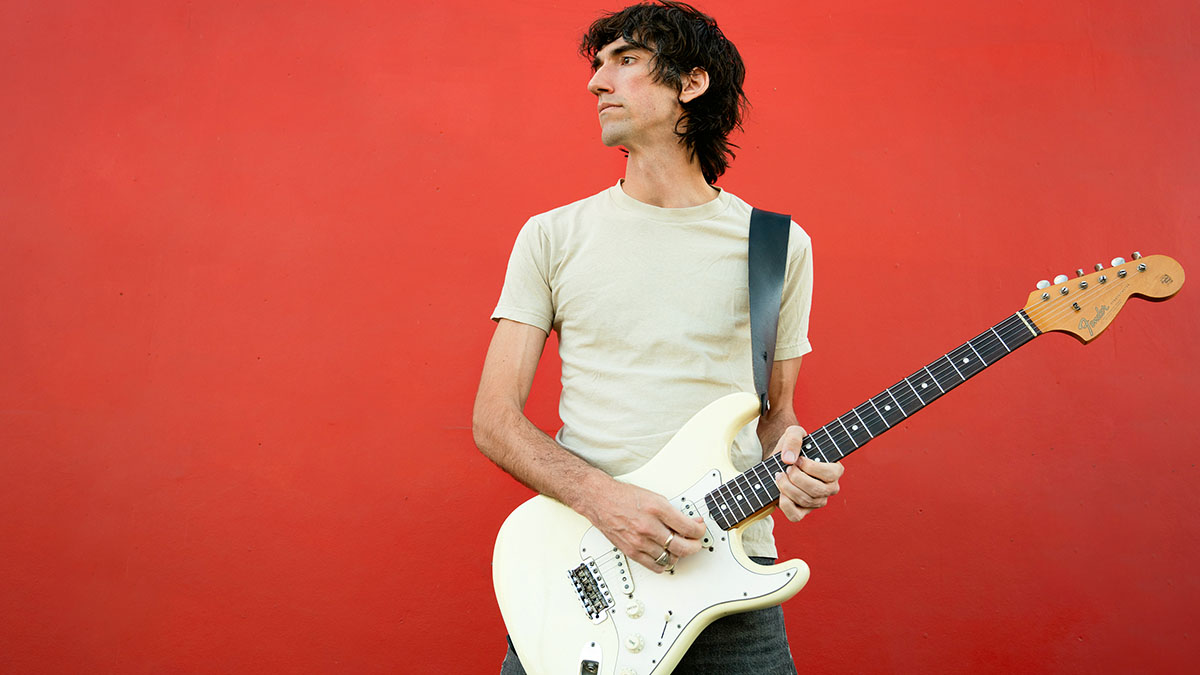

Delicate Steve: “The only technical advice I have discerned about playing guitar is that I like it to be really, really loud”

Inside the mind of indie music’s most unpredictable, and under-rated, guitarist

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

It is hard to think of another guitarist in the same lane as Delicate Steve (aka Steve Marion). He is one of the go-to indie sidemen, whose genuinely unique guitar talent has seen him play alongside the likes of the Black Keys, Amen Dunes, Mac DeMarco, Tame Impala and even Paul Simon. Yet it is his solo output that marks him out as a truly special player.

He has spent much of the decade that followed 2011 debut album Wondervisions making his guitar sound like anything but that. Instead he has used pedals and playing techniques – in particular, some vocal-like phrasing and innovative slide work – to create an evolving sound.

It is one that twists and turns across the space between those early electronic music synth and sampler experiments of the late-60s and the psychedelic indie of the mid-00s. If that seems like a wide range, it is. Marion does not like to be predictable.

For instance, 2017’s This Is Steve perfected the bright, bouncing approach he came to dub Cartoon Rock, while 2019’s Till I Burn Up was a bold (and successful) thought experiment in six-string electro-pop.

However, for his new record, After Hours, Marion has produced just about the last thing anyone would have expected: a record of unobscured guitar ’n’ amp jams, recorded with a small group of experienced and creative session players.

Unobscured by the tonal trickery of his previous records, you can hear a player whose character runs deeper than the window-dressing, with flashes of Mark Knopfler’s space, Keith Richards’ weaving, sketched melodic lines and Steve Cropper’s soulful note selection.

It is, he says, a sort of rebellion against the noise of 2022; the sound of Delicate Steve seeking – and finding – headspace. But if the psycho-social hokum doesn’t sway you, it is also an album of heady summer vibes strung together with some beautiful, soulful playing.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

We spoke to Marion about developing his individual playing style, the 1966 Strat that inspired After Hours and why, ultimately, it all revolves around seeking joy…

Until now you’ve spent a large chunk of your solo career trying to make the guitar sound distinctly un-guitar-like. These things don’t usually happen overnight, but was there a moment that put you on that path?

“Well, it really did happen overnight! It was a sea change for me, having been a teenager who played guitar and listened to Frank Zappa, Jimmy Page, Robert Fripp, Santana [etc]. I was a certified guitar player who could play all that stuff. I was in a band in high school that got a major record deal and the classic early ‘00s tragedy story where the record got shelved and the band broke up.

You could play like a high B note in a million different ways. You could play like Nina Simone would sing one note, or you could play it like Michael Jackson would sing it

“Then around 2007/8, in New York, all these really incredible bands [emerged] that made for a really interesting time for music. It was that free Spotify-era, pre-algorithm, when originality was not only celebrated, but was essential to stick out. Bands like Dirty Projectors, Ponytail – from Baltimore – and Deerhoof really influenced me.

“And all of these bands were making the guitar sound nothing like the guitar that I grew up trying to emulate. It was so refreshing to me. So when I made my first album, it was like a complete left turn for me, personally.

“People that found out about Delicate Steve might have thought I’ve been doing that my whole life, but it really wasn’t the case, so in a sense, this new record is me returning to an earlier state of development with my guitar playing, where I am more comfortable with the sound of the guitar being a guitar. I’m still playing it more like a singer, but I am not trying to change the sound of the guitar as much as I was on previous records.”

As you mention, your guitar style and, in particular your phrasing, is heavily influenced by singers like Sam Cooke. How does that translate into your technique? What does that look like on the fretboard?

“It’s funny to even think of it as ‘what it looks like on the fretboard’ because I’m not even seeing it, really. It’s definitely in my hands. Just to touch more on Sam Cooke and the vocal phrasing, it’s not just the way that singers sing certain phrases but it’s also that the most beautiful melodies are often the vocal melodies. Like Sleep Walk by Santo and Johnny.

“Most of the time it’s the vocals doing those extremely beautiful melodies. So it’s the phrasing I’m influenced by and it’s the melodies themselves and that’s a big part of the songwriting. And for somebody like Sam Cooke, there’s so much joy coming through. I really connect that with the sound and making the music. So it’s less really about all the other stuff for me, and more about getting to that feeling.”

Joyful melodies are often derided, as if only the preserve for manufactured pop music, but I suspect that it’s harder to write genuine, joyful music than sad or angry music.

“The way I would define a lot of my music, what moves me and compels me to make and finish a song, it’s this feeling. It’s like a sensory thing. That’s why the sounds and style of music I’m playing are almost completely irrelevant to me, so that’s why the music can come out in so many different ways.

“But something specific that influenced the framework for this record was, while I was in Arizona, I had a conversation with my friend Scott [McMicken] from the band Dr. Dog after I had covered Hallelujah by Leonard Cohen. He was like, ‘I heard that and it moved me to tears. It really made me understand what Delicate Steve is, which I think is less about the window dressing and all about the the phrasing.’

“Weirdly enough, I never thought of my own band in that way! So my last record [the electronic-focused Till I Burn Up], for instance, I did put a lot of conscious thought into the sounds that I wanted to be creating before making the record. But with After Hours, it was the first record where I said, ‘I’m not going to think about the window dressing of the sounds. I’m going to try to do this all on what is basically a clean electric guitar and really just connect with the phrasing side of things.’”

Is there anything that helped you develop your phrasing, outside of listening closely to vocalists?

“Well, for me, this tends to be really important and it’s the only technical advice I have discerned about how I like to play guitar is that I like my guitar to be really, really loud.

“I think that’s what gives me the sense dynamic range that I really like, and allows me to sound maybe bigger. If the guitar was lower of volume, I’d be playing harder, so instead it’s like putting it under a magnifying glass. It makes me just feel like way more connected to, to what I’m playing.”

Duane Allman is still one of my favorite guitar players of all time – he’s the reason I picked up a slide the first 50 times and instantly put it down because I couldn’t say play one note like him

In relation to the vocal style of yours – I’ve heard players talk similarly about being influenced by horn players – essentially emulating breathing in their playing and the spaces that leaves. It lends it this real humanity.

“Yes and, it’s so expressive, the guitar, too. You could play one note, you could play like a high B note in a million different ways. You could play like Nina Simone would sing one note, or you could play it like Michael Jackson would sing it. It’s not just like it’s on or off, like I’m picking it or I stop.

“You can put so much into the note. [When you start out] you’re just trying to make it sound like your influences, so it’s about getting out of that and thinking how you pick a note – like percussive, or soft, or with a vibrato at the end. Adding all those things can really make the guitar a different instrument, I think.”

I’m really intrigued by your slide playing. So much of the slide work we hear is tied strictly to blues and country. A song like Together [from 2017’s This Is Steve] sounds very distinct, in comparison. Where does that come from?

“The key singular influences on playing slide as a teenager were 95 per cent, Duane Allman, and five per cent of Mick Taylor on Exile on Main Street. That’s it. Duane Allman is still one of my favorite guitar players of all time – he completely transcends blues rock. So he’s the reason I picked up a slide the first 50 times and instantly put it down because I couldn’t say play one note like him, but I kept with it. So that was in my sort of pre-Delicate Steve phase of playing guitar.

I still don’t care about vintage guitars, but I do now have an appreciation for the sound

“Then I think when I just made my first record, I was just trying all these different techniques. One thing that stuck was mic'ing my electric guitar strings, then getting an amp sound in the room from that and mic'ing the amp.

“That’s a big part of my sound on so many of my records (though not the last two): getting that stringiness, which I just thought sounded really cool. Then the other key ingredient is not muting the strings with your other fingers, but really letting all of that brittle string noise come out. I think those are two big parts of my slide playing.”

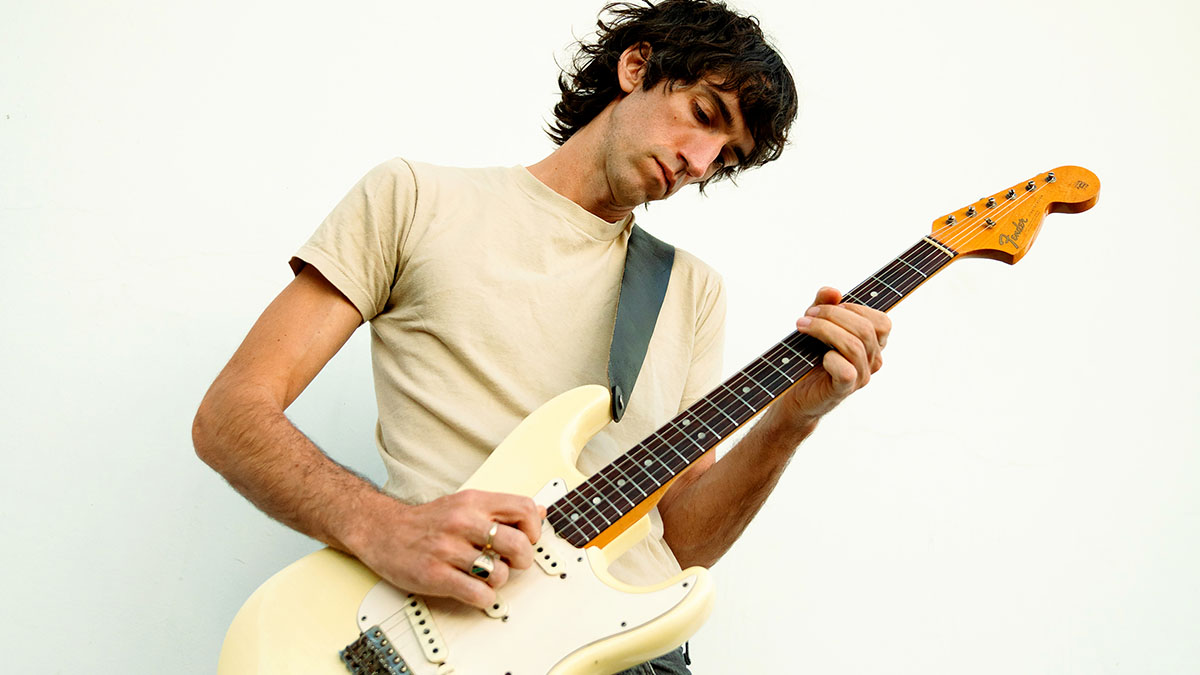

You’ve said this album was heavily inspired or influenced by your acquisition of a 1966 Stratocaster. How did that come into your life?

“Well, Keith Richards has a guy named Pierre, who is his guitar guy, and I’ve actually seen videos where it almost sounds like Keith Richards doesn’t even know what a pickup is and he’s like, ‘You’ll have to ask Pierre about this…’ My friend, Ofir, is like my Pierre. He’s owned more vintage electric guitars than anybody I know. He often just owns one for a couple months, really just to truly feel how it plays, and then sells it on.

“I asked him to find me a white vintage Strat, which he did and it’s been about a year of owning it. It feels like every week my relationship to it is evolving. I think I know how it sounds and I think I’m kind of playing it in the way I should be playing it but then it just keeps growing on me and kind of like unfolding in a way. And it’s like I still haven’t figured it out.

“I never cared about vintage gear – or any gear for that matter. I still don’t care about vintage guitars, but I do now have an appreciation for the sound. I plugged this into a friend’s vintage amp, and we compared it to her Strat, which was like an, incredible, new Strat from a custom builder and her guitar sounded phenomenal. So balanced and clean, so great. Then we plugged mine and right after and did the same thing and I could hear the difference in this crazy way.

“Mine didn’t sound better by any means. But it had so much more character and depth. So I love this thing and it’s been really fun just to just say look, ‘I’m not adding any pedals or sounds. So if I’m not connecting with what I’m playing, I’m going to either change the part or change the song.’ And that was really fun to just have the sound be pretty constant throughout the record.”

How dogmatic were you about that principle of just a guitar and an amp for your tones on After Hours?

“There’s a Strymon Blue Sky reverb pedal and maybe some kind of boost pedal on a couple songs and a Little Moog analogue delay on some stuff, but it was basically me and an amp and no pedals that colored the sound too much.

“We recorded in two different studios, and there were two or three amps in the rotation, but if this isn’t already apparent, I am not picky at all. When I’m trying to make a record, I just want to set up the mics and amp as quick as possible, because I write in the studio.

“So yeah, so it was a couple of different amps and I definitely liked this Beyer ribbon mic I was using and then it was mostly a small Fender Super Champ. I don’t remember the others but all three were small combos.”

I think for most Delicate Steve fans, a straight guitar ’n’ amp record made with session players backing is the last thing they’d expect from you. Why did you decide to do this now?

“First of all, if that’s really what Delicate Steve fans think then I’m happy. I love and respect and value artists that always catch me off guard. And it’s something I’m pretty conscious of, maybe to a fault! Truthfully, though, I’m just so sick of everything. There’s so much crap going on that the last thing I want to do as an artist right now is play dress up.

We’re so overstimulated right now that the only things that can break through are the most outrageous, or the most easily digestible

“We’re so overstimulated right now that the only things that can break through are the most outrageous, or the most easily digestible. Whether it’s memes that get shared with your friends, or sound bites and songs, there is nothing really that can break through in this kind of cultural climate that is sort of like lukewarm. But I actually think there’s a lot of value in that temperature!

“If we’re all just like monkey-brain-trained to pick the most obvious, easily digestible or outrageous thing all the time on our phones and in our lives, we’re not going to be attuned to things that just give us simple pleasure and are enjoyable.

“So that was in my thought process, and I thought: I’d be totally okay if I failed this way – if people don’t hear this record, because it gets lost in that sea of things. I’d rather have that happen than try to put on new shoes and compete with all of the impossible outrageousness that’s going on.”

What parts of the record stand out to you now, as a guitarist?

“For whatever reason, I’ve listened to this one more than anything else I’ve made – and I’m not up my own head! I’ve never listened to my music once the mastering is turned in – but this is like the opposite. I love the first half of the record. The song Playing in a Band – the sound, with the chords and the melody and the feeling of it.

“Then, on Looking Glass, in particular, I love the performances from the other musicians. That is probably a big reason why I’ve listened more to this record – there’s so much input from other musicians, as opposed to constructing everything myself.

Now I feel I can ride that guitar player lane. Or whatever that means to me, which is probably very different than the other artists in Guitar World!

“There’s percussion from Mauro Refosco, who’s played with Red Hot Chili Peppers, Atoms for Peace and David Byrne. Jake Sherman, the keyboard player who plays with Nick Hakim, and a bunch of other incredible artists, and Shahzad Ismaily, who played bass who plays with Marc Ribot.

“So I’m really listening to a lot of their parts when I listen to it, but I also just liked the guitar part that I made on that song. I don’t know what I was thinking, but I love it.”

What has making this record done for your relationship with the guitar?

“It’s definitely it’s made me feel more like a guitar player, in a way that I can stand behind, because I also identify as a sort of subversive pop artist and as a composer and a producer and as a songwriter – Delicate Steve is all those things to me.

“But previously, I think, in last place, was ‘I’m a guitar player’, even though obviously, that’s a big part of it. Making After Hours has brought it up pretty high in the rankings, I would say.

“Now I feel I can ride that guitar player lane. Or whatever that means to me, which is probably very different than the other artists in Guitar World! I don’t actually know what other guitar players are like, but I’m my own fantasy guitar player, I would say!”

- After Hours is out now via Anti.

Matt is Deputy Editor for GuitarWorld.com. Before that he spent 10 years as a freelance music journalist, interviewing artists for the likes of Total Guitar, Guitarist, Guitar World, MusicRadar, NME.com, DJ Mag and Electronic Sound. In 2020, he launched CreativeMoney.co.uk, which aims to share the ideas that make creative lifestyles more sustainable. He plays guitar, but should not be allowed near your delay pedals.