David Gilmour Talks Guitars and New Album, 'Rattle That Lock'

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

If David Gilmour had not become the guitarist for Pink Floyd, he probably should have sought a career as the Director General for MI5.

The man can certainly keep much more than a saucerful of secrets better than most, and he runs a very tight ship when it comes to keeping information about his own activities under a tightly closed lid.

During this age of social media, paparazzi and tabloid journalism where every private moment is exposed and scrutinized in detail, Gilmour has kept a surprisingly low profile for a rock star of his legendary stature. He even managed to keep news of The Endless River, Pink Floyd’s first studio album in 20 years—and the band’s very last—under wraps until only a few months before its release in November 2014.

While Gilmour was a little more forthcoming recently with information about his work on a new solo album, details were scant until a few months before that album’s release as well.

The process of hearing Gilmour’s latest solo album, Rattle That Lock, before its official release date was no easy feat. Dates constantly shifted as Gilmour made ongoing tweaks to the mix, and apparently the CD had to be hand-carried via courier from the studio in England to Sony’s New York office as online transfer could leave the precious material susceptible to hackers. Even before I could hear a note of new music, I had to sign various contracts promising not to divulge so much as the most abstract perspective or ordinary detail prior to an agreed upon date, and the album’s liner notes could only be examined during the listening session.

Looking over the notes in the listening room, I noticed that the cast of supporting characters was almost identical to Gilmour’s 2006 solo effort On an Island: lyrics by Gilmour’s wife Polly Samson, orchestral arrangements by Polish conductor Zbigniew Preisner, co-production and guitar by Phil Manzanera, and instrumental support from the likes of Jools Holland, Rado Klose, Guy Pratt and Robert Wyatt, amongst others. Even David Crosby and Graham Nash contributed background vocals to one song once again.

However, the overall sound of Rattle That Lock is quite different from anything that Gilmour has done before, both as a solo artist and with Pink Floyd. The mood is surprisingly upbeat on several songs, and the lyrical content is quite mature, retrospective and, in several instances, intimate and personal.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

The album’s title track has a breezy pop feel, and Gilmour’s lead vocals are almost unrecognizable from his usual plaintive, soulful wail. “The Girl in the Yellow Dress” is an even further departure with its mostly acoustic lounge jazz arrangement, while “In Any Tongue” goes in completely the opposite direction with a tense, immense and almost symphonic sound that perfectly complements the lyrics’ violent imagery. However, one particularly familiar element of Gilmour’s past work remains present: his soaring, emotive guitar solos, which are plentiful throughout most of the album’s 10 tracks.

Interestingly, once I worked my way through the preliminary gauntlet and was finally able to speak with Gilmour, the shroud of secrecy finally appeared to be lifted. The man is quite jovial and forthcoming, although the duration of our conversation was limited due to his extremely busy schedule as he was still working on fine details of the final mix before sending the album out for mastering. While Gilmour will turn 70 next year, his motivation and work ethic put most musicians less than half his age to shame, and his vocal and playing talents have actually improved since the last time he released a solo album.

Gilmour is also touring for the first time in almost a decade, but this time around the pace will be more leisurely so he can still enjoy time with his family at their seaside home in Hove on the south coast of England near Brighton. What Gilmour’s next step will be beyond the tour is unknown, but it certainly won’t have anything to do with Pink Floyd. The death of keyboardist Richard Wright in 2008 and the completion of the band’s last unfinished work, released on The Endless River, brought Pink Floyd to its final closing chapter. Even so, Gilmour will still be keeping the band’s music alive through his concert performances of numerous songs from the Pink Floyd catalog.

While Gilmour says he was finished with Pink Floyd a long time ago, this is the first time that his actions speak—to borrow a song title from the last Pink Floyd album—louder than words. Rattle That Lock is Gilmour’s first solo album that sounds more like an expression of his true self rather than an extension of his former band. Whether fans will get to experience more dimensions of Gilmour’s personality now that he is completely free from Pink Floyd is difficult to tell, given the long periods of silence that usually transpire between his albums. The man does know how to keep a secret, after all.

GUITAR WORLD: This album really delivers a lot of surprises, especially for people who have known your work for many years.

I hope so.

Did you set out with specific ideas for this album or are you always working on songs?

I’m always working. The pot gets fuller and fuller and fuller quite slowly over a few years. Then I realize that it’s going to be an album and I start planning and moving forward. But I can’t honestly pinpoint the moment that that happened with this one.

The material is quite a nice variety and very different from what we’ve heard you do with Pink Floyd.

It’s a bit more upbeat than my last solo album. I don’t have any explanation for that. The gifts that we are given are the ones that we accept.

Does your wife Polly write lyrics first and then you do music for them or is it the other way around?

Usually I have some pieces of music and I work on them in the studio. Then I bring them home, play them in the house, and she gives me her opinions on things. Sometimes she says, “I really like that one. Would you like me to have a crack at the lyrics?” And I say, “Yes please, my darling.” Then she moves it on from there.

Do the two of you collaborate on the general focus or themes?

She usually manages to find out what the story is all about. She might say, “If we were to go in this direction, how would you feel about that?” So far I’ve always said, “That sounds terrific to me.” She manages to be quite telepathic at knowing what I want. These days she’s feeling more liberated and feels good about following her own instincts more than she would have done a little earlier. If I believe in something and sing it, it will become my song, so she doesn’t have to worry about looking at things through my eyes anymore.

That’s interesting, because most of the lyrics come from a very authentic male perspective, whether it’s a father or son. Even “The Girl in a Yellow Dress” seems to be written from the male eye.

That one is more of a third-party perspective. It’s a story that could be told by anyone. “In Any Tongue” is a weighty and powerful lyric, which she felt was a very male subject. But she’s managed to put herself into those characters. I don’t know which other ones you think are male. I think they’re more universal.

“In Any Tongue” really hit a vein of what is going on now. We have a lot of very angry young men who are striking out at the world. The lyrics really capture that mindset.

It captures that brilliantly, doesn’t it?

Your son Gabriel is playing piano on that song. What inspired you to have him record that particular song with you?

That song required a sensitive touch on the piano.

Gabriel learned how to play piano from a teacher and went through the grades with it. He got tired of us beating his knuckles and wanted to stop, but about three months after that he decided he wanted to play piano on his own.

He learned pieces of music from Doctor Who by ear and played them brilliantly. If there is a piano anywhere near, you’re pretty sure to find Gabriel playing it. I just asked him one day if he’d consider playing piano on that track. He has a beautiful touch.

That song is a dramatic shift in mood from the rest of the album. The production is bigger, and the bass is much deeper.

I’ve had bits of that song for quite a few years. It was always a bit elusive to determine how to move it forward. It took me a few years to find the way. Then one day it all suddenly suggested itself and came together. It was the last song to get a lyric. Polly was very unsure for a while about how to do it. She wasn’t sure that she could put herself into the male perspective enough.

She managed to find a way, and when she decided to free herself from her restrictions on that she just moved on.

“The Girl in the Yellow Dress” is a 180-degree shift from that. What inspired you to do a traditional jazzy song like that?

I don’t ever want to turn anything away when it arrives. Those chords just started pressing themselves on me one day quite a few years ago. I recorded a backing track with a jazz trio back then. Again, I couldn’t quite find a way forward for it. These songs kind of struggle and fight their way to the top of the pile.

They present themselves to me and say, “Now is my moment.” That’s what those two particular songs have done. A solution gets found at the right moment, and they move into top gear. I don’t know how to describe it exactly. It seemed as if it was too much of a change in mood for the album, but I felt that my voice was enough of a unifying factor to tie it in with the rest of the album.

There are two other guitarists on that song—Rado Klose and John Parricelli.

Rado was known as Bob Klose, and he was the guitarist in a very early version of Pink Floyd. His father worked with my father in our hometown. I’ve known him since I was born. He’s a real jazz player. He left Pink Floyd when he realized that it wasn’t going to suit him and he wasn’t going to suit it. He quit very early on, but he’s still a friend. I thought it would be fun to get him to play on that song with John Parricelli, who is a great jazz guitarist in England.

I didn’t play any guitar on that song for years. I ended up just putting a tiny little bit of noodling right at the end because I thought that I can’t have a song with two other guitarists on it but not me. [laughs]

There is a saxophone solo on that song instead of a guitar solo, too.

The sax player is Colin Stetson, who is an American guy. He’s brilliant. Terrific sax playing on that.

In addition to people you’ve worked with previously like Jools Holland, Robert Wyatt and Rado Klose, it seems like you’ve built a strong support team with people like Phil Manzanera, who you’ve worked with quite a bit over the years. What does Phil bring to what you do?

He’s a great sounding board. He’s a great archivist as well. He has tons of my little demos, and he’s very happy to spend a long time listening through them for little ideas and making suggestions about how to use them or put two or three pieces together to create a song out of things that have slipped by me. Two songs on this album come from him finding bits and putting them together for me.

What would be examples of that?

“Faces of Stone” came from two ideas of mine, and he put together “Today” in a similar way. They’ve sort of changed beyond recognition since then, but that’s where they started. He is terrific company, and he’s always listening, making suggestions and being part of the team. He has no ego. He’s a great guy.

Did “Rattle That Lock” start with Michaël Boumendil’s SNCF (National Society of French Railways) train jingle?

That’s where the musical inspiration came from. Polly did the lyrics later. The jingle is just a great little syncopated piece of music that you hear at train stations in France. Every time I’d get off of a train in France I would hear that. It makes you want to jig a little bit. [laughs] I recorded it with my iPhone in a station somewhere and took it home and wrote the song around it.

I read that Boumendil’s specialty is developing “audio identities” for companies. It’s an interesting concept.

Yes it is. Trying to say something significant in four or five notes is quite a tough call.

Your vocals sound very different on that song. I almost didn’t recognize it as being you.

No, that’s me, along with Mica Paris and Louise Marshall as well singing backup along with the Liberty Choir. There are quite a few extra voices in there, but the main lead vocal is me.

It’s a very upbeat way to start the record, and it prepares the listener for this being a very different album for you. Did you always plan to have it that early in the sequencing?

Yes. This has been the easiest album to sequence that I’ve ever made. Songs just suggested where they should be in the whole order of things. We haven’t changed the order for ages. It was decided early on and we assumed that’s how it would be. We are open to change, but it wasn’t necessary.

You recorded this album at several different studios.

We worked at the Gallery, which is Phil’s studio, my two studios Medina [Gilmour’s main studio in Hove, England] and Astoria [his famous houseboat studio in Hampton], and AIR’s Lyndhurst studio in Hampstead, which is George Martin’s studio and where we did the orchestra sessions.

Do you work on a song in total in a particular studio, or do you move around?

These days I use Astoria mainly as a mixing room. All the mixing is done there along with some finalizing, such as last-minute vocals. Most of the recording on this album was done at my Medina studio, which is where I work away on my own for months and months on end. Phil does some of his work at Gallery.

What is the Medina studio like?

It’s a short distance away from my house. I found a building and we converted it, building rooms within rooms like you need for a proper studio. There are separate recording and control rooms. Most of the time it’s just me in the control room working away on the computers. I love Pro Tools. The control room doesn’t even have a proper desk. Most of the microphones are hard-wired into the computer. I just open up a track, select the right track number, and the microphone will be there. There’s a set of tracks that are always used for the drum kit, so that’s all set up and ready to go at any time. I can record drums without an engineer being there, and hopefully they’ll be close enough that they’ll just need some adjustment in the mix. The piano has two mics on it, and they go direct to two inputs. The guitar amps go through a separate external mixing board. I just go to that board and select which amps and which mics I want to use. That all comes down to two or four channels. It’s all quite cleverly designed to be a one-man operation. It’s so liberating. It’s brilliant for me to have a system like that.

What are your main amp preferences these days? I notice that you’ve added an Alessandro to your collection of Hiwatts and Fenders.

I used the Alessandro [Bluetick Coonhound] for the solo on “Louder Than Words” [on Pink Floyd’s The Endless River]. I have a Hiwatt 2x12 combo [SA212] that I like to use, along with some tweed Fenders [Champ, Tremolux, Twin] and Yamaha rotating speakers [RA-200] that I use for some things.

In recent years it seems like you’ve been using different guitars like Gibson Les Pauls and Gretsch Duo-Jets more often.

I’m using the black Gretsch Duo-Jet and Gibson Les Paul gold top with single-coil P-90 pickups on some of the album. I still play the black Strat a lot. I’m using my old “workmate,” as I call it, 1955 Fender Esquire on some of the solos—“Rattle That Lock” and “Today.”

Do you have a preferred amp and effect setup for your solos?

It changes all the time. I’m always trying different things, and sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn’t. I have used a (Chandler/B.K. Butler) Tube Driver with a compressor for most of my overdrive-type stuff in recent years. I have several different compressors—a Demeter Compulator and some MXR and Boss compressors—and my preferences always change. I haven’t used a Big Muff for 20 years now, I suppose. On some of these solos I only used a compressor with a little bit of delay. I ran the compressor’s output volume hotter than usual for some overdrive. I use whatever I can if it sounds nice. I change all the time, to be honest.

Your attack in particular is quite fierce. It’s like you’re digging into the string instead of just scraping it.

That’s because I tend to play more with my fingers these days. I often find myself not using a pick at all. I’m not really sure why or what difference that makes. I guess it makes a bit of a difference in the sound. I really like the tone, but I play even slower, and I’ve never been all that fast to begin with. There you go! [laughs]

Have you made any significant new gear acquisitions?

No. I can’t think of anything that’s all that new beyond the Alessandro amps. I’m still using two different Martin guitars for my acoustic stuff, one of which is the same D-35 guitar that I used to record Wish You Were Here, and the other is a 1945 Martin D-18, which I’ve used a lot over the years.

You’re going to be doing your first tour in almost a decade. Will your live setup be different this time around?

I haven’t even gotten around to thinking about that yet, to be honest, so I don’t have any idea what I’m going to be using. We’ll have to see. I literally just finished mixing the album, and I haven’t moved on yet. I’m very bad at concentrating on more than one thing at a time. The next thing on my agenda is to start planning out how all of that will work.

There’s some very nice nylon string/classical guitar at the end of the album on the track “And Then…” What did you use for that?

I bought a nice classical guitar when I was recording “High Hopes” [from The Division Bell], but I’m afraid I don’t know what make it is. It’s a nice one though.

This album seems very personal in nature, and it’s also a departure from what you’ve done with Pink Floyd.

There are a lot of different topics, most of which obviously come from Polly. I’m really reveling in my work and my partnership with Polly at the moment. She always has a comment to make about everything, and she’s usually worth listening to. She is maturing into a first-rate lyricist, and it’s a privilege to work with her. I’m looking forward to moving on and doing more.

Speaking of moving on, with The Endless River you closed the final chapter of Pink Floyd. The album was a very fitting final tribute and farewell to Rick Wright.

I think so too.

Did the end of Pink Floyd have any liberating effect on your work on this album?

For me that chapter had closed a lot longer ago than most people would think. I decided a very long time ago that that part of my life was over. We’d make the occasional slip, like Live 8, but The Endless River was something that really deserved to be finished. It was the last of any remaining, unfinished tracks that we had, and anything we had of value was on that album. It was truly the end of Pink Floyd.

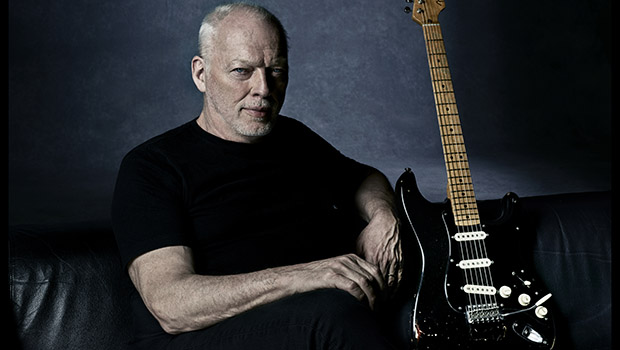

Photo: Kevin Westenberg

Chris is the co-author of Eruption - Conversations with Eddie Van Halen. He is a 40-year music industry veteran who started at Boardwalk Entertainment (Joan Jett, Night Ranger) and Roland US before becoming a guitar journalist in 1991. He has interviewed more than 600 artists, written more than 1,400 product reviews and contributed to Jeff Beck’s Beck 01: Hot Rods and Rock & Roll and Eric Clapton’s Six String Stories.