The Last Days of Hair Metal: George Lynch, Warren DeMartini, Lita Ford, Reb Beach, Phil Collen and Nuno Bettencourt Look Back

“It was just an incredible moment to be into the guitar." A round table of hair metal's giants looks back on the genre's final days.

“There was a real excitement about that time,” says former Ratt guitarist Warren DeMartini about the 1980s. In particular, he adds, “It was just an incredible moment to be into the guitar. There was great stuff coming out from all over the place.”

Indeed, there was. Because while the electric guitar has been the foundation of rock ‘n’ roll for well more than a half-century now, the instrument was never approached in such spectacular, pyrotechnic fashion — and to such mainstream commercial success — as it was in the Eighties. In the wake of Eddie Van Halen’s eruptive rearranging of hard rock guitar circuitry at the end of the Seventies, scores of flashy, insanely accomplished guitarists flooded the hard rock and metal worlds, achieving mass mainstream penetration on MTV, radio and the road throughout the following decade. Without a doubt, it was a great time to be a rock guitar fan.

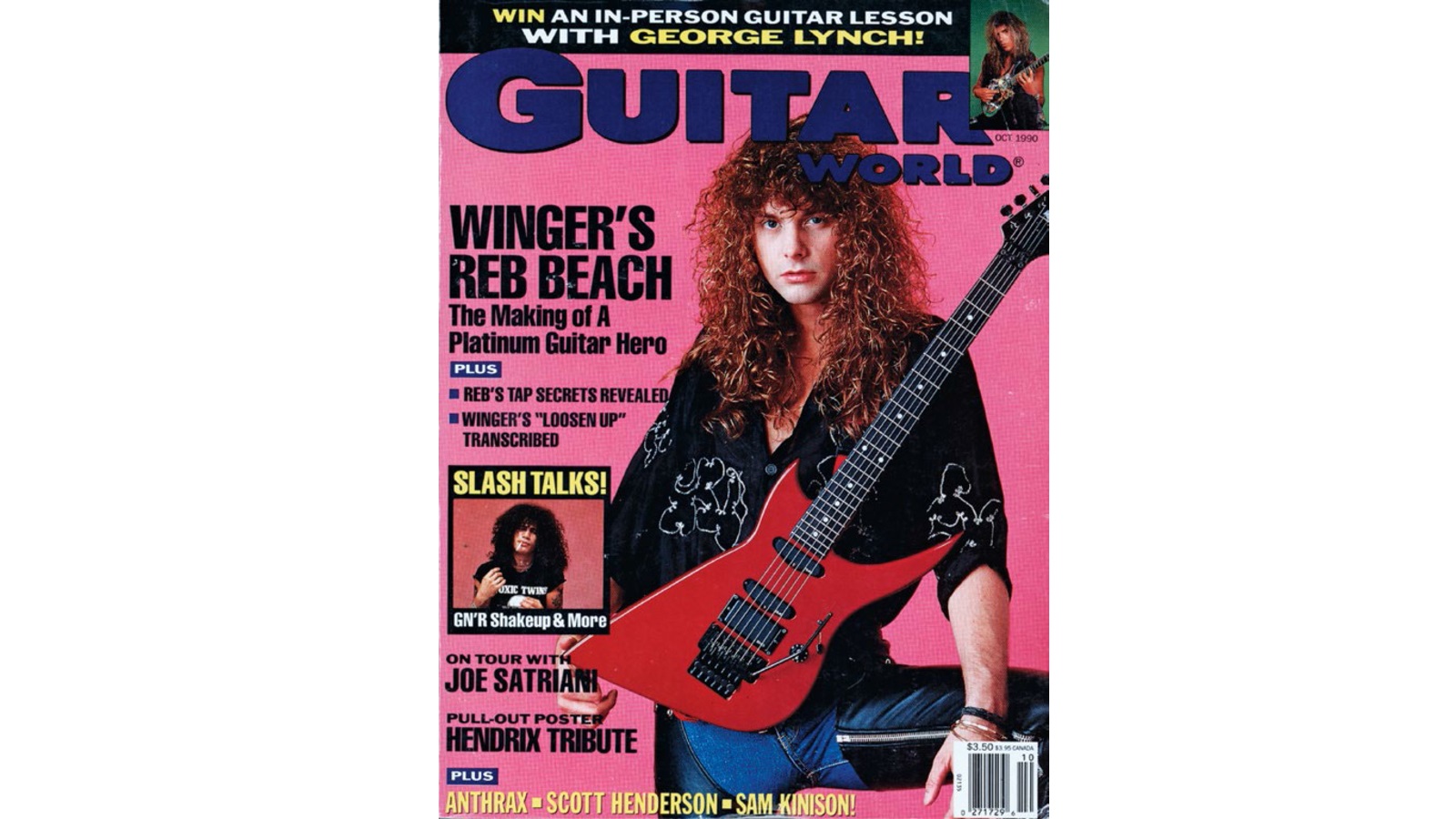

And, to be sure, a great time to be a rock guitar player. “There were girls everywhere and kids screaming for us,” recalls Winger hotshot Reb Beach. “We were selling lots of records, and everything was awesome. I was like a kid in a candy store. I was young and hungry. I looked amazing. I was living out every fantasy I ever had, and I was ready to take on the world.”

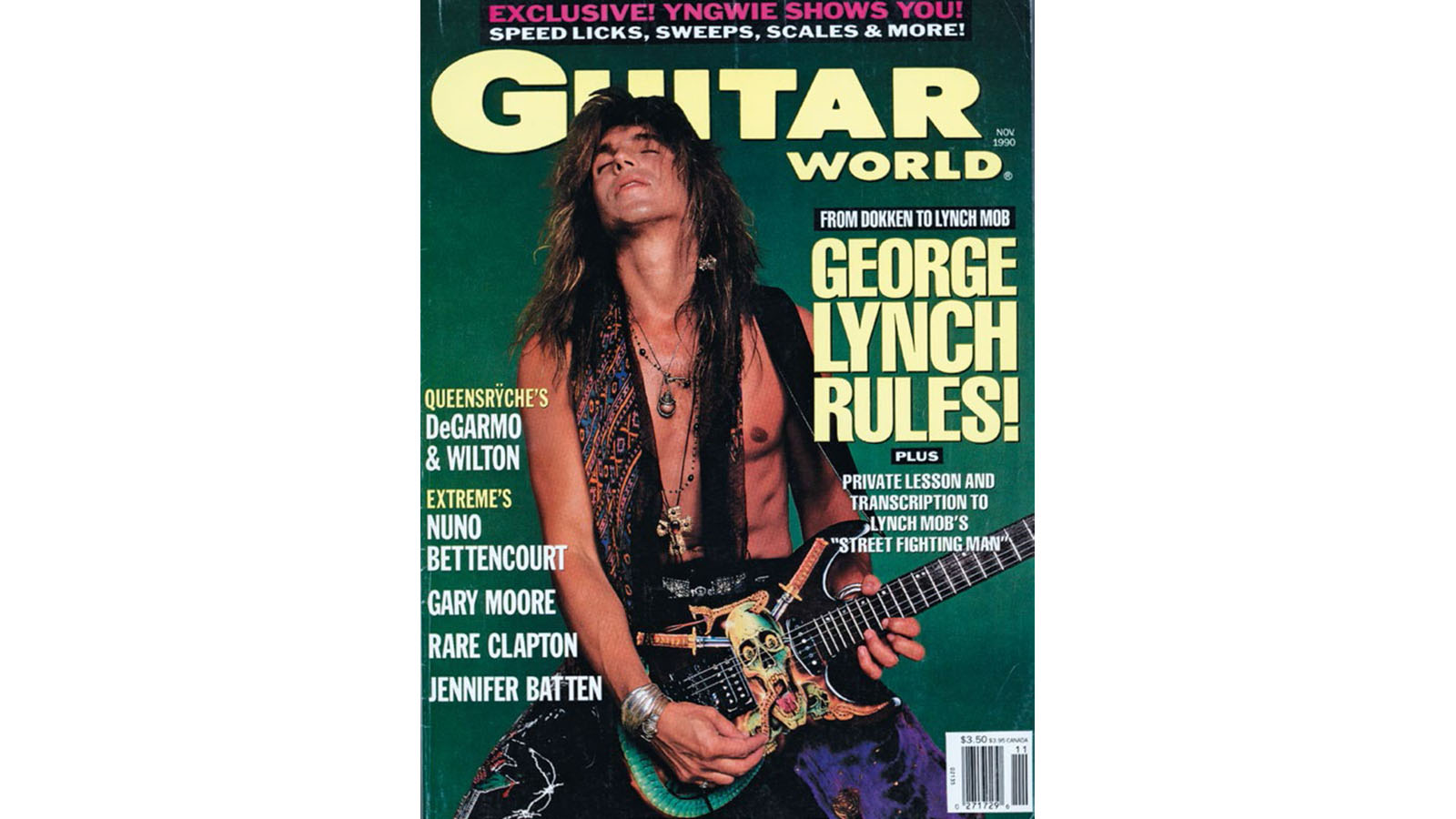

Of course, all good things must come to an end, and Eighties-style hard rock was eventually eclipsed by the less technically minded guitar sounds of grunge and alternative, or what former Dokken axeman George Lynch now calls “our collective Nirvana moment.”

In celebration of the decade of big hair and bigger riffs, Guitar World rounded up some of the era’s most beloved and successful players — DeMartini, Beach, Lynch, Def Leppard’s Phil Collen, Lita Ford and Extreme’s Nuno Bettencourt — to look back on a few of the highs and lows of the time.

And while they’re all still incredibly active these days — for example, Bettencourt has played with Rihanna and continues with his own band; Ford has been hailed as an influence on a new generation of rockers, including Halestorm’s Lzzy Hale; and Collen and Def Leppard just completed one of the most successful stadium tours of the year — all were happy to look back on the era when hard rock and metal, as well as the guitarists who wrote the riffs and ripped the solos, ruled the charts.

All of your bands were coming from a background where you were heavily influenced by Sixties and Seventies rock. Were you surprised at all when, in the Eighties, your music started being referred to as hair metal?

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

REB BEACH: I had no problem with it. That’s what we were. We had big hair and we wore cool clothes. I used to spend hours on my hair. I sprayed it with Aqua Net and made it as huge as possible. The bigger the better.

LITA FORD: I didn’t mind. I thought it was awesome! In the Seventies, guys looked like cavemen, but in the Eighties they got cleaned up and sprayed their hair up. People looked great, and it was an amazing time. Bands were booming, and everything was huge.

GEORGE LYNCH: I think that’s an imposed term. But rightly so. It’s a little bit derogatory, but I was just very appreciative that we were getting recognized at all. So I could handle all that.

PHIL COLLEN: I wasn’t really surprised. We were a rock band that was on MTV. It happens in any genre, whether it’s the punk movement in the Seventies with the Pistols and the Clash or us and Bon Jovi and Motley Crue in the Eighties. But then it gets watered down. You know, there were some really awful bands that we got lumped in with just because they were doing big videos and trying to copy the same snare sound. All of a sudden everyone goes, “Oh, yes — it’s the same thing!”

WARREN DeMARTINI: I thought it was a hostile term, you know? But I think it was something that was invented after the fact. The pattern seems to be that the people that own the newer art and are pushing that tend to trash the older art.

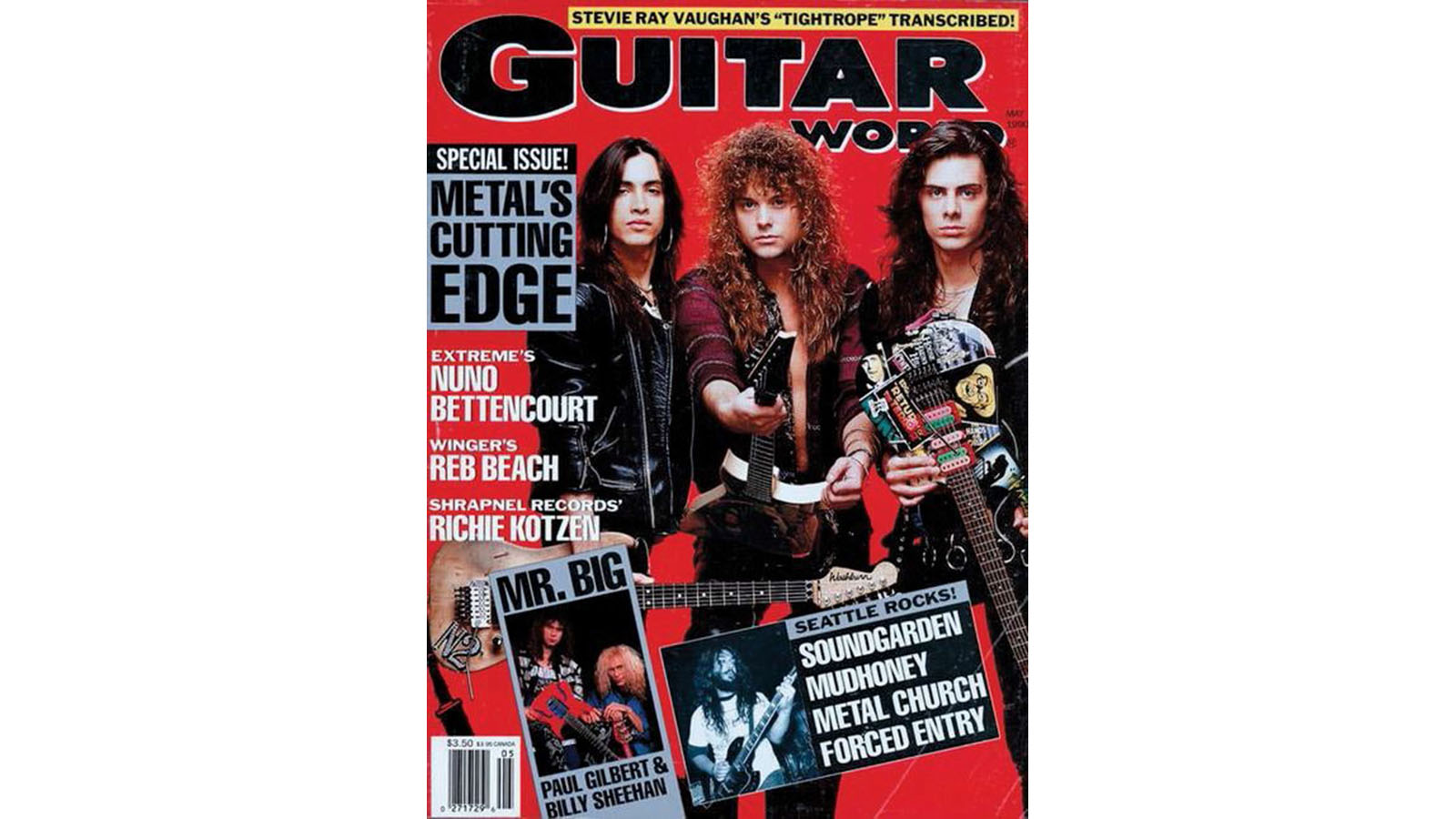

NUNO BETTENCOURT: I think we wanted to feel like we were part of the community, because we were a part of that era. So we had no choice. But we did try to be outside the box. We were definitely that redheaded stepchild of the Eighties metal era.

Did it seem as if there was a template for bands at the time, almost like a formula?

BEACH: Absolutely — and Winger went right along with it. I was the hot guitar player, and Kip was an awesome frontman. He looked gorgeous, and he did his spins. We were all shaking our asses in our videos — it was great! We put on a show. That’s what you’re supposed to do.

COLLEN: We never followed a template, because we saw so many bands and so many guitar players fail trying to follow it. I always thought that you’re supposed to be a team player. In Def Leppard, there was absolute respect for the song. A lot of bands missed that vital ingredient and it just became about, “Listen to me!”

LYNCH: It wasn’t like most of us had incredible far-sighted vision. It was pretty myopic reasoning. Watching relative to what every other band was doing and the way they were dressing and the songs they were writing and the sounds they were getting and the way they were shredding. Unfortunately, it worked its way to an apex that backed us into a corner with no place to go. Because you could only play so fast, and then it was, “Does it really matter?” And then Nirvana comes along and says it all with one nasty, dirty attitude note. And you go, “Ah, that’s rock ‘n’ roll!”

BETTENCOURT: We never felt pressure because I think our songwriting was mostly influenced by what had come in the past. Maybe the sounds were more current guitar-wise and production-wise, but we were inspired by the Aerosmiths and Van Halens and Led Zeppelins.

The songs and videos usually promoted endless good times. Were things as wild on the road as they seemed?

BEACH: Things were crazy! There was drinking and partying. Naked girls were everywhere. I remember there was this girl in a bathroom stall giving blowjobs. Word got out to the band and crew, and there was this line of guys waiting to get a blowjob. That kind of thing happened all the time. I remember L.A. Guns had orgies when they toured. You’d go on their bus and everybody would be naked. People were having sex right and left. It was very… inspiring. [laughs]

FORD: I used to see Poison pulling girls out of the audience, and they’d have so many girls backstage. They were liking freaking cattle! Girls were ripping their clothes off and throwing themselves at these guys. There was sex everywhere. I mean, I got it, but it did get a little too much. I just wanted to say to the girls, “Don’t act so stupid!”

COLLEN: On our Pyromania tour, which was our first tour, you’d have these really weird situations with women throwing themselves at you. But by the time of Hysteria, we dug in a little deeper and it became more about, you know, substance than substance abuse.

At any point, did it seem like the scene had become too excessive — too much partying, too much money spent on videos, too much everything?

FORD: Was there excess? Sure — some people died from it.

COLLEN: If there was any kind of partying or anything like that, we put it firmly in its place. All that does is get in the way of your art and your work. And obviously it killed one of us as well [guitarist Steve Clark passed away in 1991 at age 30 after a long battle with alcohol abuse]. At some point we had to grow up a bit.

BEACH: Our drinking never got out of control, but we definitely went overboard with our videos. Each clip cost $250,000, and we had to pay that back before we saw any money from Atlantic. It took me years to see a dime from our records.

DeMARTINI: It may have been excessive. But the thing is, it’s art, right? And you know, one of the things that MTV did was speed up the time it would take to get extreme exposure. Before MTV was around, it would take a lot longer for a band to get as big as Ratt got in one summer. So that had its advantages and its detriments.

LYNCH: Just as with how we felt an obligation to play really fast guitar solos, we felt an obligation to live up to the lifestyle. So I don’t know if one was mimicking the other or which came first the chicken or the egg, but either way it happened.

How important was having a power ballad? Do you think it hurt or helped your career?

BEACH: All of these bands were having hits with ballads, but as soon as they did, they were labeled a ballad band. We fought our label on releasing “Miles Away” because we knew it would happen to us. And that’s exactly what happened. We put out a syrupy video and things started going downhill.

FORD: The label never sat me down and said, “You need a power balled.” But they always tended to go for ballads as singles. That’s how you got on the radio. My duet with Ozzy, “Close My Eyes Forever,” went Top 10. It was Ozzy’s first Top 10 hit. That song just lit up the world, so I was okay with that. I wasn’t selling out. I had a hit!

LYNCH: It was just sort of the unwritten law. You had to have at least one, or it was a lost record. And you had to have a double-bass burner, one or two of those. And everything else was in the middle. When we were writing songs, we’d have our bpm’s up there on the board to make sure we had a variety of tempos. We had a formula, for sure.

DeMARTINI: For a long time Ratt really wasn’t interested in ballads, although later on we did start to appreciate them. But in those early days we just wanted to be on 10. We never wanted to slow down!

BETTENCOURT: I think every artist dating back in time, whether it’s composers like Beethoven or Mozart or anybody, they have their crazy shit, they have their mid-tempo shit, and they have their slow shit. Sometimes you’re jamming in a room and you write a song like “Play With Me,” because everybody’s hyped up, and then sometimes you’re tired and you pick up an acoustic and you sit on the porch and you write “More Than Words.” It’s not a formula that as a writer will ever change. Zeppelin did it, everybody did it. Well, maybe not AC/DC… [laughs]

![Def Leppard’s Vivian Campbell [left] and Phil Collen](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/skrMZidcwLadscqhxeAfiQ.jpg)

Who did you consider to be the best guitarist on the scene at the time?

FORD: It would be Eddie Van Halen, no doubt. He was the king.

LYNCH: There’s so many different guitar players I like for so many different reasons. But if you’re talking about the kind of music I was involved in, I guess it would have to be Eddie. He was the giant.

DeMARTINI: I liked what John Sykes was doing. And Jake E. Lee, to name a couple of guys.

BEACH: I would have to say George Lynch. I used to play Dokken’s Under Lock and Key all the time. It had the coolest soloing I’d ever heard next to Eddie’s stuff.

BETTENCOURT: For me, there were guys like Warren DeMartini and George Lynch, where I felt like, “Wow, this is kind of like Eddie’s thing but a step further and doing something a little bit different with it.” And Warren, you know, for a minute there I wanted to look like him. I wanted to act like him onstage. He impacted me.

COLLEN: I loved Slash’s playing. OK, it’s a bit sloppy, but the band is supposed to be like that, and he plays totally in context with that. And Guns N’ Roses had some really killer songs. And Steve Stevens I thought was amazing. The stuff he did with Billy Idol, he would always enhance the song. He doesn’t get enough credit for what he actually does, even to this day.

Do you have a favorite of your own solos from that era?

COLLEN: I really like “Stagefright” [from Pyromania]. That was the first thing I ever played in Def Leppard. [Producer] Mutt Lang said, “Take this song home tonight. Come in tomorrow and play a solo.” So I dug in and did this kinda Michael Schenker-type thing, and went off a little bit into an Al Di Meola shred thing. I used those two archetypes, if you like. And it was a one-take.

LYNCH: I have to admit, I actually don’t, because I don’t really listen to any of that stuff unless I need to learn it. I couldn’t tell you any of the names of the songs on any of those records or really remember the solos. But a few that I thought were cool were not necessarily the “hits.” Stuff like “Til the Livin’ End” or “Lightnin’ Strikes Again” [both from 1985’s Under Lock and Key]. Deeper cuts like that.

DeMARTINI: On the first album [Out of the Cellar], I thought “Round and Round” was quite good. From the second album [Invasion of Your Privacy], I would say “You’re in Love.” And it was exciting time for me because I had all these techniques and patterns but had never used them exactly in that way. So there was an element of coming up with something almost while I was actually recording it.

BETTENCOURT: I think the “Get the Funk Out” solo [from 1990’s Extreme II: Porno-graffitti] has a little bit of everything — the funk element, the tonal elements that I like, the technical elements that I like. If somebody goes, “Hey, what was your thing?” that solo is probably as good a representation as any of mine.

BEACH: I do a pretty intense solo on “Headed for a Heartbreak” [from Winger’s 1988 self-titled debut]. I remember Richie Sambora once said to me, “Man, you’re the luckiest guitar player in rock. My solos are five seconds long, but I heard that solo of yours, and it’s 30 seconds long!” I thought that was cool.

![Extreme perform in London in July 1992; [from left] Pat Badger, Gary Cherone, Paul Geary and Nuno Bettencourt](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/ryQFNgCcnae3x5x6QQgdPW.jpg)

When did you first hear the word “grunge”? Do you remember the moment when you thought, “It’s ending”?

BEACH: We had just released our [1993] record Pull. I told my wife, “I’m gonna be rich.” But then somebody gave us a tape of Beavis and Butt-Head. We popped it on, and there was the fat, uncool kid wearing a Winger shirt. I just went, “Oh, no… ” The next day, our ticket sales halted, album sales plunged. We had to cancel our tour. I had to sell my house and all my guitars. I went, “This grunge stuff means business.” The whole thing sucked.

LYNCH: Our collective Nirvana moment? For me it was a real gradual awareness that happened in the early Nineties. After Dokken I did a few records with Lynch Mob, and eventually sales declined to where it got to the point where we didn’t have a record deal. It was like, “Oh shit, what’s going on here? Do I need to get a haircut and stop playing so fast?” And then guitar became a thing you were ashamed of for about a decade.

DeMARTINI: There were new genres of music coming out all the time, but you could definitely feel that this sort of music had peaked and run its course, at least for that time. But it wasn’t just rock. Everything was changing. Hip-hop was getting more popular. MTV was playing less music videos. Everything goes in cycles.

BETTENCOURT: One of our first tours we did before we broke was with Alice in Chains. We were playing empty rooms in, like, Tijuana. So we felt like we were a part of what was happening, in a weird way, because we caught the end of the metal era, going into the Nineties. So we didn’t necessarily feel like we were in a music shift. At the same time, we were on the label [A&M] that also kind of broke the Seattle scene, with Temple of the Dog and Soundgarden.

Did you try to adapt at all to the changing musical climate?

BEACH: No. I didn’t like grunge — the music just made me sad. Why be bummed out all the time? I didn’t get it. Some bands tried to adapt, but we just kind of said, “Screw this” and broke up.

FORD: I just decided it time to get the fuck out for a while. Just step back and let these guys have at it. I loved Nirvana and those bands, but I wasn’t going to compete. I was ready for a break. When I came back, I really felt like the all the smoke had cleared, and I could do my own thing again.

DeMARTINI: No. It was always, “I’m gonna do what I’m gonna do,” you know?

COLLEN: We didn’t necessarily try to adapt to it, but we did try to do something different with our Slang record [in 1996], where instead of overdoing the production we took a very minimalist approach. And the songs were darker. Artistically, it was such an awesome album. So much fun. And the album wasn’t popular by a long shot. Quite the opposite, actually. But we loved it and a lot of fans really like it because it’s just different.

LYNCH: I think rather than trying to adapt, I just realized I was free to explore other things. It wasn’t like I was trying to mimic grunge music or anything else that came along as much as I was just trying to listen to the other stuff that I already liked and maybe wouldn’t have played 10 years earlier. But anything I wrote and recorded was for the most part pretty much hard rock music.

BETTENCOURT: We weren’t really chasing it, but I think we were influenced by the way those records were produced. Things didn’t sound so slick. I remember hearing a Pearl Jam record and telling Gary [Cherone, Extreme singer], “I wanna fucking do that.” Just the way it was recorded…

Anything you wish your band had done differently?

FORD: No. We gave it our best shot. Nirvana, Alice In Chains, Stone Temple Pilots — they kind of stomped on the Eighties groups. All the rock stars were gone, and everyone looked like they’re just construction workers. But it was what it was.

BEACH: Nah. I like the records we made. I love everything we did. I wouldn’t change a thing.

DeMARTINI: I don’t think so. I mean, all you can do is the best you can do at the time. And that was what made it happen for Ratt to begin with. There was no manual or map or anything like that. It was just instinctual. I totally trust that instinct and always did.

LYNCH: Probably the same thing all bands from that era might wish: that we wore outfits we wouldn’t regret; that we didn’t have so much reverb on the mix. Lifestyle choices. Image choices. But I guess if there’s one thing… I wish the band had not called itself Dokken. [laughs] I think that was unfair, and I think that’s what ultimately led to the demise of the original version of the band.

BETTENCOURT: I think the only thing would have been to take a breather. Because we kept going and going, and by the time of [1995’s] Waiting for the Punchline we were burned out. I think it affected our music and affected the way we were doing things.

COLLEN: No, because we got to this point where we are now. We’ve just done a hugely successful stadium tour with Journey, with the two bands flip-flopping as headliners, and it was just about all sold-out. We had some struggles earlier on in our career, but I think everything we did was kind of right.

Looking at old photos is usually a cringe-inducing experience. Do you look back at photos of yourself back in the day and go, “What was I thinking?”

DeMARTINI: No, not personally. But there’s definitely things that other people wore!

FORD: I did dumb stuff — wearing shirts you could see through and all that. But I can’t look back with regrets. You do dumb stuff when you’re young — that’s my excuse.

COLLEN: Well, for me, it was even worse before Def Leppard, when I was in Girl. We’d done some TV and some of the crew got hold of a video, and we’re in makeup and all this stuff… it was hilarious. But I think you look back at it lovingly.

LYNCH: The thing is, we thought it was so cool. It was androgynous. It was sexy. I mean, there couldn’t have been anything better in our minds. It was like, “What are people gonna do in the future? How are they gonna top this?” It’s not possible! [laughs]

BEACH: I love my old pictures. I look at that stuff and go, “Look at how young and gorgeous I am!” I love the clothes and the hair. I look at that stuff very fondly, and I’m not ashamed of it all. I wish it were still happening. Please, somebody, can we bring hair metal back?

Rich is the co-author of the best-selling Nöthin' But a Good Time: The Uncensored History of the '80s Hard Rock Explosion. He is also a recording and performing musician, and a former editor of Guitar World magazine and executive editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine. He has authored several additional books, among them Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck, the companion to the documentary of the same name.