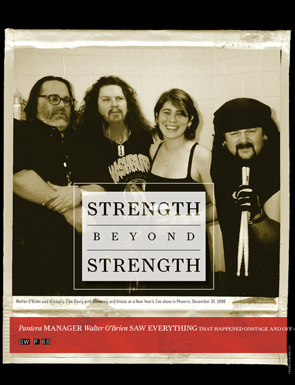

Walter O'Brien: Strength Beyond Strength

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Originally published in Guitar World, January 2010

Pantera manager Walter O’Brien saw everything that happened onstage and off—and lived to tell the tales, including the story of the drama and drugs that led to the group’s demise.

Few people in the music industry worked with Dimebag Darrell and Pantera as closely, and for as long, as Walter O’Brien. As the president of Concrete Management, O’Brien served as Pantera’s day-to-day manager from 1989 until 2003. He accompanied the band in the studio and on the road for much of their career, and was instrumental in helping to make them one of the biggest heavy metal acts of the Nineties.

O’Brien, who earlier in his career had worked with such acts as Genesis and Peter Gabriel, cofounded Concrete Management and Marketing with Bob Chiappardi in 1984. In 1991 the company split, and O’Brien took over operations for what became known as Concrete Management. Over the years, his organization guided the careers of such superstar metal acts as Anthrax, White Zombie and Ministry, though no relationship lasted as long, or arguably reached such heights, as the one Concrete forged with Pantera.

In 2003, O’Brien ceased formal activities as Concrete Management and shut down the company’s offices. He has since retired from the music business and turned instead to focus on freelance writing and photography. In this exclusive interview, he looks back on his time with the band and tells the story of their tremendous rise and tragic fall. He also discusses how he came to sign Pantera, who he says he initially thought were “terrible,” and recalls some of his highest, and lowest, moments with the band, from celebrating Number One albums, to witnessing drug overdoses, to attempting to navigate them through their tumultuous final years. As a manager and a friend who was with the band every step of the way, he sums up his time with Pantera thusly: “It was a lot of headaches, and a lot of hard work. But it was also the best 14 years of my life.”

GUITAR WORLD How did you come to manage Pantera?

WALTER O’BRIEN It’s actually a funny story. When the band was putting those first few independent records out, pre–Phil Anselmo, they would send me copies and ask me to manage them. And I would always say no, because basically the records were terrible. The band was very glam, and they were in spandex, and I just didn’t think that much of it. Obviously, Dimebag was a great guitar player, Vinnie was a great drummer and Rex was a great bass player, but the frontman at the time [Terry Glaze] just didn’t do it, and the songs just didn’t do it. Power Metal [Pantera’s first record with Phil Anselmo, released in 1988] was a little better, but they still had the yellow spandex and stuff, and it wasn’t my cup of tea.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Now, around 1989 I was working to get one of my other bands, Metal Church, a new record deal, and I went to see a friend, Derek Shulman [then president of Atco Records] to see if he was interested in signing them. Derek said, “I don’t really want to sign a band that’s been around the block a few times. But I do have this new group I’d love to have you manage—Pantera, from down in Texas.” And I went, “Oh, no, no, no. I’ve heard their tapes!”

GW So then what happened?

O’BRIEN Mark Ross, who worked in A&R at Atco, asked me to go down to Dallas with him to see the band play. He said, “You gotta see them live.” So I thought, What the hell, I’ll go. If nothing else, I’ll get a nice dinner out of it! We went to see them at Dallas City Limits, a bar with pool tables. And the place was jam-packed—there were probably a thousand people there. All completely nuts. It was an unbelievable scene. Pantera hit the stage and it was total pandemonium. I’d never seen anything like it. Dimebag and Rex were flying all over the stage, Phil was taking leaps off the drum kit, Vinnie had the unbelievably fast double-kick going. By the second song I said to Mark, “I’ll do anything to manage these guys.”

GW What was your first meeting with the band like?

O’BRIEN I went backstage after that show and begged them to let me be their manager. And they all said, “Well, we thought that’s why you were here!” And that was it.

GW You were in the studio with them during the recording of their major-label debut, Cowboys from Hell.

O’BRIEN I was there for a lot of it. I didn’t have a role in the making of it, but I would go down and sit around and watch while they were recording. And I remember at one point there was talk that they didn’t want to include the song [“Cowboys from Hell”] on the album. And Mark [Ross] and I were like, “You gotta be kidding. That’s the title. That’s the whole thing! That’s gonna be your nickname for the rest of your lives. It’s perfect.”

GWCowboys from Hell signaled a massive change in direction from Pantera’s earlier glam-metal records. What do you think sparked such a drastic leap?

O’BRIEN It was definitely a lot of Phil’s influence. I wasn’t there for the recording of the album before it [Power Metal], but as far as I know that record was conceived pre–Phil Anselmo. It was written with the old singer in mind. So that album was still the old Pantera. And of course, prior to Pantera, Phil had been in a bunch of glam bands too, so he had that same background as the other guys. But after Power Metal he started coming into his own and getting into the whole hardcore scene. And the other guys dug what he was into. Then, when Phil became a creative part of the band in terms of writing, that pushed it over the top, and you got Cowboys.

GW Is it your belief that had Phil Anselmo not joined Pantera they would have been a very different band?

O’BRIEN Absolutely. I think they might have gone heavier, but Pantera would have never happened the way it did.

GW The way it did happen was that Pantera became the biggest metal band of the Nineties. Was it clear to you when that shift occurred?

O’BRIEN Absolutely. I think it started when Vulgar Display of Power was released [in 1992]. Cowboys had been just a big long slog of a tour. We kept the band on the road a long time, and toured that record to death. Then Vulgar came out, and in my opinion it was a much better album, much closer album to the classic Pantera thing, and we just did the same thing with that. We toured and toured and toured.

By the time they went in the studio for [1994’s] Far Beyond Driven, we knew something big was brewing, and we pulled out all the stops. And the record label was really behind us. We got the head of the label to secure us the Time Warner Gulfstream jet for the week of the album’s release, and we did 10 in-stores in seven days, cross-country, hitting every major market. Then we got MTV involved. We brought Riki Rachtman [then host of the MTV’s heavy metal show Headbangers Ball] onboard the jet, along with a Headbangers Ball contest winner, and they covered the whole thing. At the same time, we put tickets on sale for the tour and had a video [for “I’m Broken”] in rotation on MTV. So everything was in place for a big release week. And Far Beyond Driven came out and debuted at Number One. First metal album in history to do it. That was it. That was the peak.

GW And yet, things had already begun to crack internally. During the recording of the next album, 1996’s The Great Southern Trendkill, Phil refused to come into the studio.

O’BRIEN Phil was always a loner, but when it came to recording the albums and stuff like that, everybody hung out mostly together, and he played his part. But yeah, Trendkill was when things started to change. I actually had to fly to New Orleans with Dimebag and [producer] Terry Date to have Phil record his vocals. He wouldn’t come to the studio in Texas. He didn’t want to. He was just trying to show his strength, I guess.

GW Did Dimebag and the others show concern about what was happening?

O’BRIEN We were all concerned. Dimebag definitely. Vinnie was very upset. Rex wasn’t thrilled either. And Dime being the big creative guy along with Phil, they were starting to butt heads. I should be careful how I word this, because I don’t want to overstate something in the wrong direction: It’s my opinion that Dime, Vinnie and Rex would have been very happy to be the next Van Halen or Metallica. They wanted to be the big arena rock band. Phil got to a point where he started to sort of back up. He wanted to be back playing in the bars, doing hardcore stuff that would scare your parents. He was into death metal and black metal, and he wanted to take Pantera in that direction. And as management we kept trying to say, “Look, you can make as many solo albums as you want, but Pantera is already an arena rock band. And with just a little twist you’re going to go triple Platinum with the next record.” And that’s not selling out—it would have still been Pantera. But he just kept pushing it.

GW The records did get progressively heavier. Do you think those last few Pantera albums were the ones Dime and Vinnie wanted to make, or would they have preferred the sound to have been a little different?

O’BRIEN I don’t really want to speak for them, especially Dime, since of course he can’t confirm or deny anything. But… yeah, I would say that’s pretty close to true. They liked the heaviness, don’t get me wrong; they loved making heavy records. But Dime had a different sense about the lyrics. In my opinion he thought the lyrics were getting to be a little too much. Songs like “Good Friends and a Bottle of Pills” [from Far Beyond Driven]…stuff like that. It got a little better with [2000’s] Reinventing the Steel. But by then there was such a big chasm in the group.

GW Common consensus is that the beginning of the end came when Phil suffered a heroin overdose backstage at a show in Dallas in 1996. Were you there that night?

O’BRIEN I was. That was a very bad day. I had always told the guys that I would not deal with a band that got involved with heroin. And I knew that meant there were bands I could never be involved with because they were junkies. But at the time, none of us knew Phil was using. We were all sitting backstage in the Pantera dressing room, partying, having a great time. It was a killer show, a big, big venue in Dallas. It was a homecoming. Everybody was there—family, friends. And all of a sudden somebody came in, screaming, “Phil’s dying! Phil’s dying!” We all jumped up and ran down to the room where Phil was, and he was laying out on a couch or a table or something, so dark blue you couldn’t even see his tattoos. And he’d stopped breathing.

So an ambulance came and they ran him off to the hospital. And the Pantera guys said to me, “You gotta go to the hospital.” And I said, “I ain’t going to the hospital. I am not chasing junkies all over town. I’m sorry. And if that means you’re firing me, fine. I’m probably quitting anyway.” And I remember as soon as I walked away, I saw all his New Orleans jackass friends, from Eyehategod and a couple other bands, who are all junkies and morons and losers. And one of them, a guy who was in Down [drummer Jimmy Bower], came up to me and said “Cha-ching! What’s the matter? Your big payday get taken away from you?” I said, “What the fuck are you talking about?” And he said, “Well, you’re the one that let this happen.” And I said to him, “You’re the jackasses that do this shit around him and tell him it’s okay. And as far as a paycheck, I just quit.”

GW But you didn’t quit.

O’BRIEN I didn’t. Really, I couldn’t leave. So the next morning we had a big band meeting. We all went in a room and basically called Phil out on a lot of things. But he just wasn’t owning up to it. So that was the beginning of the end.

GW Once the split occurred, a war of words began to play out in the media. Behind the scenes, how close was the band to getting back together?

O’BRIEN Well, the strange part is that they never really split. After Reinventing the Steel came out, they went overseas for a European tour, and 9/11 happened. The band was stuck in Dublin, and they cancelled the tour. They said, “We don’t want to be a very obvious American band driving around Europe in a bus right now.” About a week later we got them back to the States, and that was pretty much it. They never toured again.

But the three guys were always gung-ho to get going. They were ready to go into the studio the day they got back from Ireland. Dime was writing songs, Vinnie started writing songs, even Rex started doing stuff. We just could not get them together. Phil moved out to the country in Louisiana, and he wouldn’t answer his phone. We would have to contact his friends in New Orleans, and they would have to drive an hour into the country just to pass a message along. We tried every way to get them together but couldn’t do it. And this went on for a very long time. Eventually the guys said, “We don’t think Phil is ever going to come around.” And they started working on Damageplan. And that was it. I never talked to Phil again. And to this day nobody has ever told me that he quit Pantera.

GW Is it your belief that there would have been another Pantera record one day?

O’BRIEN Yeah, I really have to believe so. I know the three guys were always dying to do it again. And I know they were always ready to forgive Phil. And from what I was hearing from Phil’s friends, he was starting to come around too. But then, needless to say, Dime was murdered, and that put an end to that idea.

GW Publicly, Dimebag was such a gregarious, fun-loving personality. As someone who knew him very personally, was there a side of him that the world at large wasn’t privy to? A “private Dime”?

O’BRIEN To be honest, no, there wasn’t. He was pretty much exactly the same guy behind closed doors. It was genuine. I mean, maybe once in a while he could be a mean drunk, but that was generally only when the security guards were trying to throw him out of a casino. [laughs]

GW Do you have any particular fond memories of him that stand out?

O’BRIEN Actually, one of my favorite memories of Dime—and it happened dozens of times—was when it’d be six in the morning, we’d be at the eighth casino of the night, Dimebag couldn’t be more drunk, and about eight security guards would have us circled and would be walking us to the front door. It was like border collies and sheep. And every single time, at the very last second, Dime would break from the pack and run back and throw himself at the blackjack table, scaring the shit out of everybody sitting there. He’d drop $500 in chips and double down on, like, threes, or something really ridiculous. And he’d lose the $500. And then the security guys would come back, grab him and march him out the front door. And the whole time he’d be yelling at the top of his lungs: “Ya done took aawwl mah money! I just wanna stay here and have some fun!” He’d yell that over and over. He just wanted to have a good time. That was Dime.