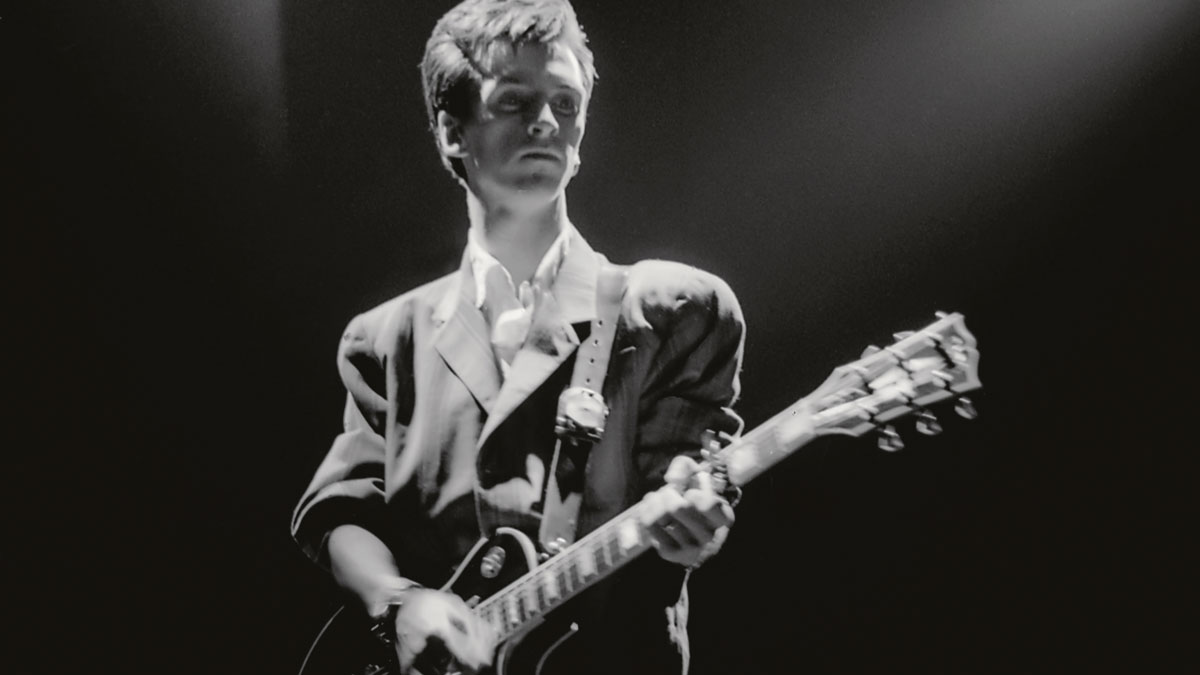

“Many people think I was doing it all on the Rickenbacker in the ’80s, but a lot of the clean arpeggio stuff was done on a Les Paul”: Johnny Marr on the most prized guitars in his collection – and why they might not be what you expect

From his bonkers nine-pickup Strat to the Les Paul he gifted to Noel Gallagher, The Smiths great has traced his entire career through the prism of his amazing collection of guitars. Why don’t all our guitar heroes do this?

Johnny Marr has long been known as “the man who would not solo”. But that’s kinda inaccurate, as Marr has soloed, sometimes in decidedly sing-song fashion, like on the Smiths’ Shoplifters of the World, for example. So maybe, Marr should be known as “the man who used crystal-clear arpeggios and interesting chord inversions rather than pulling off divebombs via big-ass amps” instead. Then again, legends via folklore aren’t born through literalism.

Anyway, as per the perpetual positive vibes slung Marr’s way, we can agree that he’s the proverbial king of the antiheroes – regardless of whether he solos. None of that has mattered to Marr, though, as he continues to craft landscape-defining indie music. But beyond that music, Marr’s life has been defined by utter devotion to all things six-string.

Marr is so intertwined with his now-massive collection of curios that he’s decided to celebrate them via Marr’s Guitars (HarperCollins, 2023), a 288-page book that reads more like a life story than an art project. To that end, Marr agrees.

“I’m glad it reads that way, because it’s basically my life story through the lens of photographing my guitars”, he says. “The original inspiration came through photo shoots with Pat Graham while he was working on a book called Instrument. I recognized his unique way of photographing guitars, which I found very beautiful.

“Pat takes these close-up, abstract shots that show a bit of rust on the bridge or a scuff on the neck, and I was fascinated by that. I originally wanted Marr’s Guitars to be full of abstract photos, but as more guitars were photographed, it evolved.”

If you’ve been following along with Marr, you’ll know he’s almost never without his trusty Fender Jaguar. It’s understandable, as he has done some incredible things with the guitar that figuratively and literally bears his signature.

When asked what drew him to the offset, Marr says, “The Jag, specifically my signature Jag, is a cross between a Gretsch and a Rickenbacker. And it plays like a Fender, but sonically, it’s like playing all three. It’s completely custom-made to sound like me. Like the Rickenbacker, the Jag made me play like me.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“When I picked up Isaac Brock’s [Modest Mouse] ’63 Jag while writing Dashboard, it was life-changing. And here I am still playing the Jag. I don’t even like guitar changes in my live set.”

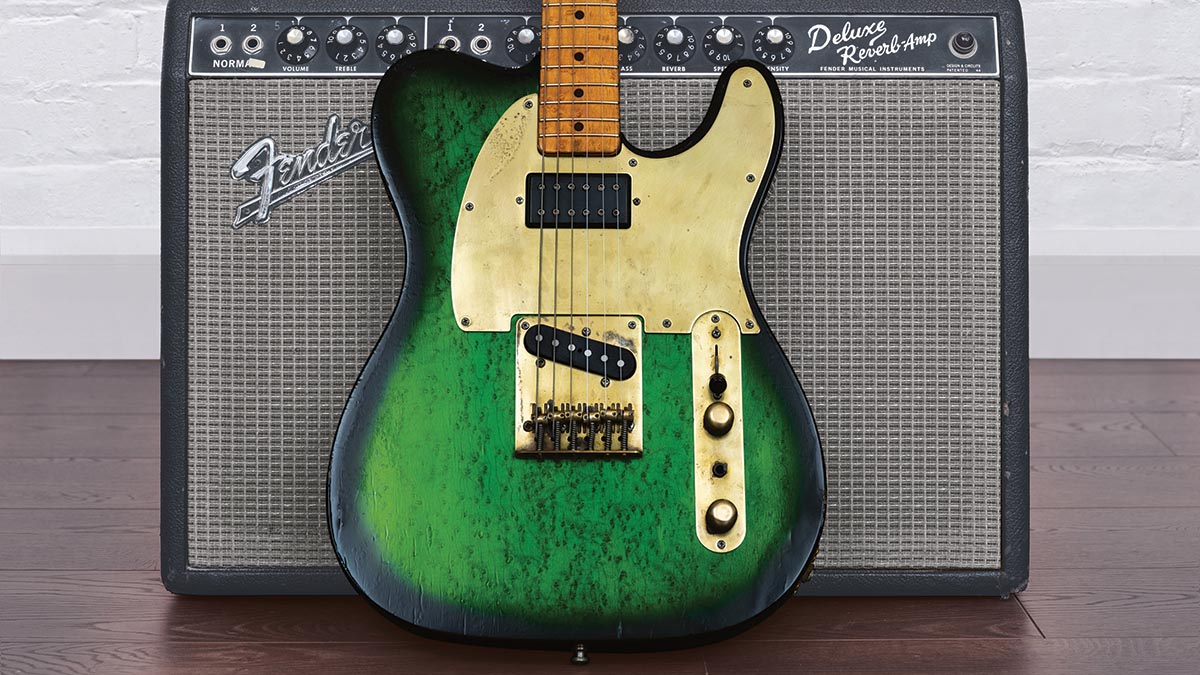

Putting together Marr’s Guitars has re-established Marr’s connection with many long-relegated axes in his extensive collection. “When I picked up my Epiphone Casino that I hadn’t played in 25 years, I was transported back to the last time I played it. When I grabbed my green Fender Tele I got in ’84, I remembered the clothes I wore when I got it. It’s hard to explain; guitar players will know what I’m talking about.

That “hard to explain” thing is precisely what Marr’s Guitars is about. Sure, Marr has a massive, covet-worthy collection of guitars, but if we step outside the grandeur and dig into the crux of the thing, undoubtedly, one can understand the relationship. More so than any other instrument, a guitar in hand can transport the player to a time when a literal millisecond defined a feeling.

“There’s tiny little messages you get from your brain when you put your hand on a neck,” Marr says. “You expect it to be slim, and it’s not. It’s like, ‘Oh, yeah, this is like a 1960 neck.’ Or you pick up a Tele, and you’re like, ‘I was expecting this to be much lighter,’ but you remember why it’s not.”

Marr smiles before adding, “And when you plug it in, you hear that sound and the nuances that make old, non-generic guitars different. The pickups are hand-wound, and human beings carved out the neck. You forget how individual guitars are and how they get that character – until you pick them up again.

“A vintage guitar isn’t rad because it’s old and cool,” he says. “It’s about the unusual things that – as soon as you grab it – make you say, ‘Okay, yeah, that’s right. I remember that about this guitar.’”

Tell me about how you came upon your Rickenbacker 330.

“I got it when the Smiths started taking off. It was the first ‘Does this mean I’ve made it?’ thing I got. Before that, I had been playing a Gretsch [Chet Atkins] Super Axe and constantly snapping strings because I was tuned up a whole step. I was forever snapping strings, and when the band got a deal, I got the Rickenbacker to be my backup guitar,’ but that changed because it was better than my ‘main guitar.’ [Laughs]”

Did you immediately know it was special?

“I knew it would make me play a certain way about chords and arpeggios. I knew the strength of the Smiths in those early years was the chord progressions I was using, and I didn’t want to do anything that reminded me – or anyone else – of pentatonic stuff.

“The Rickenbacker steered me in the harmonic direction of unusual arpeggios and chord changes. It was an excellent instinctive choice; I’ve had friends buy Rickenbackers, and they’re never as good as mine. It turns out that in the early ’80s, Rickenbacker made some particularly good guitars.”

I knew the strength of the Smiths in those early years was the chord progressions I was using, and I didn’t want to do anything that reminded me – or anyone else – of pentatonic stuff

Have you figured out why?

“I used to think it was the finish. But then Martin Kelly [musician, label boss] told me that John Hall took over Rickenbacker in ’84 and spent 18 months getting all the specifications improved.

“And it’s often said that ’86 is the vintage year, but I bought mine in ’84 when John Hall took over the company, and it’s been great. I’ve always had an instinct that those few years in the ’80s were particularly good, and I was right. Those were the comeback years for Rickenbacker.”

And how about the 12-string sunburst ES-335 used during the Strangeways, Here We Come sessions?

“At that point, I liked 12-string guitars, but like almost every other player on the planet, I learned that they took some application. I had been playing a Rickenbacker, and a 12-string was a hassle for an impatient guy like me, who was now working with some impatient tech.

“I had to get used to it, and it was a bitch keeping it in tune, especially those ’60s ones. But when I discovered the ES-335 12-string, I said, “Okay, let’s give this a go,” and it immediately clicked. It was a big guitar, but the humbuckers were dialed down and a little darker. That was the guitar I gave Bernard [Butler] from Suede, who remains the custodian of that guitar.”

Do you subscribe to the idea that we’re only temporary stewards of our guitars, as the best guitars will outlast us?

“That’s a lovely notion, and I agree with that, but that’s not why I’ve given guitars away. I gave them away because I’m close with people like Bernard, Noel [Gallagher] and [Radiohead’s] Ed [O’Brien], and I did it as a sign of respect. It was an act of sharing because I’m close to them.

“As you can see from the book, I’ve got a lot of guitars, so it was a way of letting go and letting my friends love them. But I will say the Oasis thing with Noel was different because in the very early days, they’d only played a few shows, and no-one knew they’d be so big. I just liked Noel and wanted to help him as he was just starting. When I was starting, I got a helping hand, and I wanted to help a fellow Mancunian, Irish fellow, so I gave him the Les Paul I wrote Panic on.”

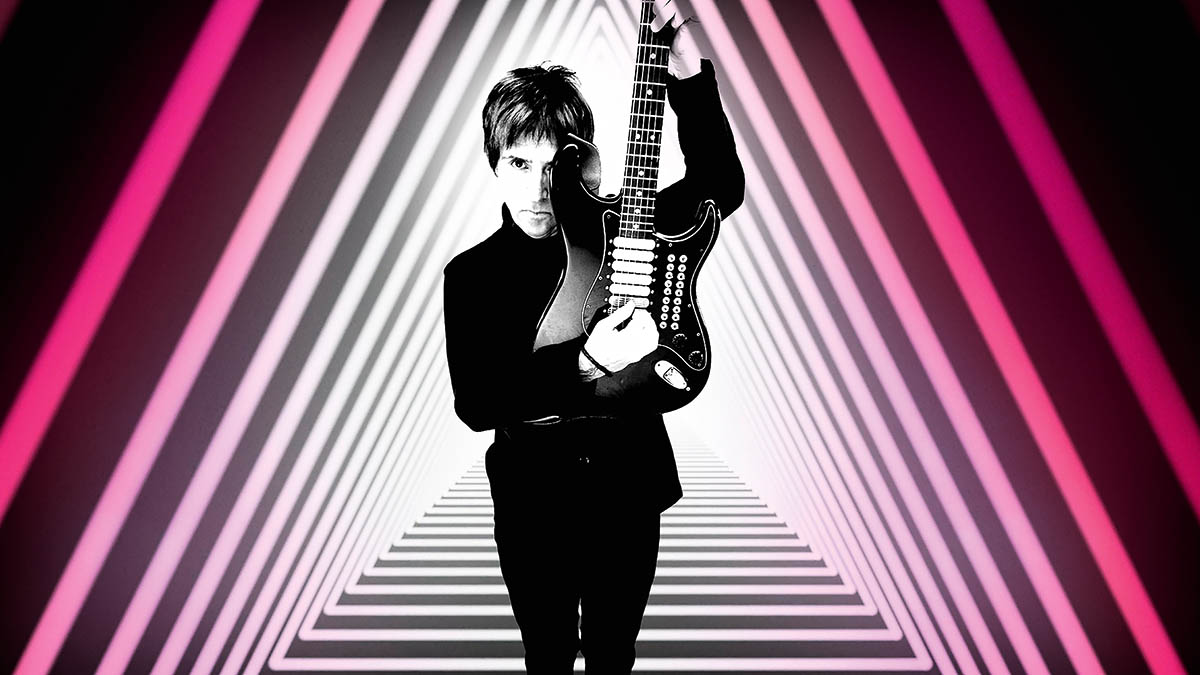

These days, you’re most often seen with your Fender Jaguar. Does it carry the same cache as some of the guitars you’ve had longer?

“Oh, there’s no competition when it comes to that. No guitar will ever come close to the Jag because I’ve played it exclusively for years. I’ve had these moments with the Jag, like doing the [James] Bond thing with Billie Eilish, the Inception thing, and playing Glastonbury.

“When I had 60,000 people singing There Is a Light That Never Goes Out back at me… I’ll never forget that because it was so brilliant. As for the older guitars, I became famous for using those through photographs from the ’80s, and they were close to me. But nothing comes close to the journey I’ve had with the Jag.”

Many people think I was doing it all on the Rickenbacker in the ’80s, but a lot of the clean arpeggio stuff was done on that Les Paul

Is there one guitar of yours that people don’t pay enough attention to?

“One guitar that people who have followed me probably know about but maybe don’t realize is such a big deal is my ’85 Gibson Les Paul. It’s the cherry red one I got when the Smiths were about to start recording Meat Is Murder.

“I got it to write on and used it a lot during that album. Before the Jag days, that Les Paul was on more records than any other guitar I owned. Many people think I was doing it all on the Rickenbacker in the ’80s, but a lot of the clean arpeggio stuff was done on that Les Paul.”

One oddball guitar I can recall is the nine-pickup Strat used in your Spirit, Power, and Soul video.

“Ah, yes. [Laughs] That was created by some crazy loon, who I imagine is somewhere in the north of England; they did that to a guitar. I got that Strat in the early ’90s, while I was out with a young Noel Gallagher.

“Back then, I used to drink, and when Noel and I went to a guitar shop after a long night out, I saw that guitar, and it made total sense to me. But the thing about that guitar is it sounds terrific! There are nine on/off switches and nine out-of-phase positions. She’s a guitar tech’s nightmare, but I used it on [2022’s] Fever Dreams Pts. 1-4, and I wrote Spirit, Power, and Soul on it.”

Are there any guitars or tones you’re still chasing?

“The answer is not in buying another guitar, only because I bought one a few days ago. But I am sort of working on a sound… I’m chasing a sound I hope to use on the next record. You can have all these things, like a Uni-Vibe; I can have that, but I’ll only ever sound like Jimi Hendrix, you know?

“As the years go by, it gets harder to do things that haven’t been done, and you end up sounding like yourself anyway. So there’s always a bit of chasing, but maybe the point of it all is adventure. I look around at all this tech, and I remind myself not to let it overtake me. I love adventure, but what I love most is the element of mystery that comes with it.”

- Marr's Guitars is out now via HarperCollins.

Andrew Daly is an iced-coffee-addicted, oddball Telecaster-playing, alfredo pasta-loving journalist from Long Island, NY, who, in addition to being a contributing writer for Guitar World, scribes for Bass Player, Guitar Player, Guitarist, and MusicRadar. Andrew has interviewed favorites like Ace Frehley, Johnny Marr, Vito Bratta, Bruce Kulick, Joe Perry, Brad Whitford, Tom Morello, Rich Robinson, and Paul Stanley, while his all-time favorite (rhythm player), Keith Richards, continues to elude him.

![B.B. King [left] cups his hands to his ear as he asks the crowd for more. Joe Bonamassa, with a Les Paul, gives his crowd a thumbs up](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/P3XrQLh86C27JfPp4AGp6n.jpg)