ZZ Top Interview: Double Back

With Recycler, ZZ Top looked to the future by going back to their roots. Billy Gibbons and Dusty Hill recall how it felt to boogie again.

Once upon a time there was William Bunch, bluesman. The said Bunch wasn’t a bad guitarist, and he was a pretty good pianist. But he had a great imagination. So one day he began calling himself Peetie Wheatstraw, the Devil’s Son-In- Law and High Sheriff from Hell. And Peetie did pretty good for himself.

William Bunch understood that the blues is more than music. It is entertainment. Even more so, it is mysterious.

Tommy Johnson, like the more famous Robert, was said to have sold his soul to the devil in exchange for his skills on the guitar. According to blues scholars, Tommy did little to discourage such talk. Like William Bunch, he understood the power of mystery. Consider Charlie Patton, known as the Father of the Delta Blues, and Aaron “T-Bone” Walker, perhaps the greatest guitarist to come out of Texas. Their styles couldn’t have been more dissimilar, but they had at least one thing in common: they were energetic entertainers who, long before Jimi Hendrix restrung his first Strat, played guitar over their heads and behind their backs.

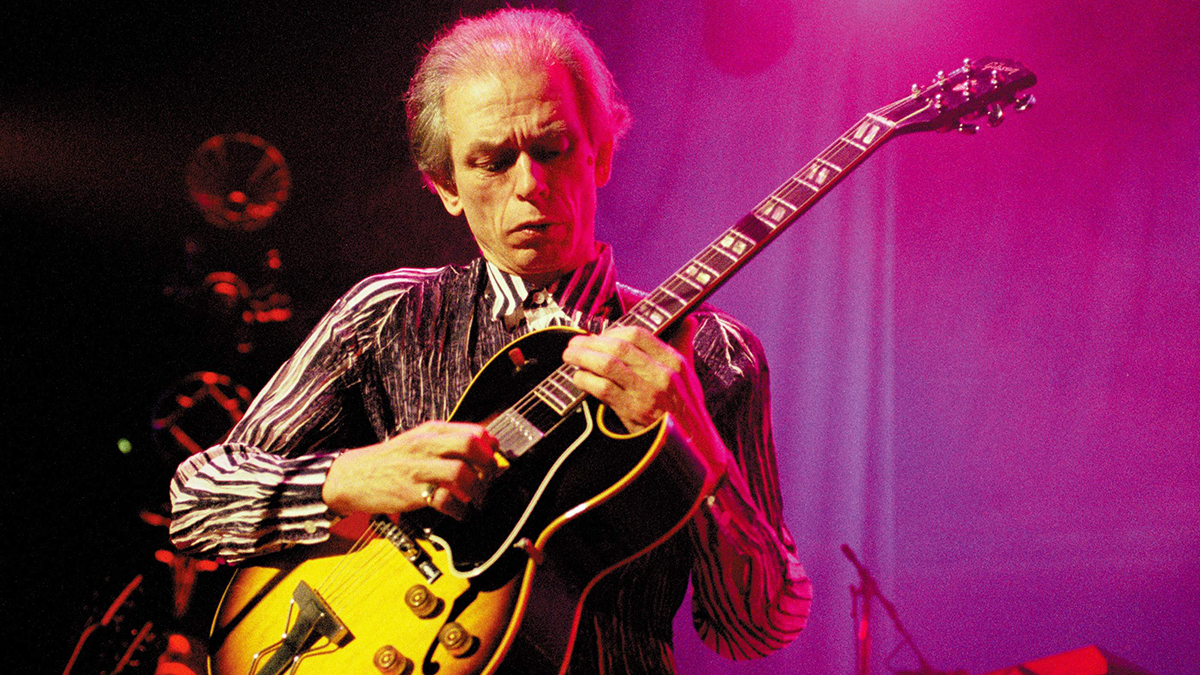

Billy Gibbons and Dusty Hill understand the blues. “Understand,” as the word is used here, is not meant in the historic or musical senses, though the two are certainly well equipped in those arenas. As a child, Billy spent countless hours in the time-honored pursuit of Listening to Music You’re Not Supposed To. Today, in the true tradition of the blues obsessive, his eyes light up in intimate recognition at the mere mention of an obscure Delta guitarist. And Dusty Hill? He was playing bass behind the legendary Freddie King at 15—an age when most kids think a “shuffle” is something lazy people do.

Nevertheless, Gibbons and Hill understand the blues in a manner that transcends their considerable knowledge of the music’s development and instrumental techniques. Unlike so many second-rate, would-be blues players, they share an intuitive feel for the blues on an entirely different level.

Perhaps the best indicators of this sensibility in Billy and Dusty were the great videos from the Eliminator album—particularly “Sharp Dressed Man” and “Legs.” Gibbons, Hill and drummer Frank Beard were nothing less than genii in those clips, benign, intangible figures who existed solely to spread thumbs-up encouragement and hot-babe good cheer to deserving, overworked souls worldwide. The ZZ Top boys are the least-focused personas in the videos—the most mysterious. The beards further blur their identities. Gibbons and Hill are not Amish farmers. Nor are they 19th century prospectors, or Hasidic Jews. They are a bit like Peetie Wheatstraw, the Devil’s Son-In-Law and High Sheriff from Hell. ZZ Top and William Bunch would understand each other—that much was made clear by the group’s 1991 album, Recycler. While it was by no means an acoustic blues album, it was the rootsiest thing Gibbons, Hill and Beard had done in years, the work of men who know the blues—the entertainment, the mystery. As Billy himself sang, “My Head’s in Mississippi”…

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

GUITAR WORLD What is it about the blues that attracted you?

BILLY GIBBONS The backbeat. The two and the four made your head snap. Plus it was cool because our parents hated it. [laughs]

DUSTY HILL Actually, my mother turned me on to the blues. We had Lightnin’ Hopkins as well as Elvis Presley records. I thought everyone had them. I’d go over to friends’ houses and ask them to put on some Howlin’ Wolf, and they wouldn’t know what I was talking about. Then, when they would come over to my house, I’d play them some blues. Their parents wouldn’t let them come back. [laughs] The blues were still called “race records” back then. I mean, how cold is that? The emotion on those records really captured me. I loved the feeling of the music. When I started playing, I couldn’t wait to play something that had that much feeling.

GW In what way did the blues stimulate your imagination?

HILL When I was younger, I’d listen to a song and take it literally. I’d think, Boy, what a drag. How horrible, he must be really bummin’. If it was about sex I’d think, Boy, I wish I was that guy!

GW Because your appearances are so unusual, and your videos are so clever, it’s very easy to believe that ZZ Top live the lyrics to their songs. In that way, the band comes close to capturing the essence of those legendary country bluesman.

GIBBONS You’re right. Cotton is no longer picked by hand, so the problem is: How do you go about writing fresh blues? The blues deals with the highest of highs, the lowest of lows and all points in between. So we had to create surrealistic entities that could handle those extreme mood swings. It seemed that this was the only legitimate way to approach it. We like to think of ourselves as the Salvador Dalis of the Delta.

GW The ZZ Top phenomenon is a wonderful vehicle for fantasy. Do the fans ever confuse your real selves with your video and vinyl personae?

HILL Oh yeah, especially when I’m at home! For example, I’ll go into a convenience store, and invariably the guy behind the counter will say, “What are you doing here?”— like he doesn’t believe I eat, or something! Then once that’s out of the way, he’ll start looking out the window to see if the car and the three girls are out there. I usually end up telling him that the girls are repairing the car back at the house, so he won’t be too bummed.

GW Billy, you’ve mentioned that Bo Diddley was one of your big influences. Like you, he was known for his odd-shaped guitars, great rhythm chops and unusual stage clothing.

GIBBONS He was the perfect bridge between Delta blues and rockers like Chuck Berry. Bo’s tone—which was produced by a custom Gretsch guitar and two DeArmond single-coil pickups set in the middle toggle position, and a Magnatone amp—was dramatically different. He didn’t sound like anyone else. His sound, combined with his array of bizarre rectangular guitars, made him a real hero. The fact that a major manufacturer built him a special guitar also intrigued me. I thought, Who is this guy? How did he get Gretsch to make him a guitar? He’s still one of the most fascinating figures in American rock and roll. Interestingly, his sound seems to be making a comeback. Recently I’ve heard a couple of records featuring his distinct rhythm tone. I guess it’s taken the music world 30 years to finally crack the code. [laughs] It’s still a fine sound.

GW Who else influenced your sound?

GIBBONS Dusty and I recently compared notes on that subject and came up with the obvious: B.B. King, Muddy Waters, Jimmy Reed, Howlin’ Wolf, John Lee Hooker and Albert Collins. But some of the more obscure influences include Terry Simpson, who played with a Texas outfit called the Raiders. They had several instrumental hits in the Sixties, including “Stick Shift,” “Motivation” and “Raising Cain.” The Nightcaps, out of Dallas, were also big influences.

HILL Every once in a while, Billy will throw a Nightcaps lick in the middle of a song during a live show, and we’ll just look at each other and wink. I love it when he does that, ’cause it usually doesn’t belong there. My major influences were primarily guitar players and bands; I started playing bass by accident. My older brother played guitar and I sang. We found a drummer and soon realized we needed to complete the rhythm section, so they elected me to be the bass player. Straight away we were playing in clubs and jamming with everybody in town, so I really learned to play while onstage. After playing for two years, I landed a gig with Freddie King! I was amazed that they even let me on the same stage, because I really wasn’t very good—though I came pretty cheap. [laughs] I was only 16 at the time and was petrified. Back then, the clubs were still segregated. One night we played the Ascot Ballroom, which was a black club. I didn’t have a driver’s license at the time, so somebody dropped me off. I rolled my stuff up to the door, and the doorman, who was a pretty big fella, said somewhat threateningly, “What do you want?” I said, “I’m with the band.” He looked me over and said, “I don’t think so.” Just as all these people started gathering around, Freddie pushed his way through the crowd and said quietly, “C’mon.” After one song, everything was all right.

GW What gear did you use when you were playing with Freddie King?

HILL I was playing an old hollowbody Harmony through whatever I could borrow. I finally stepped up to an Ampeg, which I loved because it had rollers!

GIBBONS Love that outboard gear. [laughs]

GW Was Freddie your main influence?

HILL I learned how to play primarily from Freddie, my brother and Billy. Interestingly, all three share the same philosophy: “Less is best.” And “Solid less is the best.” If you have a solid foundation, then you can play.

GW Why is Dallas such a holy place for guitar?

GIBBONS Culturally, up until the mid Fifties there wasn’t much to do except play.

GW Dusty, who influenced your singing?

HILL Initially, Elvis and Little Richard. Then there was a long gap. I’m not knocking Pat Boone and Bobby Vee and all that stuff, but it was really getting boring. Then came the English guys, who really saved me. I think people like the Beatles lifted everyone back up.

GW Beginning with Eliminator, ZZ Top’s whole production style changed. The primary difference can be heard in the rhythm section. Where many groups sweetened their sound by adding synthesized strings and bell tones, you took the opposite route by doubling bass lines with fat, analog-style synths. At times, those doubled bass lines were supplemented with additional sixteenth-note bass ostinatos. How did that approach evolve, and how did you feel about that as a bass player?

HILL I felt fine about it. I have no problems with anything that will enhance the sound. I consider the synthesizer to be just another instrument. I know some people have a problem with it, but eventually they’ll get used to it. In the early days, they wouldn’t let a drummer play in the Grand Ole Opry. Now it’s accepted.

GW I wasn’t trying to suggest that the synthesizers had a negative impact on the songs. I was just wondering how the production style evolved.

GIBBONS We had recorded El Loco and Deguello with everyone in separate booths, and we hated it. It felt too sterile. It really bothered us to be connected with headphones and microphones. So at the outset of Eliminator we decided to record in a circle, as a band unit, in one room. Out of that group focus came a new attention to tempo. We started playing to click tracks, drum machines and sequencers for added precision and found that we enjoyed it. It also had a positive impact on tightening up our playing. If you’ll notice, the timing on Eliminator is tighter than on our previous records. We started adhering to a strident observance of tempo. ZZ Top becomes a fourpiece band when “Mr. Time” arrives.

HILL When the rhythm section is rock solid, Billy can be any place he wants to be. That’s where the sequencing came in. It’s a strange but effective combination. Playing in the same room allows us to reap the full benefits of that “human feel.” At the same time, we’re able to juxtapose that rootsy groove on top of machine-generated rhythms. The approach allows us to combine the best of both worlds.

GIBBONS It wasn’t really that calculated, because we really didn’t know what we were doing in the synthesizer domain—which made it more fun. We took our cue from Frank Zappa, who said, “Don’t read the manual; just get your hands dirty and do it.”

GW How did Recycler come together?

GIBBONSRecycler was interesting to make, because initially we planned to follow the lineage established in Eliminator and Afterburner. We had written a couple of highly structured pop tunes in our studio in Houston. Then we went out to Los Angeles for a couple of months and got into the whole sequencer, everything-in-its-place thing. But when we arrived in Memphis to finish the record, we slid into a different mode. While we were waiting for all of our high-tech gear to arrive, we set up in a circle and started playing and jamming as a band. The sound, even though it was rougher and looser, felt right in every way. The results of some of those sessions can be heard on cuts like “2000 Blues” and “My Head’s in Mississippi.” Both are reminiscent of our earlier music, which is why we call Recycler our Tres Hombres/Eliminator album.

We didn’t abandon the ground we covered on Eliminator and Afterburner—you can still hear the sequencers and synthesizers—but they’re much more unobtrusive. We allowed some of the rougher elements of the band to come shining through. “My Head’s in Mississippi,” which was one of the first completed tracks on the album, is a great example of how we mixed the new with the old. Initially, it was a straight-ahead boogie-woogie. Then Frank stepped in and threw in those highly gated electronic drum fills, which modernized the track.

GW How long did it take for you to complete the album?

GIBBONS Not counting the preproduction time in Houston and Los Angeles, it took us four months to make. Recycler was one of our longer projects. I think it took extra time because we moved to Memphis Sound studios on Beale Street. That area is chock full of distractions. There were a lot of great characters always hanging out on the streets. There was one street musician named Alabama, who knew only one song: “Baby Please Don’t Go.” But that’s all he needed to know. He’d play it for one crowd, and when they would move on, he’d play it again for the next crowd, and so on.

GW Billy, your tone is instantly recognizable. What does it consist of?

GIBBONS Tone goes hand-in-hand with delivery, and I credit our producer Bill Ham for coaching me on where the notes should fall. You can really thicken the guitar track by laying back just a breath from the downbeat. That way, the guitar isn’t competing directly with the bass and bass drum for space. It’s surprising how much that little trick can add to a track.

Also, it’s hard not to get a great sound nowadays, with all the wonderful equipment on the market. I’m particularly impressed with Tube Work’s MosValve amp. It’s just the wildest thing. We used the MosValve and our usual assortment of Fenders and Marshalls.

GW Billy, you and Dusty were close friends and musical colleagues of Stevie Ray Vaughan. It would be appropriate if you concluded our conversation with some words of reminiscence.

GIBBONS He was a tremendous player and a tremendous person. There was a real beautiful sense of closure at Stevie Ray’s memorial service. We talked a lot about the old days. One thing particular stood out in my mind: I remember playing a private dance club in Dallas called Arthur’s. Stevie Ray, who was 16 at the time, asked to sit in. His older brother, Jimmie, was sitting on the sidelines, so I kind of looked over at him and he just shrugged his shoulders; he didn’t say a word. So I let Stevie jump onstage with his red SG. He plugged in and just started wailing. I looked over at Jimmie, who was grinning with a look on his face that said, “Yeah, he my little brother.” He was so proud.

I think his duet album with Jimmie [1990’s Family Style] is a real gift. We all feel so fortunate to have that kind of playing survive in the face of such a great loss. I don’t think anyone should harbor any long-term sadness, though. You must grieve the loss to the fullest, but I think he graced us with a great memory and a sense of purpose.