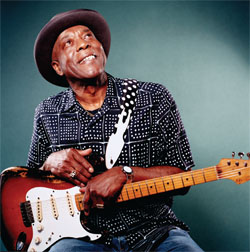

Buddy Guy: A Man and His Blues

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Originally printed in Guitar World Magazine, October 2005

Jimi Hendrix learned at his feet. Eric Clapton calls him "the greatest living guitarist." On the eve of his new release, I Got Dreams, blues legend Buddy Guy reflects on his greatest recordings.

Buddy Guy’s Legends club sits on a windswept Chicago street corner. It’s not one of those Disney-fied, touristy blues places but a bona fide neighborhood joint with neon beer signs and walls that have been spray painted black. The club’s upstairs offices are equally down to earth: dinged-up metal desks, clutter everywhere and a battery-challenged smoke alarm that chirps constantly. No one seems to notice.

Seated at a desk that looks like it could once have belonged to an automotive repo man, Buddy is dressed in a light-blue windbreaker and matching Kangol hat. His hands cradle an old black-and- white photograph that shows Buddy with Muddy Waters and Willie Dixon at the historic Chess recording studio in Chicago. The years seem to melt away as Buddy gazes down at the image.

“Man, you can see the expression on my face,” he says, beaming. “To sit there and play behind Muddy Waters—I was in heaven.”

At 70, Buddy Guy is our greatest living link between the blues’ storied past and its vibrant present. He has traded licks with the founding fathers of electric blues, the Sixties rock gods and today’s finest young bloods. As blues guitarists go, they just don’t come any better than Buddy. His utterly unique sense of phrasing seems hardwired to the emotional logic of choked-back tears. Astoundingly agile, he can make a Fender Stratocaster sing the proud exuberance of human sorrow transmuted to pure beauty.

Buddy’s brand new album is titled I Got Dreams. A soul-flavored disc, it shows the blues titan putting his distinctive stamp on tracks by legends like Wilson Pickett, Eddie Floyd and Johnny Taylor, and his own new composition “What Kind of Woman Is This.” The album was recorded in part at Memphis’ historic Royal Studio. Royal owner and noted R&B producer Willie Mitchell contributed horn arrangements on several tracks. Frequent Keith Richards collaborator Steve Jordan produced the star-studded disc, which also features Robert Randolph and Anthony Hamilton joining in on a version of Bob Dylan’s “Lay Lady Lay” that boasts the first ever Buddy Guy blues solo performed on electric sitar. “I never got a chance to do that before,” he says with a laugh.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Elsewhere on the album, Carlos Santana teams up with Buddy on a blazing rendition of the Screamin’ Jay Hawkins classic “I Put a Spell on You.” Recently, Santana has become a major Buddy Guy booster. The two are also collaborating on a duet album that should be out soon. And on a more youthful note, John Mayer makes a guest appearance on I Got Dreams, trading lines with Buddy on “I’ve Got Dreams to Remember.”

“It’s an Otis Redding song that John actually picked for me to do,” says Buddy. “He told me, ‘This song fits you. You can do something with this.’ At first I said, ‘Wait a minute, John, that’s not my type of stuff.’ Then I got in the studio and said, ‘Hey, this feels good!’ John and I have been jammin’ a while now. He’s a great young man, selling a lot of records. I feel so proud of him. Every once in a while the blues needs an Eric Clapton, Stevie Ray Vaughan or Johnny Lang to come along and give it a lift. ’Cause the blues has been fightin’ for life ever since I’ve been knowing it. But the way I love the blues, I’ll just go down with it.”

Mayer is the latest in a long line of noted guitarists who have paid homage to Buddy Guy. Jimi Hendrix literally knelt at Guy’s feet to study his astounding technique. Eric Clapton, another major acolyte, has repeatedly called Buddy “the greatest living guitarist.” Stevie Ray Vaughan never would have picked up a Stratocaster without Buddy’s inspiration. So it’s more than fitting that Buddy was admitted to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame this year, the latest in a parade of honors that time has brought in its wake.

“It’s like sitting on top of the world,” says Buddy of his induction. “But every award I ever received in my life, I accept it in honor of the people who should have got it long before me, like Son House, Mississippi Fred McDowell, Lightnin’ Hopkins and T-Bone Walker. All those guys should have had the awards that a lot of us are gettin’ now. So their name is on mine.”

In matters of blues history, Buddy possesses a ready and vivid memory. He seems to feel the bitterness of each rip-off and the glory of each musical triumph as if they happened yesterday. As he reflects on some of his greatest recordings, from the late Fifties to the present day, the recollections come flooding back, infusing the hallowed grooves with the living truth they call “the blues.”

RECORD/ARTIST

“Sit and Cry (the Blues)”/Buddy Guy

DATE 1958

WHY IT COUNTS Buddy’s very first single.

STUDIO Cobra Records, Chicago. “There was a little record store in front with 45s and 78s,” Buddy recalls. “You walked through to some old garage in the back, and that was Cobra Records. Just a car garage, man, but that’s where I was gettin’ that real sound you hear on that record.”

BACKSTORY Buddy left his native Louisiana and arrived in Chicago on September 25, 1957, hoping to land a contract with premiere blues label Chess Records. Initially, Chess passed, but rival label Cobra, headed by Eli Toscano, eagerly signed the new arrival to its subsidiary imprint, Artistic.

THE TRACK A slow, mournful blues meditation in G, punctuated by lachrymose sax drones and skittering piano. Buddy’s unrestrained vocal style is already very much intact on this debut release, and the expressive guitar lines and clean, concise 12-bar solo ably serve as counterpoint.

PRODUCTION NOTES The song’s slightly unusual chord structure audibly confounds the backing band at points, especially when they hit the bridge. Buddy makes a strong showing nonetheless.

BUDDY’S GEAR A Gibson Les Paul Goldtop, purchased on installment back in Louisiana. “The amp was either a little Gibson with two speakers in it or a Sears Roebuck,” Buddy adds.

KEY PLAYER Willie Dixon (1915–92) wrote the song and played bass on the date. This was the first of many Buddy Guy recordings that would be penned by Dixon, the blues’ own Cole Porter, Irving Berlin and William Shakespeare rolled into one. Dixon’s songs were recorded by Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, the Rolling Stones, Led Zeppelin and many others. Buddy still vividly remembers his first meeting with Willie, an imposingly large man who dwarfed the big upright bass that was his signature instrument:

“Willie Dixon come and got me and told me he was gonna take me to dinner. I figured, I just got here from Louisiana; I don’t have an education; now’s my time to just be cool—watch and learn. So we walks into this barbecue joint and Willie orders a whole fuckin’ chicken. I’m figurin’ we gon’ take a fork and knife, carve up the chicken, and me and him would eat it. But when the chicken come out, he picks it up, breaks it in half with his bare hands and start to eat the whole fuckin’ thing himself. He looks at me like, What you gon’ have?”

POSTSCRIPT Shortly after this session, Buddy’s Les Paul was stolen from the bandstand at a club where he was playing. Cobra Records didn’t last much longer either. “I think Eli Toscano got killed or drowned or something,” says Buddy. “I heard a lot of different stories about that.”

RECORD/ARTIST

“The First Time I Met the Blues”/Buddy Guy

DATE Recorded March 6, 1960

WHY IT COUNTS Buddy’s first single for Chess. One of the greatest and most influential blues recordings of all time. Beloved by Jimmy Page and many others.

STUDIO Chess Records, 2120 S. Michigan Ave., Chicago; now a historic landmark.

BACKSTORY After two singles on Artistic, Buddy easily made the jump to Chess, where he went on to cut a series of singles and served as a session guitarist to immortals like Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf. “You’d get $30 for making a session,” Buddy recalls. “And that was the best money you could make in Chicago. Working in clubs you’d only make, four, five or six dollars a night. Even Muddy was only making $12.”

Buddy’s producers and bosses at his new label were the brothers Phil and Leonard Chess. Polish immigrants and former liquor salesmen, the Chess brothers built the Chess and Checker labels into a blues empire, releasing classic discs by Muddy, Wolf, Little Walter, Sonny Boy Williamson, Elmore James and Jimmy Rogers, not to mention seminal early rock and roll sides by Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley. Buddy didn’t always see eye to eye with the Chess brothers, but the entrepreneurial siblings nonetheless produced some of his finest recordings and played an important role in developing many of his key stylistic trademarks.

THE TRACK A chilling blues allegory, “The First Time I Met the Blues” recounts a fateful crossroads encounter with the blues itself, here personified as an ominous manifestation of all life’s sufferings. Buddy’s plaintive vocal is underscored by some of the most stinging guitar playing ever committed to tape: frenzied bursts of pent-up emotion delivered with a razor-thin tone that cuts like a suicide’s arterial slash.

PRODUCTION NOTES Speaking of razor blades, the Chess brothers were by no means averse to slicing a master tape to suit length requirements or other commercial exigencies. Deft tape editing produced the eerily powerful opening to “The First Time I Met the Blues.” There is no instrumental prelude of any sort. We’re plunged straight into Buddy’s agonized vocal, immersed in the narrative before we know what’s hit us. “There originally was an intro,” Buddy reveals. “I could never start in singing like I did on that track without an intro. I had to get into it first. But I had a bad habit back then: some of my intros were too long. So they’d cut ’em out.”

The Chess siblings also suggested the keening, high-pitched vocal register Buddy employs on the track and which would become a signature element of his singing style. “Little Brother Montgomery [who wrote the Song] had made a hit of ‘The First Time I Met the Blues’ [in 1936],” Buddy remembers. “The Chess brothers told me I could do the song in a higher voice. They were kind of trying to lead me in the direction of B.B. King. Ain’t but one of them. But they want me to sing it kind of high. It’s one of the most talked-about songs I ever did for Chess.”

BUDDY’S GEAR This is perhaps the earliest track to feature Buddy’s Sunburst 1957 Fender Stratocaster, one of the most sacred artifacts in all of blues history. The guitar was purchased— just barely—shortly after the theft of Buddy’s Les Paul in ’58.

“I had to get down on my knees and beg this lady at this famous blues club called Theresa’s Lounge at 48th and Indiana,” he remembers. “And she finally loaned me the money for that Strat. I think it was $149 or $150, with case, strap and everything.”

Buddy chose a Stratocaster because it was the instrument of choice for his ax hero, Guitar Slim, whose highly theatrical stage performances inspired the style of showmanship that Buddy would later pass on to Jimi Hendrix. Buddy’s much-battered ’57 Strat was his main guitar until 1976, when it too was stolen. Before then, it was most often mated with a ’59 Fender Bassman amp. These two pieces of gear are very much the sound of early Buddy Guy recordings. Buddy quickly got into the habit of cranking the Bassman to the max and using the Strat’s volume and tone controls to achieve the rich tonal variations heard in his work.

“When I would record with Muddy and them, we used to drink wine, beer and whiskey and set it on the amp. So all the control knobs on my amp had frozen with dirt, booze, cigarette butts and all that. But that was okay, ’cause I didn’t need to move them anymore.’ All I had that worked on that amplifier was the on-and-off switch.”

KEY PLAYERS “The First Time I Met the Blues” was the first of many Buddy Guy sessions to feature the redoubtable Jack Meyers on electric bass, still a relatively new instrument when the record was made. (The first commercially available electric bass, the Fender Precision, was introduced in 1951.) “When the Fender bass first came along, I remember seeing this kid Jack Meyers play it with [guitarist] Earl Hooker’s band,” Buddy recounts. “Hooker actually owned the bass, so the only time that boy could play, he had to work with Earl Hooker. But I found out that Willie Dixon had a Fender bass that he’d pawned at a place on 47th and State. So I told that boy, ‘If you wanna play with me, I’ll go get that Fender out of pawn from Dixon.’ And I gave it to Jack, ’cause he was a good little bass player.”

On Buddy’s records, Meyer was often paired with ace Chess session drummer Fred Below (pronounced BEE-low), who here pounds the toms like some lost soul condemned to play the strip clubs of Hell for all eternity. Apparently, Below was a bit of a cutup in the studio. “They finally had to build a pen around him, like a cardboard box,” Buddy recalls, “so he couldn’t mess with anybody.”

RECORD/ARTIST

“My Home Is in the Delta”/Muddy Waters

DATE Recorded in September, 1963

WHY IT COUNTS Historic pairing of Buddy Guy with blues icon Muddy Waters on a track that marks Muddy’s return to his Mississippi Delta folk blues Roots

STUDIO Chess Records, 2120 S. Michigan Ave.

BACKSTORY The mid-Sixties folk boom created an enthusiastic interest in rural blues among predominantly white college youths. Eager to reach this new audience, the Chess brothers decided to “reposition” Muddy Waters—then the quintessential sharp-dressed, smoothtalking urban bluesman—as a humble Delta sharecropper. Thus, the classic Muddy Waters Folk Singer album was born.

“Chess heard about the college kids buying folk music,” Buddy recalls, “so they called Muddy in and they wanted to rush one of those records out on him. They gave him a train ticket and told him to go down South and find some of those older guys who play that kind of stuff. And Muddy said, ‘Set the fuckin’ session up for tomorrow. I got it.’ They thought Muddy was gonna call some old-time guy and put him on a train. When Leonard Chess came in that morning and saw me sitting there, that guy called me a ‘motherf**ker’ so many times, I almost cried and left the studio. But Muddy told him, ‘Shut the fuck up and listen.’ After we got done playing, they stood there with their mouth wide open. All they could say to me was, ‘Motherf**ker, how’d you know that?’”

THE TRACK With Clifton James on the drum kit, this is hardly authentic Delta folk blues. But Waters’ composition receives an eloquently understated acoustic reading, sensitively supported by Willie Dixon’s supple standup bass. With Muddy playing mostly single-note leads and embellishments on slide, Buddy is essentially the main guitarist on the track. He proves a confident and resourceful interpreter of the acoustic blues idiom. Check that graceful riff—somewhat in the manner of Robert. Jr. Lockwood— on the V chord of the second verse. As Buddy himself says, “I know how to back Muddy up on that shit, man.”

PRODUCTION NOTES Session photos depict a very minimal recording setup, with just one mic for Waters, Guy and Dixon. As a result, the track has a very open, ambient feel—the sound of that hallowed room at 2120 S. Michigan Avenue.

BUDDY’S GEAR At the time of this recording, Buddy didn’t even own an acoustic guitar. Muddy Waters lent him one of his archtops for the date.

KEY PLAYER McKinley Morganfield, a.k.a. Muddy Waters (1915–1983), really did grow up in rural Mississippi. He worked on a plantation and was recorded by folklorist Alan Lomax before he traveled north in 1943 and became the principal architect and undisputed king of Chicago blues. Muddy had a huge influence on the Rolling Stones, who took their name from one of his songs, and countless other rock and rollers who have found their hearts in the blues.

POSTSCRIPT The folk blues craze was not confined to bookish white kids in America; their European counterparts were arguably even more fanatical. And so Buddy first toured Europe in 1965 as part of the American Folk Blues Festival, a package tour organized by German promoters Horst Lippmann and Fritz Rau and featuring greats like Mississippi Fred McDowell, Big Mama Thornton, Eddie Boyd and Roosevelt Sykes. It was on German soil, ironically, that Buddy first met one of his greatest blues heroes: John Lee Hooker. Growing up in Lettsworth, Louisiana, Buddy had just about worn out a copy of Hooker’s classic “Boogie Chillin’.” When Buddy’s parents confiscated the phonograph needle, he’d take a stickpin—a piece of jewelry for securing a necktie—hold it in his teeth and place it on the record, letting Hooker’s driving rhythms resonate in his skull. And on one fateful morning in Baden Baden in 1965, Buddy Guy finally came face to face with his hero—although he didn’t realize it was Hooker at first.

“Everybody was heavy drinkers back then,” Buddy says. “And when I went down to breakfast in the morning they had whiskey eggs. I sat in the corner with an acoustic guitar and started playin’ ‘Boogie Chillin’,’ which was the first thing I’d learned how to play by myself. And this guy comes up, he was drinkin’ and stutterin’ bad. ‘Y-y-y-you t-t-t-tryin’ to play J-J-J-ohnny…’ I say, ‘Yeah, I guess so. I’m just trying to figure out who the fuck you are, stutterin’ so.’ Finally Fred Below said, ‘That’s John Lee Hooker right there!’ And Hooker just started to laugh. Boy, he laughed so hard he cried. We became best friends from that day till the day he died. I was at his funeral.”

RECORD/ARTIST

“Man of Many Words”/Buddy Guy and Junior Wells

DATE Recorded in October, 1970

WHY IT COUNTS A staple of the Buddy Guy repertoire and one of Buddy’s own compositions. His first significant collaboration with Eric Clapton.

STUDIO Criteria Recording, 1755 NE 149th St., Miami

BACKSTORY Buddy first teamed up with harmonica ace Junior Wells in the mid Sixties. They became a popular live act and by 1970 had landed a highvisibility opening spot on the Rolling Stones tour. During this period, Eric Clapton was just finishing off his classic Derek and the Dominoes album, Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs, while getting deeper and deeper into what would become a debilitating heroin addiction. Clapton was an avid Buddy Guy fan, and back in ’65 had slept in a van with other members of the Yardbirds to be among the first in a venue where Buddy was playing on his aforementioned maiden voyage to Europe. Five years later, as final mixes of Layla were underway, Eric Clapton decided he wanted to make a record with Buddy Guy.

“Ahmet Ertegun [head of Derek and the Dominoes’ label, Atlantic Records] was hangin’ out with Clapton,” Buddy explains. “At this time [Atlantic recording artist] Aretha Franklin was poppin’ and everything Ertegun touched was turning to gold. Clapton told him, ‘I don’t know why you want to record me. The best guitar player in the world is touring with the Rolling Stones right now.’ So they grabbed a plane, flew to Paris and watched me and Junior Wells open the show for the Stones that night. Afterward [Ertegun] just walks up and says, ‘I’ll make a fuckin’ hit record on you. When you get off this tour with the Stones, come straight to Miami and record an album for Atlantic Records.’ We went down there, and Eric told me later on he hardly even remembers making that record. He was high all the time.”

THE TRACK An uptempo funk soul workout that marries an insistent G7 guitar riff to a wicked, syncopated bass line. Buddy busts loose as a soul-preachin’ loverman. “I was listening to a lot of Otis Redding and those guys, who were selling a lot of records then,” he recalls of his inspiration for writing the tune. “ ’Cause back then, just like now, you can make the best blues record in the world, but it won’t get no airplay.”

The slippery, open-ended groove provides an ideal vehicle for some of the most fast-paced, manic soloing ever to issue from the fingers and guitar of Buddy Guy. Yeah, he flubs a few notes, but the whole thing beautifully encapsulates the breezy wild energy of that hastily organized date down in Miami.

PRODUCTION NOTES There were no rehearsals or preproduction. What you hear is pretty much what Buddy and the band threw down in the studio. The whole thing was a little too nonchalant for Atlantic, who initially shelved the project. It wasn’t until two years later, when Buddy recorded two extra songs with the J. Geils Band, that the label finally had what it deemed was an entire album of releaseworthy material. “Man of Many Words” became the lead track on 1972’s Buddy Guy and Junior Wells Play the Blues.

BUDDY’S GEAR His ’57 Strat and Bassman amp.

KEY PLAYERS Eric Clapton is on second guitar. New Orleans keyboard legend Dr. John (Mac Rebennack) is on piano. The rhythm section features Derek and the Dominoes’ bassist Carl Radle and drummer Jim Gordon—an all-star cast captured on tape by engineering legend Tom Dowd.

RECORD/ARTIST

“Mustang Sally”/Buddy Guy

DATE 1991

WHY IT COUNTS Historic pairing of Buddy and his fellow guitar legend Jeff Beck on Buddy’s “comeback” album, Damn Right I Got the Blues.

STUDIO Battery Studios, 14/16 Chaplin Rd., London

BACKSTORY The Seventies and Eighties were lean years for Buddy Guy. With no American recording contract, he barely got by reprising his past triumphs for various European labels. His luck changed when Eric Clapton invited him to take part in the all-star 24 Nights concerts at London’s Royal Albert Hall in 1990 and ’91. This led to a contract with Silvertone Records—still Buddy’s label today—and a major comeback.

“This British guy comes up to me backstage at the Royal Albert Hall and says, ‘I wanna sign you to do this album.’ I’m sayin’, ‘Okay Buddy, this is British guys now. Here’s your Johnny-come-later Jimi Hendrix chance. You can do your own thing now.’ I went to Battery Studios in England, cut Damn Right I Got the Blues, and that was the biggest record I ever had.”

THE TRACK A stomping, uptown rendition of the R&B classic made famous by Wilson Pickett. Buddy Guy’s “Mustang” boasts a big horn section, soul-sister backing vocals and, of course, the over-the-top guitar stylings of Jeff Beck, whose electrifying leads go line for line with Buddy’s brash vocal. Beck is another Strat-bearing British rock guitar god who got major inspiration when Buddy landed in England in ’65. Here he returns the favor.

PRODUCTION NOTES “Beck and I are the best of friends,” says Buddy. “He come in the studio after we cut the basic track and they plugged his guitar through the engineer room [i.e. control room]. I was in the engineer room when he put that guitar track on there. Man, that guy can play.”

BUDDY’S GEAR For most of the Damn Right, I’ve Got the Blues sessions, Buddy played an Eric Clapton Signature Model Fender Strat, procured from a London music shop. He liked the guitar so much that it became the basis for Fender’s Buddy Guy Signature Model Strat, first released commercially in 1995.

KEY PLAYERS Beck and Buddy are more than enough talent for any track, but the massively solid backbeat on this recording was provided by Little Feat drummer Richie Hayward.

POSTSCRIPT According to Buddy’s guitar tech Mark Messner, the guitarist currently owns seven polka-dot Strats, many of them equipped with the same built-in preamp found in the Eric Clapton signature Strat. Four of Buddy’s polkadot Strats were made by the Fender Custom Shop, with pickups ranging from Lace sensors to Texas Specials. The remaining three are production- line Buddy Guy Signature models from Fender’s manufacturing facility in Mexico. One of these instruments is equipped with ’59 humbuckers and another has vintage noiseless pickups. Buddy often uses the latter guitar when he plays at his Legends club, which has significant buzz issues, according to Messner.

Most recently, Buddy has taken to playing a ’72 Telecaster Deluxe onstage. His live amp rig consists of a Fender ’59 reissue Bassman LTD, a Vibraverb and an Eighties Marshall JCM800 head through a Tone Tubby 1x12 cube. The latter is isolated and miked offstage.

RECORD/ARTIST

“Baby Please Don’t Leave Me”/Buddy Guy

DATE 2001

WHY IT COUNTS Buddy Guy finds the missing link between blues and punk.

STUDIO Sweet Tea, Oxford, Mississippi

BACKSTORY By the start of the 21st Century, Buddy Guy was ready to reinvent himself once again. For his 2001 album, Sweet Tea, record producer Dennis Herring teamed him up with a coterie of younger players from the world of post-punk and alternative rock, including Squirrel Nut Zippers/Knockdown Society guitarist Jimbo Mathus and Elvis Costello’s rhythm section: bassist Davey Faragher and drummer Pete Thomas. In the cozy confines of Herring’s Sweet Tea studio, located in the picturesque small town of Oxford, Mississippi, Buddy and his new backup musicians dug into a selection of songs drawn principally from the repertoires of North Mississippi bluesmen Junior Kimbrough and T-Model Ford. Both artists record for Fat Possum Records. The maverick raw-blues imprint, distributed by L.A. punk label Epitaph, has been responsible for turning a whole new generation of punk rockers on to the blues.

“When I first came to Chicago, I found the Wolf, Otis Rush, Otis Span and all those guys,” says Buddy. “I thought I done dug up everything there is. But when I went down there [to Mississippi], Dennis Herring started bringing up this Junior Kimbrough stuff. He’s a guy never hardly did leave Mississippi. I said, ‘Wow, man. I didn’t dig deep enough.’ It goes to show, you never get too old to learn.”

THE TRACK A slow, brooding, seven-minute excursion in C, built off a Hendrix-like guitar riff and a grainy, subsonic bass that never ventures too far from the tonic. Liberated from the 12-bar grid, Buddy soars into the stratosphere. Fanciful, full-blown rock production values—flangy, echoed vocals and a soaking wet, sustaining lead tone—bring out aspects of Buddy’s prodigious talent never quite captured by the more documentary approach of his recordings from the Nineties and earlier.

PRODUCTION NOTES “I cut that record in the hall of Sweet Tea,” says Buddy. “The band was set up in the studio. I could see ’em through a glass door. But I was in the hall with all these amps. Dennis Herring has a lot of these great old amps. A lot of those guitar sounds you hear on that record had something to do with him. He’s got one of them old [mixing] boards that he got out of L.A. somewhere. It’s as close as you can get to the old studios.”

KEY PLAYER Also on the sessions was the drummer Spam, veteran of many Fat Possum recordings. Although he had suffered a mild stroke, Spam managed to impress Buddy, who told him, “Shit, if I woulda saw you before you had the stroke, I probably woulda moved down here to Mississippi just to play with you.”

POSTSCRIPT Touring in the aftermath of Sweet Tea’s release, Buddy used a Fender Cyber- Twin and Bassman Reissue, a Gibson Gold Tone and a Bogner to recreate some of the vintage bass amps heard on the album.