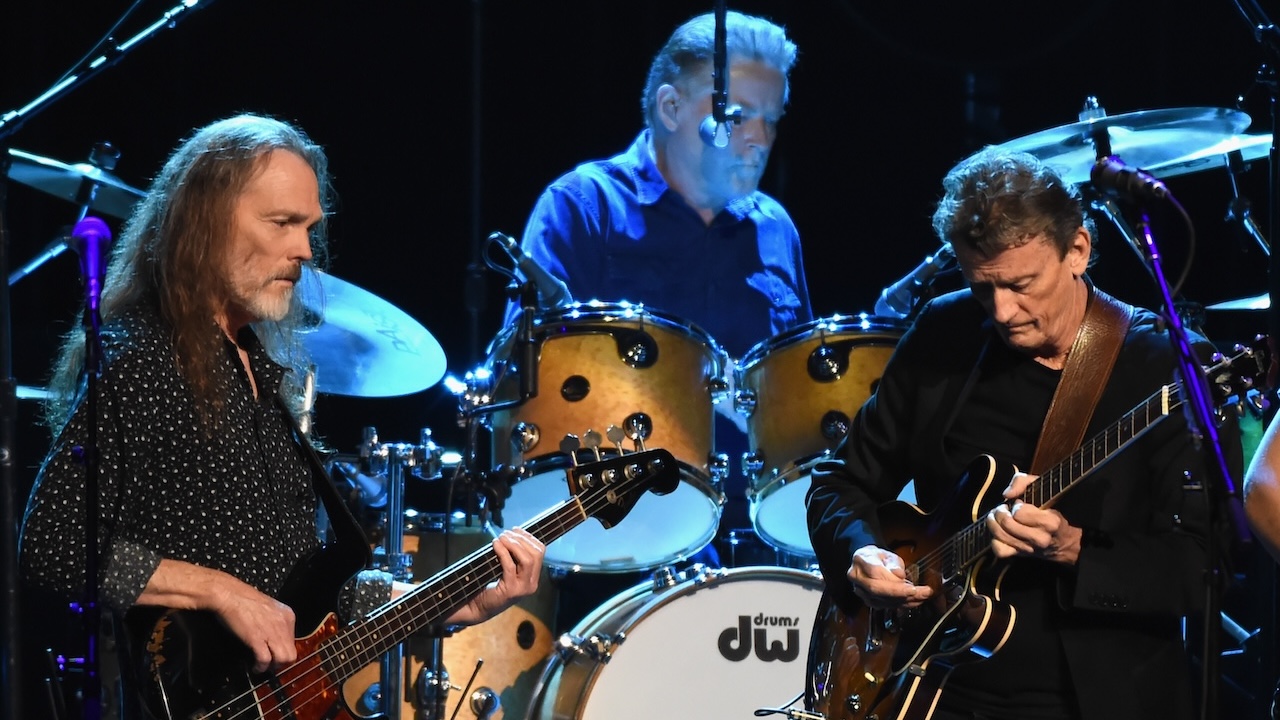

How did you first get the call to join the Eagles?

“Poco had levelled off in popularity, and I was becoming a little disenchanted with it all, so I began to put out feelers to determine my next move. I had met Eagles manager Irving Azoff through things like working with Steely Dan, and I think he brought my name up to Don Henley and Glenn Frey when things with Randy Meisner started to fall apart.

“A little while later, I got a call from Glenn asking if I was interested in joining the band. I just said. ‘Where do I sign? How soon can we do this?’ Here they were asking me to join the band outright without playing one lick of music with them.”

“I was really happy when we had our first rehearsal, just because I wanted to really feel it. Up to then it had all felt like science fiction. Right from the time I heard of the possibility of my becoming an Eagle, I thought that it was an ideal fit. And I don't mean that in a cocky way.”

To your ears, what were some of Randy Meisner's strongest moments in his tenure in the band?

“He's on their first six albums; he's the one that was in the trenches. He obviously had a beautiful voice, he was a real decent bass player, and he was just part of that whole movement. I have a lot of respect for him.”

When you first joined the band, how did you adapt to your new surroundings?

“I really was careful. I knew there were some pretty large egos in the band and obviously huge talent. I watched gingerly for a while to see where I'm going to fit in sociologically, and as a player. And I'm pretty good at that – I'm perceptive about people and situations, and I'm not a big trouble maker. I'm the guy who wants things to work out, so we didn't have any problems.”

In what ways, either general or specific, have you come to put your own stamp on those bass parts that were there before?

“The Eagles have always been sticklers for making things sound just like the records. So I didn't have too much wiggle room when I joined, because I pretty much copied parts. I knew I was copying them, and that I didn't make them up.

“When I did my first studio album with the band, The Long Run, I got to run with my own ideas. That was really satisfying. But I have no problem with playing Randy's parts, and I have no illusions.”

Of the many sessions you've done, do any stand out as supremely satisfying?

“I would say Steely Dan – almost anything I sang on there. That was the first time I ever heard myself on the radio nearly every hour with that song Rikki Don't Lose That Number. Those sessions were great because their music is so truly awesome – and I don't use that word lightly.”

Do you have a hard time playing when you're singing?

“No, I don't. If I'm learning a new piece or working something out for the first time, I'll work on it until it becomes second nature, but I have a pretty good work ethic, because I don't want to appear like I don't know what I'm doing.”

“For instance, in 1992 I got a call from Ringo Starr, who wanted me to play in his band. We had a long list of tunes to learn, but nobody knew which ones we were going to actually play. So I learned them all. I just sat learning the songs and picking out the parts I would probably be singing.”

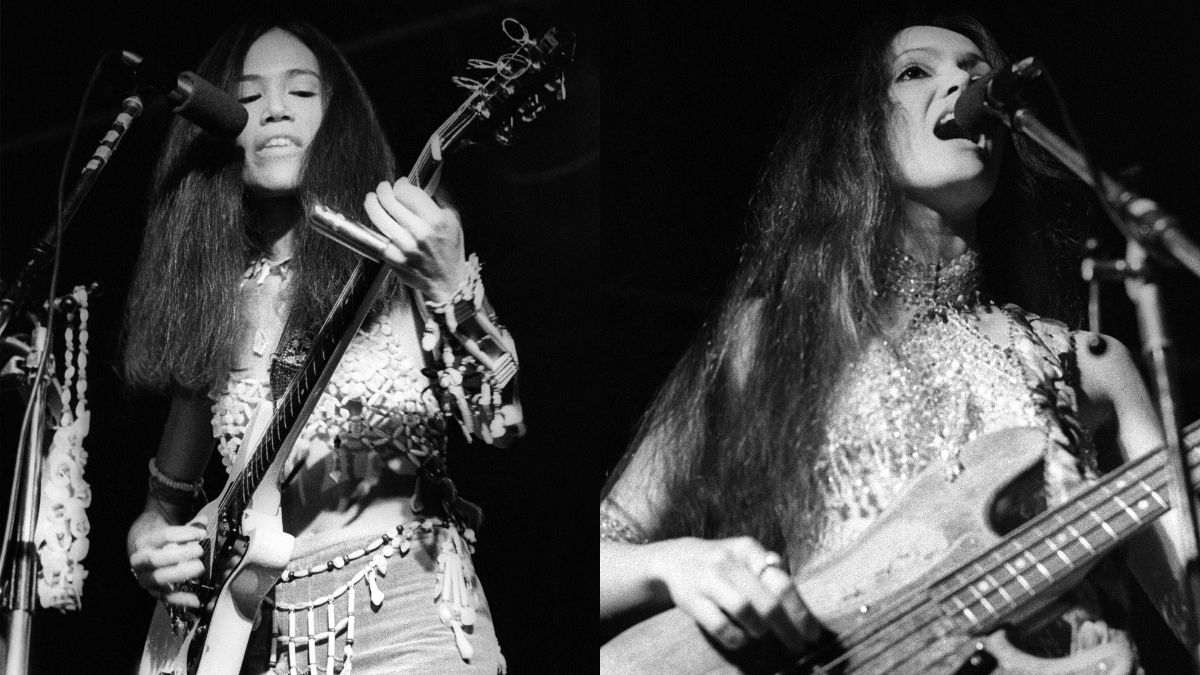

Poco is often cited as being the first authentic country-rock band. In terms of your own contribution, how do you view that legacy?

“With Poco, there was a great energy onstage, but there was some weirdness offstage. But that's like every band, right? Towards the ends of our shows we used to stretch out and do some actual jamming. I always really enjoyed that, but it’s hard for me to listen to old Poco now. It feels really young and unsophisticated, at least in terms of my contributions.

“There's nothing wrong with that – it's like going through an old photo album. It can be a really strange experience and you can get hung up on it. But I don't want to do that with music. I really try to look forward.”