“We didn’t have musical training. Brian and I took music classes, but I think he dropped out, and I got an F”: The Beach Boys guitarist Al Jardine on the genius of Brian Wilson, working with the Wrecking Crew and touring with Jeff Beck

In this 2015 interview, Beach Boys guitarist Al Jardine recounts some of the pivotal moments as a key member of one of America’s greatest musical treasures

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Six decades ago, the Beach Boys’ Help Me, Rhonda, a Brian Wilson/Mike Love composition sung by Al Jardine, helped itself to the top spot on the U.S. singles charts.

It proved that an American band could hold its own during the height of the British Invasion.

The hit single was actually a re-recording of the song, which started its life as an unassuming album track from 1965’s The Beach Boys Today!

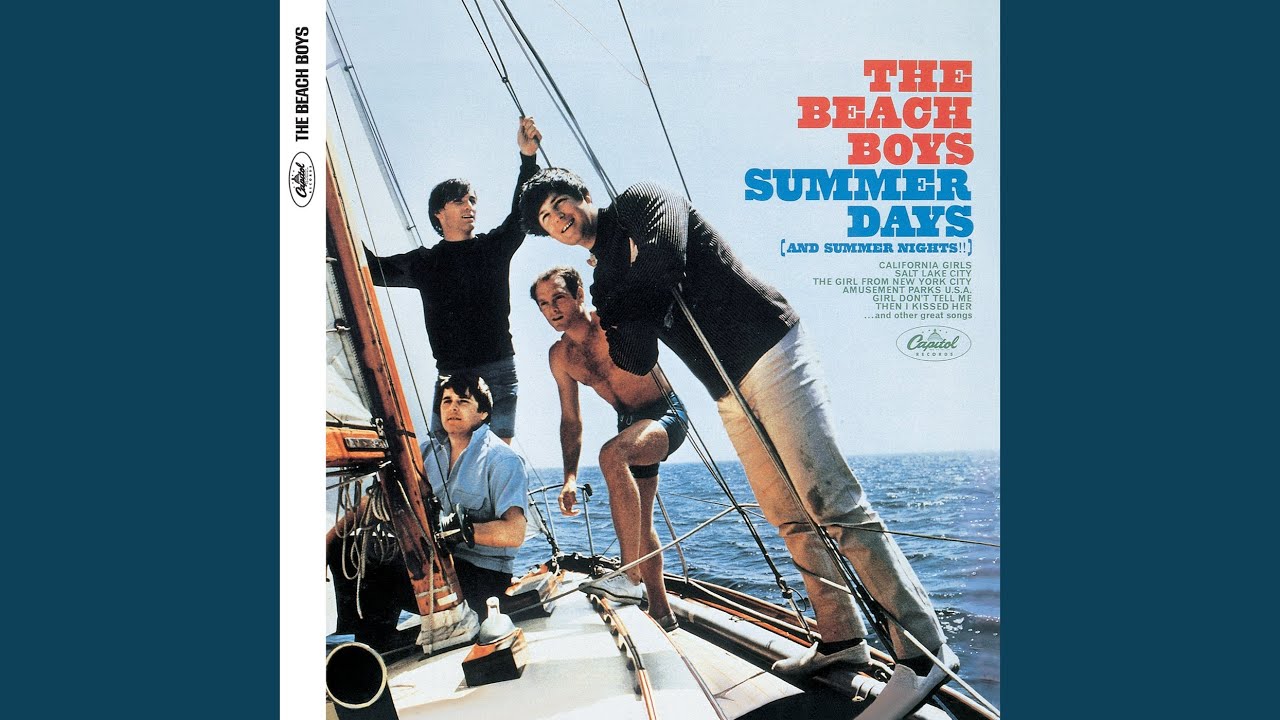

Disc jockeys suddenly started playing it, so Wilson, the band’s multi-tasking leader and producer, re-arranged the song for radio and organized a new recording session – and a hit was born. The single version appeared on the band’s second 1965 album (they released three that year), Summer Days (and Summer Nights!!).

Today! and Summer Days were landmark albums for Wilson and the Beach Boys. The songs’ increasing lyrical depth and Wilson’s sophisticated orchestral ‘Wall of Sound’ approach to production – achieved through the use of a team of L.A. session musicians unofficially known as ‘The Wrecking Crew’ – laid the groundwork for his undisputed masterpiece, 1966’s Pet Sounds.

When viewed as a group, these three albums show Wilson at the apex of his creative powers – completely deserving of the “visionary” crown he wore – off and on – for the next 50 years.

In 2015, 50 summers after Summer Days, Wilson and Jardine – who shared six-string duties with lead guitarist Carl Wilson until Carl’s death in 1998 – hooked up for Brian Wilson’s No Pier Pressure Tour, a U.S. trek that also featured former Beach Boys guitarist Blondie Chapman.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

In addition, Jardine and Chaplin appeared on Wilson’s studio album, No Pier Pressure, which was released in April of that year through Capitol Records, the Beach Boys’ original label. The album also featured guitar work by David Marks, another occasional Beach Boy.

With all this Beach Boys mojo in the air, in 2015 Guitar World invited Jardine to chime in on some of the good, bad and ugly moments in the Beach Boys’ long, storied and sometimes bizarre history.

Incidentally, the then-72-year-old Jardine was still singing Help Me, Rhonda in the original key.

It’s become common knowledge that many of the instruments on the Beach Boys’ mid-’60s albums were played by session musicians, including a gang of L.A. pros later known as the Wrecking Crew. Did that ever bother you – not always playing guitar on your band’s albums?

“Oh, no, no, no. [laughs] I could go clean the pool, [drummer] Dennis [Wilson] could go surfing. Dennis was the first one to bolt. He was such an outdoor guy – he just liked being out with his cars and boats, surfing and all that. He was thrilled to be able to take some time off. [Wrecking Crew drummer] Hal Blaine and those guys were so good, so it allowed the music to go to another level.

“You have to remember, we were always gone, always out touring, and we were beat to hell when we got home. And then Brian, who stayed back and worked on the albums in the studio, would be calling us in to do vocals, which was a project in itself. Brian didn’t sleep. He was so impatient for us to be home. But I think Carl attended most of those sessions because he was Brian’s Number One go-to guy.”

When you listen to the outtakes from the Good Vibrations recording sessions, Brian can be heard directing the musicians, very much the man in charge. Was it like that as soon as he started producing, even on 1963’s Little Deuce Coupe and early 1964’s Shut Down Volume 2?

“Pretty much, yeah. It was his vision. He was hearing the pattern, the melodies. He knew what he wanted, and that was great. It’s wonderful to have that energy, to have someone in charge. Otherwise, it would be a train wreck. Later on I played bass on a couple of the albums, so it gave Brian the opportunity to be behind the window in the control room.

Brian and Carl could sit in the control room... plug directly into the console and work on a riff. That’s why the purity is so beautiful on California Girls – it’s so grand and clean, just straight to tape, no extra cables, pure signal

“It must’ve been wonderful for him; otherwise he’d have to go back and forth between the studio and the control room. He usually had a little chart made up for us each day. I was impressed with his ability to impart that to the rest of us, even though we didn’t have musical training. Brian and I took music classes, but I think he dropped out, and I got an F. [laughs]”

Did Brian’s vision extend to Carl’s guitar solos?

“No, Carl gave that part to the band. He made up the solos. I was always the rhythm guitarist because I never had any guitar training. I just became the anchor behind that.

“Brian would go to Carl because they lived together for a long time; he’d come to Carl first with an idea. He might sketch it out on the keys, like with California Girls. I think he told Carl what to play on that one. That was a beautiful session.

“They had such a great rapport, being brothers. Carl would do anything for him. They could sit in the control room all nice and peaceful and quiet, while the whole damn band was out on the floor, plug directly into the console and work on an intro or riff.

“And then there’s no bleed in from the other instruments because you’re going direct. That’s why the purity is so beautiful on California Girls in particular. That’s one of my favorite intros of all time. It’s so grand and clean, just straight to tape, no extra cables, pure signal.”

How would you describe or rate Carl as a guitarist?

“He, like the rest of us, just grew up with this thing, so we weren’t technically very good. But he had exceptional talent, just like his older brother. He had something special about his ear. He had an ear for pitch and alacrity on the fretboard.

“He wasn’t Jimi Hendrix, but he could play in structured areas. We made songs more as two- or three-minute statements like vignettes, and every eight bars had a reason. It wasn’t like the Grateful Dead. [laughs] It was our mission to make great hit records…and it was fun.”

In terms of gear, do you still have any of your ’60s-era Beach Boys guitars or basses?

We kept losing guitars because we toured so much. They’d get stolen right off the back of the truck

“The problem is we kept losing them because we toured so much. They’d get stolen right off the back of the truck. We could never keep them in stock. We’d just have to get new ones, so I don’t have a clue where they are. So through the ’60s we’d just keep recycling them.

“I have a couple of replica Strats that play almost as good as the originals, or as the one I was playing in the ’80s, which is in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. I think I’m gonna ask for it back so I can go out and play it. It’s nice to look at, but it should be played.”

Did you ever attend the Wrecking Crew Beach Boys sessions and mingle or confer with those legendary session guitarists, including Glen Campbell, Tommy Tedesco or Barney Kessel?

“Oh god, yeah. Glen even came out on the road with us for about six months. I was able to work up a real great friendship with him and help him out onstage because he wasn’t used to playing out on the road.

“He replaced Brian [in the touring band] in late 1964. He was going to have to sing Brian’s high parts and play the bass. He’s primarily a guitar player, so I offered to play the bass so he could concentrate on the high parts. That was a lot to ask of him. It was very sudden, just a couple of days’ notice.

“But yeah, I did meet all the guys and I did attend some tracking sessions. I couldn’t tell you which ones; there were so many. By the way, someone told me Hal Blaine considers me the best rhythm guitarist. I said, “Is he crazy?” [laughs] There are so many better players than me. But there’s a trick to good rhythm guitar, so I take that as high praise.”

Of course, even if you didn’t always play guitar or bass on a bulk of those mid-’60s sessions, you’d still have to learn the parts for when you toured behind a new album. Was Brian involved in helping you come up with those live arrangements?

“Oh, yeah. He actually came out on the road with us when we first performed Good Vibrations, and it sounded pretty damn good! That was one we were particularly concerned about. We had to have a Theremin made up, a little slide Theremin, a piece of wood with a ribbon on it, which made a real good sound. So we got that one down in its essential parts.

“What I’ve found is that all these songs were so well written that it really doesn’t matter if you have all the instruments. It’s wonderful if you can, and in this particular iteration of Brian’s band [on Wilson’s 2015 No Pier Pressure Tour], every part is on there, every instrument is being replicated.

“But in those days we had only five pieces, five guys singing and playing, but it still sounded good. It’s really all about the melody. If the melodies and harmonies are there, you can have a ukulele in the background.”

After the cancellation of the doomed Smile album in 1967, Brian started to check out as the band’s sole producer. He struggled with drugs and even checked into a psychiatric hospital. How did the band take it, and how did you guys manage to take over the reins so smoothly?

“It was just necessary. He was checking out. He wasn’t always there, so we had to pick up the slack. So that’s when we started to contribute more as a band. I think it was remarkable what we came up with, looking back on it. It wasn’t commercial at the time, but it certainly has had an impact.

Decades later, people were starting to appreciate what Dennis and Carl came up with... We encouraged Brian to stay involved, but mental illness has a way of having its own way

“Decades later, people were starting to appreciate what Dennis and Carl came up with – and me, for that matter. It really goes to show you what we can do when the chips are down. We encouraged Brian to stay involved, but mental illness has a way of having its own way.

“It’s amazing that we’re back again today doing this. It’s an amazing feat that he’s so accessible and capable of delivering the music with this great band. And we’re having a good time doing it! We should, we deserve it. Damn right, man, after all we’ve been through.”

After the “Wall of Sound”/Wrecking Crew era, when all the Beach Boys took a more hands-on approach to tracking and producing, did you guys ever feel drawn to the sort of thing Jimi Hendrix and Led Zeppelin were doing? Did you want to go out and get some Marshall stacks? And, while I’m at it, did you ever meet Hendrix?

“No, I never met him. And no, we were minimally able to play our own music, let’s put it that way. We were pretty good, but we weren’t into ‘big and loud.’ We didn’t have that need, because I think it’s a need.

“Sort of, ‘If something is louder, it’s better.’ But for Carl and me, we were painting a canvas. Jimi was one of the best in the world, but they were more of a performance phenomenon, representing an era. We were more like painters, painting music with our guitars and our productions, and they were blasting it, I guess.”

Speaking of blasting it, there are some wild, uncharacteristically “big” guitar solos on some of the post–Smiley Smile albums the band produced as a team. For instance, who’s playing that crazy solo on Bluebirds Over the Mountain from 1969’s 20/20?

“Oh, god. That’s Eddie Carter, master of the guitar. He and Jimi were friends. So maybe you’re hearing some Jimi in there. Eddie played bass on all those tracks that Brian or I didn’t play on, and it was Eddie during the living room sessions [Editor’s note: The band often recorded in Brian Wilson’s Bel Air living room from 1967 to 1972]. But Eddie played guitar on Bluebirds...

Eddie Carter played guitar on Bluebirds... It was such a big deal at the time. You had to have a big guitar solo because all those big guitar guys were happening

“It was such a big deal at the time. You had to have a big guitar solo because all those big guitar guys were happening. So, hey, if the Beach Boys have a big guitar solo on their record, that’s really gonna be great! That’s really gonna help out. It didn’t work out as well as we thought it would.

“We joke with Eddie about it now because it was a really good solo but very out of character with what we were known for, as I mentioned earlier. It was kind of a clash of cultures, an experiment that went somewhat awry. But yeah, it was no big deal for Carl to say, ‘You play on this.’

“There were no egos in the band. Everybody has a threshold of what they do best. That’s what’s great about being in a group; if someone’s uncomfortable with something, let someone else do it. It’s always been about the song, the completed project. Get completion, get it done.”

How about that metallic-sounding heavy-fuzz guitar solo on Feel Flows from 1971’s Surf’s Up?

“That’s Carl. I just love that song. It’s Carl on the Wurlitzer too. That and Long Promised Road. He had that knack for playing the Wurlitzer; he got quite a sound on it, and the chorus was beyond real.

Speaking of great guitarists, what was it like touring with Jeff Beck in 2013?

“He’s an exhibitionist, man. He’s got that beautiful style. He showed me a couple of riffs and said, ‘You can do this, it’s really easy. It sounds incredibly complicated, but…’ [laughs] He just sees it differently, sees in different colors. He can’t believe I’m still playing with a pick!

“His hands are like the size of a football; his thumb is doing all the work. It’s hard to believe he can get that great sound, but he’s got it all dialed in. But yeah, we stood right next to each other on that tour. I had the best seat in the house.”

Damian is Editor-in-Chief of Guitar World magazine. In past lives, he was GW’s managing editor and online managing editor. He's written liner notes for major-label releases, including Stevie Ray Vaughan's 'The Complete Epic Recordings Collection' (Sony Legacy) and has interviewed everyone from Yngwie Malmsteen to Kevin Bacon (with a few memorable Eric Clapton chats thrown into the mix). Damian, a former member of Brooklyn's The Gas House Gorillas, was the sole guitarist in Mister Neutron, a trio that toured the U.S. and released three albums. He now plays in two NYC-area bands.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.