“I had been warned I might be shot immediately but I decided to do it anyway": The unstoppable Charlie Haden

One from the archive: Bass Player’s July 1991 profile of legendary jazz bassist Charlie Hayden

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Stepping to the microphone to introduce one of his compositions, Charlie Haden dedicates the song to the cause of freedom. A near-riot ensues, and the sound of the Ornette Coleman Quartet is almost drowned out by wild cheering. The next day, Haden is arrested and held by the secret police. After a harrowing night of interrogation, he is released and told to leave the country immediately.

The incident took place in 1971 in Portugal, ruled at the time by a fascist government determined to retain its colonies in Africa. Haden was on a 14-country tour of Europe with a Newport Jazz Festival package that included the Duke Ellington Orchestra, Miles Davis, Keith Jarrett, and others. Disturbed by the prospect of performing in a country with a repressive colonial regime, Charlie felt he had to act.

"I thought about refusing to play, but that would have put Ornette in an embarrassing position," he recalls, speaking slowly in a soft but firm voice. "I've been concerned all my life about human rights and racial equality. I knew I had to do something, so I asked Ornette if it would be all right to dedicate 'Song for Che' to the black liberation movements in Mozambique, Angola, and Guinea-Bissau. He said, 'Yes.' I had been warned I might be shot immediately on the stage, but I decided to do it anyway."

This courageous decision typifies Haden's remarkable career; his dedication to creative music has always been matched by an equally fierce commitment to the cause of human rights. "I never sat down and said, 'Well, I'm going to become politically involved,'" he explains. "I grew up in the Midwest and the South, and all around was evidence of racism. I felt the injustice, and I just followed my feelings and tried to tell people how I felt."

Haden also believes in equal musical opportunities. Although he is typecast as a jazz player, his allegiance is to creative music in all its forms. "I listen for honesty," he declares. "When I hear that and feel that, then I want to start playing." His credits bear him out, and Haden's huge, warm sound has graced recent recordings by artists as diverse as Rickie Lee Jones, Bruce Hornsby, David Sanborn, Paul Bley, and the astounding Cuban pianist Gonzalo Rubalcaba

Of all his outlets, though, the one closest to Haden's heart is the Liberation Music Orchestra. Conceived in the '60s as a vehicle for protest against the Vietnam War, the Orchestra is the grand passion of Hayden's musical life. Over a 22-year span, he has directed the making of three Liberation Music Orchestra albums, each featuring arrangements by Carla Bley and the personal statements of a diverse and accomplished group of soloists.

The albums have all been highly praised: both Liberation Music Orchestra (1969) and Ballad of The Fallen (1984) won numerous international awards, and Dream Keeper (1991), received a five-star rating in Down Beat mqgazine, where reviewer Art Lange called it "beautiful, inspiring music with a conscience and a soul."

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Another recent Haden project was Dialogues, a duet album with Portuguese guitar master Carlos Paredes. The recording traces its origins back to the 1971 incident that led to Haden's arrest: "After the government changed, I was invited to come back to Portugal for the 1978 Avante festival, an all-cultural event with artists from different countries. I played in front of an audience of 40,000 and when I came out onstage all these people started chanting 'Charlie! Charlie! Char-lie!' It was unbelievable.

"Later, I went to a club and played with Carlos Paredes. I knew immediately I wanted to record with him. It took 12 years, but we were finally able to get together in Paris in January 1990, with the help of Jean-Phillippe Allard of the French Polygram company. We had a rehearsal that was really funny, because there was no written music. I just listened to what Carlos was doing and tried to play along. I didn't feel very secure, but we went into the studio the next day.

"Every time we played something we'd rehearsed, he would completely change it. I thought I was really messing up, and after every take, Carlos would say something to his wife. I figured it was something like, 'Oh man, this gringo ain't making it. Get him out of here.' Finally I asked her, 'What did he say?' She said, 'He said that your bass makes his guitar deeper and that you are beautiful’. So I guess it wasn't that bad."

An understatement: The duets have remarkable clarity and depth, and the improvised exchanges crackle with energy. Learned by ear and spontaneously interpreted, the music also harks back to Charlie's childhood, when he sang folk tunes like "Old Joe Clark" and "Precious Jewel" on his family's radio show.

Haden was born in 1937 in Shenandoah, Iowa, where his parents settled after spending several years with the Grand Ole Opry. His father organized a family band that included Haden's sister and two brothers, and Charlie began to add vocal harmonies to the music when he was two. He continued in that role until he was 15, although he discovered another interest along the way.

"My brother Jim was the bass player on the show and I would sneak into his room and play his bass. I was only about ten, but I would try to play along with some of his jazz records. When I was in high school, we moved to Omaha and I met other musicians who were interested in jazz. I played bass in a group that performed for school assemblies, and I also remember going to a Jazz at the Philharmonic concert that featured Charlie Parker and Lester Young – I really loved that."

Haden's early bass inspirations were Wellman Braud of the Duke Ellington band and Walter Page with Count Basie. "They both had this big, gorgeous sound. You could almost feel their fingers gripping the strings and drawing out this deep sound. I loved the way their playing gave depth to everything and lifted the music up. Later on, I listened to Jimmy Blanton with Duke Ellington, and then to Oscar Pettiford and Wilbur Ware. Wilbur was always a favorite, because he had a way of making every note mean something."

While Haden was still in high school, his father retired and moved his family to Forsyth, Missouri. "I got a job playing on a TV show called The Ozark Jubilee," Charlie recalls. "The guitar player was Grady Martin – he and I would play jazz tunes during the breaks. On one of the shows, they had Eddy Arnold as a guest, and his guitarist was Hank Carland. We played together, and Hank encouraged me to get out of Missouri and try to become a jazz musician."

After saving up money from his day job as a shoe salesman, Haden took a Greyhound to Los Angeles. He enrolled at the Westlake College of Modern Music, but soon discovered that his most important training would take place outside the classroom.

“I was going to a lot of jam sessions and eating, breathing and living music every day. One night I was in a club and Red Mitchell strolled in. I introduced myself, and he said, 'Come by my house and we'll play.' I went over to his place one Sunday, he played piano and I played bass. Red told me he was working with [saxophonist] Art Pepper and said, 'You should come out to the club, because I'm recording and can't make the next week. Sit in with us – I know Art will like you.'

"So I went out, and they invited me up. I played some tune – I was so scared I still don't remember what it was – and afterwards Art asked me to work the next week. On my first night, the pianist was Sonny Clark; the next night, it was Hampton Hawes – so I was playing with great musicians right from the start. Eventually, I was working so much that I was cutting most of my classes. I decided I was wasting my tuition money, so I stopped going to school."

Soon after he dropped out of college, Haden met pianist Paul BIey, who hired him for a steady gig at the popular Club Hillcrest. "That's when I started meeting a lot of musicians. About that same time, Scott LaFaro came into town with [trumpeter] Chet Baker. He didn't have a place to stay, so I said he could share my apartment in Hollywood. We became really close friends."

The convergence of LaFaro and Haden was a remarkable event. In addition to being two of the brightest musical talents – on any instrument – of the late '50s, they represented two sharply contrasting approaches to the bass. Haden's playing is deep and solid, each line carefully pared down to its essentials. In LaFaro's hands, the instrument took on an entirely different character: his solos explored the upper reaches of the fingerboard, and even his accompanying lines were filled with explosive flurries and breathtaking dashes.

Yet, as Haden is quick to note, they shared much in common. "Scottie used to practice and practice, and I'd come home and find him sitting with his head in his hands, real sad. He'd say, 'What's wrong with me? I just can't play what I'm hearing: and I'd say, 'Welcome to the club, man.' Scottie had been a saxophonist before he became a bass player and he had a saxophone concept of the instrument. He was the first bass player to put that together, but he was never satisfied with what he was doing. I kept trying to reassure him, but I was feeling the same way, too."

LaFaro's search for a new style eventually led him to join the exploratory trio of pianist Bill Evans, with drummer Paul Motian (who became a frequent rhythm section partner of Haden's). LaFaro's work with Evans – especially the live recordings made at the Village Vanguard ten days before the 25-year-old bassist died in an automobile accident – assured his place in the jazz pantheon. Haden, although he heard the role of the bass much differently, was in pursuit of something even more elusive: an entirely new language of improvisation.

"I was hearing something and trying to execute it without knowing exactly what it was, as far as expressing it in words. Rather than just playing on the chord structure, I was hearing another inspiration, something coming from the entire composition. It had to do with creating a new chord structure for the song and not knowing what that chord structure was going to be. It was something spontaneous, something you made in the instant you played it. It was great to do that and make it work, but I had trouble trying it out with other musicians. People sometimes got really angry at me."

In 1957, a chance encounter with saxophonist Ornette Coleman proved to be the turning point in Haden's quest. "I was sitting in a club, and this guy came in to jam. He got out his horn and started playing, and suddenly the room lit up. I'd never heard anything like it." Shortly after that. Haden was introduced to Coleman during a break at the Hillcrest.

'”I said to him, 'I heard you play the other night, and it was really beautiful’. He said, 'Thanks. Not many people tell me that.' After the gig, we got into his little Studebaker and went to his apartment. There was music everywhere; he picked up a piece and put it on a music stand and said, 'Let's play this.' We started playing, and we played all night and all the next day."

With the addition of trumpeter Don Cherry and drummer Billy Higgins, the impromptu duo soon became the Ornette Coleman Quartet, a group that made music history on such cataclysmic late-'5Os recordings as The Shape Of Jazz To Come and Change Of The Century (and, in 1960, on the double-quartet album Free Jazz, which reunited Haden and LaFaro). In contrast to the vertical structures of bebop, Coleman's "harmolodic system" emphasized improvised melodies, and the players were free to go where their ears took them. Although the music was condemned by some as "chaotic", its freedom and lyricism captured the imagination of many gifted players – including Haden.

Liberated from conventional notions of improvisation, Charlie went on to fully explore his singular style in a variety of contexts. Over the past 30 years, his work has enhanced the performances and recordings of such master improvisers as guitarists Pat Metheny and John Scofield, pianists Keith Jarrett and Geri Allen, and saxophonists John Coltrane, Joe Henderson, Jan Garbarek, Dewey Redman, and Michael Brecker.

In addition to the Liberation Music Orchestra albums, his own projects have included albums by Quartet West – with saxophonist Ernie Watts, pianist Alan Broadbent, and either Billy Higgins or Larance Marable on drums-and several solo projects. When not the leader, Charlie is often a catalyst, bringing together notable musicians (as he did with Pat Metheny and Ornette Coleman on Song X) or exposing new talents such as Gonzalo Rubalcaba, whom he discovered in Cuba while playing at a festival with the Liberation Music Orchestra.

Haden's extraordinary talent has been acknowledged with dozens of awards. He has been the top vote-getter on acoustic bass for nine straight years in the Down Beat Critics' Poll, and he is one of five nominees for the prestigious 1992 Jazzpar, the only international jazz award.

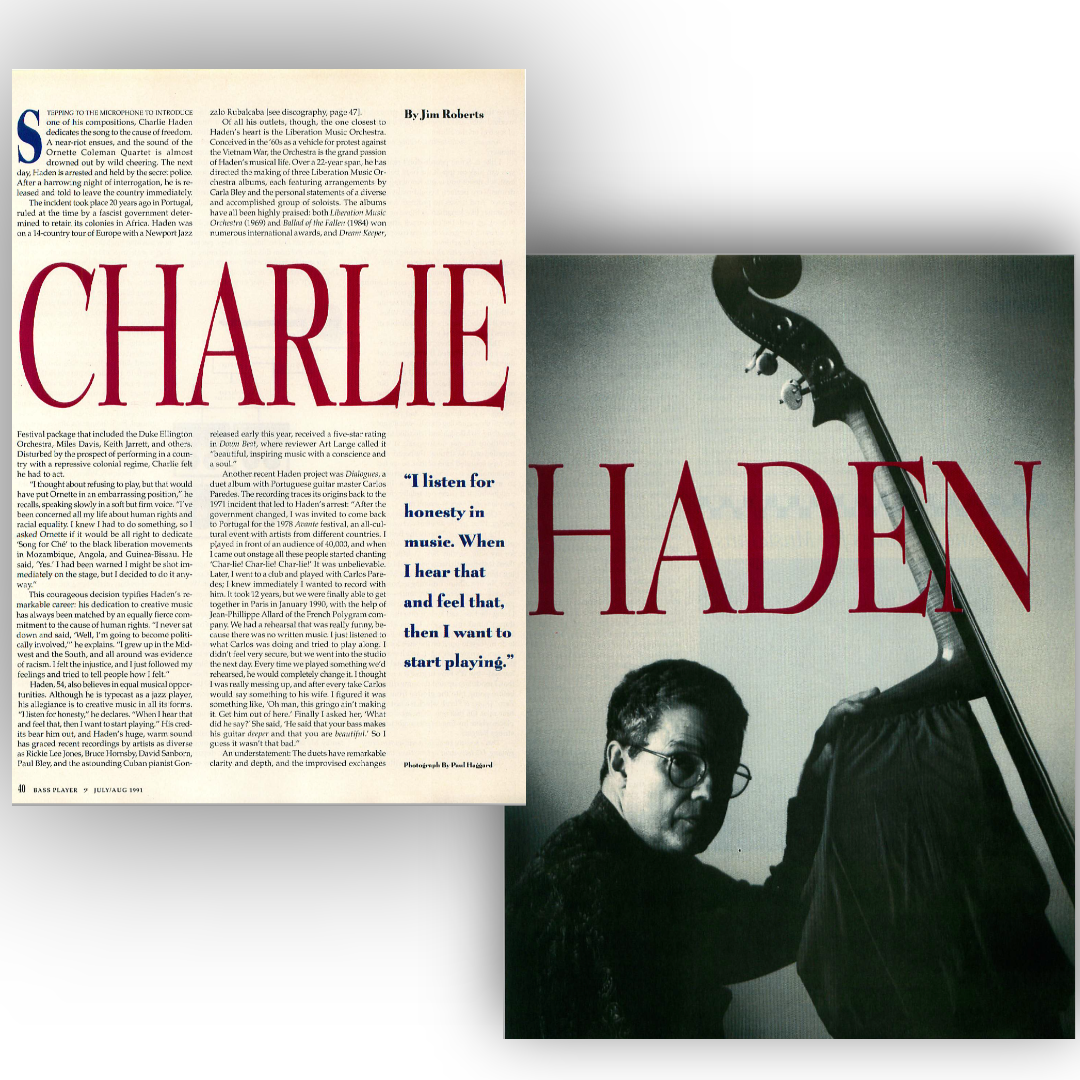

When he plays, Haden bows his head, closes his eyes, and sways back and forth with the currents of the music. (He closes his eyes, he says, because he once looked up at a New York gig to see Scott La Faro, Wilbur Ware, Percy Heath, Charles Mingus, Paul Chambers, and Ron Carter lined up at the bar, watching his hands.) Haden's tone is rich and woody, and his playing embraces many seeming paradoxes.

The movements of his left hand sometimes appear awkward, but his intonation is superb and he responds instantly to what he hears around him. He may seem to struggle to get out a single quarter-note; then he will unleash a Iong, fluid melody that arcs above the harmony. He has reverence for silence, yet his discography includes some of the most dense and dissonant music ever recorded. When he solos, Charlie often plays melodies that are childlike in their sweetness and simplicity, but his understanding of rhythm is highly sophisticated.

Above all else, Haden sings on his instrument, playing his carefully chosen notes with a warm, vocal quality that is instantly recognizable in any context.

Although his composing is not as celebrated as his playing, Haden has always written tunes for his own projects. For the last few years, he has been devoting more time to writing and, he says, “With all the work I’ve been doing, I’ve found that composing come much easier now.” Charlie’s latest tunes reflect his increasing fluency, and at least one piece seems to be on its way to becoming a standard: First Song which was written for Ruth Cameron, whom Haden credits for inspiring his recent creativity. (They were married on New Year's Eve, 1989.) Since being recorded on Quartet West's ["In Angel City in 1988, "First Song" has been covered by several other artists, including David Sanborn and vocalist Abbey Lincoln.

When he's not performing or composing, Haden spends much of his time teaching at the California Institute of the Arts, a Los Angeles school where he founded the jazz program in 1982. "My class is called Advanced Improvisation, but what I really do is try to show the musicians how to discover their voices. If you have music inside you, you just have to find out how to reach it and how to bring it to your instrument.

"There are so many different ways you can do that. One is to begin with complete silence and contemplate the state of your spiritual self. Then, when you begin to play, it's almost like walking into a cathedral. You can't do that without having humility and respect for beauty. The musician who is best able to make this happen is the one who says, 'Thank you for my gift, for what I've been given. I want to give this back.'"

Haden has also passed this message along to his four children. His son, Joshua, is an electric bassist, and the two share an interest in all forms of creative music. "Josh has already made two records on SST with his band, the Treacherous Jaywalkers. He's introduced me to a lot of great groups, and about five years ago I did a gig with the Liberation Music Orchestra opposite the Minutemen, with Mike Watt on bass. “There were all these kids with spike hairdos in the audience, and they loved the Orchestra. After both groups played, I was invited to jam with the Minutemen – it was a great experience."

Charlie's triplet daughters are also musicians: Tanya is a cellist, Rachel plays piano, and Petra is a violinist. "I've told them to always strive for the deepest sound they can get. You can get a deep sound out of any instrument, and when that sound comes back to you, it will inspire you to play even deeper. As I said, one of the best ways to do this is to begin with complete silence. When you start from silence, you're able to hear the timbre and the texture and the nuances of the music inside your soul."

Postscript: The Haden Triplets have collaborated with the likes of Foo Fighters, Queens of the Stone Age and Beck and in 2014 released a folk album produced by and featuring Ry Cooder on Jack White's Third Man Records. The follow-up The Family Songbook (2020) includes songs by Josh and their grandfather, Carl Haden Jr. Petra Haden plays violin, Tanya – who is married to actor Jack Black – plays cello and Rachel plays bass.Their brother Josh is the bassist and singer for the band Spain. They all appeared on Charlie Haden's 2008 album Rambling Boy, alongside Jack Black, Rosanne Cash, Elvis Costello, Vince Gill, Pat Metheny and more.

Charlie Haden died on 11 July, 2014, aged 76.

Jim Roberts was the founding editor of Bass Player and also served as the magazine’s

publisher and group publisher. He is the author of How The Fender Bass Changed The World

and American Basses: An Illustrated History & Player’s Guide, both published by Backbeat

Books/Hal Leonard.