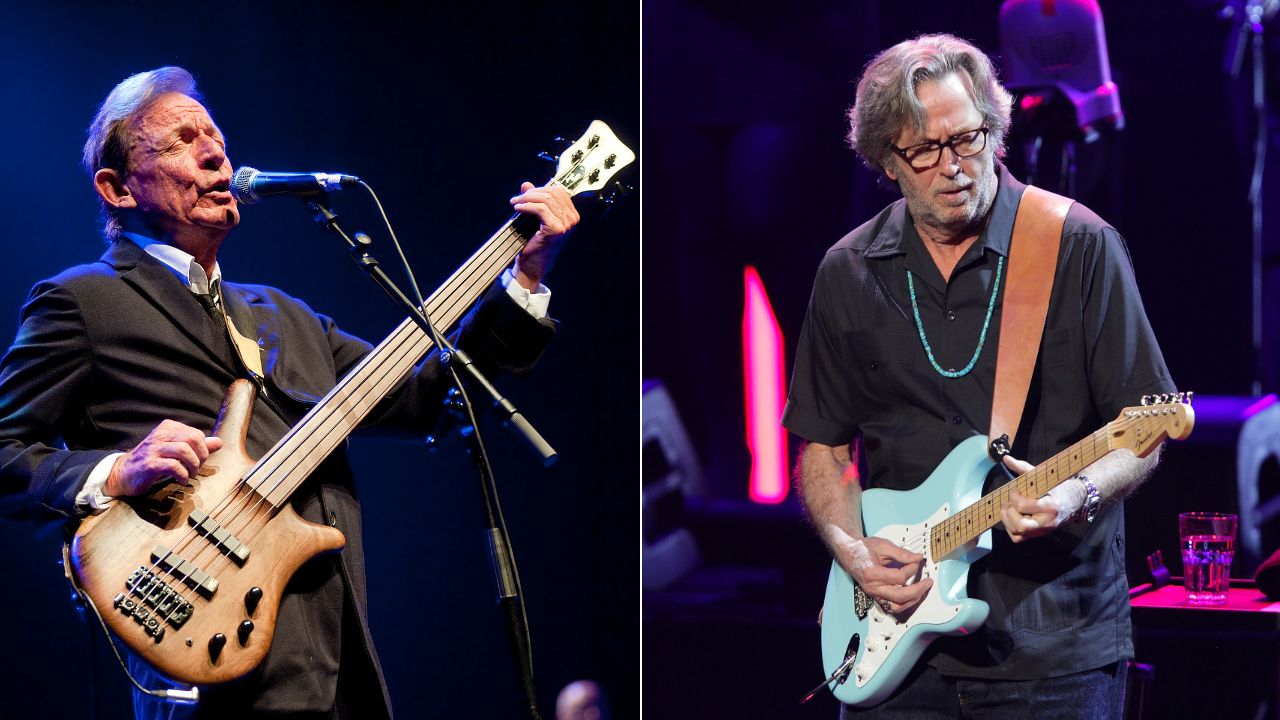

“Eric was a bit taken aback”: When Jack Bruce radically reworked Cream hits to Eric Clapton’s surprise – and that time Marvin Gaye asked him to join his band

Some people believe rock ’n’ roll should never leave the cozy three-chord confines of the garage – and then there’s Jack Bruce

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Some people believe rock ’n’ roll should never leave the cozy three-chord confines of the garage – and then there's Jack Bruce. The late Cream bassist, who died in September 2014, wouldn't have had it any other way.

“There are specialists who remain in one idiom for their entire careers, and no-one respects them more than I do,” Bruce told Bass Player in 2001. “But there also have to be artists willing to go out on a limb in order for the music to grow and go somewhere new.”

Ignited by the influence of James Jamerson, Bruce developed an aggressive, lead-bass style in the bands of blues rockers Alexis Korner, Graham Bond, and John Mayall. This culminated in the 1966 formation of Cream, the legendary power trio with Ginger Baker and Eric Clapton that permanently altered the face of rock.

Bruce's bass innovations – first with his Fender VI and then with his Gibson EB-3 – provided a cornerstone in the instrument's development.

In his post-Cream career, Bruce collaborated with artists as varied as Leslie West, Robin Trower, Frank Zappa, Lou Reed, Carla Bley, John McLaughlin, Bernie Worrell, and Billy Cobham. His solo albums comprise an audio diary of his unmistakable bass playing, singing and writing.

The following interview took place in New York City and was first published in the September 2001 issue of Bass Player, with Bruce promoting his 12th solo album, Shadows in the Air.

How did you get the concept for Shadows in the Air?

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“After a long solo-album hiatus – which was really just the result of me not having anything inspiring enough to record – I got the idea to do a trilogy of Latin-influenced albums. I must admit the crossover popularity of Latin artists plays a little part in it, but mainly I've just grown to love the music.

“I was a big fan of Chano Pozo's work with Dizzy Gillespie in the late '40s. Dizzy brought Afro-Cuban music to jazz, and in my own small way I'm trying to do that now by bringing it to rock – the same way Cream brought the blues to rock.”

The percussion on Sunshine of Your Love sounds like it's always been there.

“Right, like the song was written for this instrumentation – with percussion and Andy Gonzalez on upright – and this playing style. I wanted Eric to sing on this with me, so I figured he should bring his guitar along! We sang it just like the original, but now you can really hear the difference in our voices.”

White Room is more of a departure from the original.

“It was more of a challenge, too. The percussionists all worked their magic, and El Negro added some little ‘out’ beats that are absolutely ridiculous. Eric was a bit taken aback because there's no real backbeat except for me playing quarter-notes, but once he got into it he had no problem.”

How did your relationship with producer Kip Hanrahan figure in?

“We first hooked up in 1982 when he called me to sing on his album Desire Develops an Edge, and we've been working and writing together ever since.

“Kip and I had four other songs demoed for a total of six, which we brought to the core band: Milton Cardona, Changuito, and Richie Flores on percussion, Robby and El Negro on drums, and Vernon Reid on guitar. We culled the rest of the material from their input, suggestions, and improvisations. I was surprised that many of them knew my music, right down to the solo albums.

“We recorded the album during three weeks in New York – one week to cut the tracks, one week for overdubs and vocals, and one week for mixing. Eric Clapton and Gary Moore did their parts at Olympic Studios in London.”

Were you concerned about playing within the clave, considering your supporting cast?

“No. I'm not totally knowledgeable, but I've learned how to play and sing in the clave and to play a tumbao. On this album, though, it's about those guys coming over to my music and my bass playing. It's kind of like I paid my dues playing their music with them over the years, and now they’re reciprocating.

“I had some odd meters and other things they don't normally do, but they were bursting with ideas and enthusiasm. And incredibly, once we started playing, I never had to say a word or direct them – it just happened.”

The opener is a cover of your 1973 West, Bruce & Laing tune Out in the Fields.

“That was at Robby Ameen's request. We wanted to do a drum-n-bass-style take on it, though there's only a hint of that on the finished version. There are two tracks of bass; in the breakdown I add a second note in harmony with the original bass part. Actually, I recorded the basic track on piano. That's how I usually do it on my solo albums – all the way back to my first, Songs for a Tailor.”

“I usually cut with piano, drums, and maybe guitar, and I put the bass guitar on later, which is fun. Stevie Wonder let me look in on a session for an album he was making in the early '70s. He laid down an electric piano part and guide vocal, and then he overdubbed drums and then bass. That gave me ideas.”

What's the story behind Boston Ball Game 1967?

“I wrote that in Boston when I was with Cream, during the World Series between the Red Sox and the Cardinals. We were playing a club called the Psychedelic Supermarket and were holed up in a hotel.

“It was a difficult time for us to be on the street in a town like Boston because of the way we looked, so there was a lot of anger, which is reflected in the screaming vocals. I had always imagined the tune with horns, so instead of using it with Cream, I held it for Songs for a Tailor.

“It's a written arrangement done like the original, with the addition of percussion and Andy Gonzalez doubling my bassline while I gradually get loose with it.”

You've described its 6-against-4 feel as a Scottish version of African rhythms.

“I believe it's all tied together. The Scots have something called puirt à beul (pronounced porsht-a-bayle), which means ‘mouth music’ – people were so poor they didn't have instruments, so they invented dance music that was just clapping, stamping, and singing. And much like traditional African music, it goes between very heavy 12/8 or 6 to straight 8 or 4. I grew up with that.”

Dr. John plays keyboards on This Angel's a Liar and Windowless Rooms.

“I wrote those tunes with him in mind. I've admired Dr. John for many years, but we had never played together. He was great – the first thing he said was, ‘These songs are right up my alley.’ I also wanted to have material on the album that showed the relationship between Afro-Cuban and Afro-Caribbean music, and how it all came together in New Orleans.”

Both songs establish your ever-present connection to the blues.

“The blues is a great American expression of something that exists everywhere. I hear it in Indian music and African music. There's something called the Free Church Of Scotland which is so strict they're not allowed any musical instruments, so they only can sing – and you can hear it in there, too.”

How was Directions Home put together, with its multiple bass tracks?

“It was mainly improvised in the studio, as was Mr. Flesh and 52nd Street. All I had was the hand-clapped rhythm, which is the same clapped rhythm as Boston Ball Game played twice – but the second time it's pushed forward by an eighth-note. The percussionists were stunned when I first played it for them, but in seconds they were all over it.

“On bass, I played the chord roots with the band, and then I went back and overdubbed two more harmony lines and a lead-bass part that sort of decorates in between the vocals.

“Recording multiple bass parts is something I've done a lot over the years, inspired by Steve Swallow. I love the sound; I think of it as a sort of giant, warm acoustic guitar strumming away. I featured that approach on Childsong from my 1993 album, Something Els.”

You dedicate the track to Tony Williams and Larry Young of Lifetime. What are your thoughts on that band?

“Lifetime was, in many ways, a high spot for me. Cream was, too, of course – but you could say Lifetime was a later version of what Cream was doing. I was very proud to play with the late, great Tony Williams, and Larry was an absolute genius; one of the very few I've worked with. He's like the Coltrane of the organ. I'd have to say Lifetime was the most amazing band I was ever a part of.”

The album's three ballads are intriguing.

“I wrote Heart Quake with Pete Brown last year. It's in three with a minor tonality and long descending phrases. I cut the basic tracks with percussion while playing piano and singing a guide vocal, which we kept.

“I wrote Dark Heart with Kip; it goes back and forth between major and minor, and the percussion gives it more of a backbeat than a ballad feel. I'm quite pleased with the moving harmony in the bridge, too; that took a bit of work.

“Milonga, written with Kip, is the name of a popular Argentinean rhythm that's not as well known in the U.S. as the tango. The track is rubato, with me singing and playing piano and then overdubbing bass.”

Dancing on Air shows your R&-B/funk roots.

“The funk is just in my bones; I've always been naturally open to it. I attribute it to growing up in Glasgow, which is a lot like Detroit or Chicago, with its poverty and urban industrial setting – along with my early love of black music.

“I did a couple of TV shows with Marvin Gaye when he came to London in 1965. We hung out all night talking music, and he asked me to join his band, which I couldn't do, because I was getting married.

“I was getting a lot of criticism at the time for playing freely and melodically in pop and rock settings because of James Jamerson’s influence, so Marvin's approval meant a lot to me. Actually, Dancing on Air was on my 1980 album I've Always Wanted to Do This, but that was a more open version.”

Your remake of He the Richmond has a Jaco-with-Joni Mitchell vibe.

“People have told me that, and they've also mentioned Marvin's album What's Going On. I think the main reason – other than the melodic, filling approach I took with the bassline – is that I wrote it on acoustic guitar, which I play on the track using an open D tuning: DADF#AD.

“Before I was aware of Joni, I was very influenced by Richie Havens, whom we used to work opposite in Cream's early days. He showed me some of his open tunings, and it inspired me to write a few songs, including Rope Ladder to the Moon. For that I used an Em7 tuning he taught me, which is EBEGBD.”

Chris Jisi was Contributing Editor, Senior Contributing Editor, and Editor In Chief on Bass Player 1989-2018. He is the author of Brave New Bass, a compilation of interviews with bass players like Marcus Miller, Flea, Will Lee, Tony Levin, Jeff Berlin, Les Claypool and more, and The Fretless Bass, with insight from over 25 masters including Tony Levin, Marcus Miller, Gary Willis, Richard Bona, Jimmy Haslip, and Percy Jones.