Robben Ford: “Tone has always been number one to me. It needs to sound good first – otherwise, who cares what the notes are?”

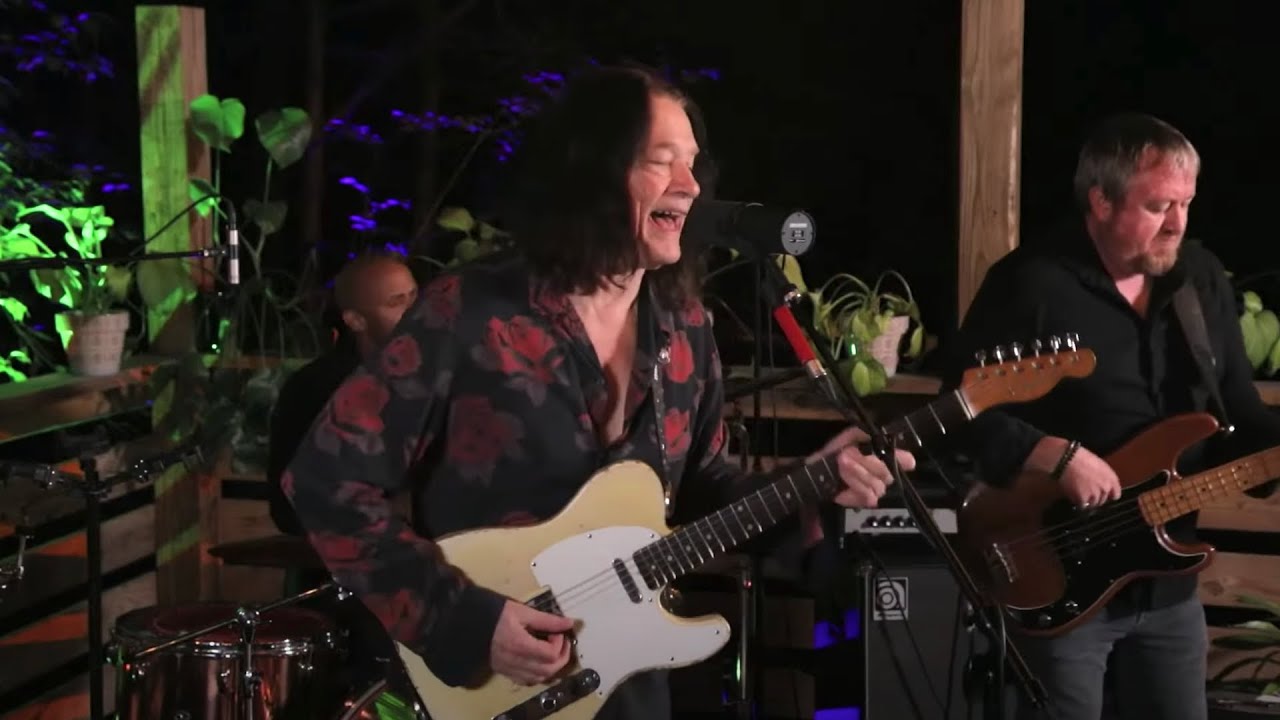

A revered guitarist who has played for legends such as Miles Davis and Joni Mitchell, and created a series of brilliant solo albums, Robben Ford sits down to share his wisdom...

Guitarist, singer, songwriter and occasional saxophonist, Robben Ford got his break in 1969 when, aged 18, he and his band were recruited to back blues harmonica maestro Charlie Musselwhite.

Ford went on to play guitar for Joni Mitchell with elite jazz fusion collective, The L.A. Express, to play sideman for Miles Davis, Bob Dylan, George Harrison, and to grace records by legendary figures such as Michael McDonald, Bonnie Raitt and Larry Carlton. But it’s through his solo career that Ford’s own legend has truly grown.

With the heart and soul of a bluesman and the brain and fingers of a jazzer, he has a back catalogue packed with high-grade blues/rock records such as The Inside Story, Talk To Your Daughter and – featuring his must-hear ’90s group The Blue Line – the Grammy-nominated Mystic Mile and Robben Ford And The Blue Line.

Now 69, Ford’s on a hot streak through recent acclaimed releases Into The Sun, Purple House and The Sun Room, and he continues with Pure, a masterclass in blues, funk and – via the title track – exotic, world‑tinged guitar alchemy.

He shares a lifetime of musical wisdom online at Robben Ford Guitar Dojo, and speaks to Total Guitar from his Nashville home to offer advice on how to be the best musician you can be...

With both melody and lyrics, that first line is all-important

“I’m pretty good with melodies, they come spontaneously to me. The opening line of Pure has a lot of chromatics in there, and I just sort of played it... As far as I’m concerned, it’s the same way writing melodies and lyrics – when you have your first line, basically the song is there. It’s there to be written, you just have to follow that musical thread out.”

Make tone your first priority

“Tone has always been number one to me. It needs to sound good first, otherwise, who cares what the notes are? My first musical hero was Paul Desmond [sax player for The Dave Brubeck Quartet; writer of Take Five]. Take Five is beautiful – that sound just went into my body.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“With the guitar, when I heard The Paul Butterfield Blues Band I wanted to play like [guitarist] Mike Bloomfield, and to sound like him. The two go hand in hand. Bloomfield was a playing a ’63 Telecaster. Around 1965 I went into a music store and bought a Guild Starfire III.

“It was semi-hollow – far from a Tele! – but when I played it, it sounded like Mike Bloomfield to me. There must have been a connection that you bring out of the guitar. I felt like, ‘Wow, I’m getting the sound I want!’”

Learn your chords, then the scales to solo over them

“I learned chords out of Mickey Baker’s [classic 1955 instructional book] Complete Course in Jazz Guitar. They’re all on page one and two. I applied those chords directly to Chicago blues music, which is what I was playing at the time with Charlie Musselwhite. Instead of just the straight-up nine or seven chords, I started using altered chords.

“Charlie liked jazz and didn’t mind hearing these behind him. I was still just playing pentatonic and blues licks, so then I learned the scales that go over those chords. I just banged away at it the same way I had the pentatonic scale – no teachers, no lessons. I just tried to play something that sounded like something I’d heard.

“I have big ears, you know? I’d listen to what I’d heard other people play and would start to recognise the scale, because I knew it now. I can’t play jazz like great players like Kurt Rosenwinkel can, but I have enough of an understanding of harmony, chords and scales. For me, it’s more spice to my blues playing.”

Work on your rhythm playing (and listen to Hendrix...)

“In the beginning, I was a bad rhythm guitar player, but The Blue Line was usually a trio – I was the only soloist, I was singing everything and I had to be the chordal instrument, so I started to become a better rhythm player. For my record Supernatural [1999] I was listening to Hendrix for inspiration, especially May This Be Love [from Are You Experienced].

“I started playing something on the guitar like that; it felt pretty natural to do, and that became a really important thing from that point on. My influence up to that point had been straight-up blues or jazz, but I started really getting into that more fluid, strumming, Hendrix style of rhythm playing. I just love it – it’s so guitaristic.”

Approach music like a composer and an arranger, not just a guitarist

“I’ve always thought like a composer. You have to have a song, or you’ve got nothing to play! I learned that in the mid-’70s, through my early work with [fusion sax great] Tom Scott – an excellent composer – and The L.A. Express, and Joni Mitchell.

“I learned through them that if this instrument’s doing this, then you don’t do that [on guitar], as it’s already being done. If this instrument’s playing low, then you play something high. I learned that in my 20s, thankfully, and always carried it with me. It’s something people don’t always think about, young guitar players especially.”

Right hand, left hand...

“I never really thought a lot about the right hand; it just sort of happens. I used to play a lot more with my fingers than I do now, but I’ve gone back to using the pick more. Early on, I did practise back and forth [alternate] picking, up and down, but then I’ll play things differently – sometimes I’ll start with an upstroke, sometimes a downstroke.

“I don’t always know what’s going to happen! As far as my left hand technique, I use a lot of hammer-ons and pull-offs, and I use all four fingers. That’s something some people skip – they'll use just three fingers, but I made an effort to use all four.”

When playing with another musician, be sure to listen

“I’ve sat down with another guitar player to jam in a teaching situation, and when they start playing that person is louder than I am, and not listening to me at all. I understand that, because you’re just full of energy and trying to do something. So I might simply ask them: ‘Are you listening to me at all?’

“Make sure you’re listening to what’s around you. It does take time to learn, and you have to be in situations to learn it. I was lucky being with Tom [Scott] and all those studio musicians. They knew how to accompany, they were amazing.”

Your equipment reflects your ‘voice’

“I have a 100-watt Dumble Overdrive Special, and a 2x12 speaker cabinet. I’d actually just bought the Dumble when I worked with Mike [Michael McDonald, in the mid-’80s]. I’d go to recording dates with that, because that’s what I did, and it took me a very long time to learn, ‘Okay, this is this type of music and requires this or that guitar, and a smaller amp in the recording studio!’ But I’ve been a solo artist for such a long time, people usually call on me to be myself. I have a voice, you know?

“On White Rock Beer... 8 Cents [from Pure] that’s the Dumble cranked up with the ’54 Les Paul Gold Top converted to ’59 specs. Best PAFs I ever heard, flametop on it and everything. I use a Paul Reed Smith on Blues For Lonnie Johnson, and the solo on Dragon’s Tail is done on my 1965 Epiphone Riviera.

“The Riviera and my 1960 Tele were my road guitars for about two and a half years, but I’ve found myself moving back toward the Les Paul. The melody to Pure is played on a cool ’64 SG, plugged into a 15-watt Little Walter ‘King Arthur’ head and a single 12 – it’s like a Tweed, but it’s cranked. That’s why that melody is just kind of screaming out of there. I do like to play loud!”

Be generous with your knowledge

“It makes me very happy if I’m teaching a masterclass and I see the light bulb go off over somebody’s head. Somebody might tell me, ‘I never understood the modes until just now’, just because of how I put it. Theory can seem so mysterious. And whenever I hear somebody who can really play the guitar, that's very exciting. If I can be of service, I’m happy to help…”

Robben Ford's theory wisdom

1. Altered five chords

The strongest harmonic pull in any progression is from the V to the I chord, and this solid sense of resolution means you can get creative with the V chord itself and add jazzy ‘altered’ notes, without jeopardising the music’s flow.

In jazz you can treat any dominant 7th chord (ie chords with a major 3rd and flat 7th) as the V chord of its corresponding I. So, as C is the fifth note in the scale of F, so C7 can be treated as the fifth chord of F.

“So if you're playing a blues in the key of C,” Ford explains, “the C can become the five chord for your next chord, the F, so you just treat the C as an altered five chord, and then treat the five chord [G7] as an altered five chord [of C]. Traditional blues does not do that. It’s that altered five chord where the jazz influence really comes in.”

2. The double-diminished scale

“I use the double-diminished scale all the time,” says Ford, “and it's something I still work at. It's become a big part of my thing, but you don't hear much about it with anybody else.”

Also known as the half/whole diminished scale, this tasty run contains eight notes in half-step/whole-step intervals, so in C it’s: C DbD# E F# G A Bb. Notice it contains the notes of the C7 triad (C E Bb), the C’s fifth (G) and sixth (A), but along with these it gives you ‘altered’ notes: Db (the b9 of C), D# (the #9), F# (the #11).

Try adding a few licks from this scale into your blues, particularly when moving from the I to the IV chord (in C, from C7 to F7) and in your turnaround from V to I (G7 to C7). Those non-diatonic, ‘altered’ tones will give your blues a dash of jazz spice.

3. The altered scale

The altered scale (aka Superlocrian mode) is the seventh mode of the melodic minor scale, and because its packed with flats and sharps, it’ll work over altered chords.

“Over an altered five in a blues,” says Ford, “you can use the melodic minor, but a half step up. So if you’re playing over a G altered chord, you’d play Ab melodic minor (Ab Bb B C# D# F G).” Just remember G would be your root note here.

4. The pentatonic scale as an ‘altered’ scale

Ford notes that the good old minor pentatonic scale (in C: C Eb F G Bb) also conceals altered notes, i.e. tones that aren’t in the standard chords played in a I-IV-V blues: “If you're playing the C pentatonic scale over the G7 chord, and you play the minor third of C [Eb] and then the flat seven [Bb], you've just played the altered fifth and the raised nine of the G chord. So if you’re playing the pentatonic scale in the key of C against a G, before you even know it you’re playing altered tones.”

Grant Moon is the News Editor for Prog magazine and has been a contributor to the magazine since its launch in 2009. A music journalist for over 20 years, Grant writes regularly for titles including Classic Rock and Total Guitar, and his CV also includes stints as a radio producer/presenter and podcast host. His first book, Big Big Train - Between The Lines, is out now through Kingmaker Publishing.