Knobs: “The function of pedals has changed – they're collaborative devices that don't have a fixed function. They're instruments in their own right”

In 2014, this YouTuber changed the pedal demo game. We get the lowdown on their creative process, the joys of collecting guitar pedals, and why music making is all about intent

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In November 2014, an unknown YouTuber posted a demo of the Death By Audio Reverberation Machine, with the caption “Chestnuts, owls, reverb. Everyone's invited to thanksgiving.”

A month later, a demo of the Montreal Assembly Count to Five followed, cross-posted to Reddit with the caption, "Just the neatest guitar pedal. Just so neat." It exploded, going viral in the guitar community.

That YouTuber was called Knobs. Their visuals and music would redefine not only the pedal demo, but also the way that guitarists talk about pedals. Knobs' strong visual style, eccentric sense of humor and abstract, effervescent guitar playing was completely unlike any other demos or media related to guitars or pedals available at that time. Since, they've been praised, obsessed over, parodied, and relentlessly copied.

Article continues belowTheir influence has been felt everywhere that there are guitar pedals. The way that people arrange pedals for an Instagram photo. The way people make videos, from this magazine to That Pedal Show. Even simply in the way that players explore and document obscure functions of their favorite pedals.

In 2018, Knobs paired up with their friends at Chase Bliss Audio to work as product designer for the Blooper, a next-generation looper concept. Working in conjunction with a team of programmers and engineers, they spent a year prototyping before presenting a public alpha at Winter NAMM in 2019.

Taking onboard feedback from players and industry friends, they then kickstarted it, blowing through their targets and raising $170,000 in the first 24 hours alone.

In 2019, Knobs again turned to Kickstarter, successfully funding Pedal Crush, a book written with collaborator Kim Bjørn. Featuring interviews with most of the key builders in the boutique pedal space as well as a lead interview with Steve Vai himself, it's become the go-to reference for modern pedals.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Over the years, the format of the Knobs videos has changed, with modular synths making an appearance alongside the guitar. Moreover, there was the sense that, as more people started emulating the original Knobs formula, it was time for a change.

Now, Knobs has shaken up their video structure completely, moving decisively away from demos. The new longer, monthly format will focus not just on pedals or modular, but any number of creative topics in a magazine-style format.

The only thing that links all these projects is a creative restlessness, paired with a desire to not be prescriptive, about either the guitar, or where their creativity will take them.

Guitar World sat down with Knobs to find out more about this journey. Why did their videos resonate so strongly with such a large audience of guitarists? How does Knobs view the guitar, and what is it they find so inspiring about pedals anyway?

I'm still uncomfortable playing a clean electric guitar. I think that's the seed of all of this for me. I learned and stuck mostly to the acoustic guitar for at least half a decade of playing, if not longer

Thanks for speaking to us today. I gather you're currently working on new music, as well as the channel relaunch?

“I'm finishing up a very busy album at the moment that is a collection of different experiments that failed along the way. I've mostly hated the process, [but] it's very much like, a healthy practice for me to finish this stuff.

“So that's going to consume me musically for the next little bit, but not too much longer. I'm almost done. I'm looking forward to the next step, which will be a lot more sparse and a lot more simple.”

Most people will know you as a demo maker, but what's your background as a guitarist?

“I'm still uncomfortable playing a clean electric guitar. I think that's the seed of all of this for me. I learned and stuck mostly to the acoustic guitar for at least half a decade of playing, if not longer. I couldn't tell you why I switched to electric, because I've never really liked rock music. There wasn't an artist that made me feel that the electric guitar was cool, or like something I wanted to do. I think I was just ready for some change, or to play louder [laughs].”

Playing loud to annoy your parents, or...?

“I took up the guitar later in life – it's quite an odd thing when I consider the alternate timeline. I think I was very close to not being a musician. I was only 18 when I started the guitar, and I did it as a course in high school, because I thought it would be easy – I was not musically inclined... Well, that's a lie.

“I was making beats, I was making hip-hop productions, but I had no interest in the guitar because it wasn't the music I listened to. So it was dumb luck. I didn't even like it [at first], but then my taste in music changed, and I started to like music that had guitars in it.

“Then having that bare minimum of awareness, and making friends with people that were making music with guitars meant just enough exposure [to the instrument].

“So I can probably attribute it to friends, because what I was doing was enjoying this acoustic, very mellow music, which was what the guitar was for me. Then I made some friends who were very into improvisation and basically jam-band sort of stuff, which I never got into, but I started playing electric guitar as a result, and I started to appreciate improvisation.”

You really came at the electric guitar from an oblique angle, from the sound of things.

“I sucked at it – I was always behind. Especially with the electric guitar being so much louder, I think I was just uncomfortable playing it clean – for good reason.

“I was always the worst musician in the room, so then I think playing an echo, like one of the old Boss delays, was really a great moment for me, because I wasn't able to play tight, but once those echoes were going, they're very precise and rhythmic, and I could follow them. That was the first moment where I was like, ‘Oh cool, I'm making good music with an electric guitar.’”

I think of the guitar like another sampling source among many, and it's just one that I happen to play better than the rest

Were you playing live during this period?

“I'm not going to say I had low musical self-esteem; I just had low expectations for myself, in terms of playing the guitar. I would sing back then, so I was playing shows and stuff like that, but the guitar was just there to fill up space and be a support element.

“I didn't expect it to ‘do’ anything, so that delay was a moment. It really was only when I started looping, and in a very experimental way, that I was like, 'Oh, I like these sounds.' I remember one loop in particular in a friend's basement where I realized this was music that I would listen to, and that I hadn't heard before.”

So you were playing acoustic shows and then privately making more experimental, loop-based music? There's probably a cohort of guitarists in the current generation who would really identify with that introverted creative process...

“Using the word introvert is [appropriate]. To me, playing live has never felt like an essential part of music, and music does often feel like a very private practice to me. Probably that's because it's how I started, arranging samples in my basement. That was my formative music experience.”

That approach to sound design sounds like it's really influenced how you see the electric guitar – as another texture that's part of a whole.

“Absolutely, yeah. Every day, or every week I have one day where I remember that I can just play guitar, that I could record a song that is just me playing this guitar. But as soon as I sit down to work on music, I don't. I think of it like another sampling source among many, and it's just one that I happen to play better than the rest.”

It sounds like that is almost the jumping off point for the style that ended up being in your demos. What was the initial motivation for doing the demos?

“I think I did it because of my musical preferences. At the time, ProGuitarShop was doing their thing, Mike Hermans was doing his thing, and it basically catered for rock-oriented guitarists. Which I would say is most guitarists, but I was often more interested in the most obscure feature that a pedal would have, and getting a zoom-in on that, without having a specific guess at what your intent was.

“Because, you know, Andy [from ProGuitarShop] in his videos is playing rock music, so there's this embedded assumption that you're probably going to do the same. [laughs] Which is a fine assumption, but I wasn't.”

I can remember digging on forums in the mid-2000s for information on pedals like the DigiTech Space Station, and only finding baffled players trying to play blues with it.

“I would always watch those videos and not have my questions answered, so I thought it would be interesting to make a [neutral] demo – and I failed, ultimately, because I don't think any music is neutral – but in the beginning, that was kind of the idea.

“That the music itself wouldn't get in the way and the point would be that pretty much any question you had about the pedal would be answered over the course of the demo.”

The first demo of yours that blew up was the Montreal Assembly Count to Five, which wasn't long after you started doing demos, right?

“That was the second one. The first one was the Reverberation Machine, by Death By Audio.”

Do you think the uniqueness of your demos was helped by choosing exotic or esoteric pedals for your first demos? As in, outside of the r/guitarpedals forum on Reddit, how many people back then even knew that the Count to Five existed?

“It's kind of cool to think about that. It wasn't that long ago, but it was definitely different.”

At the time, there were something like 20,000 members in that forum, and now there's 150,000, for starters.

“I think something has changed, and maybe this is the point of this article – I think it is. Something has changed, in that people are really, really attuned now to what's happening, and digging in the crates – in pedal form. At the time, it wasn't really that way.

“It really was the depths of forums was where you had to go to find experimental effects. So boutique stuff still existed, but there were tiers of it, you know?

“There was Z.Vex, and other companies that people were aware of, but then there were a lot of other companies doing work that most people weren't aware of. There weren't avenues to access that stuff.

“The Count to Five felt like a moment to me. It seemed like it was one of those weird times where everybody was like, ‘This is different’ and was like very, very excited. I think it was like, the first truly experimental time effect that had been made in a pedal format.

I remember checking the statistics on my Count to Five video and going, 'Oh s**t, this is happening'

“There were rack units that did similar things, and you can argue that the Space Station and others covered some aspects of it, but the Count to Five just embraced it wholeheartedly.

“It was the first of its kind, or at least the first that was really embraced and celebrated as a place you could go to get quirky sounds, and be just surprised by every single setting on a pedal. There's no way of getting a traditional effect. If you're getting this, you're looking for surprises, and I think that was a bit of a moment, as far as pedals go.”

Besides the pedals you chose, there was something about the audio and visuals that resonated with a lot of creative people. How did you come up with the aesthetic for your videos?

“That's a great question. [long, long pause]”

Because communicating without words is hard, but obviously something you did clearly resonated.

“[Pause] That was a really amazing time, I will say. The Reverberation Machine demo I was happy with, and some people watched it, I can't remember. The Count to Five one, I remember checking the statistics and going, ‘Oh shit, this is happening.’

“I think it just felt right... and that aesthetic and that energy were very in line with who I was at that time, which is almost 10 years ago now. The tone of voice and the objects and things like that, it wasn't a master plan.

“I wanted to focus on the pedal, so I knew that it was top-down. I wanted a nice piece of wood. It was really very functional – I wanted to clear out all the distractions. So there you have it, it's on this piece of wood now, and it's hard to talk about this without sounding like a weiner, but it's like painting [laughs]. When you're just doodling, why do you suddenly put a line here and a line there?

“To me, when you consider that frame like a white piece of paper, once I had the pedal down there on the piece of wood, I was like, 'Well, I need some other stuff now,' so I just grabbed what was around and arranged it in a way that felt pleasing to me.

“I definitely think you're always channeling some stuff, people brought up the fact that they look like I Spy books, which I definitely loved and read as a kid. The tone of voice and stuff, that just came naturally.”

It reminded me a bit of the old Aardman Morph animations. There's a playfulness and sense of humor to it.

“Totally. The practical part of my mind did genuinely want to explain these pedals really well, so all the other parts of my mind got to just play with all those other details, like the aesthetics.”

The other interesting thing is that guitar subculture and pedals subculture feel like they've diverged since then, and your videos feel like they belong in that discussion.

“I think it's appropriate. It makes a lot of sense that they're separate. In general, guitar culture is quite different I think, from pedal culture, and driven by quite different things musically, motivated by different musical goals.

“I think we're still at a point where pedals are naturally still attached to guitars, more people than not feel like they are extensions of the guitar rather than something that can be used with any instrument. But I fully expect that idea to dissolve at some point in the not-too-distant future.

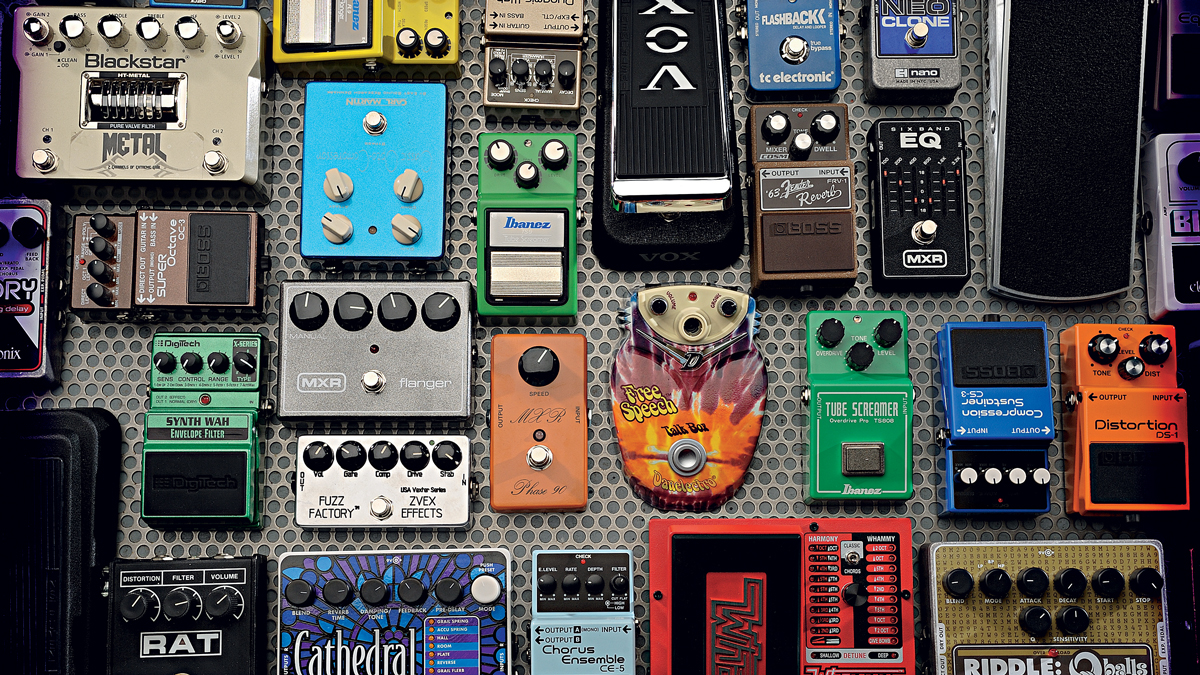

“The function of pedals has changed, too. They're now these collaborative devices that don't have a fixed function. For a good while they were guitar effects, and the purpose of them was to augment the guitar for specific moments.

People collect all kinds of things that genuinely do nothing. It's something about human beings that we do love to collect, and better it be guitar pedals than ornate spoons

“Like, ‘Hey, do we want to make things dreamy for a bit?’ Turn on a phaser. ‘Do we need a bit more aggression?’ Turn on a distortion. This very cut-and-dry, functional block. I think they're no longer limited to those functions, and there's a lot more value for pedals as... spice in the songwriting process, and as more like instruments in their own right.”

It feels like the other thing that's changed is there's also a significant part of the pedal scene that collect them as a hobby. As somebody who sees them as tools, that doesn't sit well with me. Am I looking at it from too narrow a perspective?

“I think it's natural to feel that way, but I think that it's perfectly valid for pedals to be hobby-level collector's items. To be toys. To be, like, stress-release valves. This is a totally valid use for a musical instrument, and I do think it connects with the idea that I've always felt about not feeling the need to play a show. Music can be a totally private practice.

“Pedals fall into that, and I think what you're latching onto is that pedal users, more than maybe other instruments, there's a subset that gravitate towards this ‘just for yourself’ kind of approach. But it's fine. I think it can be very healthy, and it's risky to assume why people aren't putting out music, you know? [laughs]

“Shopping for shopping's sake isn't the best behavior of all time, but people collect all kinds of things that genuinely do nothing. It's something about human beings that we do love to collect, and better it be guitar pedals than ornate spoons.”

Could it be argued that assembling a collection is itself a creative act?

“I think it's super-fascinating. It's a tangled web. Most of us agree that the planet is melting, and these are things that consume resources. If you zoom out far enough, it's hard to argue that it's not problematic on some level... I think it's a personal choice, but I'm not really a collector.

“Despite what I'm saying, I actually sell most of the pedals that come through for these demos, because I don't feel good if I'm not using them. [pause]

“I think it's important to remember that everyone's just fuckin' holding on, in whatever way that they can. This stuff makes you feel down, but for other people this might be the comfort blanket that they know is waiting for them when they get home. So they're not recording and releasing music, but these pedals make them feel safe, and comfortable, or just excited, and I think that's really valid.”

Given that your musical interest has always been in sound design and texture, your recent forays into modular make a lot of sense. I've often wondered if pedal users like the ones you describe would be happier with modular synths.

“Modular is the most fascinating corner of music technology by far. It's such a rat's nest. I'm trying to choose my words carefully, because we can only walk down one or two of the 50 paths I want to walk down right now. I think there's a very different mindset within modular.

“There's like, an agreement between all users and all producers that the point is to go further. Because modular is a hassle. You're doing all kinds of work that other instruments do for you, and the reason you do that is because you want freedom and choice.

If somebody creates something with sound with the intent of it making music, it could sound like absolutely anything... Intent is what separates a podcast from music

“Whereas even in pedals you see pushback from people, ‘Why does this pedal need 12 knobs?’ which to me is like, ‘Shut up. Because it has 12 knobs! Why do we need to talk about that?' If you don't want it, don't buy it.

“With modular, those conversations don't happen. Everyone's like, ‘Hell yeah, we're doing something new? Let's go.' So in that way I find it healthier experimentally, even in just the conversations around it. What that leads to is that almost every modular device has something to get excited about, often multiple somethings, and are pushing boundaries.”

Right. The experimental fringe of guitar and guitar pedals is just the mainstream view in modular.

“Modular is such a challenging way to make music, because it places the burden of being the inventor on you. Every person that's making modular music has to design their own instrument, and in many cases their own studio, and there's no handbook.

“Having the ability to design an instrument, but also replace parts when you feel like it, is so strange. I'm no closer to having a handle on it now than I was. I do just feel like it's not for everybody... but you learn so much.

“That's the thing: if you're in any way interested in an educational experience in music technology, then modular is 100 percent worth it for you. You learn all these things about your assumptions and biases.

That's the coolest thing about the guitar: it's this gateway into endless possibilities with sound. For you, where do you think sound ends, and music begins? Is all sound you work with inherently music?

“[Pause] I'm gonna go ahead and say yeah. Because I wouldn't know where to draw the line. Is a tape recording of two people having a conversation music? Okay, probably not, but at what point does it become music? If somebody creates something with sound with the intent of it making music, it could sound like absolutely anything.”

If you quantized the conversation to a grid, that'd probably qualify.

“Easily, yeah. But what if you just put it through a phaser? Even that? Yeah! Intent is what separates a podcast from music.”

If intent is the minimum line that divides sound from music, then it does make the art of sound even more fascinating.

“I think so. The reason there's no need for snobbery or gatekeeping is that making low-effort music doesn't mean that anybody's going to listen to it. And if you make low-effort music and people listen to it, that's awesome, because it's always hard to get people to listen to your music. And you can never twist anybody's arm, you know?”

So what is it you love about music?

“[Long exhale] So many things. As a musician, nothing comes close to the sense of satisfaction and surprise I get from making music. At this point at least, I've never gotten used to being able to make music that I like.

“Even just yesterday I made something, and I'm not saying it's spectacular, but on a personal level, I made something, and then I fist-pumped after I was done, because I was like, ‘Holy shit! Where did that come from?’ There's nothing else that I do that makes me feel that good.”

Alex Lynham is a gear obsessive who's been collecting and building modern and vintage equipment since he got his first Saturday job. Besides reviewing countless pedals for Total Guitar, he's written guides on how to build your first pedal, how to build a tube amp from a kit, and briefly went viral when he released a glitch delay pedal, the Atom Smasher.