Inside Dweezil Zappa's mission impossible: performing his father's Hot Rats album live

A half-century after the album’s original release, Zappa embarked on the ultimate labour of love when his Zappa Plays Zappa project planned to tour Hot Rats

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

There’s a good reason why you’ll never hear a covers band attempt Frank Zappa’s Hot Rats. It’s impossible. It’s unperformable. It’s unfathomable.

Even putting aside the art-rock icon’s leftfield electric guitar virtuosity, the 1969 album is a tapestry of overdubs and tape manipulation, a web of sonic subterfuge and obtuse one-offmanship, with makeshift ‘instruments’ that include a plastic comb and a mechanic’s wrench.

Given that even Zappa himself couldn’t recreate these tracks on the stage – what hope do mere mortals have? But that hasn’t stopped Dweezil Zappaaccepting the challenge.

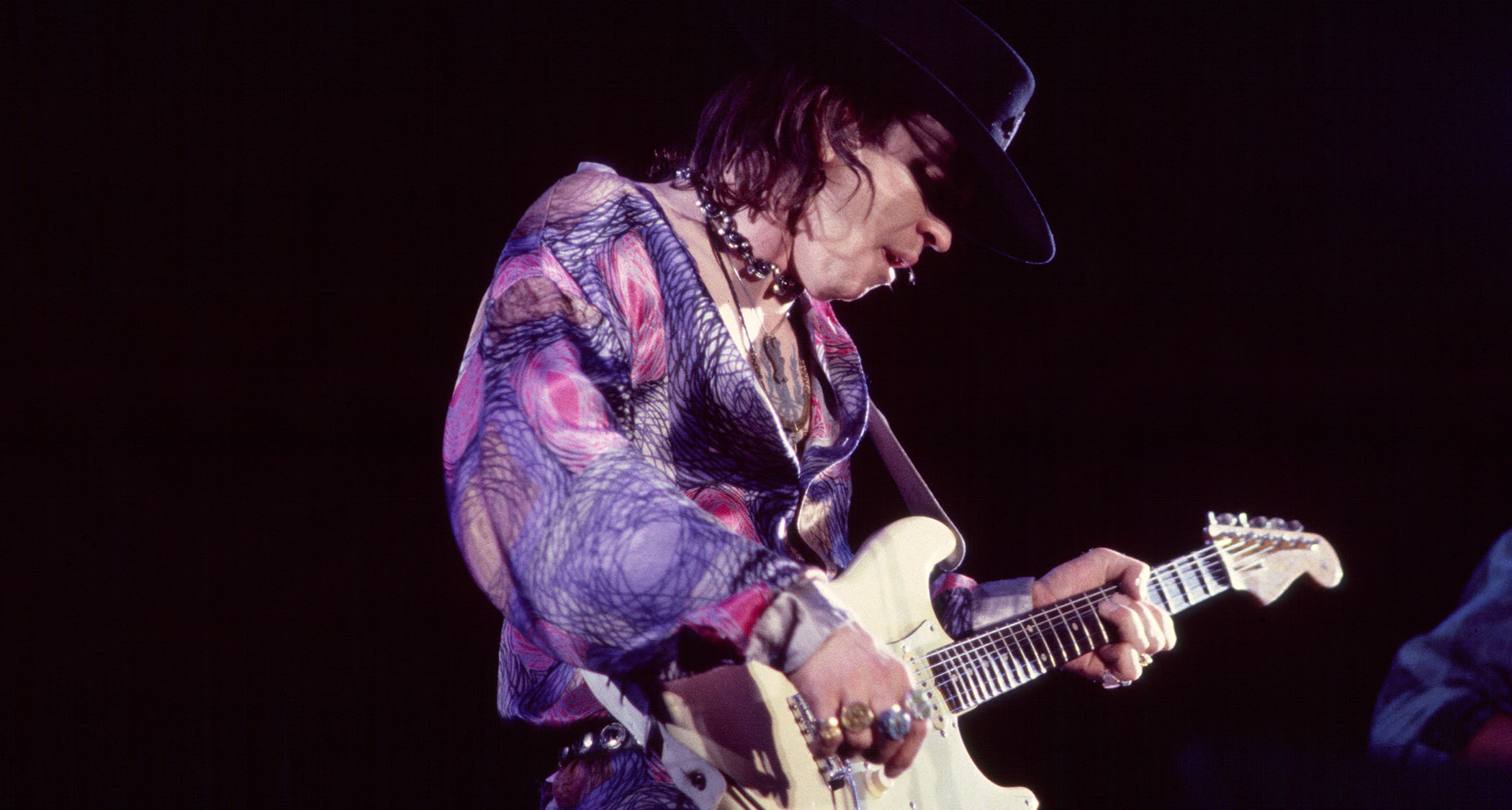

For the last 13 years, the fabled guitarist’s talented son has been the frontman and driving force behind Zappa Plays Zappa: a passion project that seeks to keep his late father’s music alive. Now, in a new chapter that has seen the guitarist slip between the roles of detective, genealogist and gear anorak, Dweezil has dissected every last element of Hot Rats – from signal flow to studio tricks – and he will present the results at seven UK dates in December, starting at London’s Royal Festival Hall.

“We want these shows to be like a time machine,” he says.

What made you want to bring Hot Rats to the stage?

“Well, it’s always been one of my favourites. I have a connection to that record that’s more than just musical, because it was made the year I was born and dedicated to me. To me, it’s one of the records that showcased my dad’s guitar playing in a new way. When you hear Hot Rats, compared to the early Mothers Of Invention stuff, there’s a different feel. It’s got a ton of attitude, y’know, songs like Willie The Pimp and The Gumbo Variations have some ripping guitar.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

"But then it’s got compositions like It Must Be A Camel, where you think, ‘How did he come up with this stuff?’ There’s a couple of songs he never played live, too, like Little Umbrellas and It Must Be A Camel. You won’t find live versions of those anywhere; they only exist on Hot Rats.”

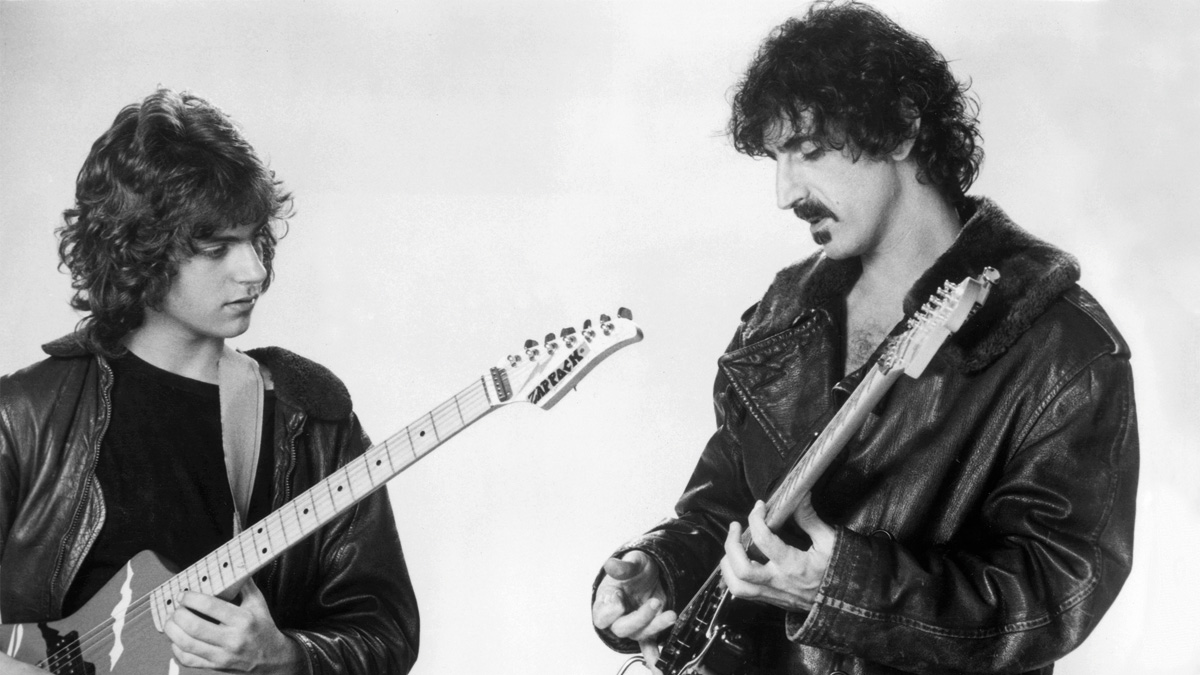

What stage was Frank’s career at in 1969?

“He was still in his 20s, moving towards more complicated music and getting musicians that could play this harder stuff – because the Mothers Of Invention guys couldn’t. He dropped the Mothers Of Invention name and he was out on his own. And what you’ll hear when you dive into Hot Rats – particularly on Little Umbrellas and It Must Be A Camel – is that it’s much more the work of a composer, as opposed to a pop songwriter.

"You’re hearing him really go deep into the compositional realm. The textures, the harmonies, the layers of instrumentation, the arranging, the way he manipulated instruments and changed their character: that’s what makes Hot Rats special. You won’t hear that on any other record of his – or any other record, for that matter.”

How did you approach the guitar parts?

“Well, I had to make a decision: how much of this record will I play note-for-note? Certain things were worth playing exactly the same. Like, obviously, the solo in Peaches En Regalia and Son Of Mr Green Genes, because that song is just so idiosyncratic. It’s my dad, doing what he does, and you’re not gonna top it. For others, like Willie The Pimp, I chose to learn a lot of the phrases but fill in the spaces between those guideposts with my own playing so I can also be free in my improvisation.

"But even when I’m playing freely, I’m still filtering what I play through his vocabulary. I know a lot of things that my dad would favour, the things that would be something he’d play. I didn’t want to take a big left-turn and suddenly think, ‘Oh, we’re in a totally different space.’”

Are there any signature techniques on the Hot Rats album?

“Well, one thing you hear him do a lot is mix up different versions of triplets. He’s got these really groovy pentatonic-bluesy runs where he’s squeezing triplets in places that most people wouldn’t think to do. And it’s because he started as a drummer. It’s almost like he’s got little rudiment-type articulations. It’s like sticking exercises or something – that have been attached to notes.”

How did you work out the guitar parts?

“I’d use a transcription software tool, which lets you slow things down but keep the pitch the same. The band is quite adept at reading – and I’m not, I do everything by ear. Then you learn it bit by bit and end up memorising it. The other process is, if there’s a composition that already has a transcription, we’d go through and check it against the recording to make sure they’re correct. There are transcriptions, even in published books, that have a lot of mistakes. So we check, double-check, triple-check.”

What are the challenges of recreating this music?

“One of the biggest challenges is the Hot Rats production. It’s a great-sounding album. People really appreciate it just on an audio level. So we wanted to make it evocative of the actual album and era. That’s almost as much work as learning the notes themselves.

“Sometimes it’s very difficult, if you don’t have access to the actual individual tracks, to decipher exactly what’s going on on this album. Especially with songs like Little Umbrellas and It Must Be A Camel. Because they had dense harmonies, layers of instruments, so many overdubs. And sometimes, for example, my dad would use a tape machine to extend the range of brass and woodwind instruments; he’d record them at a different speed so they’d play back at a higher register, and that’d totally change the timbre of the recording. Or he might have a really high-pitched snare.

"The guitar was actually recorded at normal speed. But on Peaches En Regalia, he recorded bass guitar at a different speed and he was tremolo picking it, so it ends up sounding like a synthesiser – well before most synths were made. If you were to just ignore those textures, it wouldn’t have the same flavour.”

My dad’s music was never fully discovered… My goal was to put the spotlight on his compositional skills, his arranging, his playing

Dweezil Zappa

Let’s talk about the guitar sounds on Hot Rats now…

“The real challenge was to recreate the lead guitar tones, to explore what my dad would have been using to make that unique fuzz tone with the clean tone blended in there. He had a kind of Frankenstein Goldtop he was playing at the time that had a Bigsby and a Telecaster pickup jammed in, so he had different out-of-phase options.

“At the time of Hot Rats, there weren’t many fuzz options out there, and he wasn’t yet using any of the Marshall or Orange amps. I think he was using Fender – it sounds like it was a Tweed amp – and he was combining fuzz stuff with the clean sound. So when you listen to Willie The Pimp, for example, there’s a fuzz tone that sounds to me like a Maestro, which has a Uni-Vibe on it that changes speeds, plus a wah-wah – I think he was using Vox at the time. But the wah is only going to the clean direct part, and it seemed like they were manipulating it after the fact, because the speed change of the Uni-Vibe and the wah are happening at the same time, and it would have required two feet to do it.”

Didn’t you inherit Frank’s Goldtop when he died?

“No, it was stolen. But for the Hot Rats tour, I’ll be playing a replica from the Gibson Custom Shop. Gibson made it about eight years ago, based on photographs of the guitar and all the specs I gave them. We made it as era-specific as we could, so it looks beat-up and it has the missing knobs. My dad’s Goldtop had P-90s, with that Tele pickup jammed in right next to the bridge.

”But as much as I love the sound of P-90s, I don’t love the noise that comes with them. So I basically have humbucking P-90s and a Tele pickup, all made by a Canadian guy called Tim McNelly. I can make them singlecoil with one switch, but I can also make them go out of phase in different ways. I have a piezo in there as well, so I can do the acoustic stuff that you hear on Peaches En Regalia. It’s a particularly heavy guitar – I haven’t weighed it, but it feels like at least 13lbs. I’m mostly used to playing an SG, so that Les Paul has really changed the way I play."

How did you recreate that very specific tone from Hot Rats?

“Well, the Fractal Axe-Fx is a great tool for me, particularly for stuff where you have to add a clean sound into a distorted sound. The Axe-Fx is great for that, because you can route different things to different outputs, and if I’m using four speakers in my rig, I can separate out the clean and dirty stuff, and actually blend them back together with volume pedals, and have control over the levels like at a mixing console.

"You can hear on certain parts of Willie The Pimp, for example, that the clean sound is louder than the distorted sound. My dad was just pushing up the fader forthe clean sound, but I can do that with my feet while I’m playing.

“It does take a lot of research to work out what the clean sound on Hot Rats would have been, though. It’s a direct sound, in some cases, that’s compressed, but it gets a bit of clipping from the console and tape machine. I recreate some of those saturation techniques, so it’s not just a pristine clean sound, it’s got a bit of edge.

When I set out, I wasn’t thinking, ‘I’ll do this for 20 years.’ But there’s enough music that it could keep going

"With the distortion stuff, I’ll also manipulate how hard the speaker is being run, because in the Fractal you have all this detail of how much saturation you want. I’m also using the Overstayer Master And Servant in my rig, acting like an analogue mastering section that’s adding some punch and saturation to the sound before it goes to the front of house. Even after that, when the front of house guy is mixing it, he’s using a tape machine plug-in to create even more of the layers, finding ways to blend in the old‑school quality of the sound.

“So we’ve gone to great lengths to recreate the signal flow that could have taken place during the recording. We want it to be like a time machine. We don’t want to modernise any of it.”

Will you be taking traditional amps on the road?

“No, I’ll just use the Fractal. Inside that, you’ve got every amp you could ever want. Typically, I’ll use Marshall and Fender [settings], but sometimes I use other boutique amps, like one by a Dutch company called Hook. With the Fractal, you can recreate things in incredible detail and store it in the presets.

“Another thing that’s made a big difference is, there’s a guy in Philadelphia who bought a lot of my dad’s old equipment. He bought the speaker cabs that my dad used in the 70s and these were Marshall cabs that had JBL speakers. A lot of people wouldn’t put those in their cabs because they’re more hi-fi, they have a broader frequency response, and for a certain kind of distortion they can be very bright or brittle – and a little stiff. But the way my dad ran his rigs, he was always looking for clarity in certain frequency ranges.

“Anyway, I was able to do some speaker IRs, y’know, some impulse responses with the actual cabs he used, and get it much more specifically dialled in. They’re built into the signal chain, just added into my speaker collection inside the Fractal.”

Do you think the Zappa Plays Zappa project has worked?

“Well, just the fact it’s existed for this length of time means there’s an appetite. When I set out, I wasn’t thinking, ‘I’ll do this for 20 years.’ But there’s enough music that it could keep going. The thing about my dad’s music is that it was never fully discovered. He had some songs that made it onto the radio and that would give people one singular impression of what he could do.

"But it gave the wrong impression. Things like Don’t Eat The Yellow Snow, Valley Girl, or even Cosmik Debris – some of these songs have a comedic narrative, and after his passing people started to consider him more like a novelty act. But it didn’t reflect the rest of what he really stood for. So my goal was to actually put the spotlight on the things he should have been known for – his compositional skills, his arranging, his guitar playing…”

Do you think working on this project has made you a better guitarist?

“Oh, for sure. I never would have been able to do the things I can currently do on guitar had I not taken a deep dive into learning this music. This stuff requires a lot of effort to learn. It’s very tough…”

Henry Yates is a freelance journalist who has written about music for titles including The Guardian, Telegraph, NME, Classic Rock, Guitarist, Total Guitar and Metal Hammer. He is the author of Walter Trout's official biography, Rescued From Reality, a talking head on Times Radio and an interviewer who has spoken to Brian May, Jimmy Page, Ozzy Osbourne, Ronnie Wood, Dave Grohl and many more. As a guitarist with three decades' experience, he mostly plays a Fender Telecaster and Gibson Les Paul.