Cliff Williams: “AC/DC’s songs are very guitar-driven, so I don’t need to be noodling around underneath. I just need to be driving it“

The AC/DC bassist on why four strings is enough, the importance of the pocket, and why jazz made him twitchy

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

”Oh dear. Be kind!” quips Cliff Williams when I tell him that I’ve been carefully listening to the bass parts on his new album, Power Up, in preparation for this interview. He’s kidding, of course – you don’t play stadiums for 40 years without developing a thick skin – but at the same time, he’s definitely not on familiar ground today.

This is because Cliff is in AC/DC, a band dominated since its inception by huge electric guitars and vocals, rather than bass guitar, drums, or anything else.

The huge production of the semi-British, semi-Australian band’s shows, the cannons, the lasers, the inflatable ‘colleague’ Rosie, the pyro, the crowd participation, the massive sense of uncompromising heritage – arguably these are also more important to AC/DC... Or so you’d think, if you were less well informed on these matters than you and me.'

This is superficial, of course. In reality, Williams’ bass parts are utterly integral to his band’s music.

Listen to more or less any of the guitar riffs that anchor AC/DC, the majority of which were written by the band’s late leader and rhythm guitarist Malcolm Young: their staccato nature leaves loads of space for the bass. Listen to the sparse, impactful drum patterns; they don’t drown him out with rolls or flourishes.

Jazz made me feel kinda twitchy. Too busy! My wife hated it, so we got out of there. So no, jazz is not for me

No, he’s all over the sound of AC/DC, and nowhere more so than on their new album, Power Up. The key to his bass style is simplicity and economy. If, as we do today, we want to drill down to the philosophy behind his millimetrically precise playing, it’s actually easier to ask him what he doesn’t do.

For starters, he doesn’t do five-string basses. “I get lost with the damn thing,” he chuckles. “That bottom string – what is it, a B? I only play a five-string bass when I’m out somewhere, and someone’s playing, and they say ,‘Come and have a play on a couple of songs’ and the bass player has a five-string. I don’t know where the hell I am, because I instinctively go to the bottom string. Wrong! Haha!’

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

He doesn’t bother looking at YouTube for the next big thing in bass.

“I’m stuck with the old stuff that I know and love. I still listen to Little Feat. There’s probably a lot of great young bass players out there, but I’m just not aware of them. I do think Pino Palladino is a great player, and I had the distinct pleasure of having a beer with Rocco Prestia when Tower Of Power were playing in Florida. We went along and I got a chance to talk with him.”

He doesn’t listen to jazz. “My wife and I went and saw John McLaughlin years ago playing at some club, and it made me feel uncomfortable. It made me feel kinda twitchy. Too busy! My wife hated it, so we got out of there. So no, jazz is not for me. I know there’s some awesome bass players there, though.”

The songs are very guitar- and chorus-driven, so I don’t need to be noodling around underneath. I just need to be playing the framework, and driving it as part of the rhythm section

He doesn’t play slap bass. Yes, I asked him that question, even though I had a good idea what the answer would be. I make a habit of asking inappropriate questions about slap, just to see what will happen.

“I don’t think the boys would have really appreciated me trying to slap around. They would have slapped me around, I think,” he snickers.

“I can’t say I didn’t try it, sitting around in a room on my own, just for shits and giggles. But I never wanted to be very good at it. Flea’s a monster at that stuff, and there are other guys out there that are really good – but it was not for me.”

He’s also not trying to improve or evolve his bass playing. “I don’t think it’s changed much. I just try and do my bit as best I can,” he muses. “If anything, it’s a little simpler. I try to bring it down to what it needs.”

All this stuff is extraneous, frankly – and make no mistake, Williams is already a machine on his instrument. Listen to any of his recorded bass tracks: his grasp of pocket playing is awe-inspiring, although he can push and pull against the beat at will; his muting is extraordinary, clipping off notes with precision-engineered accuracy; and he redefines the idea of consistency.

How did he arrive at this style, we ask? “It just developed, from playing with the guys, and with the songs that we play,” he explains. “The songs are very guitar- and chorus-driven, so I don’t need to be noodling around underneath. I just need to be playing the framework, and driving it as part of the rhythm section. That’s how I’ve always approached it, and it’s just developed over the years to where it is now.

”When I play, I mute with the pad of my hand; it’s just a feel thing. If the string is ringing out a little too much, on this note here or there, I’ll just mute it slightly, just to keep it all even.”

Does he change up his bass parts on tour? “On live stuff, sometimes I’ll vary it a little bit; I might put something in that I feel might work, and try it, but that’s about it. It’s about the song first, most definitely, and it’s about trying to play the song as best you possibly can every night.”

An attitude which the bassists who first influenced Williams would appreciate, we think. He recalls the first time that bass impressed him, as a young kid in Essex.

“I remember standing outside a youth club and listening to some soul music, and hearing the basslines. This was before I’d started playing an instrument. I just stood outside and listened to the bass – it was incredible stuff.

“I had a buddy that somehow got hold of a lot of American blues records, and I’d go over to his place and we’d listen to them, and I don’t know who the players were, but it was a type of music that really attracted me. I was definitely in awe of the James Jamersons of the world: In fact, it might have been him who I first heard playing.”

By the early '70s, Williams was making his name in the psychedelic band Home, but he never listens to their music any more, he tells us.

“My wife loves [the 1973 LP] The Alchemist, so now and then we’ll put that on, but other than that I don’t listen to Home that much. You know what, I’ll have a listen. That’s a long, long time ago. Damn, is it nearly 50 years ago?”

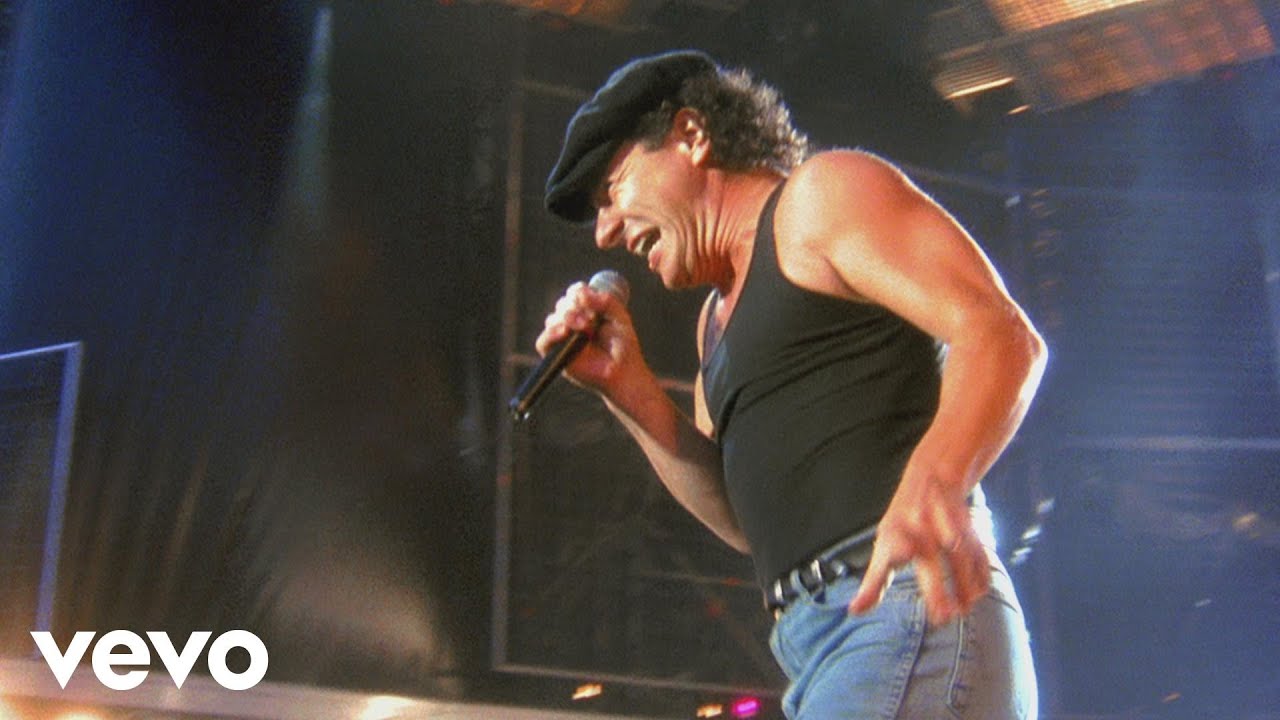

Williams joined AC/DC in 1977, three years before their singer Bon Scott died of a booze and/or heroin overdose, depending on which source you consult, and Brian Johnson was recruited for the band’s imperial phase.

Several decades later, AC/DC – now Williams plus Johnson, drummer Phil Rudd, and guitarists Angus and Stevie Young, who are respectively Malcolm’s brother and nephew – have had a chaotic time of it over the last six years or so.

The band’s 16th album, Rock Or Bust, appeared in 2014 and was their first without Malcolm, who was suffering from dementia.

The following tour, on which Stevie took his uncle’s place, also included a replacement drummer, Chris Slade, depping for the sidelined Rudd, who was working through some rather serious legal issues.

I don’t think the boys would have appreciated me slapping around... They’d slap me around!

Two years later, Johnson quit the band mid-tour with severe hearing damage, although the dates were completed thanks to the appearance of a certain Axl Rose of Guns N’ Roses.

Also in 2016, Williams announced his retirement: then 66 years old, the bassist had been treading the boards with AC/DC since 1979, and had definitely earned a break. And yet here he is once more, just when we thought we’d seen the last of him...

“I thought I’d seen the last of me too, haha!” he guffaws. “Look, I spoke to Angus on the Rock Or Bust tour – I said that I felt that I was done. It was my time, I guess. Phil had done the recording and then never did come on the road with us.

“He had his issues, and that’s that, you know, so we had Chris Slade come in to replace Phil. And then of course we had that terrible thing with Brian, he really needed to stop, so Axl came in and did a bang-up job, God bless him, and got us through to the end of it.”

As Angus said, you can’t have a tour called Rock Or Bust and [then go] bust, so we wanted to finish it, which we did.

He continues: “As Angus said, you can’t have a tour called Rock Or Bust and [then go] bust, so we wanted to finish it, which we did. And then that was it—we all went home and I was pretty much done. But Angus and Sony reached out a couple of years ago, asking if we would have any interest in getting together to do an album with Malcolm in mind.”

This isn’t the first time that AC/DC has reconvened after the loss of a member, he reminds us, citing a certain planet-sized album. “Back In Black had Bon Scott in mind. This album has Malcolm in mind – and because it was Brian and Angus and Phil and Stevie, I wanted to do it. And it went really well.”

Describing Malcolm Young as a “real strong character, like his brother”, Williams says of his late colleague: “He wrote some awesome stuff and he was an unbelievable player to play with. A solid guy, a totally solid guy. We were talking about this the other day – it’s like he’s still there. Not being soppy and hippie about it, but it’s a feeling that we all have, so hopefully he’s looking down and liking it.”

Our hunch is that, yes, if Malcolm Young is indeed relaxing in some hard-rock Valhalla and listening to Power Up, he’ll like what he hears. It’s punchy, upbeat and faithful to the sound that made AC/DC famous, but that doesn’t mean it’s one-dimensional.

God bless Brendan, he’s just a fantastic producer to work with

Listen to the thoughtful quasi-ballad Through The Mists Of Time if you want to know what I mean. Williams is quick to credit producer Brendan O’Brien for the vibrant feel of the new album. “God bless Brendan, he’s just a fantastic producer to work with,” he says. “He keeps it fresh, so you’re not sitting around because there’s always work going on. I couldn’t have been happier.”

Did he mic up one of his Ampegs in the studio, or go straight into the desk? “We did a bit of everything. We had the Ampegs set up, and an Avalon DI, and one other DI into the desk as well, so there was several different feeds that they put together. The way we record a take is that we’ll all go for it, and if it’s good then that’s it. If not, we’ll go back and do it again. You listen back, and you can feel if there’s something that’s not what it’s supposed to be.”

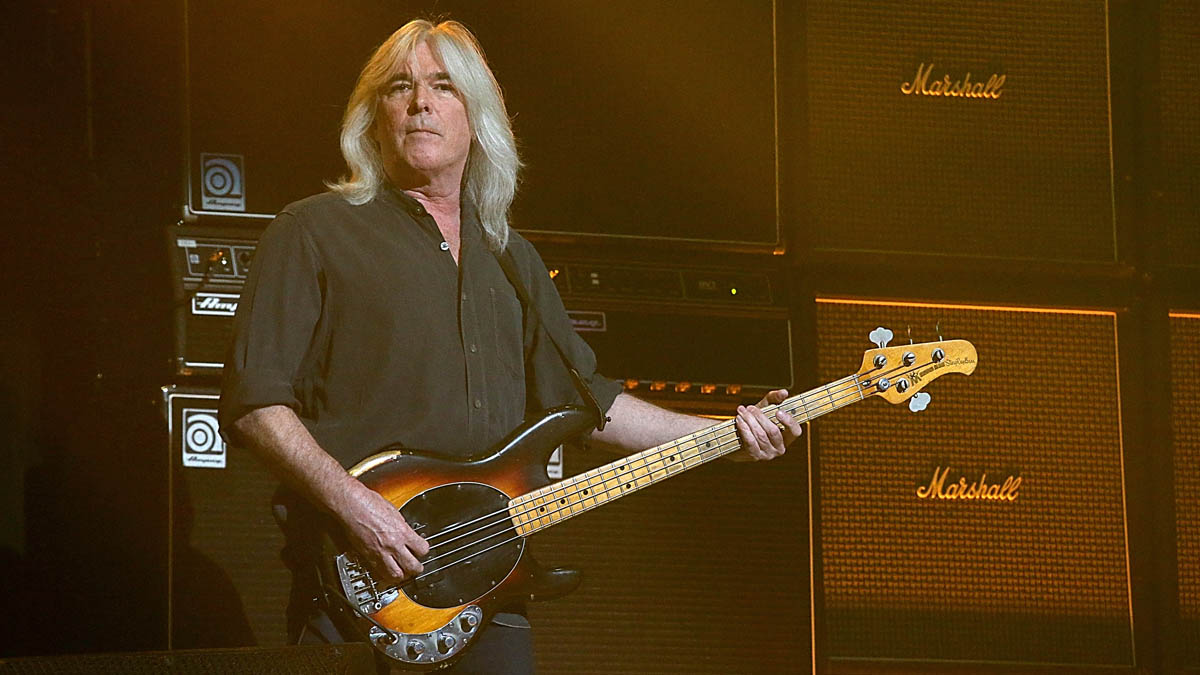

The bass parts came from Williams’ trusty Ernie Ball Music Man Stingray, the 1979 model that has traveled the world more times than anyone can possibly remember.

“It’s always been my mainstay, and I’ve stuck with it, for the most part,” he considers. “It’s taken a beating over 40 years. I wandered off here and there a little bit. I used a Fender Jazz for a while, although actually that might have been before the Music Man. I also played a Gibson Thunderbird for a bit, but not for very long.”

This leads us to the new Cliff Williams Signature Stingray, announced earlier this year and modeled on his 1979 original. “It’s a fantastic bass,” he says. “I was blown away by that. They had my old number one bass for over a year, I just got it back a couple of weeks ago, and they did a bang-up job of it. It really is impressive.”

Did Ernie Ball’s team measure up the exact dimensions of the old bass?

“Yeah, all of that. Every nick and ding and all the rest of it, cosmetically, they reproduced, but they got inside the thing too, and the pickups are tweaked exactly like mine. The whole thing is faithfully reproduced. They sent me a prototype and another one, so we had the three basses together and we went through each one – and I knew which bass my number one was, but they’re so damn close it’s very impressive.”

He adds: “Those basses have even got a Sharpie mark on the treble knob, because if you have it full on, it’s real glassy, so if you wind it back just a wee bit that glass goes away and you get a good, solid punch. They’ve even reproduced that on the signature bass, so you can dial that in. It sounds great.”

About 15 years ago I took a fall, and put my hand out to break my fall, right onto some broken glass. It cut the nerves and tendons in my left hand. I had two surgeries for that, and lots of rehab

Armed with a new bass and a new album, Williams seems set for whatever the future may hold. Fortunately, a painful-sounding accident a while back didn’t deter him.

He recalls, “About 15 years ago I took a fall, and put my hand out to break my fall, right onto some broken glass. It cut the nerves and tendons in my left hand. If I showed you my palm you would see the shape of the bottom of a bottle – a semicircle. I had two surgeries for that, and lots of rehab.

“The guys were awesome, they said ‘Go and get yourself well and we’ll pick it up from there’ so now I can only play with two fingers, the two on the outsides. The two middle fingers, I just keep out of the mix. I’ve learned how to do that. I’ve got flexibility straight up and down, so I can make a fist, but when I try and bend those fingers individually, they don’t bend.

“The surgeon was brilliant, but a couple of the tendons let loose, and I felt them when they did, so it was bad. But you know, you stick with it and you get around it. Thank God there’s only four strings on the damn thing. I never looked at it as ‘I’m never gonna play again’, I just took the attitude that I’ve just gotta get over this and get it done.”

On a more cheerful note, how does it feel to stand on stage with AC/DC, whose back catalog contains some of the world’s most loved songs, and blast them out to a stadium audience?

“It’s brilliant. It’s fantastic,” he says. “When we do a new record, we’re hard pressed to slot a song in from the new one, because the guys have written so many damn popular songs that people want to hear that we’d end up with a three-hour set if we weren’t careful. I know McCartney does it, God bless him, but it’s not like Angus running around. It’s been fantastic to see audiences react to those songs, it’s really heartwarming.”

So will we see Cliff back on stage with his band, virus permitting?

The guys have written so many damn popular songs that people want to hear that we’d end up with a three-hour set if we weren’t careful

“We want to. Earlier on this year [2020], we all got together and rehearsed for three weeks to see how it would be – and it was fabulous. The band was playing great and the conversation got around to ‘Is everyone up for playing some shows?’

“I said ‘I would love to play a few shows’ so everyone was like ‘Great! Let’s go home and get the guys to work on putting the shows together’, and then of course the world went on lockdown. We’re hoping that lifts, because we would love to play some shows.”

It would be sadly ironic, we suggest, if Williams came out of retirement only to be forced back into it by the pandemic. He laughs and says, “Ain’t that life? We’ll all get past this, and everyone can get on with their lives.” More power to him.

- AC/DC's Power Up is out now via Columbia.

Joel McIver was the Editor of Bass Player magazine from 2018 to 2022, having spent six years before that editing Bass Guitar magazine. A journalist with 25 years' experience in the music field, he's also the author of 35 books, a couple of bestsellers among them. He regularly appears on podcasts, radio and TV.