Randy Jackson on his return to Journey, what makes a great bassist, and playing football with James Jamerson and Jaco Pastorius

Journey are back with a new album made with the returning Randy Jackson, whose story goes beyond bass. A&R, TV star, producer, entrepreneur... And to 40 million TV viewers, he’s the man who sat next to Simon Cowell on American Idol

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

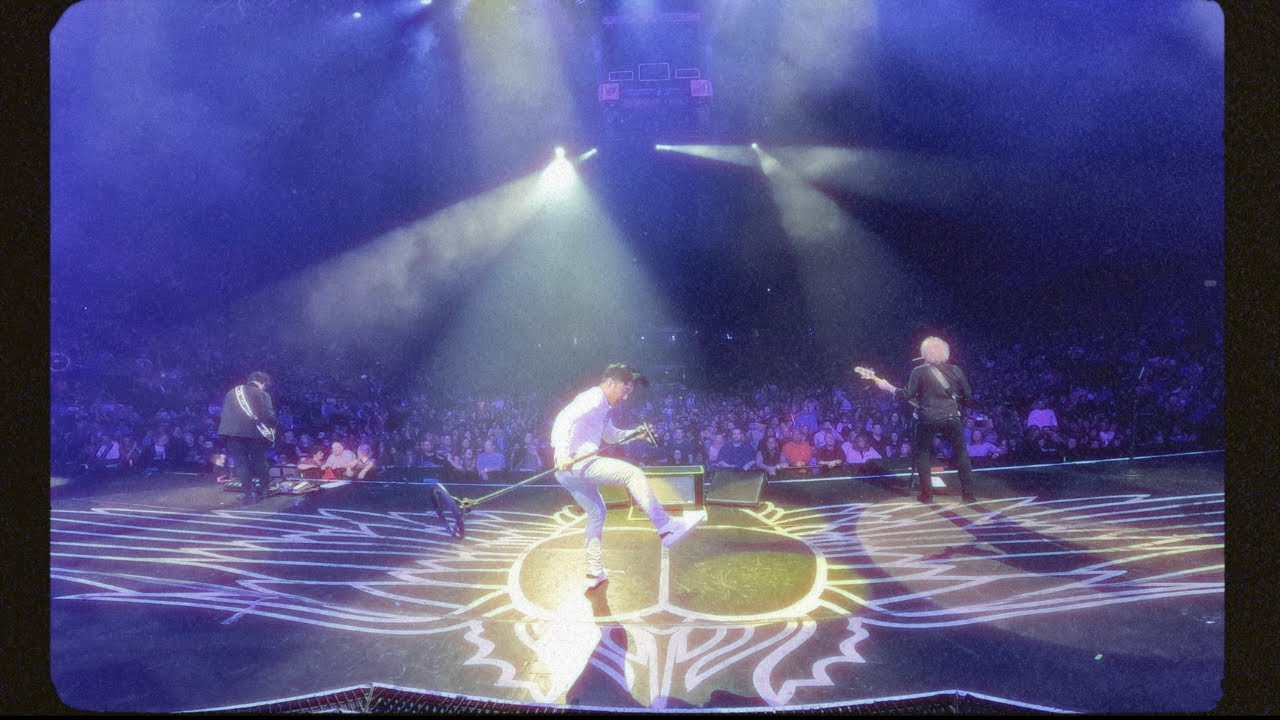

Randy Jackson, born in Baton Rouge, Louisiana in 1956, doesn’t have the usual bass-player biography. A fusion bassist from his twenties, having got his start with the French jazz violinist Jean-Luc Ponty, he found fame with the AOR giants Journey in 1986.

This kickstarted a long and prolific session career, whether playing pop hits with artists such as Whitney Houston or complex jazz with Billy Cobham, and he soon expanded his role to production, artist management, and then A&R, where he was a stalwart for many years at Columbia and MCA.

That’s a successful music-industry career by anyone’s standards, but Jackson’s appearances as a judge and artist mentor on American Idol on Fox from 2002 until 2014 made him nothing less than a household name.

Now that TV talent shows of this nature have receded from view a little, it’s easy to forget just how massive they were a decade ago: At its peak, say from 2004 to 2010, American Idol was ranked at the top of the annual US television ratings.

It created dozens of new musical stars, the best-known among them being Kelly Clarkson, Carrie Underwood, and Queen’s Adam Lambert, mentored by Jackson and his fellow judges Simon Cowell, Paula Abdul, Keith Urban, Jennifer Lopez, and others.

Many a musician despises the American Idol format, though – and to his credit, when Jackson talks to us today about Journey’s new album Freedom, he paints a balanced picture of the show. And if you’re looking for bass stories that will blow your mind, look no further: This man has seen and done it all.

I really enjoyed Freedom, Randy. There’s tons of cool bass all over it.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“Thanks, man. It was fun. It was a little bit challenging to make during the pandemic, but we did it. I worked at NRG Studios in North Hollywood for part of it, and at my own studio here. It was wild at times, not being in the same room. Jonathan [Cain, keyboards] was in Florida and Arnel [Pineda, vocals] was in Manila, but we did it.”

It doesn’t sound any different to a traditional, studio-recorded album to me.

I used to play upright a lot when I was in high school, too

“That’s because we know each other so well, and we’ve played together a lot over the years. At a certain age and after a certain amount of development and experience, you all know what it is and where it’s going. Also, we all chimed in on writing and co-writing, so we all knew what the intention was, you know what I mean?”

I do, but didn’t you miss that moment when you look at the drummer and they look at you, and you know you’re both going to play something at the end of the bar?

“Oh, I know. I do this anyway, but on this album I played the songs a ton of times over and over in seven different ways, because I was trying to imagine being in a room and getting that feeling.”

If the technology existed so that you could work remotely and the timing would be perfect, with no delay, it would be fine.

“There’s companies coming out with that stuff. One of them is called Sessionwire, and they’re doing some cool stuff that I’m involved with. It sounds cool, and it’s almost close enough to be really workable.”

The company that cracks that is going to make a fortune.

“I know! Let’s dive in with Bass Player. We should be on board with the new Elon Musk.”

What was the gear that you used on the album?

“A four-string Bongo by Music Man, a custom shop Fender Jazz, and a Sadowsky on a couple of songs. I used Ampeg SVTs for a lot of it, a Kemper for most of it, a SansAmp for all of it. Some pick, some fingers, Ernie Ball strings. I was trying to create that sort of Jack Bruce, John Entwistle, John Paul Jones feel, almost like the Acoustic 360 amp that had the fuzz and the tuner in it.”

Does your custom Jazz have different spec?

“Yeah. I still own quite a few older Fenders, but I’m that guy who doesn’t like passive. I love active, so I’m the newfangled guy who wants to be able to dial in what I want to dial in, and dial in how much of it I want.

“I want to be able to oversaturate and overdrive and do what I want to do and have various basses give me three or four or five different tones. You can’t do that with passive, but if you’ve got a Kemper, you’ve got everything you need right there.”

On the recent single, You Got The Best Of Me, you do a load of upper-register stuff at the back end of the song that I really liked.

“Yeah, that’s where the Kemper came in handy, but I think you gotta always start with a great tone. As Clarence ‘Gatemouth’ Brown – the old bluesman I used to play with when I was a kid – used to tell me, the tone is in your hands.”

How old were you when you got started as a bass player?

“I was 14. My brother had a band in my mom’s garage in lovely Louisiana. He was a drummer. In the neighborhood where I grew up, we had what were known as block parties, with a local band in the neighborhood practicing on the front porch of one of the bandmembers’ homes. People would gather around, and the ice-cream truck would come.

“I just fell in love with the bass, and I had a great first teacher, this guy Sammy Thornton. God rest his soul. He was a brilliant guy from Baton Rouge, and he was very old-school – very James Jamerson and Chuck Rainey. I got good beginnings, at a great time, from a master.”

Leon Sylvers – my God, that guy was so dope. He played a Rickenbacker 4001 with Shalamar, he was brilliant. Bootsy Collins, oh my God. Him and Larry Graham, they just leave you speechless

What was your first bass?

“It was a Kingston, and I loved that bass, man – it was great. Then I had a Sears bass. I used to play upright a lot when I was in high school, too. There were so many great bass players around at the time – Jamerson, John Paul Jones, McCartney, and Chuck Rainey of course, but also Niels-Henning Ørsted Pedersen, Miroslav Vitous, Alphonso Johnson, Anthony Jackson, Marcus Miller, Nate Watts, all those guys that came up at the time.

“Also, Leon Sylvers – my God, that guy was so dope. He played a Rickenbacker 4001 with Shalamar, he was brilliant. Bootsy Collins, oh my God. Him and Larry Graham, they just leave you speechless. But you know, there’s some incredible bass players today. Victor Wooten is amazing. I love Mohini Dey, I love Mononeon. My friend Hadrien Feraud is brilliant, too, and so is Pino Palladino. So many great, great players.”

These days, do you define yourself primarily as a bass player, as a record company executive, as a TV personality, or something else?

“Well, that’s funny. I started just as a musician, and later on, I went into the label side doing A&R, and then I went into TV. So I would call myself a creative professional – or a business-minded creative would be a better way to put it, I guess, or a creative entrepreneur.

“In the early days I was just trying to master my craft, which would give me the licence to play with any of the amazing, unbelievable talents that I played with, like Jean-Luc Ponty, like John McLaughlin, like Narada Michael Walden – these giant players.

“I mean, John McLaughlin is like a god. One of my main mentors was John Coltrane, so I always imagined being able to circular-breathe on the bass, like he did on the saxophone. Well, that’s kind of what John McLaughlin did on the guitar. It’s really hard to play like that, which is why they’re still teaching Giant Steps in school. They’ll be teaching it until the cows come home.”

What would circular breathing-influenced bass playing feel like?

“It’s very hard. It’s being able to play at your highest level, melodically and rhythmically, without stopping. It’s still a work in progress.”

What is your philosophy when it comes to good bass playing?

“Once you have your sound, do you listen? And do you use your facility wisely? Because if you don’t, and all you’re doing is showing off, you’re not listening. You’re only listening to yourself, which makes you a terrible ensemble player.

“I’ve spent a lot of time putting bands together for tours, and I would always notice which musicians were actually listening. If you’re just playing and trying to show off, that’s not going to do anybody any good.”

Did you go through that phase yourself?

“Of course. I think all young players do. I tried to play a billion notes a second, and then somebody said to me, ‘Are you feeling any of those notes that you’re playing?’ I was like, ‘Damn, dude, I just got hit hard.’ I had to sit there thinking about it in front of a bunch of people. It took me aback, but I was like, ‘You know what? He’s right. It’s good advice.’

“I grew up loving songs, and for me, in order to love songs, you have to listen to them and hear them – like absorb them, and really digest them, and ask, ‘What is the meaning of the lyric? What is the intention of that bassline?’”

James Brown was a complete performance showman. That’s where a lot of Prince and Michael Jackson’s approach came from

Which performers have impressed you most?

“James Brown, who I met a couple of times. This guy was a complete performance showman. That’s where a lot of Prince and Michael Jackson’s approach came from, which still makes them two of the greatest, but James made it look effortless.

“He thought about every single detail. ‘When I move left, or my hair moves or my hips move, how do I look? How do I stand if I’m gonna hold the mic? How am I gonna hold it? I’m gonna scream to the right and then to the left.’ I mean, just unbelievable.”

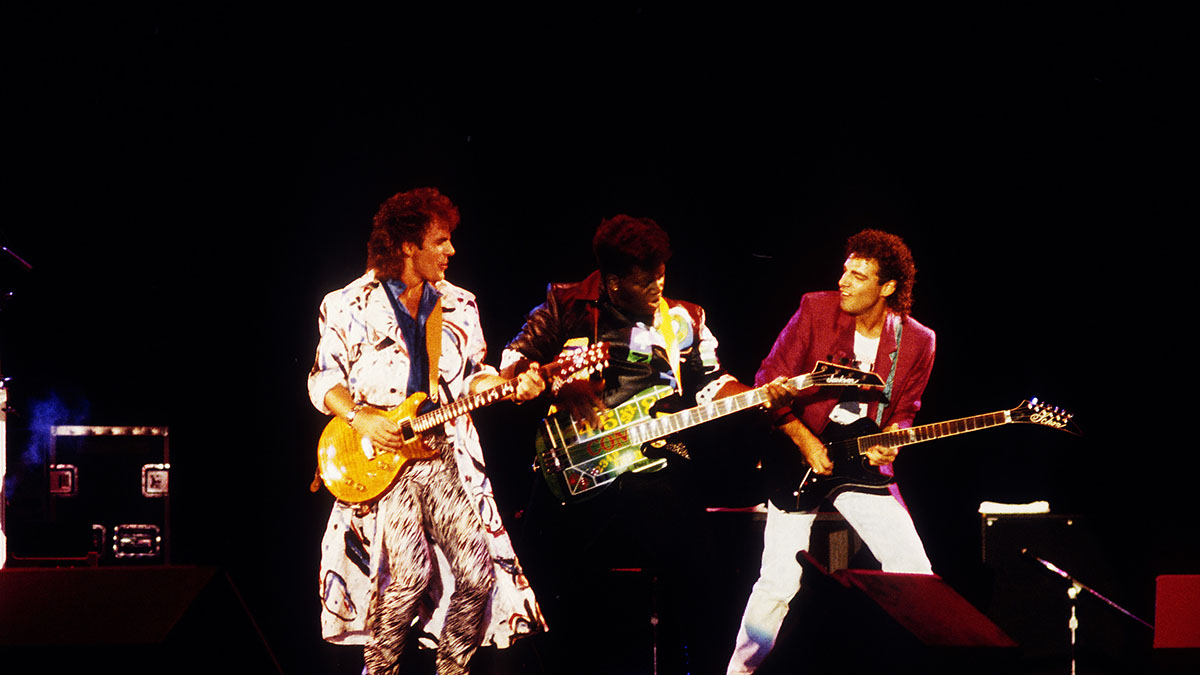

We have a photo of you playing with members of the Grateful Dead in 1989.

“That was an amazing, crazy, wild band, with Jerry Garcia, Bob Weir, Carlos Santana, Joe Henderson, Wayne Shorter, Tony Williams, and Chester Thompson. That was a wild band that was pretty unbelievably amazing. I didn’t quite realize it at the time. But, you know, maybe some of those inebriants helped me not realize that at the time, haha!”

What was your stimulant of choice?

“Whatever the day felt like. What do we feel like today, what color, what size, where should we go today? Wow.”

I love people that can give you the feels, along with the tone and the sound and the playability. Just playing the notes is not enough for me

If someone who wasn’t familiar with your work asked you to recommend one of your recordings, what would you suggest?

“You know, I’ve worked on so many types of records, from Whitney Houston and Madonna to fusion stuff. I loved doing Jumpin’ Jack Flash with Ronnie and Keith and Steve Jordan in 1986 [for the Whoopi Goldberg movie of the same name]. That was fun, because I love the Rolling Stones. And I love the blues, like Christone ‘Kingfish’ Ingram and Marcus King and my boy Eric Gales.

“I love the feels, and I love people that can give you the feels, along with the tone and the sound and the playability. Just playing the notes is not enough for me.

“Anybody can learn to play the notes, and anybody can learn to play fast – but can you play a line with feeling and real intention, so that it reaches out and touches somebody’s soul? I want to make love to the soul, not the mind, like Jaco did.”

Did you ever cross paths with him?

“I crossed paths with him a bunch. I saw him with Wayne Cochran’s CC Riders way back when – the blue-eyed soul band from the south. And then I had one of the greatest times of my life when I was playing with Billy Cobham at the Roxy in LA in 1976 to ’77.

“We played a show attended by my dear friend Chuck Rainey, who I got lessons from at one point in my life. Chuck brought along James Jamerson, Jaco Pastorius, Lenny White, John McLaughlin, Chick Corea, all the Toto boys. And they all came up and sat in!

“It was incredible, man, and then we all played touch football in the street. The day after, I went up to GIT, which had just started, with Jamerson, because he was doing a thing up there. I was just like ‘Wow!’ These guys were all my heroes.”

Fusion was a serious commercial force back then. Why was that?

“It had a much bigger audience than it does today, thanks to guys like Miles Davis and John McLaughlin, who played with Miles. Miles was the firestarter. He made jazz more commercial. He made it sexy. He wore cool clothing, and he was a rock star with electric records like On The Corner, which had two drummers and three bass players that were really pushing the envelope. That’s what started making jazz cool.

“When you think about Alphonso Johnson and how he dressed, and Herbie Hancock at the time with Headhunters and Weather Report, it was very cool. Return To Forever was cool too. I’ll also give massive credit to one of the greatest promoters ever, Billy Graham.

“As a kid in Louisiana, I went to see the Doobie Brothers at the Lakefront Marina in New Orleans, and the band opening for them was the Mahavishnu Orchestra. So to put this in perspective. I’m listening to Black Water by the Doobie Brothers, and these guys come on before that playing Birds Of Fire, my God. My head was blown wide open. Think about that. You don’t have that today. It would be like Snarky Puppy opening for Lil Wayne!”

Would you say you’re playing bass at your best now?

“If you mean, ‘Am I playing with my best wisdom?’ then yes, I would say that part is true. I listen a lot more now than I ever have. It’s probably why I was a pretty good session player, because I think about what the song needs. I think, ‘Does it need me to do this now? What do I want to play? What’s the tone, what’s the sound, what’s the part?’”

I could teach a whole class on listening, with no instruments. I would tell the students, ‘Just listen, and tell me what you’ve heard,’ because I find most people do not listen

What’s your approach to soloing?

“Listen to the melody. Think about what the music is, and think about what the idiom is. If you’re in a funk band, a jazz solo might not work. You can use the whole-tone scale, but it may or may not work. You can use the Mixolydian minor, but that may not work either, so think accordingly. To really play the music, you’ve got to listen.

“I could teach a whole class on listening, with no instruments. I would tell the students, ‘Just listen, and tell me what you’ve heard,’ because I find most people do not listen, or if they do, they only listen to themselves. They think, ‘Okay, I’m learning to play the modes, and I can use this scale here, and I’ll start with a harmonic minor’ and I’ll go, ‘No, you’re not listening – you’re thinking.’”

What’s next for you?

“I’ve been working on a solo record for the last three months. A lot of my favorite players and singers are on it. I’m excited about it – I think you’ll like it. There’ll be some bass and guitar players that you’ll know.”

Did you play bass on it too?

“One of the things I’ve adopted later on in life is that when I’m producing, a lot of the times I’ll get somebody else to play bass, depending on what the music is, because I find it’s hard to perform both roles at the same. It’s kind of fun, you know, seeing how someone else would interpret a bass part, because their approach is always different.”

As a producer, do you prioritize the bass parts because you’re a bass player yourself?

“No, I’m listening to the whole band. See, as a producer, you have to listen to everything, because you’re trying to get a message out to someone. It can’t just be about the bass. That’s why I don’t play bass when I’m producing. If I don’t like what has been recorded, I’ll go back later and replace it or add to it or whatever, but I’m trying to get the right perspective.

“What’s the intention? What’s the song supposed to say? And more importantly, what are you supposed to feel while you listen to it? Am I trying to make you dance? Am I trying to make you sad? Am I trying to make you hopeful? What am I trying to give you?

“Listen to Santana – how does that make you feel? Listen to Bartok or Beethoven or Bach or Prokofiev. What are they trying to give you? What am I supposed to get from Bootsy’s Rubber Band? What’s he trying to give me?”

Your career in A&R presumably gave you added perception when you became a producer.

“Yeah, because it forced me to understand more about what it means to become a successful songwriter and a successful producer. It actually forces you to have to view it from 30,000 feet and become truly objective. It’s not about you. It’s all about the song.”

Is A&R a tough business?

“It’s really hard, because everybody’s got an opinion, but is it the right opinion? Are you being honest with yourself? Are you being honest with the artist? Are you signing and developing the right artists? Is their music good, and what does good actually mean? Is it gonna sell? Is it going to make the company money?

“There’s a lot that goes into it, because anybody can make music. That’s actually part of the problem today. One of the downsides of social media and YouTube is that there’s no arbiter of tastes, so you have to weed through a lot of garbage to find the good shit.”

Well, that leads me to American Idol. A lot of people don’t trust music from TV talent shows. Are they wrong to feel that way?

“Yeah. They just don’t realize what American Idol was about. See, Simon Cowell and I were both A&R guys at the time of being judges on Idol. We weren’t stars, we were just A&R guys. Our day job was about finding and developing talent and making it happen, and what was American Idol about? It was a show about finding and developing talent and making it happen.

“Basically, it was a glorified A&R show. It gave us marketing, it gave us research, and we would take somebody that you didn’t know, and they would leave the show with 10 million people as their audience. When we put their record out, we could go to 10 or 15 percent of that audience to market and sell to, so now a nobody has a million and a half people that actually give a shit.

“Look at Kelly Clarkson, who’s talented and sold seven-million copies: 40 million people voted for her. Now, if 40 million people knew about Mohini Dey and voted for her, that would be a different conversation. So American Idol was really a marketing tool, although the public will never see that.”

That makes sense.

“Yeah. We saw that it was becoming hard at that time to break new artists. I was at MCA Records, and you could put Blink-182, Mary J. Blige or whoever on any TV show – Letterman, Carson, Leno – and you’d spend a bunch of money doing it, just to sell another 10,000 records. We saw all that dwindling at the time, so our question was, how do you bring a new artist out?”

In 2022, has the talent-show format been replaced by YouTube or TikTok or one of those platforms?

“TikTok has definitely helped a bit, but as I said, the real issue is that there’s no arbiter of taste. So on TikTok, you gotta listen to 20,000 horrible singers to hear one good one.

“At least on TV talent shows, you may only have to hear 500 bad ones to get to the good ones. It’s the same thing with YouTube. Nobody’s saying ‘Don’t put that song out’. You and I could be in a pub right now, and everybody in the pub could release 10 songs. Forget the talent level. That’s the problem.”

Having been known as a musician beforehand, how did it feel to make the transition to being a household name when American Idol got popular?

“It was a little weird. I’d be queued up at a store, and people would walk up and start talking to me like I was their best friend. I’d think, ‘I don’t even know you,’ but they’d talk for hours, asking me ‘What do you think about so and so?’ But we were in people’s homes twice a week, so I understood it.”

You don’t miss the show?

“Well, now I’m on Name That Tune, which is like an old-school game show. I don’t miss judging artists, because I did it for so long. But we’re developing another show along those lines, and I think it’s the next new wrinkle. It’s a music show, but it’s a little bit different – I think people will dig it.”

- Freedom is out now via BMG.

Joel McIver was the Editor of Bass Player magazine from 2018 to 2022, having spent six years before that editing Bass Guitar magazine. A journalist with 25 years' experience in the music field, he's also the author of 35 books, a couple of bestsellers among them. He regularly appears on podcasts, radio and TV.