Paul Chambers: the double bass great's best (and worst) albums

Highlights from the jazz legend's catalog ranked and rated – Kind of Blue is number one, but what else makes the cut?

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The life of the late Paul Chambers was short, but his influence on double bass in the world of jazz is huge. Chambers was born in 1935, and his first musical steps included jamming on the baritone horn and the tuba.

By 1949, though, he’d settled for the bass, and three years later was learning his craft with experts from the Detroit Symphony Orchestra. That wider musical appreciation was key to his understanding of the art of arrangement and instrumentation, and secured him places on tour with Bennie Green, Kai Winding, Wynton Kelly, and the Miles Davis Quintet.

Chambers became a sought-after session player, and worked with numerous household names including Chet Baker, Thelonious Monk, Wes Montgomery, and John Coltrane.

Noted for his perfect timing, gorgeous intonation, and unparalleled skill with improvisation, Chambers showed generations to come the vast possibilities of the instrument.

However, there was a dark cloud over the genius: Sadly, Chambers was beset by addictions to heroin and alcohol, and succumbed to tuberculosis on January 4, 1969 at the cruelly young age of 33.

Must-have album – Kind of Blue (Miles Davis, 1959)

This is the biggest-selling jazz record ever, and for many, the best album of all time. Famously, the material was entirely unrehearsed, aside from scant song sheets; each member of the sextet was at the top of his game, and was encouraged to explore the complex modal improvisation required.

Paul Chambers’ ability to shift quickly in tone and approach allows Bill Evans’ piano to encircle him, and such is the bassist’s mastery of his instrument that he introduces intermediacy between the notes.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

There’s innovation everywhere, even on the relatively straightforward 12-bar Freddie Freeloader, where Chambers’ main focus is on keeping the whole ensemble moving forward.

Perhaps the most iconic moment for lovers of the low-end is the opening of So What, with Chambers and Evans duetting around the seventh, ninth and fifth before that familiar syncopated high-reaching bass-line calls the band to action.

The walking line then gives Davis the center stage, as it later does to each other soloist in turn. With the innovative chord changes of modality established, this announced a new kind of jazz. This album is unparalleled.

Worthy contender: Art Pepper (Art Pepper Meets The Rhythm Section 1957)

The great Art Pepper was another troubled soul in a landscape of profoundly afflicted musicians. In his autobiography, Straight Life (1979), he wrote that he had not played his bashed-up alto sax for six months before recording this set, on January 19, 1957.

In fact, he didn’t know about the session at all until the actual day, and turned up loaded to the eyeballs on a dose of smack.

The Rhythm Section were Chambers, Red Garland, and Philly Jones, the trio that also formed Miles Davis’ contemporary Quintet, and though they’d never met Pepper, out of the chaos came something that was ultimately, against all reasonable expectations, much greater than the sum of its parts.

The sheer pace of the scales Chambers plays – without dropping a note – is truly incredible

Chambers stepped in with a co-write alongside the saxophonist in Waltz Me Blues, which features a smooth chromatic bass-line, a double-time solo way up the neck and a lovely glissando feature. It’s upbeat and zippy in feel, in complete contrast to the nitro-injected craziness of Straight Life.

The sheer pace of the scales Chambers plays – without dropping a note – is truly incredible. In delivering this performance, he represents the West Coast bebop sound at its very finest, and even changes the texture with a lovely bowed section, too.

Cool grooves: Giant Steps (John Coltrane, 1960)

This appropriately-named album was recorded only weeks after the Kind of Blue sessions wrapped up, with the band still absolutely drilled and tight.

The rhythm is still very hard bop-influenced throughout, giving the cerebral bandleader Coltrane the basis to explore his intense harmonic development and his penchant for extremely fast soloing.

The title track has Chambers absolutely sizzling, as he continues to do throughout the LP. His solos on Cousin Mary and Syeeda’s Song Flute are among his very best, making it clear that Giant Steps was intended as a showcase not just for John Coltrane, but for the very best jazz players of the era.

Giant Steps became and remains a benchmark in recorded music. It’s commonly cited today as the perfect nexus of intellect and unbridled musical skill

Chambers even gets a track named after him – the speedy workout of Mr. P.C. – on which he makes use of the entire range of the bass neck without fear or favor.

It’s truly frenetic stuff, and when Coltrane finally shuts up for a bit, space opens up for a fantastic interplay between Chambers, pianist Wynton Kelly, and drummer Art Taylor that is a fine conversation indeed, with plenty of room for these immense talents to play around in.

It’s wild stuff, baby. Giant Steps became and remains a benchmark in recorded music. It’s commonly cited today as the perfect nexus of intellect and unbridled musical skill.

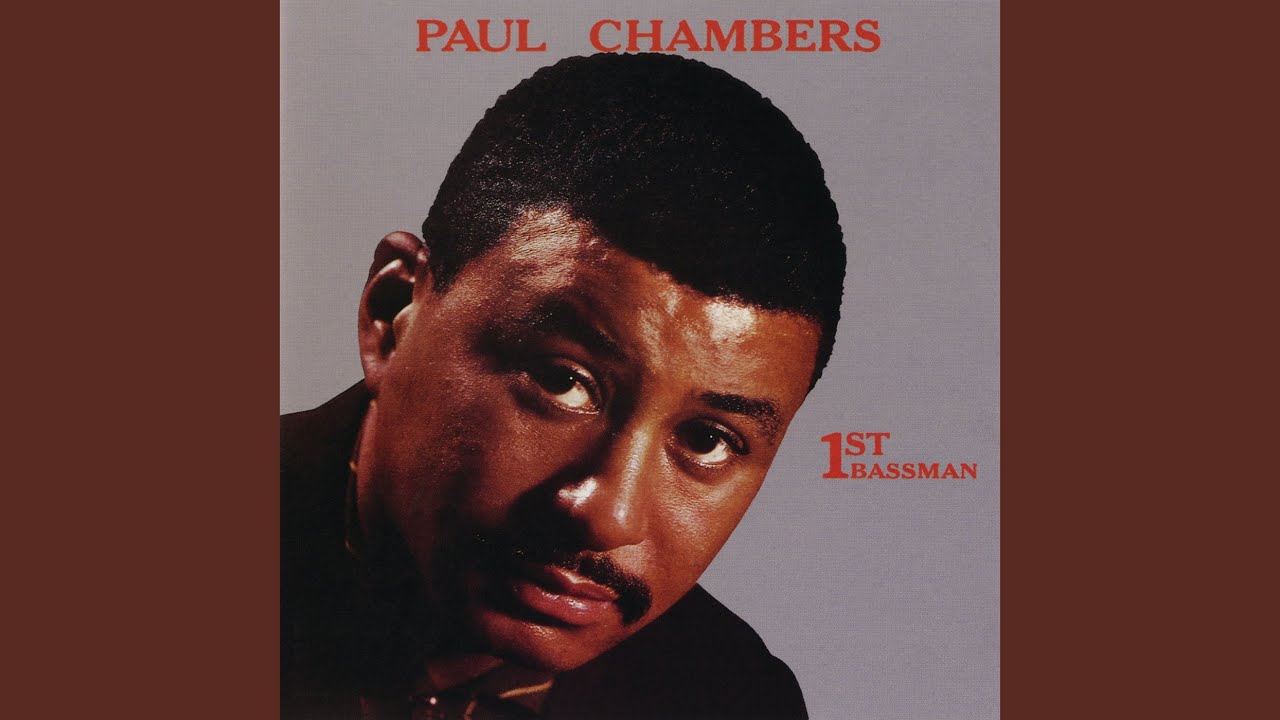

Wild card: 1st Bassman (Paul Chambers, 1960)

A bassist as bandleader is entirely allowed to do what he or she likes, and Chambers was quick to put bass front and center on yet another LP recorded in this verdant period of his career.

All the tracks were written by saxophonist/flautist Yusef Lateef, with Chambers strutting his stuff as the lead melodic feature. A tremendous example of this can be heard on the mid-paced Mopp Shoe Blues, a 12-bar workout full of syncopation, fifths, sevenths and turnaround licks from the unstoppable bassist.

At the same time, however, the arco work on the plaintive Blessed is mournful and largo, with Chambers making full use of the resonance of the double bass; sonically, there’s a touch of harshness as catgut meets bow, only adding to the atmospheric mood.

More than anything, it is the sound of a stringed instrument playing what could happily be a woodwind line in any other context, which is entirely appropriate given Mr. P.C.’s musical history.

Between the bowed passages, Chambers locks down pizzicato roots, octaves, and turns as the other instruments take turns in modulating solos. The bassist then takes the opportunity to perform an arco solo in his own right, and correctly so: He’s the boss, after all. This album is perhaps the best clue we have as to his mindset as bandleader.

Avoid at all costs: Last Trio Sessions (Wynton Kelly, 1988)

These sessions were recorded in 1968, 20 years before their eventual release, and have not aged well, despite being created in a golden age for jazz.

Sadly, the inclusion of covers of popular hits is the album’s undoing, with Say A Little Prayer For Me reduced to muzak, despite Wynton Kelly’s speedy arpeggios. It’s the sound of a lounge band at best, and a huge waste of the talents of the trio, which was made up by Jimmy Cobb on drums.

The strange choice of the Doors’ Light My Fire doubles down on the cheesiness levels, predating the lounge-music trend of the '90s by a full three decades. Chambers himself seems to be going through the motions here, although there are some sweet glissandos to be heard.

Slightly more palatable is the reworking of Yesterday, which has some interesting chord work in the intro, at least.

It’s all a bit over-earnest, under-thought and dashed-off. The quality of the players involved demanded more than this, surely?

In parallel, the Beatles released their self-titled White Album in 1968, on the back of Sgt. Pepper, which makes Last Trio Session sound absolutely outdated, especially as at the start of the decade Chambers et al had been so exciting in moving music forward. Let this be a lesson to us all...

Bass Player is the world’s most comprehensive, trusted and insightful bass publication for passionate bassists and active musicians of all ages. Whatever your ability, BP has the interviews, reviews and lessons that will make you a better bass player. We go behind the scenes with bass manufacturers, ask a stellar crew of bass players for their advice, and bring you insights into pretty much every style of bass playing that exists, from reggae to jazz to metal and beyond. The gear we review ranges from the affordable to the upmarket and we maximise the opportunity to evolve our playing with the best teachers on the planet.