Ritchie Blackmore: "It's much easier to flow across the strings on a Gibson. Fenders have more tension, so you have to fight them a little bit"

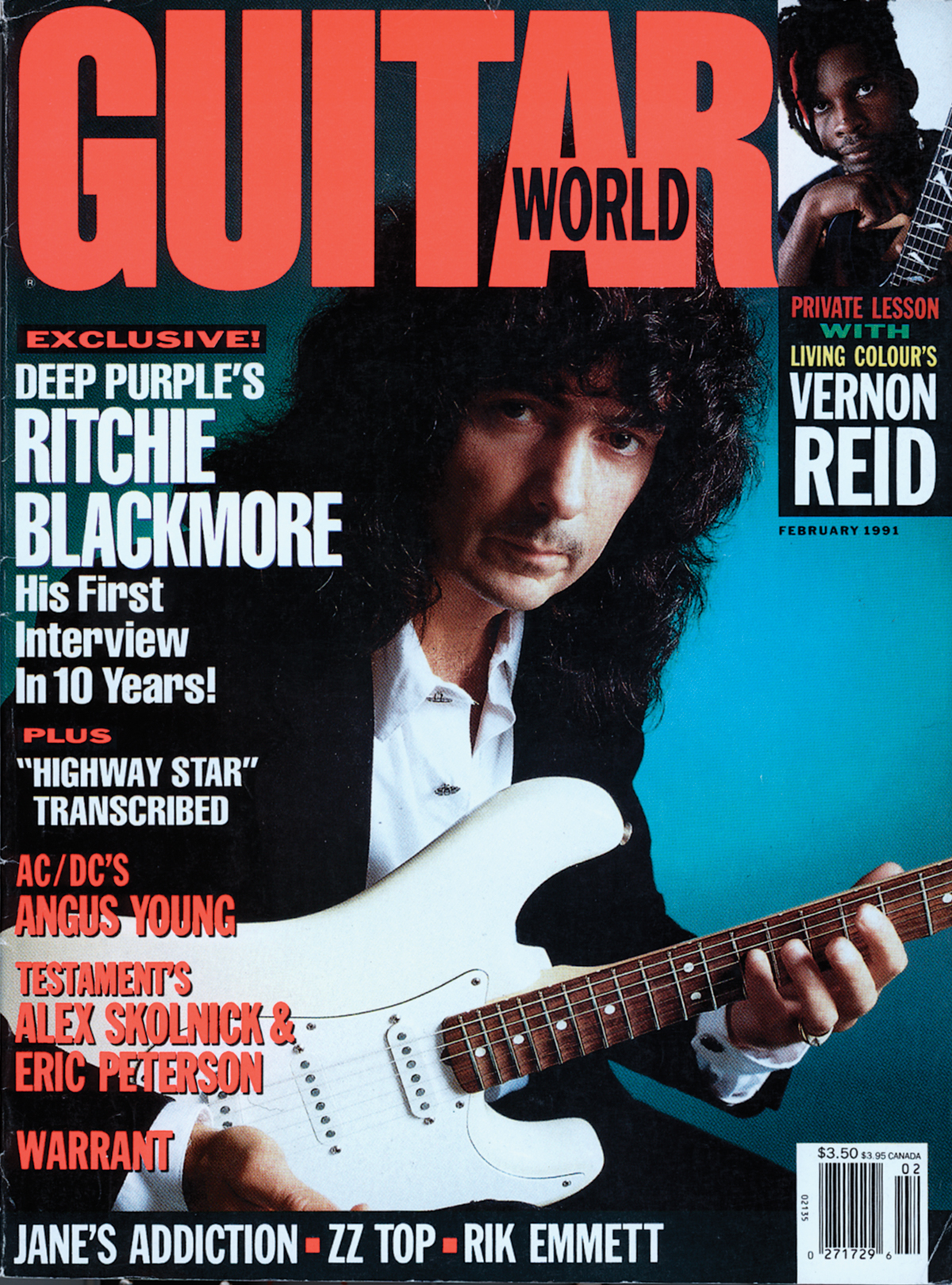

In this classic 1991 GW interview, the Deep Purple guitar hero chats about his whammy bar violence, his switch from Gibsons to Strats, and why he thinks Smoke on the Water has endured as a rock classic

This interview with Ritchie Blackmore of Deep Purple appeared in the February 1991 issue of Guitar World.

It’s a cold, rainy night in Connecticut. Executive Editor Brad Tolinski and I are in the lobby of a fine hotel, waiting to meet Ritchie Blackmore.

The veteran guitarist has, in his infinite mercy, granted us a rare interview. (Perhaps the imminent release of the new Deep Purple album, Slaves and Masters, featuring Purple's latest member, Joe Lynn Turner, has something to do with this.)

At the moment, Blackmore is dining with some friends; he is to join us at the conclusion of his meal. Tolinski and I are a bit apprehensive. Blackmore's irascibility is legend, as is his antipathy toward the press. To make matters worse, even some of those close to the star have warned that he could become "troublesome."

I feel like I'm about to meet Darth Vader. As I examine my tape recorder to ensure that everything is in working order (I'm always worried that it will break down), a grim scenario plays itself repeatedly in my brain: The interview has commenced. I ask my first question – "How does this version of Deep Purple differ from past formations?" Blackmore stares at me, his features growing black with rage. “How dare you ask me that?” he barks.

"Take that!" He bops me over the head with a white Strat, which falls all around me in splinters. The angry man rises and stalks out. End of interview. I return to an uneasy reality, but calm myself with the thought that my guitar hero can't possibly be such an ogre.

Then I remember that as a youth, Blackmore had a penchant for throwing eggs, tomatoes and four-pound bags of flour from moving vehicles at passersby (with particular preference, presumably, for elderly women in wheelchairs.)

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

At last, a member of Blackmore's entourage comes by to say that the great one is ready. We enter the dimly-lit dining area to the accompaniment of mellow piano music, diners' chattering and dishes clattering, and seat ourselves. After a few moments, we are joined by Ritchie Blackmore.

He looks great – better than he did 10 years ago, which is far more than can be said of most longtime rockers. As usual, he's dressed in black, except for a white ruffled shirt that makes him look like a French nobleman. He grasps our outstretched hands (a good sign, I think) and we introduce ourselves.

Blackmore seats himself, and orders a beer. "Are you ready?" I ask, and Blackmore nods his assent. But before I can ask the first question, he points at my tape recorder and in thick British tones says, "By the way, that's not on." 'Oh no,' I think. 'The tape's busted!' My worst fears, realized.

Brad stares at me, horror etched on his features. I examine the contraption, but it seems to be running smoothly. I turn to Blackmore, a bit befuddled, and insist, "It's moving. It's on.” "Just checking," he says slyly. And with that, the interview commences.

Within a few dizzying moments he demonstrates that, his reputation notwithstanding, he is a hell of a nice guy, funny – a great dude to hang out with. He even performs a magic trick, changing a nickel into a quarter before our very appreciative eyes. Two hours pass.

The restaurant 's proprietor stops by to announce, "Closing time." I wholeheartedly thank Ritchie for being so cooperative.

"Thank you for being so attentive," says this amiable bane of rock journalists.

How does this edition of Deep Purple differ from past formations?

"Musically, I would say the singer doesn't drink as much. [laughs] But seriously, the older I get, the more I want to hear melodies. We really worked hard on constructing good, memorable songs and interesting chord progressions. That's what excites me at the moment.

"It also helped that our new singer, Joe Lynn Turner, writes and sings great melodies. With Joe, we didn't have to rely as much on heavy riffs. When I was 20, I didn't give a damn about song construction. I just wanted to make as much noise and play as fast and as loud as possible."

As a guitarist, what were you looking to do differently on this new record? For instance, the solo on King of Dreams has an exotic tinge that doesn't appear in any of your previous work.

"I wanted that solo to evoke a certain mood. It isn't meant to be a pointless exercise in speed; that's why it's very sparse. I was trying to make it an extension of the vocal melody and have it express something that was connected to the bloody song. I didn't want to just show off some trick I'd learned at the music store on Saturday morning."

When writing, or when engaged in preproduction for an album, do you work solos out in advance?

"I never work out my leads. Everything I do is usually totally spontaneous. If someone says, 'That was good; play that again,' I'm not able to do it. The only solo I've committed to memory is Highway Star [from 1972's Machine Head]. I like playing that semitone run in the middle."

[Keyboardist] Jon Lord plays more textures, rather than actual lines, on this new album.

"Jon likes to see what I'm going to do and he enhances that. He's not a leader; he likes to follow."

Is that why your relationship has lasted so long?

"Yes, because we don't tread on each other's toes."

Let's go back to the beginning of Deep Purple. How did you and Jon meet?

"I met him in a transvestite bar in '68, in Hamburg, Germany. [laughs] Back in the late Sixties, there were few organists who could play like Jon. We shared the same taste in music. We loved Vanilla Fudge – they were our heroes.

"They used to play London's Speakeasy and all the hippies used to go there to hang out – Clapton, the Beatles – everybody went there to pose. According to legend, the talk of the town during that period was Jimi Hendrix, but that's not true. It was Vanilla Fudge.

"They played eight-minute songs, with dynamics. People said, 'What the hell's going on here? How come it's not three minutes?' Timmy Bogert, their bassist, was amazing. The whole group was way ahead of its time.

"So, initially we wanted to be a Vanilla Fudge clone. But our singer, Ian, wanted to be Edgar Winter. He'd say, 'I want to scream like that, like Edgar Winter.' So that's what we were – Vanilla Fudge with Edgar Winter!"

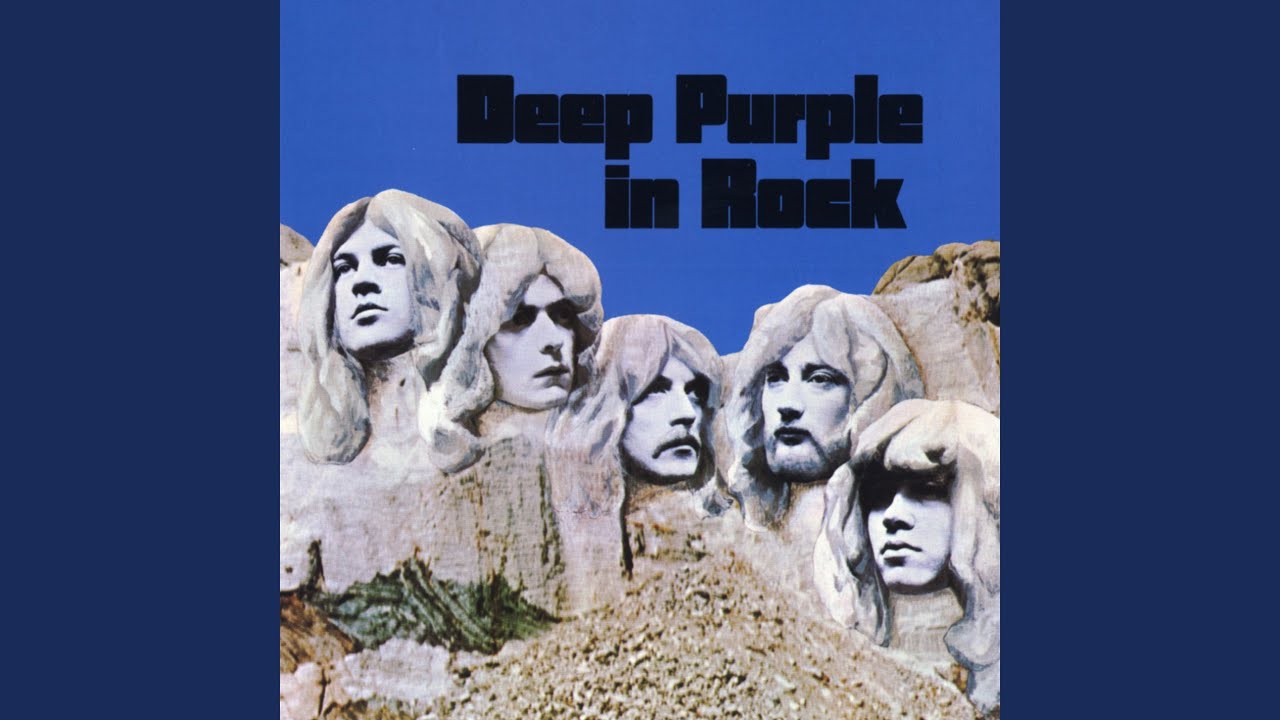

After your breakthrough record, Concerto for Group and Orchestra [1970] with The Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, your playing took a more aggressive turn. In Rock [1970] almost became the blueprint for all subsequent Purple records.

"I became tired of playing with orchestras. In Rock was my way of rebelling against a certain classical element in the band. Ian Gillan, Roger Glover and I wanted to be a hard rock band – we wanted to play rock and roll only. So off we went in that direction.

"I felt that the whole orchestra thing was a bit tame. I mean, you're playing in the Royal Albert Hall, and the audience sits there with folded arms, and you're standing there playing next to a violinist who holds his ears every time you take a solo. It doesn't make you feel particularly inspired."

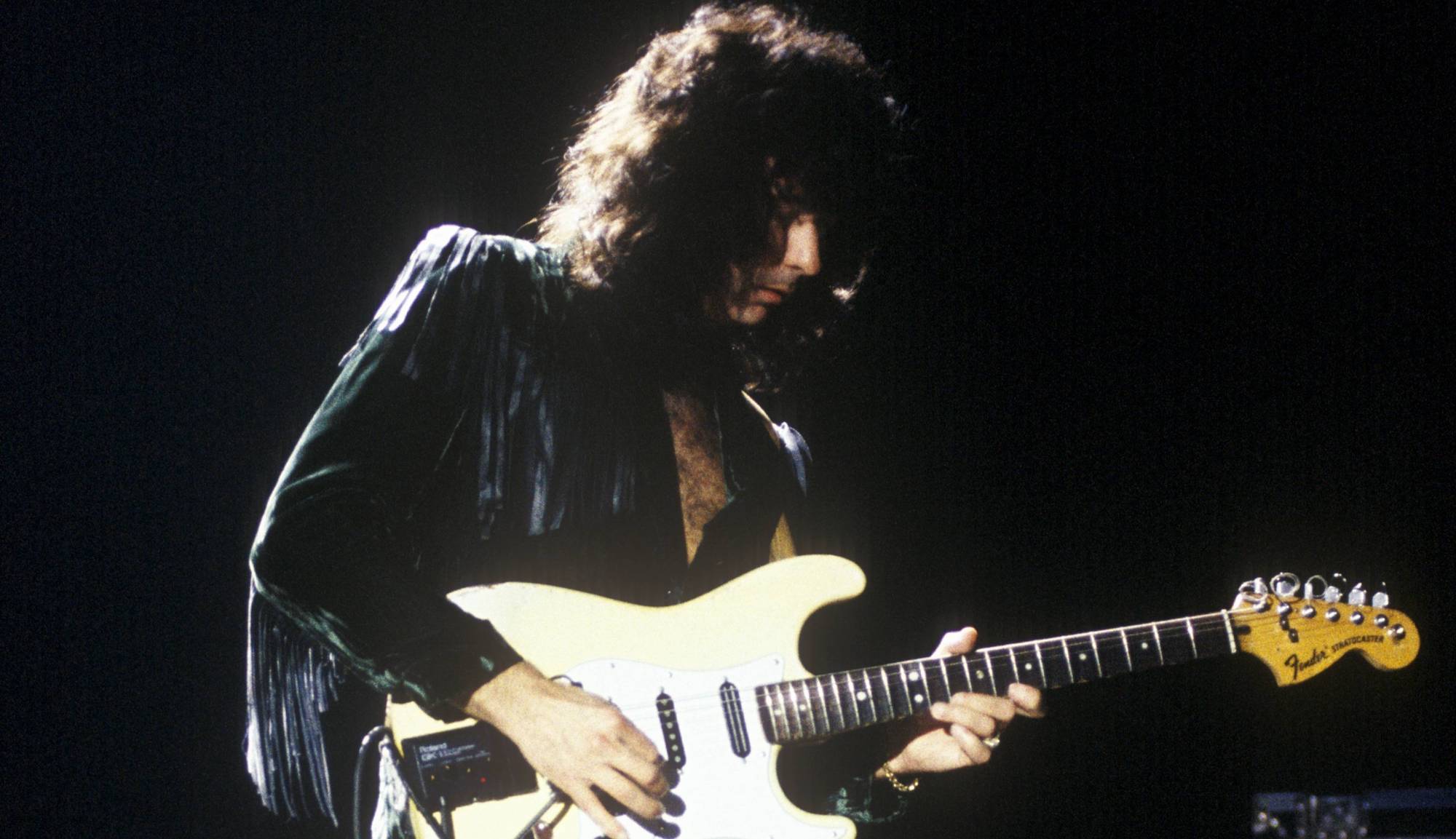

You started using the vibrato bar extensively on In Rock.

"Yes, that's right. I'd seen the James Cotton Blues Band at the Fillmore East, and the guitarist in the band played with the vibrato bar. He got the most amazing sounds. Right after seeing him, I started using the bar. Hendrix inspired me, too."

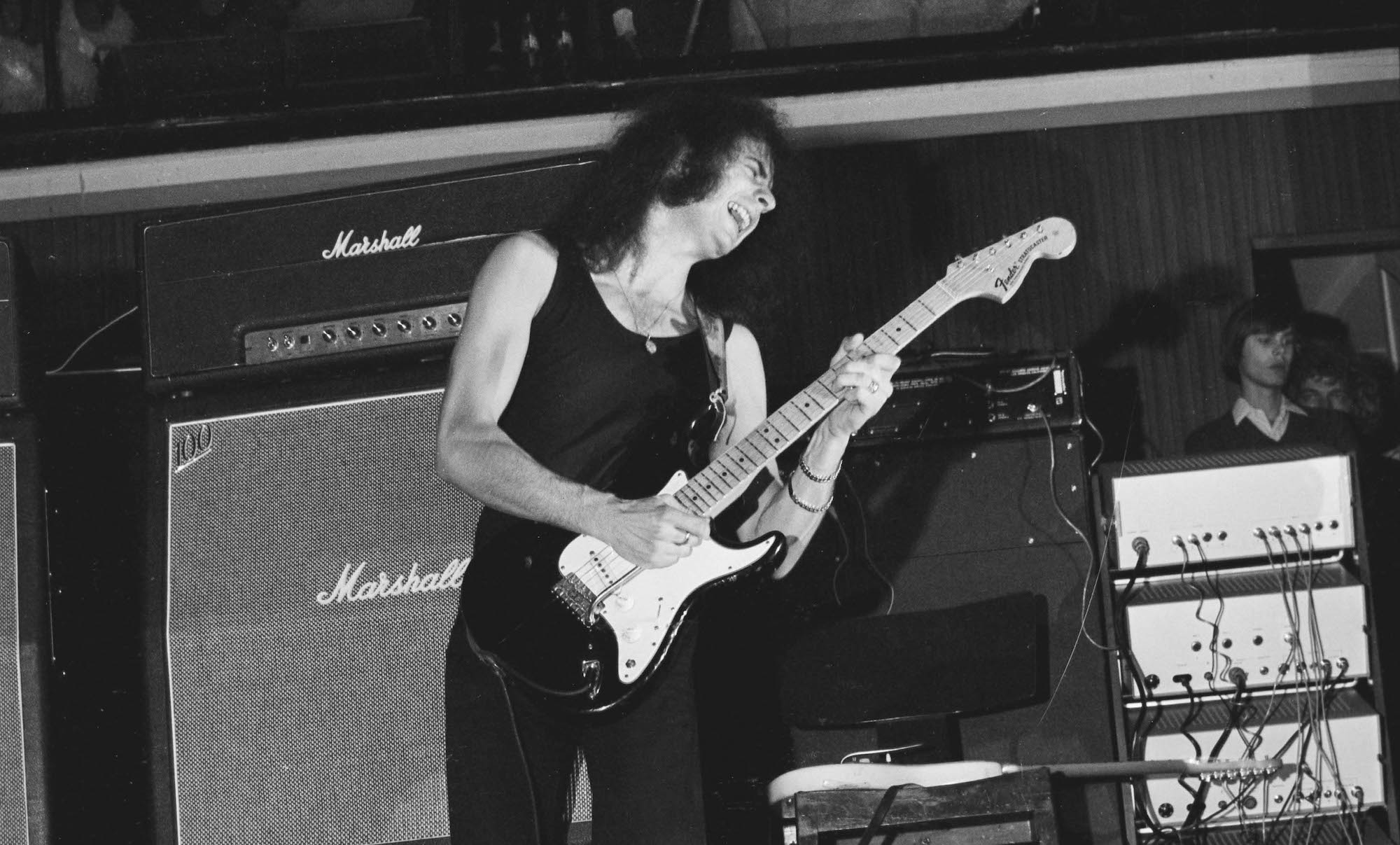

You used to give the whammy bar a real workout.

"I went crazy with it. I used to have quarter-inch bars made for me because I'd keep snapping the normal kind. My repairman would look at me strangely and say, 'What are you doing to these tremolo bars?'

"Finally, he gave me this gigantic tremolo arm made of half-an-inch of solid iron and said, 'Here. If you break this thing, I don't wanna know about it!' About three weeks later I went back to the shop. He looked at me and said, 'No – you haven't.' And I said, 'Yes, I have.'

"In graphic detail, I explained to him how I would twirl the guitar around by the bar, throw it to the floor, put my foot on it and pull the bar off with two hands. He was a bit of a purist, so he wasn't amused."

There is a lot of unusual noise during the final solo of Hard Lovin' Man [In Rock]. Is that you, throwing your guitar around in the studio?

"If I remember right, I was knocking my guitar up and down against a door in the control room. The engineer looked at me oddly. He was one of your typical, old-school engineers. Like my repairman, he wasn't amused, either."

Did you ever try a locking-nut tremolo system?

"No. I don't use the twang bar anymore. It's become too popular."

Between In Rock and Fireball [1971], you switched from Gibsons to Fender Strats. How did that affect your playing style?

"It was difficult, because it's much easier to flow across the strings on a Gibson. Fenders have more tension, so you have to fight them a little bit. I had a hell of a time. But I stuck with the Fenders because I was so taken with their sound, especially when they were paired with a wah-wah."

Around Fireball and Machine Head [1972], your playing took on a blues and funk edge. Did Hendrix have anything to do with that?

"I was impressed by Hendrix. Not so much by his playing, as his attitude – he wasn't a great player, but everything else about him was brilliant. Even the way he walked was amazing. His guitar playing, though, was always a little bit weird. Hendrix inspired me, but I was still more into Wes Montgomery. I was also into the Allman Brothers around the time of those albums."

What do you think of Stevie Ray Vaughan?

"I knew that question was coming. His death was very tragic, but I'm surprised everybody thinks he was such a brilliant player when there are people like Buddy Guy, Albert Collins, Peter Green and Mick Taylor – Johnny Winter, who is one of the best blues players in the world, is also very underrated. His vibrato is incredible.

"Stevie Ray Vaughan was very intense. Maybe that's what caught everybody's attention. As a player, he didn't do anything amazing."

How did you develop your own unique finger vibrato style?

"In my early days, I never used finger vibrato at all. I originally carved my reputation as one of the 'fast' guitar players. Then I heard Eric Clapton. I remember saying to him, 'You have a strange style. Do you play with that vibrato stuff?' Really an idiotic question. But he was a nice guy about it.

"Right after that I started working on my vibrato. It took about two or three years for me to develop any technique. Around '68 or '69 you suddenly hear it in my playing."

I've noticed that your rhythm parts aren't always played with a pick.

"That's from being lazy. It's like Jeff Beck – when he can't find a pick, he just plays with his fingers. You know how it is. You're watching television and you can't find a pick, so you just play with your fingers.

"Even on something as simple as the riff to Smoke on the Water, you'd be surprised at how many people play that with down strokes, as though it were chords. I pluck the riff, which makes a world of difference. Otherwise, you're just hitting the tonic before the fifth."

Why do you think that, of all your work, Smoke on the Water is so enduring? The riff is the rock equivalent to the opening of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony.

"Simplicity is the key. And it is simple – you can still hear people playing it at music stores. I never had the courage to write until I heard I Can't Explain and My Generation. Those riffs were so straightforward that I thought, 'All right, if Pete Townshend can get away with that, then I can, too!'"

What did you think of Tommy Bolin when he took your place in Deep Purple, following your '74 departure?

"I originally heard him on Billy Cobham's Spectrum album, and thought, 'Who is this guy?' Then I saw him on television and he looked incredible – like Elvis Presley. I knew he was gonna be big. When I heard that Purple hired him I thought it was great. He was always so humble.

"I remember he would always invite me out to his house in Hollywood to see his guitar. One day I went to his place. I walked in and tried to find him, but no one was around. There were no furnishings – nothing. I stayed there for 10 minutes before he finally appeared.

"He showed me his guitar, and the strings must have had a quarter-inch of grime on them, as though he hadn't changed them in four years. I asked him when was the last time he'd changed strings, and he said very seriously, 'Gee, I don't know. Do you think I should change them?'"

Following your departure from Purple, you drifted back to a slightly classical direction in Rainbow.

"I was never sure what I wanted to be. I found the blues too limiting, too confining. I'd always thought – with all due respect to B.B. King – that you couldn't just play four notes. Classical, on the other hand, was always too disciplined. I was always playing between the two, stuck in a musical no-man's land."

Did you ever toy with the idea of playing strictly classical music?

"Yes. I would love to go back to the 1520s, the time of my favorite music. A few of my friends in Germany have a very authentic four-piece, and they play medieval music. I've always wanted to play with them, but it hasn't panned out yet. But in general, I'm not good enough, technically, to be a classical musician. I lack discipline.

"When you're dealing with classical music, you have to be rigid. I'm not a rigid player. I like to improvise."

The song Stargazer, from the second Rainbow album [Rising, 1976], has a strong classical feel. How did you come up with that one?

"That was a good tune. I wrote that on the cello. I had given up on the guitar between '75 and '78. I completely lost interest. I was sick of hearing other guitar players and I was tired of my tunes. What I really wanted to be was Jacqueline du Pré on cello. So I started playing cello."

Did you ever record with a cello?

"Yes, just on a small backing track – I can't remember on what. But you have to give your whole life to a cello. When I realized that, I went back to the guitar and just turned the volume up a bit louder."

Was there anything you learned from the cello that you applied to the guitar?

"Not really. The cello is such a melancholy instrument, such an isolated, miserable instrument. But it was an appropriate choice for me at the time, because my girlfriend had left me and I was going through this miserable phase."

What do you think of Yngwie Malmsteen? He's often credited you as an influence.

"He's always been very nice to me, and I always get on very well with him. I don't understand him, though – his playing, what he wears. His movements are also a bit creepy. Normally you say, 'Well, the guy's just an idiot.' But, when you hear him play you think, 'This guy's no idiot. He knows what he's doing.'

"He's got to calm down. He's not Paganini – though he thinks he is. When Yngwie can break all of his strings but one, and play the same piece on one string, then I'll be impressed. In three or four years, we'll probably hear some good stuff from him."

What do you think of tapping?

"Thank goodness it's come to an end. The first person I saw doing that hammer-on stuff was Harvey Mandel, at the Whisky a Go Go in '68. I thought 'What the hell is he doing?' It was so funny [laughs], Jim Morrison was carried out because he was shouting abuse at the band.

"Jimi Hendrix was there. We were all getting drunk. Then Harvey Mandel starts doing this stuff [mimes tapping]. 'What's he doing?' everybody was saying. Even the audience stopped dancing."

Obviously, Eddie Van Halen must have picked up a few of those things. What do you think of him?

"It depends on my mood. He is probably the most influential player in the last 15 years 'cause everybody's gone out and bought one of those, what does he play, Charvel, Carvel... Kramer, with the locking nut. Yes, with the locking nut! And everyone's gone hammer-on crazy!

"So he's obviously done something. He's a great guitar player, but I'm more impressed by his recent songwriting and keyboard work. I think he's going to be remembered – he could be the next Cole Porter."

How do you feel about your own guitar hero status?

"It's funny to find myself in that position, because when I first came to America I thought, 'Why go to America when they have these fantastic players?' I was brought up on [pedal steel great] Speedy West and [country guitarist] Jimmy Bryant, people like that.

"When I was 13 years old, I couldn't believe how good they were. I thought, 'When I go to America, I'm going to get killed.' Everything changed when we had a hit with Hush. I found people saying, 'Oh, you play guitar really well.' I'd say, 'How can you say that when you've got these guys in Nashville who just tear me apart?' I still say it. If you tune into Hee Haw you'll see these guys who are absolutely amazing.

"Jeff Beck once told me that he went to Nashville to do a record. While he was in the studio, this guy who was sweeping up asked him, 'Can I borrow your guitar for a second?' Jeff said, 'Oh, of course.' The guy started playing and completely blew Jeff away. He left soon after that. Thank goodness all those amazing players stay in Nashville!"

Has your approach to sound processing changed? Have you checked out any of these multi-effects racks?

"I don't put myself on Jeff Beck's level, but I can relate to him when he says he'd rather be working on his car collection than playing the guitar. I'm enjoying other things in life, but when I do pick up the guitar, I want to simply plug into a loud amplifier, and that's it.

"Maybe if I were 20, I'd pay more attention to equipment trends; at 45, you start to go in other directions. I get turned on by soccer shoes; I listen to Renaissance music – those are the things that really stir my soul. There are so many effects and new guitar players. I can't comprehend it all. When you hear them, you suddenly realize that they all sound the same – like Eddie Van Halen, speeded up."

Do you have a home studio?

"No, I don't. It's gotten out of hand – everybody has their own studio. I'd rather write something on the spur of the moment, while doing a formal recording. I believe in inspiration."

What does the future hold for you?

"I'm very moved by Renaissance music, but I still love to play hard rock – though only if it's sophisticated and has some thought behind it. I don't want to throw myself on a stage and act silly, 'cause I see so many bands doing that today.

"There's a lot going on today that disturbs me – so much derivative music. Where are the progressive bands like Cream, Procol Harum, Jethro Tull or the Experience? I could go on, but we have to live with it."

![Deep Purple - Burn [Ritchie Blackmore's solo] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/WAW9DfqKQro/maxresdefault.jpg)