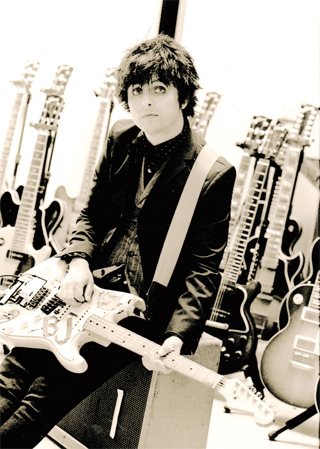

Green Day: Rebel Yell

Originally published in Guitar World, August 2009

Green Day's new rock opus, 21st Century Breakdown, fulfills the ambitious promise of American Idiot, singing a lament for troubled times. Guitar World talks with Billie Joe Armstrong about the making of the group's latest rebellious musical effort.

“I’m not fucking arou-ou-ond!”

Billie Joe Armstrong’s strident, angry voice comes tearing out of the speakers with an urgency that makes you feel like the man himself is about to rip through the grille cloth and personally throttle all the corporate criminals, talk radio creeps, hypocritical politicians and other greed-drunk oppressors who have reduced the United States of America, and indeed the entire world, to its present, sorry state. The song is called “Horseshoes and Handgrenades,” and it’s one of 18 glorious tracks from Green Day’s new album, 21st Century Breakdown.

The brilliant follow-up to 2005’s rock narrative tour-de-force American Idiot, 21st Century Breakdown traces the fortunes of a young couple, Christian and Gloria, as they try to make a life for themselves in an America where opportunities have become thin for the working and middle classes and the poor. But Armstrong stops short of calling 21st Century Breakdown a rock opera.

“There isn’t a linear story throughout the whole record,” he demurs. “I would say that what’s linear about the record is the music. I think the characters Christian and Gloria reflect something about the songs—the symbolism of two people trying to live in this era. So it isn’t all political; there are love songs in there, too.”

Seated on a leather sofa inside Studio 880—the Oakland, California, recording/rehearsal complex where much of 21st Century Breakdown was created—Armstrong doesn’t seem like the brawling, anarchist guerrilla progeny of Johnny Rotten who sings “Horseshoes and Handgrenades.” Trim, compact and sporting a pair of blue suede shoes, Green Day’s leader seems almost to retreat inside his own frame as he discusses the band’s new album, as if he were wary of taking up too much space, or feeling perhaps even a little sheepish at having unleashed the sprawling masterpiece that is 21st Century Breakdown on a world that seems on the brink of socio-economic collapse.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

But the album is just the tonic we need at this juncture: a bracing cocktail of rebel fury and the redemptive power of love, laced with just a tiny glint of hope for the future. For the past four years rock fans have been wondering if Green Day could top, or even equal, the quintuple-Platinum American Idiot. On 21st Century Breakdown they make that monumental task look easy.

“When you work that hard on a record and you see the rewards from it, you know that you made something you can be proud of,” Armstrong says of American Idiot. “And I think 21st Century Breakdown was us trying to rise on the shoulders of American Idiot and keep moving forward as songwriters. Going to new territory. But it takes a hell of a lot of patience to get to that.”

The creation of 21st Century Breakdown was a long process, beginning in January 2006 and ending in April 2009. Armstrong and his bandmates—bassist Mike Dirnt and drummer Tre Cool—worked on their own at first. Then they called in producer Butch Vig, the man behind Nirvana’s Nevermind, Smashing Pumpkins’ Siamese Dream and numerous other exemplary rock records.

Armstrong says, “The thing I liked about Butch is that he’s always followed his taste. He’s not the kind of person who goes for the money. It’s more like he was always recording for his peers. He has a lot of integrity, and I really respect him for that.”

Armstrong, Dirnt and Cool took a break midway through recording 21st Century Breakdown to kick out a quickie album of raucous, garage- and British Invasion–style rock and roll under the nom du disque the Foxboro Hot Tubs. The mid-Sixties sounds of the Kinks, the Who and Creation were also a huge influence on 21st Century Breakdown. But in Green Day’s widescreen rock opus, Armstrong tempers the infectious melodicism of these power pop forebears with the sweeping grandeur of Seventies classic rock and punk rock’s fuck-all belligerence. In short, he cherry picks all the best and brightest moments from rock history, harnessing their power to tell his tale of hardship and heartbreak here at the bleak dawn of a brand new century. Billie Joe manages to channel both Townshend and Lennon in the album's anthemc title track.

"My generation is zeo / I never made it as a working-class hero."

This ambitious invocation of the rock pantheon might not work so well were it not turbocharged by Green Day's combined musical muscle. Armstrong has dialed in his guitar attack with deadly precision. He can switch from punk's agitprop, barre-chord chop to classic rock's chiming, power chord clangor at the turn of an eight-note rest, piling on richly melodic leads in all the right places. 21st Century Breakdown is artfully layered with neatly stacked tracks of electric and acoustic guitar.

Meanwhile, Dirnt and Cool remain one of the most formidable rhythm sections in current rock. The bass lines are unassailably solid, yet admirably fleet-footed, while the drumming is a dizzying amalgam of manic energy and tight control. Crazed snare rolls take off as if chased by the Evil One himself, yet land squarely and miraculously on the downbeat each time. As musicians and songwriters, the trio have evolved steadily since those heady days of the mid-Nineties when they ignited the pop-punk explosion with albums like Dookie and Nimrod and now-classic tracks like “Welcome to Paradise,” “Basket Case” and “Good Riddance (Time of Your Life).”

No longer an icon of dysfunctional teenage rebellion, Armstrong, now in his late thirties, is wondering what kind of world his own sons, now entering adolescence, will inherit. 21st Century Breakdown is filled with ominous prognostications of the world to come, ripped from recent headlines: the environmental and governmental disaster that was Hurricane Katrina, the folly of the Iraq war, and an impending class war that undercuts the paranoid shriek of corporate media and the death throes of disaster capitalism.

But throughout the album, Armstrong tells his tale of recent world events in terms of their human cost and impact on our daily lives. “Last Night on Earth” is the love letter that every soldier in harm’s way wishes that he or she could write to a sweetheart back home. The album’s slashing first single, “Know Your Enemy,” could target any number of public figures. But instead Armstrong tells us that the ultimate enemy lies within—our own complacency, indifference or unwillingness to get involved and make the world a better place. So, when all is said and done, 21st Century Breakdown is a rallying cry for an inner revolution.

“For me, it’s about what I learned from punk rock,” Armstrong says, “which is sticking to your guns and trying to keep a spark of vitality alive. But it’s also about wanting to learn something new and not getting distracted by television addiction and trying to read between the lines of the lies that come at you. It says, ‘Rally up the demons of your soul’—just try to have a sense of urgency about yourself.”

GUITAR WORLD It seems that, whereas American Idiot was centered around the anger that a lot of people felt midway through the Bush administration’s reign, 21st Century Breakdown is centered around the problems that have come in the wake of that. Is that a fair contrast?

BILLIE JOE ARMSTRONG Yeah, it was almost like writing songs for the Depression era. And I do think the last record was more about rage and this one is more desperate sounding. But that was not intentional; it just started happening as the songs came together. I was just trying to photograph the moment for each one. And I wasn’t necessarily trying to be political. I mean, half the shit I write, I don’t even know what I’m writing about while I’m writing it. It just starts to come together.

GW Did you know from the outset that you were going to write another big rock opera/rock narrative album?

ARMSTRONG It was something that I knew I wanted to do in the future. I didn’t necessarily know that it was going to be the next Green Day album, but the album just started unfolding that way. I think the first song we wrote was “Mass Hysteria,” which is part of “American Eulogy.” Then “Know Your Enemy” came up a couple of songs later. So by that point you think, Okay, now I know where this is going, and you just start to follow the narrative, musically and lyrically.

GW A lot of the song structures are interesting. They’re not quite mini operas like some of the tracks on American Idiot, where you were combining five, six or seven different song fragments. But some of them, like “American Eulogy” and “21st Century Breakdown” seem like maybe two songs, or parts of songs, put together. Are you looking to get outside the normal, “three verses, a chorus and a bridge” song structure?

ARMSTRONG Yeah. I mean, I love British Invasion pop music—the Who, Creation and Beatles—and on to Cheap Trick…all that power pop kind of music. I love the two-and-a-half-minute single, and we’ve written plenty of songs in the past that have been in that “verse, chorus, verse, chorus, bridge, verse chorus” format. But right now, for me, it’s more about trying to mess with arrangements and make them unpredictable.

I wrote this song, “Before the Lobotomy,” that starts as an acoustic ballad and then turns into this completely different song. And then it goes back to the original acoustic ballad thing, but done in a gushing power chord way. I love messing with arrangements and seeing how they ebb and flow.

GW I think that’s one of the defining characteristics of this album.

ARMSTRONG Definitely. I had the song “21st Century Breakdown” as a demo version, just a four-track. And we had this whole other song “Class of 13,” with an Irish kind of part in it. Those were two completely different songs, and I just thought, You know, if I drop the key of “21st Century Breakdown” and I put it together with the “Class of 13,” that could really work. And I realized that that’s really what this whole record is about: breaking down a moment in time to try and make sense of it. And, literally, it’s like a nervous breakdown.

GW It’s also a societal breakdown. The breakdown of American society, really.

ARMSTRONG That’s what I mean, yeah. It’s pretty freaky what’s going on right now.

GW That’s for sure. The economy melting down…

ARMSTRONG Well, it’s a different crisis every week, you know? Especially since 2005. Natural disasters, the environment is fucked up, the automotive industry is taking a dive, there’s a financial crisis, economic bailouts, there’s two wars that we’re still fighting. And then we finally got rid of, thank God, the president and the administration that was pretty responsible for the shit that’s been going on. So there’s an anxiety about how everything has gotten fucked up in the past five to eight years. But there’s also this sense of hope, or maybe fear, of what’s going to happen in the future. Because the future is unwritten; it’s unclear. And I think a lot of that is reflected in the album. Especially when you come to the conclusion and a song like “See the Light.”

GW The lyric is “I just want to see the light” rather than “I see the light.” It’s as if you are wanting to be hopeful rather than being hopeful.

ARMSTRONG Right, right. “See the Light” is almost a call to arms spiritually. Something like “Know Your Enemy” is one kind of call to arms—a big, fat rebel song, definitely. But “See the Light” is a call to arms within yourself. As a songwriter, you’re trying to find the truth of every song that you’re writing. But when you’re actually doing the writing, you don’t know what that truth is. You don’t know what’s the big picture that you’re looking for. And with “See the Light,” I think the truth there is, “Oh fuck, yeah. I just want be happy!”

GW So after dragging us through this mire of misery…

ARMSTRONG Yeah, it took me a while to get to it. [laughs]

GW How did Butch Vig help in this process of find the truth of each song?

ARMSTRONG When we brought in Butch I think we were at the point where we were driving ourselves crazy. We’d done some writing and we’d reached the point where we said, “Okay, now it’s time to bring in an outside perspective.” When Butch came in, I just started throwing around ideas of how I wanted the record to be. And he threw in a couple of ideas. One thing we came up with was the phrase “rebel songs,” because, looking at the material, there are a lot of rebel songs. So things like that helped to start defining the album a little.

And Butch would also champion certain songs, like “Horseshoes and Handgrenades.” I’d kind of forgotten about that one. You lose perspective because you’re so close to the material and you start taking certain songs for granted. But Butch was like, “We’re recording that goddamn song!” And then I showed him the melody to “Restless Heart Syndrome.” As a songwriter, sometimes you start a song and put off finishing it. With that song I was like, “Oh, I’ll just wait and record that five years from now. I’m not ready for that song.” But Butch said, “No, no, no. You gotta chase down that melody now, and you gotta find the lyrics for it now.” So he was very encouraging.

GW How did Butch get selected to produce 21st Century Breakdown?

ARMSTRONG We met with only a couple of people. We met with Linda Perry. She was cool. She had some good advice and a good vibe about her, but maybe she wasn’t quite right for this particular project. I really liked her a lot, though. And we met Butch. I knew he was capable of making a great record. It was more about how we related to each other and if we liked each other, really, and I liked him immediately. He just brought a sense of calm and class. I didn’t always know what he was doing when he was tweaking out on things. He’s a very techie guy. He can geek out on something for a long time. But hearing the end result, I think we managed to hit a top end, a low end and an overall sonic quality that I don’t think we’ve ever achieved before. It’s bigger and more lush sounding.

GW So there’s been a parting of the ways with Green Day’s longtime producer, Rob Cavallo?

ARMSTRONG Yeah. He was going his way and we were going ours, and it wasn’t really making sense to work with him on this record. We’ve worked with him ever since Dookie, pretty much. I think we owed it to ourselves as artists to work with other people. I mean, I wouldn’t count out working with Rob again, but he just wasn’t the right guy with this record.

GW Earlier you mentioned your love for the British Invasion period in rock music. Name some songs that you think are the most perfectly built, perfectly constructed songs from that era.

ARMSTRONG Oh my God. [smacking himself in the face] Okay, I’m gonna say “Afternoon Tea” by the Kinks. And “Waterloo Sunset” by the Kinks. I’m kind of on a Kinks trip right now. I would say “Making Time” by Creation, “Pictures of Lily” by the Who, “19th Nervous Breakdown” by the Rolling Stones and “We Gotta Get Out of this Place” by the Animals. That’s just off the top of my head. Tomorrow I’ll think of five more and say, “Why didn’t I mention those?”

GW Have you been able to quantify the magic? What’s your take on what makes songs like that so incredible?

ARMSTRONG Well, I don’t sit around and do the math like [Weezer frontman] Rivers Cuomo or someone like that. It’s just one of those things where it raises the hair on your arms. I just love melody—that kind of melody, those guitar sounds and those song structures. And I love it as it’s written and played by those people. There was something about the way that those rock musicians in England were putting their take on American rock and roll and pop music. It’s almost like they just turned up the volume a little bit and it became bigger.

GW Do you see punk rock as an extension of that in some way?

ARMSTRONG Certain kinds of punk rock, like the Undertones, the Ramones, Generation X, Buzzcocks, and then bands of my era, like Operation Ivy, Crimpshrine, Jawbreaker and stuff like that. The similarity is that it’s all just really good songs written by authentic people.

GW Punk was a return to concise song structures after the prog and glam eras.

ARMSTRONG I think so. But some of that shit’s good, man! I put together a guilty-pleasure mix the other day, and one song was “Public Enemy #1” by Mötley Crüe. And I’ve gotten to like Poison a little bit more. I think their first album was actually pretty good.

GW I’m shocked.

ARMSTRONG No, no. “I Want Action”—that’s a good swing, man. It’s actually good. It’s hard to look at them, but I think there’s some good shit there.

GW And, as far as Seventies glam goes, you’ve certainly been influenced by Queen.

ARMSTRONG I think I like the idea of Queen more than I like Queen, ’cause I can’t sit there and name every song on A Night at the Opera. I like Freddie Mercury’s kind of grandiose style, and I like all the harmonies. Songs like “Killer Queen” are great. But I’m not a person who puts on a Queen record all the time.

GW Green Day have covered Queen’s “We Are the Champions” live.

ARMSTRONG Yeah. That started out when we were doing all these covers, and it was just fun to do. We did that and we also did “A Quick One” by the Who.

GW There’s a great tradition of British Invasion rock and power pop—three or four chords, a couple of verses, a couple of choruses. How do you go about putting your own stamp on that tradition and make it your own?

ARMSTRONG You just look for a melody to hit you over the head. You take your influences and try to sing your own song to them. It takes a long time and a lot of patience to wait for a melody to hit you, sometimes. Also, I’ve always had the loud guitars going—just a modern version of an old tradition.

GW So do you generally start with a melody when you write a song?

ARMSTRONG Yeah I do. I’ll get a melody in my head. Then I have to wait around for a lyric to hit me.

GW ’Cause some people strum chords and get their melody out of that.

ARMSTRONG Yeah, there are all different ways. I don’t have any formula in the way I do it. I learned how to play piano and I use that to write sometimes, whereas a song like “Know Your Enemy” was a guitar riff first. And then there’s a song like “¡Viva La Gloria!” which was definitely getting the melody first and putting chords to that, rather than putting a melody to chords.

GW There are a lot of piano-driven songs on this album. Are you writing more on piano these days?

ARMSTRONG Yeah. I don’t even know how to play it and sing at the same time yet, but the piano changed my writing a little bit. It leads you to different chord progressions and just kind of opens you up, because on a piano keyboard, everything’s laid out for you right there. So “Last Night on Earth,” “Restless Heart Syndrome” and “21 Guns” were all written on piano. The piano has added another dimension to where we’re at now.

GW At what point in the songwriting process did the characters start to emerge?

ARMSTRONG I’ve always loved the name Gloria. And Christian, that’s like St. Jimmy in American Idiot; Christian is a Christian name for sure. I think if there’s one positive character you could pull off of this record, it’s Gloria, because she’s the person who wants to carry the torch and declare her own independence and sense of worth in a punk rock way. And Christian, his torch is more about burning the place down: self-destructive. So there’s a yin-and-yang thing between the two. Also, I’m singing from personal experience through both of them. I just like to add names to give the characters some flesh and blood. I think, in a way, that makes it a little less self indulgent, a little less about me, so maybe people can have their own attachment.

GW Are the characters extensions or continuations of any of the characters in American Idiot?

ARMSTRONG No, not intentionally, just two brand-new people. But I always thought it would be cool if we could make a movie with Jesus of Suburbia, St. Jimmy, Whatsername, Gloria and Christian—like combining two records together.

GW So is 21st Century Breakdown a sequel to American Idiot?

ARMSTRONG No. No! I think the only thing the two would have in common is just the source they’re coming from, which is me, Mike and Tre. So there are bound to be some similarities.

GW Were you thinking about your kids in writing about the Class of 13? Were you wondering what kind of world your son, who will graduate high school in 2013, will inherit?

ARMSTRONG That’s where I got that from, yeah. 2013 is when Tre’s daughter will be graduating, as well. And I just thought, Wow, what an unfortunate year to graduate, but what a cool year, too. I wouldn’t mind wearing a T-shirt that says “Class of 13.” So I just started thinking about the generation zero, born under a bad sign. Maybe we’re all part of the Class of 13 right now. And it can also be, like, the name of the band that’s actually playing. Instead of Green Day, maybe we could call ourselves the Class of 13.

GW It also seems like you’re really going after religion on this album.

ARMSTRONG Almost like a fetish! [laughs]

GW What’s your beef? Have you been put off by the way some people use religion politically to manipulate people?

ARMSTRONG Yeah, that, and there are just some scary moments. You know, I believe there are people who really think Barack Obama is the Antichrist and we are entering end times. And it’s almost like they want to fulfill a prophecy. There’s no sense of thought that comes after that, no thought of making things better. It’s like, Why make things better when this is God’s way? It causes people to become complacent and do nothing. And that’s frightening. I write about what’s scary about that. What’s the difference between that and being a suicide bomber? Most wars are fought because of religion. And in this last election, it became so important to know what someone’s faith is. Why? I had no interest in the religion of whoever was going to become President of the United States. So I just tried to tackle the hypocrisy of that whole situation and to make some sense of it.

GW “East Jesus Nowhere,” I guess, centers on the poor souls who drank the Kool-Aid, the ones who buy into this whole thing.

ARMSTRONG Yeah. You know, it’s kind of scary.

GW And in the song “Before the Lobotomy,” I kind of read the lobotomy as the dumbing down of American culture over the past eight years.

ARMSTRONG No, not really. That wasn’t the intention. I got that title from a headline in the San Francisco Chronicle. The article was about a guy who’d written a book about how he’d gotten a lobotomy because his dad thought he was too hyperactive. He was a problem child, so his father made him get a lobotomy. So the title of the article was “Before the Lobotomy.” Or maybe that was the title of the book. I don’t remember now. And the song could be about the dumbing down of society, but it all comes from personal experience, you know! [laughs] Dumbing yourself with drugs and alcohol. Overdoing it.

GW The media itself can be an addiction, a damaging drug.

ARMSTRONG Oh, fuck yeah. Television is definitely a major distraction. That’s a big one for me. The song “The Static Age” is about how you’re just bombarded with information. You know, like they come up with new diseases to have, that you need to be medicated for. It’s like graffiti on the sky, a fucking billboard—like they’re taking away a chunk of the sky to sell me something. It just gets overwhelming, and the song is overwhelming.

GW That image of static is in a couple of the songs on the album. I also took it as a reference to right-wing hate radio, Fox Network… “the bottom feeders of hysteria,” as you sing in “American Eulogy.”

ARMSTRONG Um-hmm, but I think it comes from all angles. CNN is just as responsible for confusing people as Fox. My brother-in-law is a professional skater, and he always says, “Just live. Fuck all the bullshit and just live.” That’s a very simple thing to say, but there’s so much truth in it. Get past all the bullshit and the noises in your own head. Shit, in my head, it’s like having two radios on at the same time while you’re watching television. So the thing is just trying to turn the noise down and find power in silence.

GW It’s especially hard to do that in modern culture, with the internet, BlackBerries, iPhones…

ARMSTRONG Yeah, it’s weird. It seems like fewer kids want to be rock stars. They want to be the guy who invents the next YouTube or Twitter or something. It’s a strange time.

GWAmerican Idiot was a huge success. It put Green Day in a whole new league. So was there any anxiety over having to top that or equal that? Was it the 400-pound gorilla in the studio?

ARMSTRONG I think it was a little bit. We definitely felt that we set the bar high on American Idiot, and we wanted to set it even higher for the next record. We were arrogant enough to think we were gonna outdo American Idiot—and we were completely humbled by the process of trying. There’s pressure every time there’s a success like that. But what do you do with that pressure? Do you let it get the best of you, or do you use it as some kind of fuel?

GW How did the success of American Idiot change your life?

ARMSTRONG It made me more accepting that being a rock star is a good thing. We came from an era where “rock star” was the worst thing somebody could have been called.

GW Sure, punk was always very mistrustful of that.

ARMSTRONG Yeah, but I think we all became more accepting of the fact that this success is a great opportunity, so let’s have fun with it. It changed my life to where I had more fun than I’d ever had before. Back when Dookie became successful, I felt like we were still learning. I felt like, “Hold on, let me just learn a little bit more. Let me evolve!” The success was kind of overwhelming at that time, whereas this was years in the making. I felt like we’d earned the stature we came to have.

GW How do Mike and Tre support you when you’re striving to come up with songs? Ultimately, the pressure is on you as the songwriter. Is it better if they stay out of your way or if they goad you a little?

ARMSTRONG It’s a cross between the two. They stay out of my way until I complete my idea. Then they come in with their opinions after that. And they’re always there for me, all the time. That’s what’s great about them. Mike, Tre and I were hanging out with Lars from Metallica last night, and he was like, “Man, I can’t believe you guys are such good friends!” And I was like, “Well, that goes without saying. Isn’t it supposed to be like that?

GW That is the idealized image of a rock band, like the Beatles in A Hard Day’s Night.

ARMSTRONG Well…we don’t do cartwheels through the fields together, but we’ve just grown up together, literally. I’ve known Tre since he was 17, and I’ve known Mike since he was about 10.

GW Making this album was a long process, as you said. Was the Foxboro Hot Tubs album just a way to blow off some steam?

ARMSTRONG Aw, fuck yeah! That was just a shitload of alcohol and an eight-track tape recorder. We had this old Tascam from the Eighties with a reel-to-reel tape recorder inside the mixing board. We had all this vintage gear and we just started riffing. We went on tour for the album, drank way too much and just had a great time together. I think we needed that escape for a while to refuel us or bring us together a little bit more.

GW With American Idiot and 21st Century Breakdown you’ve written indictments against the Bush administration and some of the most compelling portraits of this time that we’re living through now. Yet, it seems to me that you’ve always consciously distanced yourself from being seen as any kind of rock star activist saint, like Bono for example.

ARMSTRONG Well, that guy’s got a gift for doing the things he does, and it’s amazing. But sometimes I think of myself as being a bit of a comedian, also. A guy like Bill Maher is able to be more powerful through his comedy and the things he says on his show because he’s coming from the standpoint of a person who is living in society. For me, it’s very important to be a part of society if I’m going to comment on it. And to not be isolated.

GW You have a great facility for capturing what it feels like to be earning only 20 or 30 thousand dollars a year and the company just cut the health benefits. There’s a realism there that wouldn’t be there, I think, if you were coming from a more “saintly” perspective.

ARMSTRONG Yeah, maybe it’s about representing the underdog. I don’t know. I still have the same friends that I’ve had my whole life. And I’ve always lived here in Oakland. For me, it’s very important to feel connected to that and to stay deeply rooted in it. Maybe it’s just coming from the working class. When you come from the working class, you’re always working class. Or at least you should be, or have a sensibility about it. That comes very naturally to me.

GW I read somewhere that you still go to Gilman Street, the Berkeley punk club where Green Day got started.

ARMSTRONG Yeah. I played there with Pinhead Gunpowder a year ago, which was the first time I’d played there since ’93 or so. But yeah, there are a few people over there that I’m connected to still. And it’s still going strong.

GW But can you step in the same river twice? I remember going back to CBGB in the Nineties, and it was like a tourist attraction.

ARMSTRONG But I think Gilman’s done a really good job of not becoming that. And I think that’s because it’s a collective of people. You can’t go buy a Gilman Street T-shirt at Hot Topic or Fred Segal or some place like that. Gilman is just a place that has deep values and beliefs. Being at a Gilman meeting, you feel like calling each other “comrade.” It’s a socialist way of looking at rock and roll music. It’s a community.

GW Speaking of being working class, you actually use the term “class war” in “American Eulogy.” That’s pretty strong. Is that what this is ultimately about?

ARMSTRONG No, no. I don’t think so. I just use harsh imagery to try to make a point or reach a conclusion. I use the English language against itself. [laughs] Or abuse the English language. But I don’t think we even know the definition of a class war, because it’s never really happened, not in America, anyway.

GW Another pretty strong line in “American Eulogy” is the one about the martyr who said, “It’s just a bunch of niggers throwing gas into the hysteria.”

ARMSTRONG That was written right around the time of Hurricane Katrina, and it’s a comment on how the response to Katrina was so indifferent to the suffering of the victims. So that could have been FEMA or George Bush saying that—the disconnect that he has with, I guess, anyone who didn’t go to Yale.

GW So here you’ve come out with another beautifully detailed, full-blown rock concept album in a world that’s increasingly just about download singles and short attention spans. Why do you do it?

ARMSTRONG Why do I do it? Because it’s art. It’s an art form. It’s just something that I feel I have to do. Something I’ve always wanted to do. I love great albums—anything from Revolver to Dark Side of the Moon to London Calling. I just like making records where the songs speak to each other and there are some singles on there too. I’ve got nothing against that. But I love the art of making albums.

GW Do you think you’ll continue to go in this direction? Will the next one be a concept album as well?

ARMSTRONG I’ll do it again, but I don’t know about the next one. Because I also love the approach that we have with the Foxboro Hot Tubs—just flailing and going for it. I’d love to maybe do something like record an album in China. Just take a weekend, have a bunch of songs and make a kick-ass punk record in China. There are all kinds of different ways to approach making an album. I can’t look at life all the time as a concept record. I’ll probably have to get outside of that for a while.

GW I was going to say, any fear of turning into Jethro Tull?

ARMSTRONG No. There’s no fear of that. [laughs] I don’t think you have to worry about that.