Jackson Browne: "It took me a long time to understand what guitars I preferred – sometimes it’s the beat-up old one that works and the spectacular thing doesn’t"

The laureate of the '70s Laurel Canyon scene talks old guitars and the new directions on Downhill From Everywhere

Jackson Browne is one of America’s greatest singer-songwriters. His career took off in 1972 when he gave the Eagles their first Top 40 hit with his freewheeling ballad Take It Easy.

Going solo off the back of that success, he went on to record some of the defining albums of the '70s, including Late For The Sky and Running On Empty. Over the five decades of his career, two things have remained constant: a cool yet compassionate eye for the joys and tragedies of life, and superb songcraft.

Browne’s showing no sign of slowing down and his latest album, Downhill From Everywhere, takes on the big subjects of 2021, from the politics of hate to the decline of the natural world. The title of the record ushers us into its main themes, Jackson explains.

“Well, it comes from a remark or a quote by an oceanographer named Captain Charles Moore,” he says. “He’s the man who discovered the great swirling kind of plastic soup out of the North Pacific. And he basically just said that the ocean is downhill from everywhere. And I say that in the song – it’s really that the ocean is downhill from humanity and everything that humanity does.”

It’s an apt choice of title, because the album tries to address the gnawing sense that modern life is sliding towards a cliff-edge, driven by over-consumption and social division. The reason the music engages the listener’s heart, rather than just washing over you in a tide of angst, lies in Jackson’s gift for telling the human stories behind the headlines.

One of the album’s standout tracks, The Dreamer traces the story of a 12-year-old girl who crosses the border from Mexico to the US to reunite with her father. Determined to work for her place in a new land, she struggles to find her feet in an America where undocumented migrants are often exploited as cheap labour, yet despised as outsiders.

“I could never really get very far with the song until I met Eugene Rodriguez,” Browne recalls of its long gestation. “He’s got a youth centre for the children of immigrants in Richmond, California, and I met him through Linda Ronstadt and he works with musicians… he works with David Hidalgo and Ry Cooder, Taj Mahal. He teaches the kids the songs of their parents’ homeland and just teaches them where they come from in this great, great place.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

The immigrant community are the hardest-working people in America, they work harder than anybody – not just Latinos, but all kinds of people who have come to this country from other countries looking for a better life

“We were doing a song in the studio with David Hidalgo and I showed Eugene the beginnings of The Dreamer and he turned it into this story about a young girl coming to this country to join her father… I mean, the immigrant community are the hardest-working people in America, they work harder than anybody – not just Latinos, but all kinds of people who have come to this country from other countries looking for a better life. That’s what the whole country was founded on.”

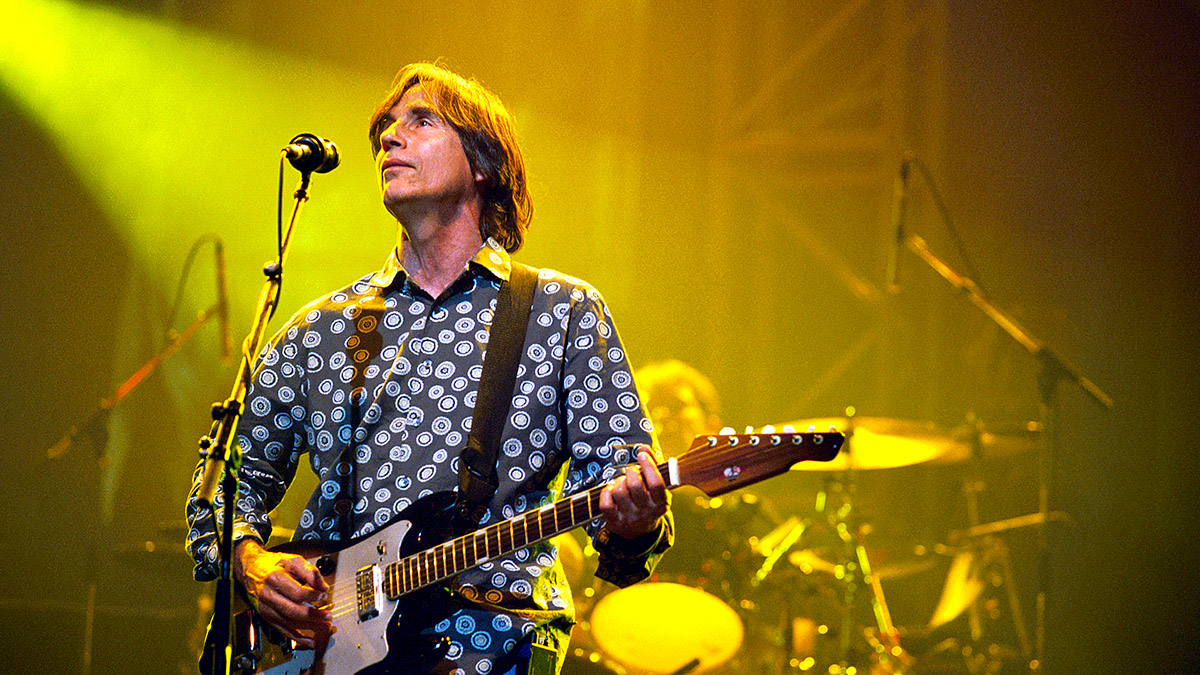

As well as characters that linger in the memory, the album is also filled with superb guitar work. Browne has enjoyed a lifelong love affair with six-strings, and his band features not one but two veteran sidemen who play off each other to deliver the album’s big hooks.

“In most cases, it’s Greg Leisz playing both slide and guitar, and Val McCallum playing electric guitar. On Downhill From Everywhere, it’s Greg on the left playing that backbone riff that just goes through the whole song – without that, there’s nothing to hang everything else on. So it was really a major breakthrough when he came up with that riff.

“We played that song for a long time and finally stripped everything away and just made it the most simple version… What Greg and Val do is they respond to each other and divide up the sonic territory between them in a very spontaneous way.”

Perfect Partscaster

Browne’s relied on a wide variety of guitars, vintage and modern, in the studio. But it was a humble partscaster that got the nod for some of the album’s biggest tracks.

“I played a Telecaster that’s tuned down a whole step on both Downhill From Everywhere and A Little Soon To Say. This is a guitar that was made beautifully out of parts and it’s one of the best guitars I have,” Browne says. “It was made for me by Scott Thurston, who played with me for a number of years and then was in the Heartbreakers.

“And he made a bunch of guitars at one point – and this one is just one of those magic guitars that’s got this incredible resonance. It’s got a great neck and body connection. I’ve also got this fascination for some of these beautiful Japanese guitars like Guyatones. I’m looking at a Guyatone that I have, right now as we speak, that I played on Until Justice Is Real.”

It’s not mere GAS that drives Browne’s interest in rare guitars, however. He likes to have plenty of characterful voices to choose from in order to find the best fit for the song.

“I got to say, I’m a real student of guitar tones… I’m always focused on trying to understand what they do, what it accomplishes. Sometimes you need a big distorted tone, or you think you do, but you go to use that and it sort of gets swallowed up by the other instruments. Like on Justice, it turned out to need a clean sound…

“I started listening to The Stones and realised how undistorted some of these guitar parts are, and how that supports the vocal and the drums. A good, hard, clean electric guitar tone will really help the vocal and the drums be heard. Anyway, it’s a continual mystery. I love guitars and love nothing more than just trying to fathom what they all do in terms of the tone and how they play.”

He’s also humble enough to embrace the fact that instruments impose their own agenda on the musician, as much as we may prefer to think that it is us calling the tune.

“Sometimes I pick up a guitar that’s famously played by some great musician. And I think, ‘Ah, I see: he plays that way because this guitar wants to be played that way.’ It’s really a big part, the guitar itself, a big part of what they choose to play. You just don’t play the same thing on whichever guitar you pick up. And guitars all have songs in them and because they want to be played differently; they make you play different things. And that’s why it’s a writing tool for me to have lots of guitars and different tunings around and to try to find out what each one sounds best doing.”

Early Guitars

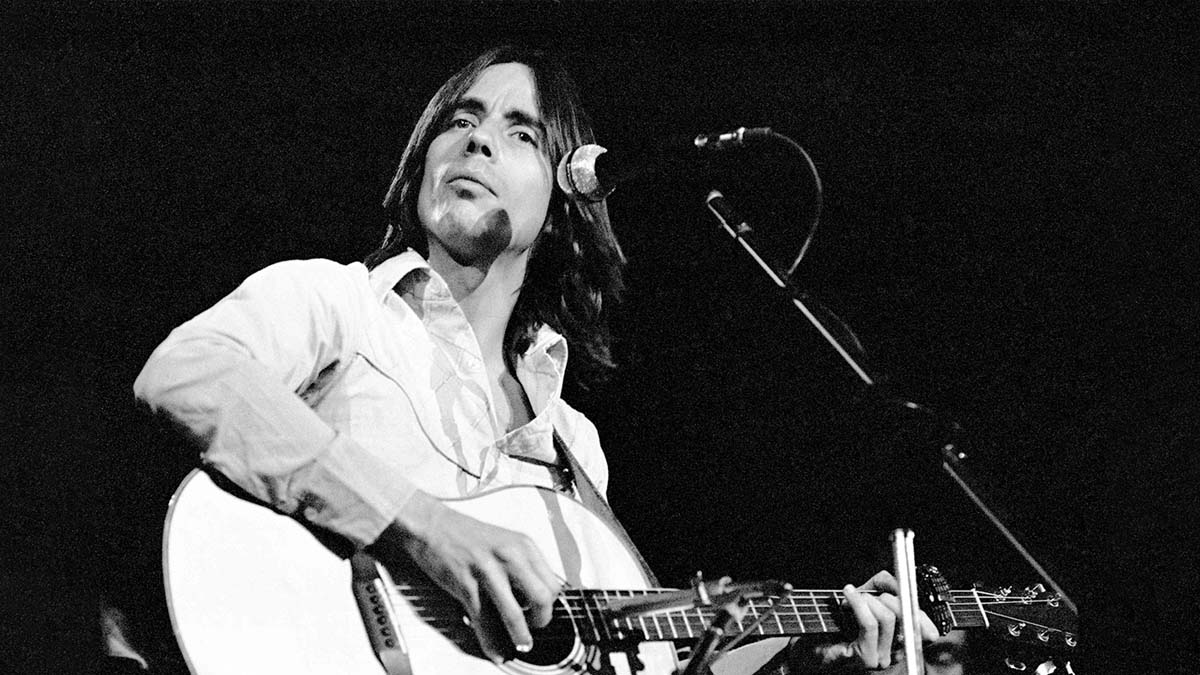

Browne’s long career with the guitar began, as so many do, with a budget acoustic in the family home. He says: “I borrowed my brother’s Kay acoustic guitar for a long time. I think I just sort of appropriated it. He moved to piano and he had this Kay guitar that wasn’t very good. But my friend had a Martin D-28 and I really wanted something like that. And so I think the first thing I bought was a D-18 when I was 16 and then I traded that for a J-200.

“And my father totally disapproved. He said, ‘Ohhhh…’ because I bought this big blonde J-200 that was flashy with all this inlay and gold, and he just looked at it like, ‘No, man…’ He just said, ‘I don’t think that was a good choice.’ But in the end, that J-200 and an electric I had got stolen from my house. A neighbour’s party sort of flowed into my house, you know, like over the backyard fence and somebody stole my blues collection, my records and everything.”

Following this disaster, Browne moved on to another famous American acoustic brand, picking up a Guild that became the mainstay of his classic '70s recordings. A Martin gifted to him around the same time proved less successful, however.

“After that I bought a guitar that I think was called a D-40, which was a Guild. I really loved that and it was a Dreadnought, too. I bought that from a friend and it was what I played on a lot of my first record. At one point, I was gifted a Martin D-45, but it just didn’t work for me. David Crosby had actually told my record company president, ‘Buy the kid a good guitar,’ and then he told them what to get [laughs]. So they just bought this guitar for me and I just never played it and eventually I sold it.

“Years later, I asked the guy I sold it to if he still had it and he just looked at me kind of quizzically like, ‘That? That guitar wasn’t any good.’ [Laughs] I don’t know… there was just a moment when everybody saw the D-45 as just the greatest guitar ever made or something and all these guys were using them. But they had exceptional guitars…”

Browne says that ornamentation doesn’t really do anything for him and he isn’t necessarily swayed by a famous name on the headstock, either, adding that his favourite guitar was produced by a relatively obscure New York maker – a special guitar that tragically met its demise at the hands of a ham-fisted repairman.

“It took me a long time to really understand what guitars do and what I preferred,” Browne reflects. “And sometimes it’s the beat-up old one that really works for you and the spectacular thing doesn’t… I just never really cared about [elaborate] inlay or anything like that. I just wanted a really nondescript guitar. And the guitar that I played right around the time I made my first album, that nobody else gravitated to in those days, was a Gurian.

“Michael Gurian [the New York luthier] stopped making guitars after a few years, but those guitars were really great. They were shaped like a classical but were deep and had a very rounded shape. They were beautiful guitars, huge-sounding guitars, and I had several of those.

“I still think about that guitar because it was ruined by a guy who I asked to figure out how to fit a pickup in it. I needed to play that guitar [on stage] and I told him to tape the pickup into the soundhole. But he cut the face of the guitar and mounted it that way and it ruined the tension of the top and after that the guitar kind of collapsed. I still pine for that guitar and it was like a disaster that it happened.”

Time has changed his opinion of Gibson’s J-200, however, and lately he’s found a place for a vintage example among his collection of studio guitars.

“I mentioned the J-200 got stolen before. Well, now I have one that I really love and it does a particular thing: I like it for an E tuning, and I played it on My Cleveland Heart... Actually, Val McCallum wrote My Cleveland Heart with me. I mean, he just gave me a demo of the music and I wrote the lyrics to it and some melody and some of that track was done on this great J-200.

“I always wanted to make that sound happen. But [after that song was written] he sold that guitar and we couldn’t get any other guitars that sound like that. So I said, ‘Well, who’d you sell it to? I’ll go to that person and get it back.’ But he said, ‘No, no, I can’t.

“I don’t know who that was, but I can show you to a site that’s got one,’ but it turns out to be like a ridiculously valuable guitar and I just couldn’t buy something for that amount of money just to record this one song. But instead I bought this J-200 that I have now.“

“And a couple of times I decided to sell it because it wasn’t really doing anything for me – it wasn’t as good as I thought it would be. But I’ve just used it a lot recently. Finally, I’m sort of earning it. And it was also expensive – though not as expensive as it might have been if it hadn’t at some point been refinished. It was probably a factory refinish, but nonetheless it’s not the original finish.

“Things can get really expensive in vintage guitars,” Browne adds, ruefully. “You know, it’s really great when you find one where something’s been done to it that makes it not as expensive as it would be if it were all-original. But there’s magic in old guitars – I also got really up on Roy Smeck guitars, a Gibson guitar that was made in the 30s as a Hawaiian lap steel acoustic guitar.

“There were people doing conversions to those guitars, so they played like a Spanish guitar. And the sound of that guitar really changed my world, changed everything. Also playing a really huge neck makes you play different things.”

Browne admits to being a prolific collector of guitars, but adds that there is a practical need behind it, centring on his love of alternative tunings.

“I have an advantage in having a crew that’s willing to haul this many guitars around for everybody. And I’ve got some guitars that will more or less work for everything. But they’re only really good for one or two things.

“I mean, you have to have some guitars that you’re willing to take on a trip or in the trunk of your car and be available. But there aren’t any guitars that you can play everything on. I mean, there’s some things that have to be done in a particular tuning and if I wrote a song in G, I don’t want to play it in F, you know? You play different things in D than you play in C. And that’s just the way it is.

“So I’ll usually tune the guitar so I can keep those [original] voicings. It’s a folky kind of approach, I suppose, using the open strings. Actually, I’ve got an electric guitar that just sounds amazing if I tune it one fret higher to F… I’ve got another guitar that’s tuned to Eb standard and a guitar tuned to F standard. It’s pathetic [laughs].

If you’re retuning a guitar from standard to, say, G or something it takes a while for the guitar to calm down and settle into that tuning... It's better if it’s sitting there ready to go

“But that’s why I wind up with 10 or more guitars when I do an acoustic show. But then again it does save time between songs when you might otherwise be retuning the guitar; I was never good at talking and tuning at the same time. And if you’re retuning a guitar from standard to, say, G or something it takes a while for the guitar to calm down and settle into that tuning.

“So it’s better if it’s sitting there ready to go. And that’s what I wanted when I played those acoustic shows by myself with that many guitars. It’s not just a shameless display of guitar wealth [laughs]. It also has a practical application, which is that I can just grab the guitar and play it.”

Indeed, Jackson has some of the spirit of a mad inventor when it comes to guitars. He gives a detailed account of his efforts to persuade a short-scale acoustic built for him by luthier Larry Pogreba to deliver a baritone sound before admitting that the concept only worked when he changed guitar completely and tried it on a Tele.

“I finally got the key and it turned out to be a Telecaster that I got to play that way,” he says. “And that’s holding up pretty well. So that guitar will now stay with these big strings on it, tuned low. And it just sits there: it’s solely to play that one song [laughs]. Sounds like a waste, doesn’t it? But it’s not – it’s like having some kind of special tool at the ready. I love guitars and I could talk about them forever. I mean, I’m such a voyager when it comes to guitars. I’ll try anything.”

- Jackson Browne’s new album, Downhill From Everywhere, is out now on Inside Recordings.

Jamie Dickson is Editor-in-Chief of Guitarist magazine, Britain's best-selling and longest-running monthly for guitar players. He started his career at the Daily Telegraph in London, where his first assignment was interviewing blue-eyed soul legend Robert Palmer, going on to become a full-time author on music, writing for benchmark references such as 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die and Dorling Kindersley's How To Play Guitar Step By Step. He joined Guitarist in 2011 and since then it has been his privilege to interview everyone from B.B. King to St. Vincent for Guitarist's readers, while sharing insights into scores of historic guitars, from Rory Gallagher's '61 Strat to the first Martin D-28 ever made.