Paul Thorn: “Half the songs on this album were recorded on a Gibson Hummingbird with three-year-old strings!”

The Americana singer-songwriter talks cutting out drinking, how a Mississippi-shaped electric became his main guitar, and paying tribute to late family members on his new LP, Never Too Late to Call

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Paul Thorn never considered himself a country music artist. Still, he has reasoned, “I live in the country and I play music, so maybe I am.” That might hold true when reviewing the list of artists who have recorded his songs, but Thorn’s fanbase reaches across genres, repeatedly landing him on the Billboard Top 100 and Americana charts.

Born in Kenosha, Wisconsin, Thorn grew up in Tupelo, Mississippi, which he still calls home. His backstory is as unique and multi-dimensional as his music. His father was a Church of God of Prophecy evangelist… and his uncle Merle was a hustler and pimp.

By age three, Thorn was playing tambourine at revivals and singing in church. As an adult, he honed his craft playing nights in a Tupelo pizza restaurant. By day, he spent 12 years working in a furniture factory, skydiving, and boxing professionally on weekends for three years, including a televised fight against world champion Roberto Durán.

Through it all, music was his lifeblood. Signed by Miles Copeland, Thorn made his debut opening for Sting at the Nashville Amphitheater. His first album, 1997’s Hammer & Nail, introduced the world to his often angst-ridden, first-person confessionals, third-person narratives, and dry wit, all set to musical backdrops filled with an amalgam of influences that never strayed too far from his gospel roots.

All that is Paul Thorn is reflected on his latest release, Never Too Late To Call. Anchoring the project is the title track, a poignant tribute to his sister Deborah, whom he lost in 2018. She was his “person,” the late-night call he would make from the road, after the show was over and he needed to talk.

Recorded at Sam Phillips Studio in Memphis with Grammy-winning producer/engineer Matt Ross-Spang, the 11 new tracks are classic storytelling Thorn: sometimes heartbreaking, other times exuberant, at all times universal.

When you look at your career, who was the young man who recorded Hammer & Nail, and who is he now?

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“That kid had a lot to learn. He’s had a lot of good things happen and a few bad things too. I got signed to a major record label, but like most deals, nothing came of it much.

“What was good, though, is that when my deal with A&M was done, my songwriting partner and manager, Billy Maddox, and I decided to start our own record company, and as a joke we called it Perpetual Obscurity Records. I may be wrong, but I think we might be the first true independent Americana label, because we pressed our own CDs.

“When I had my A&M deal, I got to go on tour opening for Sting, Mark Knopfler, Jeff Beck, and Toby Keith. People didn’t come to see me, but some of them liked me, and so when we got our independent label going, we went back to those same towns, and some of those same people came back to see us.

“Slowly, I started building my audience. Today, at the age of 57, I’m not a household name, but I have a very loyal following that has supported me all this time and it’s been great. I’m very happy with what’s been accomplished so far.”

I was sitting on the couch with an acoustic guitar, and as it was coming together, I would hear my wife in the kitchen singing harmony with me and it sounded amazing

Is it accurate to say that Never Too Late To Call is in some ways a family album? Your wife joins you on Breaking Up for Good Again, your daughter Kitty joins you on Sapphire Dream, and your sister Deborah is with you in spirit on the title song.

“I’ve never called it a family album, but I’m cool with that. I like it. I think that’s a good way to describe it. This might sound corny, but I believe in God, and I believe that God gives you life. But life is what gives you songs, and things that happened in my family gave me these songs.

“My wife also grew up singing in church, but she’s not a professional singer. But when I wrote Breaking Up for Good Again, which is about two people who love each other, but at the same time have bumps in the road and sometimes even need time apart, I was sitting on the couch with an acoustic guitar, and as it was coming together, I would hear her in the kitchen singing harmony with me and it sounded amazing.

“I said, ‘I want you to sing this with me on the record.’ After 22 years of marriage we’ve lived that song, and I think anyone who has been in any kind of relationship can relate.

“I wrote It’s Never Too Late to Call after Deborah died of cancer. Every night after shows, I would be wired and couldn’t sleep, but I could always call her because she would be awake. More than once I would apologize for calling so late and she’d say, ‘Don’t worry; it’s never too late to call.’ And that stuck. When she passed, I wrote the song in honor of her memory.”

Is songwriting visual for you? The pictures you create with words – the claw-foot tub and pickled pig feet in You Mess Around & Get a Buzz, the Country Crock bowl in Sapalo, and of course the 800 Pound Jesus – we can see those things when we listen to your music.

“I’m a visual artist as well as a musician, so yeah, it’s definitely in my head. I just have to figure out how to make lyrics out of it. One of my favorite songwriters is Hank Williams. His name gets thrown out there a lot, but there’s a reason for it. It’s his economy of words.

“‘As I sit here alone in my cabin, I can see your mansion on the hill’ – that’s a simple little phrase, but it says so much. It’s powerful. I would never claim to be close to somebody like him, but the Kris Kristoffersons and John Prines of the world, that’s what you shoot for.”

You’ve called your Gibson Hummingbird your favorite guitar. How much of the album did you record with it, and what else are you using in the studio and on the road?

“The Hummingbird is in my living room. I don’t take it on the road anymore because I don’t want it to get damaged. I wrote all these songs on that guitar, which has three-year-old strings, and I sent the iPhone demos to Matt, who is a fantastic producer.

“He liked the way they sounded, so half the album was cut in the studio with that guitar and those strings. We wanted it to sound like the demos, and we were able to capture that.

“Matt has an old Giannini classical gut-string guitar in the studio that sounds amazing. It’s got a gigantic neck and it’s hard to play, but that’s the one I used on the other parts of the record.

Over the past years I’ve really gotten into the simplistic, less-is-more approach of artists like JJ Cale. My dream was to do a record like that, and good or bad, that’s what I accomplished this time. It’s not perfect, but it’s real

“Another thing about this album is that it’s the first one I played guitar on, and the first time that every song is built around my acoustic guitar, with the band playing around that.

“The whole thing is very understated. Over the past years I’ve really gotten into the simplistic, less-is-more approach of artists like JJ Cale. My dream was to do a record like that, and good or bad, that’s what I accomplished this time. It’s not perfect, but it’s real.

“Since then, I purchased a new gut-string guitar, a 2000 Taylor hybrid with a thinner neck than the Giannini. I also have two Composite acoustics guitars made out of carbon fiber. One is in standard tuning and the other is tuned down a half-step. They’re fantastic for live performances because they never go out of tune. I’ve got one other regular acoustic guitar that was made as a present for me by a luthier. I use that one for songs that need something that sounds like a 12-string.

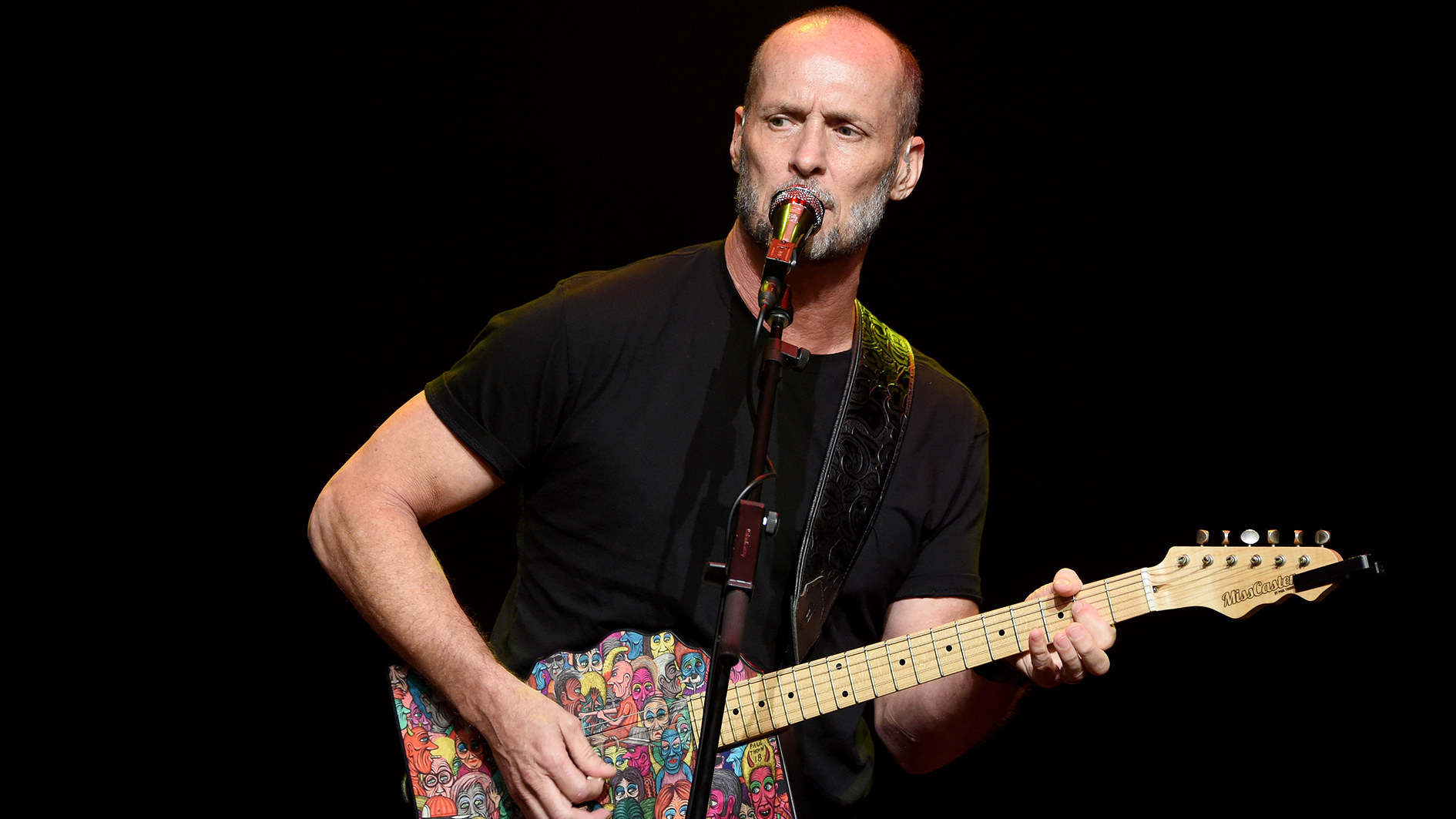

“I was playing a 1983 Telecaster, which is a great guitar, but now I play the MissCaster. I’m kind embarrassed to say that in 2018, the state of Mississippi declared March 27 Paul Thorn Day. I got to go to the Capitol building, and they presented me with a guitar that was shaped like Mississippi.

“I thought it was something cool that I could hang on my wall, but it was built by a really good luthier, and when I played it, I liked it so much that it became my electric guitar that I play every night. It was a plain piece of wood at first, so I painted a picture of my fans in all different colors, standing together in front of the stage, and that became the face of the guitar. It’s a high-end guitar and I’m proud of it. We made 25 of them, numbered and signed, and some are still available.”

It’s been seven years since you released a collection of new songs [Too Blessed To Be Stressed, 2014]. Obviously, this album was delayed because of the pandemic, but overall, why so long between albums?

“To be honest, it’s because I had turned into a heavy drinker. It slowly crept up on me. I always felt this immense pressure to put on the best show, and I got tricked by the devil, you might say: ‘If I take a couple of shots of tequila, I’ll be on fire. I’ll own the room.’

“Then it became, ‘If I take three shots, I’ll be even better.’ It escalated to drinking after the show and it just snowballed, and that vicious cycle takes away everything. You spend the night drunk and the day recovering, and when you’re recovering, you ain’t got the strength to do anything.

“As much as I loved recording with the Blind Boys of Alabama [Don’t Let The Devil Ride, 2018] and that tour, a lot of it was Billy Maddox, because he knew I was floundering and didn’t have any songs worth a damn to make an album. It was something to buy time because I wasn’t bringing anything to table.”

The one takeaway I’ve learned that helped me stay relevant is to just be myself. I know that sounds very simple, but it is true

In one of your interviews, you mentioned that the drinking got worse during the pandemic. Did grief play a part in that?

“Oh yeah. My sister died, and our little dog Oscar, who weighed six pounds, we took him outside to do his business in the yard, and out of nowhere a hawk flew down, grabbed him, and he was gone. So, you know, ‘My sister died, my dog is gone, let’s drink.’”

What made you stop?

“The bottom for me was when my youngest daughter, who is 17, said, ‘When Dad’s drinking, it makes me feel alone.’ When I heard about that, it kicked me right in the gut. It was a wakeup call. I stepped back and looked at myself. My face was swollen. I wasn’t writing.

“The good news is I quit drinking [in February 2021]. That might not sound like a long time, but when you’ve been drinking every single day to excess, it is a long time, and I am determined not to go back down that road.

“My story’s not unique. It’s common. But nothing’s going to work unless you really want to quit. That’s the bait. If you don’t have that, nothing works. Everybody’s bottom is different, but for me, it was when my daughter made that comment. That was all I needed to know.”

Over the course of 25 years, what have you learned that stays with you to this day?

“The one takeaway I’ve learned that helped me stay relevant is to just be myself. I know that sounds very simple, but it is true. I can go out there, be me, and capture an audience, and that’s something I’m really thankful for. It has propelled me to many things I never dreamed I’d get to do, and here I am, still doing it.”

- Never Too Late to Call is out now via Perpetual Obscurity Records.

Alison Richter is a seasoned journalist who interviews musicians, producers, engineers, and other industry professionals, and covers mental health issues for GuitarWorld.com. Writing credits include a wide range of publications, including GuitarWorld.com, MusicRadar.com, Bass Player, TNAG Connoisseur, Reverb, Music Industry News, Acoustic, Drummer, Guitar.com, Gearphoria, She Shreds, Guitar Girl, and Collectible Guitar.