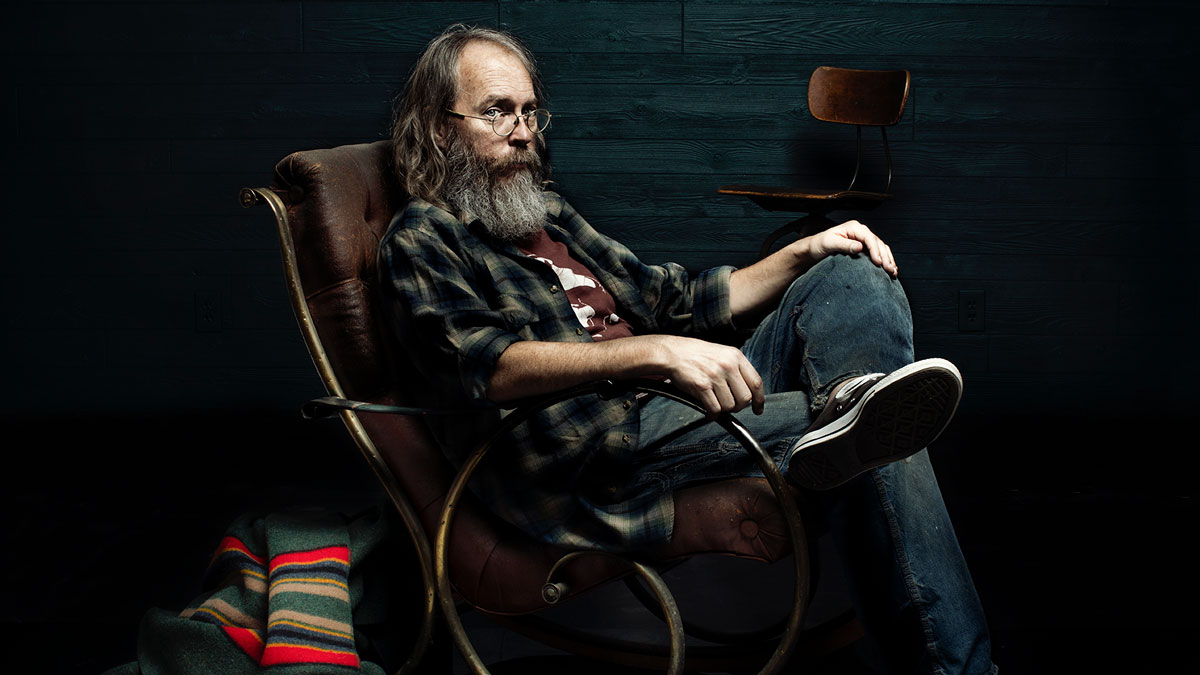

Charlie Parr: “My physical setbacks have strengthened my relationship to the guitar… we're still here together”

Drone bands, resonators and reflection with the Minnesotan picker

Charlie Parr swims upstream. As a kid, when other children were asking for electric guitars, Parr wanted a National. Since he got his first resonator, he’s spent the better part of his life dedicated to touring the contemporary country blues music for which he has slowly and steadily become renowned.

Parr’s a unique, idiosyncratic songwriter. He works in homeless outreach and he notices things that others don’t. He documents stories and personal reflections that feel palpably real, woven from the frayed edges of America’s social fabric.

Unlike so many of the revivalist acts clogging the traditional circuit, Parr doesn’t sit still as a musician. He plays in a drone band (charli III), constantly rewrites his own material and has doggedly overcome severe setbacks to his playing (more on that below).

His new album Last of the Better Days Ahead dwells on the challenge of middle age. “This weird and unfamiliar kind of feeling,” says Parr. “Where I still have things to look forward to, but I also have more things that I'm looking back on and remembering.”

We spoke to Parr about creativity and age, the challenging evolution of his vibrant fingerstyle playing and the beloved resonators and Guild 12-strings that have been his most faithful companions throughout his journeys…

Something that’s been mentioned in the writing around this record is the idea of the brain’s link between memory and imagination. Where did you first learn about that?

"Oh, I can't even remember! I think I was reading an article about the brain. I'm a very dangerous kind of philosopher, because I don't know anything. I’m shooting from the hip about half the time, but I read this article about how the portion of the brain that's responsible for memory is also responsible for imagination. And that's fascinating to me. Even if I didn't read any farther than that, I can run with that idea. That's going to fuel some fires for a long time for me.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

"And I can see that in my own life. I'll have a memory that has been very important to me for my whole life. I'll sit down with my sister, my mother, and realize that I made half of it up. They’ll correct me. Which is disappointing! So I've stopped recounting memories to family members who might be able to verify it..."

The concept reminded me of research that adults have a weaker creative ability than children. Do you find your creative instinct is growing stronger or weaker as you grow older?

"I think it's growing weaker, of course, but I feel like it's something I also take the time to exercise quite a bit. I'm trying not to let go of it easily: that creative faculty. So I indulge in experimental music on the side – I write as much as I can and try to ensure that it at least gets some exercise. I'm not gonna let go of it easily."

Tell me about the experimental music. What has playing in a drone band given you as a musician?

"Well, on the new record, the last piece of music [Decoration Day] is a 16-minute-long dive into that world. I'm very much of the opinion that the songs that I've written in the past are still not finished. I like taking them out of where they are and trying to reframe them.

"Being in this band has given me the chance to practice improvisation and try to get better at being in spaces that I'm not normally in, musically, and see if I have the creativity to find my way out of them. Then I can use those new skills to take songs that I wrote 10/20 years ago, and start to reframe them and see what they do. For me, that's been super-valuable."

That need to reimagine your approach to the guitar seems to have happened a few times in your life. In 2009, you developed a brain disorder called focal dystonia, which limited your fingerpicking ability. Then in 2018, you had a skateboarding accident, which damaged your shoulder and left you playing lap-style for a while. Do you feel like those challenges have ultimately been beneficial to your playing?

I'm more excited about the guitar than I feel like I've been in my lifetime, because it's still a gift that I have, and I'm grateful for it

"Well, initially, it sure did not feel beneficial. I was devastated with those events, you know? Looking back on it now, I'm – I hate to use the words ‘proud of myself’, because I don't know if that's appropriate – but I feel good about the fact that I didn't quit. I persevered. I decided to find a way that I could play the instrument and still hear my voice in there somehow.

"What used to be fingerstyle, for me, turned into something completely different. I'm not able to use all my fingers because of focal dystonia and I have to hold my right hand in a specific way in order for it to work at all, but you know, I'm doing it, and it's not causing me any pain.

"And I'm more excited about the guitar than I feel like I've been in my lifetime, because it's still a gift that I have, and I'm grateful for it. Maybe that's the upshot of it: just gratitude. To still be able to participate and feel like this has strengthened my relationship to the instrument, because we're still here together."

Your playing nonetheless feels really vibrant – I think thanks in part to your dynamic picking style. Do you use picks now?

"Yeah. I didn't use picks for a long time when I was starting out, but one of the things that focal dystonia did was it took all the strength out of my hand. I used to play hard and then back off to get to where I wanted to be dynamic-wise, but when the strength went out of my hand, I couldn't make the guitar make enough sound to participate in dynamics at all.

"And so I started using picks, because then I don't have to play hard to get to get back up to that space. Especially with the 12-string, if you're not able to get the initial attack rate, you're only going to get the one string – and you want both of them! So I started using picks and I found that I can get those dynamics by either laying back even farther or digging in a little harder. I'm not a heavy player like I used to be."

Did you have to build that technique up or did you already have that muscle memory from your previous playing?

One of the things that I do when I notice that my patterns are getting stale is to start letting my thumb participate in the melody

"No, I had to work kind of hard on that. Because I was used to using three fingers and a thumb and those things went away. [Fortunately] I got a chance to open for Doc Watson on a festival in South Carolina the year before he died. I’d never gotten to see Doc Watson play in person even though I've been a fan of him since I was a kid, and seeing him go from flatpicking to fingerstyle was really, really inspirational.

"I started thinking about other guitar players who only use two fingers: Bukka White, for example, or Mance Lipscomb and Reverend Gary Davis is probably the most famous example. I started doing like a deep listen and thinking about what they had to do to maintain the tempo. My tendency would be to lose the vibe trying to go too fast. So I did a lot of exercises where I’d play very slowly, let myself speed up to the tempo I wanted – and then an important part of the exercise for me – to slow back down again, to develop that kind of sense of control."

What tips do you have for people trying to capture a bit of that energy in their own fingerstyle playing?

"Well, a lot of these techniques have been developed because of trauma for me, so I'm not sure if they're actually viable. But there are a couple of things. When you’re playing a Piedmont style thing, for example, your thumb is doing the rhythm and your fingers are doing the melody of the song.

"So one of the things that I do when I notice that my patterns are getting stale is to start letting my thumb participate in the melody. I’m dropping out a lot of that kind of alternating thumb rhythm, but without losing the tempo. Which is kind of a thing if you listen to Dock Boggs, for example, the banjo player or Roscoe Holcomb, another two-finger banjo player. That's been very helpful to me."

What are your main instruments currently?

"Well, [living in] pandemic world ended up with me getting having to get rid of a lot of guitars, just to keep the lights on. But one that I absolutely could not sell and was instrumental on the recording is my Mule Tricone – that's made in Saginaw, Michigan at the Mule Resonator Company. That's a stainless steel-bodied instrument that looks like a regular old National-style single cone, but it's actually got a tricone well.

"It's a beautiful sound. It has a good amount of attack, but it also has a long decay. Normally, in a regular single cone you get a very aggressive attack, but not as much sustain as a tricone. My guitar kind of combines those two worlds together.

"I also use a silver slide made in Germany that gives me a lot of tonal subtlety that I can use to exploit that sustain. It's a unique instrument. I've really found it to be something that I can't replace with any other guitar."

So that guitar lasted the pandemic. What else has been key?

"Well, the newest member of the family has been another guitar Mule made and it’s called a Mavis. It’s a solid wood body guitar with a single resonator in it and a mini-humbucker like in a Firebird. So it's more electric than it is acoustic, even though it's a resonator guitar through and through. I have it strung with baritone strings and tuned three steps below [standard] pitch. So it's at the bottom of its capacity. And I think two of the songs on the record were done that way with that Mavis.

"I like this guitar a lot, actually. It has started to become kind of my main guitar because it's really versatile. It’s producing a lot of the things that I like about resonator guitars, but it's also doing it without any of the problems with amplifying a resonator guitar."

What is your favored 12-string?

"The only 12-string I have nowadays is a 1966 Guild F112 that I've had for decades and dearly love, even though it's getting a little too old to take on the road. It's just a little fragile. It's a year older than me, so I guess that makes sense! I'm kind of in the market for a new 12-string, so we'll see how the gigs go. Unfortunately I had to sell a really nice Guild 12-string during pandemic world and I'm hoping to replace it again.

"With Guilds, it’s not a flashy thing. You're not showing up with a Flying V or anything like that. But it does what it does. And it does it all the time. And it does it better than anything else. You don't need to worry, 'Oh, my 12-string's hard to keep in tune.' Because Guilds are not hard to keep in tune and they're not persnickety. I think that's why a lot of people just kind of rely on them. There’s something comforting about them."

What do you look for in the instruments you buy? What are the qualities that are most important to you?

I can't stand the records that I did before. I don't like them! And I'm sure this record will become part of that club as well

"Well, I'm kind of fussy about guitars. So I need to sit with it. It’s really important for me to have a guitar that's well-balanced, which, with resonator guitars, is not easy. The Mule that I have is extremely well-balanced, so I can concentrate on playing the guitar and not have to worry about keeping it in one place. So that's important to me.

"I'm fussy about the neck, too. I want something more substantial. The necks on my Mules are wide and flat. I've really gotten used to that, and the neck on my Guild is the same way.

"The problem with electric guitars for me is finding an instrument that has that. I ended up having Creston Lea from Vermont build me a guitar that looks kind of like a non-reverse Firebird [Read more about Charlie Parr’s Spruce Custom]. But the neck is very specifically deeper and wider than normal electric guitars are, so I feel more comfortable with it."

You’re addressing some big ideas on Last of the Better Days Ahead. How close did you get to what you had in mind with the album? Is that even relevant?

"I don't know that it is. Now that it's been done for a while, my problem is that the songs are still morphing along on their merry little way. I’m presenting them in performances and they don't sound the same anymore. They're different. Their tempos are slightly different. But I mean that's life. I can't stand the records that I did before. I don't like them! And I'm sure this record will become part of that club as well.

"Right now, I think I got as close as I could get. And that's great. I think the problem is going to come when you get when you nail it, you know? That would be an indicator for me that something is about to change, or bad things are gonna happen!"

- Last of the Better Days Ahead is out now via Smithsonian Folkways.

Matt is Deputy Editor for GuitarWorld.com. Before that he spent 10 years as a freelance music journalist, interviewing artists for the likes of Total Guitar, Guitarist, Guitar World, MusicRadar, NME.com, DJ Mag and Electronic Sound. In 2020, he launched CreativeMoney.co.uk, which aims to share the ideas that make creative lifestyles more sustainable. He plays guitar, but should not be allowed near your delay pedals.