Les Claypool: "I’ll go 20 years without changing my gear, and then I’ll say, 'This sucks - I’ve got to change everything!'"

Primus's slap-happy oddball on prog, gear and the challenges of making The Desaturating Seven

You can call Les Claypool many things, but you can’t call him idle. Between various iterations and re-launches of Primus, Les has fielded a wild variety of side projects, musical and otherwise.

These include freaky projects such as the Claypool Lennon Delirium (with Sean Lennon), Oysterhead (with Phish’s Trey Anastasio and the Police’s Stewart Copeland), Colonel Claypool’s Bucket Of Bernie Brains (with P-Funk’s Bernie Worrell), and mash-up outfits known as the Fearless Flying Frog Brigade, the Holy Mackerel, and Les Claypool’s Fancy Band.

He also helms a winery, Claypool Cellars, and recently launched a soda for queasy-stomached seafarers, SeaPop. He’s made a film and written a novella. He designs his own instruments, known as Pachyderm basses.

Amidst all of that activity, this year he and his Primus bandmates, drummer Tim “Herb” Alexander and guitarist Larry “Ler” LaLonde, returned to Claypool’s backyard studio for a unique project, The Desaturating Seven. It’s an ambitious concept album based on Count Ul de Rico’s beautiful and intense children’s book The Rainbow Goblins.

“When my kids were little, my wife would read to them every night before they went to bed,” Les remembers. “Every now and then I’d get up there and read to them, and they had this book, and I was like, What the hell is this?”

Featuring stunning oil-on-oak illustrations painted by the author himself, the dark story of goblins stealing colors from the land got Les hooked. “I found it very compelling. I thought it would make a great record, and now I’m finally getting around to it. It’s also pretty relevant to what’s going on today—the notion of those in power being gluttonous and using up all of the resources, and the meek banding together to thwart them.”

After a while, you start realizing you’re getting long in the tooth. You’ve got to start knocking these things off the list while you still can

It’s the first album of original Primus material since 2011’s Green Naugahyde, and the follow-up to 2014’s Primus & the Chocolate Factory With the Fungi Ensemble, an interpretation of the Willy Wonka soundtrack [both on ATO/Prawn Song]. And it’s great.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

At times bright and King Crimson-y, other times dark and creepy, Seven is a sharp turn toward thematic progressive rock. Tempos, meters, and dynamics shift throughout, with hard-hitting sections that give way to cavernous spaciness and back again.

Herb’s drumming is textural and painterly, Ler alternates between attacking and layering color, and Les is his characteristic galumphing, sliding, tapping self, only edgier than ever. His Pachyderm 4-string anchors most of the pieces, and he hauls out his old fretless Carl Thompson 6-string for upfront tap-and-slide sections that lead the rhythmic charge, also checking in on his NS Design electric upright. (What’s better than a tense, suspenseful arco theme to open a prog-rock concept album?)

The Desaturating Seven isn’t the typical career move for a 50-something band once considered part of the funk–metal movement—but this is Primus, a band so uncategorizable it once had its own genre category in the metadata of mp3 files.

“We never made hit records,” Les laughs as we sip SeaPops on the patio of his longtime Northern California home-and-studio hideaway, Rancho Relaxo.

“When we first started having brushes with selling records, it was such a shock. But when it happens, it gets in the back of your mind, and record people are getting in your head and you start thinking about that stuff, and it messes you up. Now, when we make records, it’s back to who-gives-a-shit. It’s about just making what we think is cool.”

Like the Willy Wonka record, Seven has been churning in Claypool’s mind for some 20 years. “After a while, you start realizing you’re getting long in the tooth. You’ve got to start knocking these things off the list while you still can.”

Your main, fretted bass tone is nicely consistent throughout the new record. Was that a conscious effort to tie everything together?

That kind of just happened. It’s funny, because I was chasing my tone throughout the recording process, so it’s good to hear that it came out sounding consistent. When I set up for a recording, usually I get excited and I start plugging stuff in, and there’s a buzz here or something is clipping there, and I forget about it—and the next thing you know, I’ve laid down what’s supposed to be a scratch track, but then I love it. I want to keep it, but it’s cracking and buzzing, and I can’t figure out how to get it back.

I’m not a gear guy; I’ll go 15 or 20 years without changing my stuff, and then I’ll say “This sucks—I’ve got to change everything.” In fact, I just did that, right after I made this record: I got a Fractal Audio AX8 Amp Modeler, so that’s what I’m using live now. I think I finally got a tone that I’ve been searching 30 years for [laughs], but that might change next year. I’ll say, Oh shit, I should be playing a Rickenbacker with flatwounds. Who knows—you get bored and you try other things.

Your fretless Carl Thompson 6-string is a common thread throughout your career.

Carl Thompson basses are amazing, but each one is unique, and you tend to tailor your playing to the instrument. Also, I kind of wanted to retire my Carl basses because I didn’t want to bring them on the road anymore. I was starting to worry about them.

I wanted something that was my vision—something that I designed. So my buddy Dan Maloney is making me these Pachyderm basses. I’ve known Dan since high school. He’s a little older, and he drove us to Rush’s Hemispheres show at [San Francisco’s] Cow Palace. I drank three Löwenbräus and threw up in the parking lot.

So the Pachyderm is the only fretted bass you’re using?

That’s the one. I started by designing it on paper, and then I cut the shape in plywood. It’s fun experimenting with all the different woods. I’m a big fan of maple, but if you do all-maple, the tone is really intense. The Pachyderm basses are light as hell, and they balance very well. I’m getting older, and my back is messed up. Actually, I just lost 20 pounds—I stopped eating bread and sugar, so I’m feeling a lot better.

What was the first thing you did to get into writing the album?

I wrote “The Storm”—the lyrics, the whole arrangement—and I recorded it. I listened to it and thought, Is this a little too ’70s art-rock? It’s very hard to write about goblins and rainbows without sounding like you’re in Tenacious D.

Timing-wise, it was time for a Primus project, so I played the song over the phone for Ler. I was like, Is this too Jethro Tull, or Utopia’s Ra? You know, [sings] Hi…roshima, Na…gasaki! But he absolutely loved it; he flipped out. Then I played it for our manager, and by that point Ler was already clicking away on ideas. So, I just started writing the rest of it, and away we went.

And how do you write something like that?

This project is very much just me. I basically sat in that room over there and went through the story, and I broke it up into different sections, like a play. I think “The Seven” might have been the second song I wrote, and I knew the record would have an intro and an outro, like an essay. Primus was out on the road for seven weeks [in the summer], and we played “The Seven.” We started playing that one pretty much right away.

Part of that song is in seven, but you have a way of making songs sound like odd time signatures even when they’re in 4/4.

I usually have no idea what the hell time signature I’m in. I know four. When I did that project with Adrian Belew and Danny Carey [Belew’s Side One and Side Three, 2005–6, Sanctuary], they were rattling off all these time signatures, and I was just trying to find my anchor. I’m not a counter; I’m not good at that. I just feel it. When I have to count, I’m in trouble.

Did you find it more difficult or liberating to work under the constraints of a concept album?

Every time I’ve tried to do some kind of concept album, I stepped away from it and said fuck that, because it is constraining. All of a sudden you’re putting up parameters, whereas most of my stuff goes all over the place; I stumble across some weird thing and say, Oh, there’s a song. You can’t necessarily do that when you’re trying to tell a story.

Do you mean lyrically, or musically, as well?

At first I was a little concerned about the music, because it was all, [sings] Dun de dun, de dee de dee—very Dungeons-and-Dragonsy. But Ler’s and Herb’s playing add a lot of contrast, which helps.

Herb seems like the perfect drummer for the project, because he’s so atmospheric.

He’s also a very melodic player, and he’s good at playing in odd time signatures without it sounding swimmy or washy. He knows how to play in odd times but keep a strong anchor; there’s still a sense of a pulse.

When Primus did Green Naugahyde with Jayski [Jay Lane], it was more of a groove record, because Jayski is more of a groove drummer. We were in a groove frame of mind—whereas with this album, we said, “We’re going to make an old ’70s art-prog-rock record.” We were going back to those roots, which we all had very common ground on.

When we first auditioned Herb many years ago, what did we do? We played Rush tunes. Whereas when we sat down with Jayski, we were playing Isley Brothers tunes or Prince or whatever. So this record was definitely in Herb’s wheelhouse, that Bill Bruford/Neil Peart feel.

Do you find yourself changing your approach when you go from one drummer to another, or does it just happen?

I imagine I think about it, but not terribly. It’s like having a conversation: You don’t necessarily think about it when you’re talking to someone different, depending on how different their perspectives are.

I always go back to that conversation metaphor with music. You get to a point with your instrument where it’s like talking. Yes, it’s wonderful to improve your vocabulary so that you can complete your [pause] sentences [laughs]. But your playing just naturally changes when playing with different people, the way a conversation would change if I was talking to you versus my dad.

I loved playing with Paulo Baldi on that Delirium stuff; he has this feel and this way to his drumming, but it’s very different from Herb or Jayski or Stewart [Copeland] or any of these guys I play with.

What does it require to learn an album of complex material for an upcoming tour?

I just have to go through and figure out what I did. It shouldn’t be that hard. It’s more about trying to lay it all out so that it trunk-and-tails together, and also getting all of my loops happening, because there are a lot of loops and sound effects to get together. As for rehearsing the show with the band, I’m hoping we can pull it off in four or five days.

Are you still using your original Boomerang Phrase Sampler?

Yeah, I like the old one. When I did the Oyster-head project, Trey [Anastasio] had one, and I was like, Oh, that’s cool—and I’ve been using it ever since. I can’t find anything to replace it. The original version has a lo-fi quality that’s cool. And, I’m used to it; it’s easy to deal with. The newer version confuses me.

You mixed and engineered the new record yourself?

I did. I’d have my tech come in and kind of clean up and straighten up cords and whatnot, but engineering-wise, there was nobody else. I bought this old API console, which is phenomenal, but I recorded in Pro Tools, so I only use the board for color. I have a two-inch 16-track tape machine, but it’s too much work getting the tape and keeping the machine aligned and everything.

I do use a lot of outboard gear, like Mercury compressors, which are unbelievable replicas of old Fairchild compressors. I use them on vocals and bass. My pedals usually go right under the console, and Herb sets up in my son’s man cave, and we run a snake.

With all of your production experience, do you go back and listen to old recordings and say, 'Oh my God'?

For sure. It’s funny, when you’re recording something, you’re like, “This is the greatest tone I’ve ever gotten in my life.” And then you listen three or four or ten years later, and you’re like, What the hell was I thinking? But then you give it another few years, and you’re like, Wow, that actually sounds amazing.

The label is re-releasing a bunch of the Primus records for vinyl box sets, and it’s funny to hear the contrast in the records. We were always experimenting because we’re kind of dumb. Like, for the Brown Album [1997, Interscope], we used the tape machine and we hit it way too hard, and the tones are all farty—but it has this certain quality.

The record industry is a whole new ballgame now; records have become almost promotional items so you can sell concert tickets and T-shirts. We’re lucky because people have always wanted to come see us waggle our fingers and stuff. Our record sales are still a fraction of what they used to be, but we put everything on vinyl now, because that’s one way to get people to buy something physical.

Do you find it harder to get fresh ideas as you get older?

I actually find in some ways it’s easier. You go through periods when you don’t feel like doing anything, and you just feel like going to catch a fish or whatever. If I did only Primus all the time, I would dry up. But I get to do all of these other things, which is phenomenal. Doing the project with Sean opened huge doors for me. I got keyboard credits on that record—who would have ever thought that? Also, I learned to approach vocals differently, because Sean knows what he’s doing vocally.

So playing with other people is the key to staying musically fresh?

It’s the key for me. I remember, toward the end of the 1990s with Primus, feeling that the well had dried up, on all levels—personally, creatively, enthusiastically. Getting away from the band and doing other things was the smartest thing I did for my creativity.

I learned how to become confident in my voice, I got more confident with my writing, and more confident about playing with anybody. It’s a smart business move to nurture your brand and stick to it and build your brand, but for me, it wouldn’t have been a smart move creatively. When Ler and Herb and I get together, there are certain things that come naturally—but if we did nothing else, we’d be spinning in circles.

Tell us about your adventures in the wine business.

It’s just about starting to break even. This region is the Mecca of California pinot, and I’ve been spending my children’s inheritance getting the business going, but my wife loves it, and it’s been a great transition thing for her.

She had always said that once the kids move out, she’s coming on the road with me, and she did on this most recent tour—I bought an old tour bus, and she was out on the road with me doing wine events. We had a great time. This is the first tour I’ve ever done where I wasn’t excited to come home.

Our winemaker is one of the most sought-after pinot makers in the area, and the only reason I got him is he’s a bass player. He was a fan, and we've become very good friends. We make great juice, but there’s an old saying: If you want to make a small fortune in the wine business, start with a large fortune.

Where did you get the idea for the SeaPop soda?

I did that for myself. I love being on the ocean, but I hate motion sickness, and there was nothing that would help me. So I looked into natural remedies that sailors have been using for centuries, and came up with this. It also helped some friends of mine who were going through chemo—they loved it. It helps with acid reflux, and it has anti-inflammatory properties, too.

What’s in your future?

I’m going to New York to start writing the next Delirium record with Sean. So hopefully he’ll come out here by the end of the year, and we’ll record it.

Are there any new directions that you want your bass playing to go in?

Nah, it’s back to the conversation thing. You just want to hone your conversational skills. And, different things turn your crank at different times. On this last Primus tour, we were playing more aggressively and heavier, so that’s exciting. Also, this new record is very proggy, and it’s been a long time since we went heavily down that path. A big part of turning over new stones is flipping over old ones.

Goblin gear

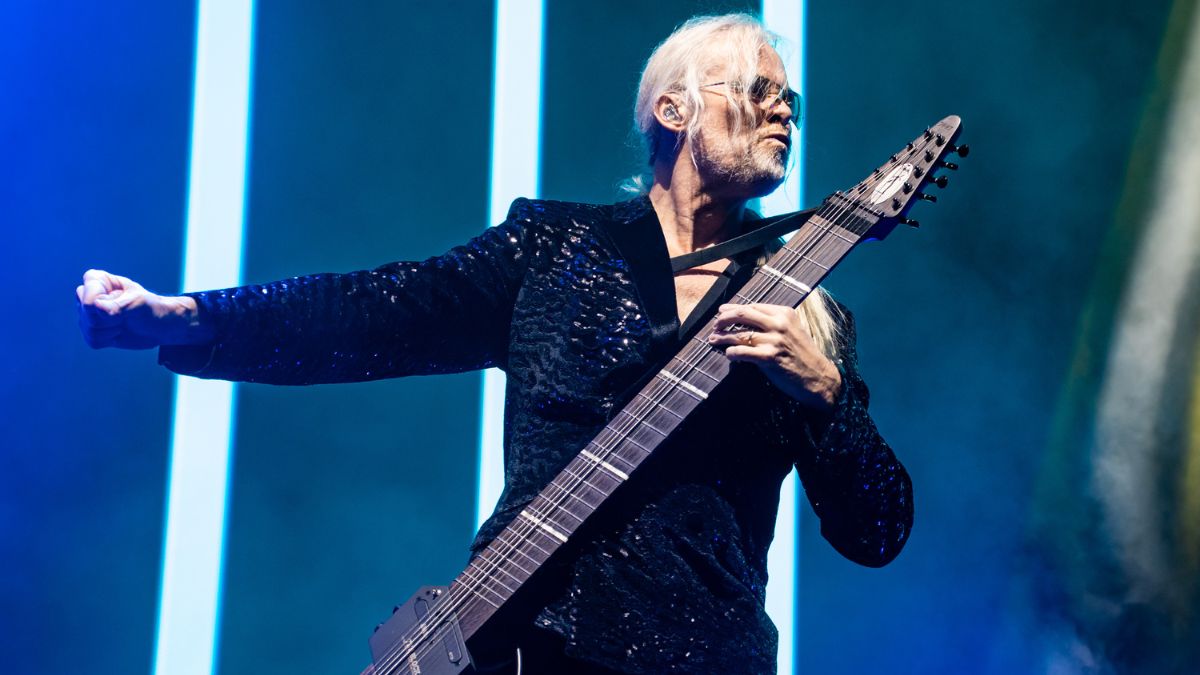

Long known for his Carl Thompson basses, in recent years Les Claypool has manned Pachyderm basses for fretted 4-string duties. Designed by Les and built by his old friend Dan Maloney, Claypool’s latest Pachyderm (strung with light-gauge Dunlops) has the EMG pickup moved a bit closer to the fingerboard compared to previous iterations.

The bass is incredibly lightweight and zingy, with perfect balance. It has one knob for volume (“I like simple,” says Les), and a switch for the fingerboard side markers. Not only are the dots LED-illuminated, they’re also slightly raised—giving tactile cues that help Les navigate the neck without having to look.

Fewer than a dozen Pachyderms have been built, with several being sold to collectors for charity. For more information, go to pachydermbasses.com. He still brings his fretless Carl Thompson 6-string and NS Design electric upright on the road.

According to tech Ryan Becker, for live shows these days, Claypool’s basses feed a Shure UR4D wireless system; after a switcher, his signal encounters a Line 6 DM4 Distortion Modeler, Line 6 DL4 Delay Modeler, and first-generation Boomerang Phrase Sampler. These go in the effect loop of a Fractal Audio Systems AX8 Amp Modeler + Multi FX, which sends a signal to the house.

To record The Desaturating Seven, Claypool’s signal chain was even simpler: just his old MXR 10-band graphic EQ and MXR M80 Bass D.I.+, which also provided distortion.

Karl Coryat was Deputy Editor of Bass Player magazine in the 1990s. In the 2000s, he wrote two music books: Guerrilla Home Recording and The Frustrated Songwriter’s Handbook, the latter with Nicholas Dobson. In 1996, he was a two-day champion on the television game show Jeopardy!. He works as a comedian and musician under the pseudonyms Edward (or Eddie) Current.