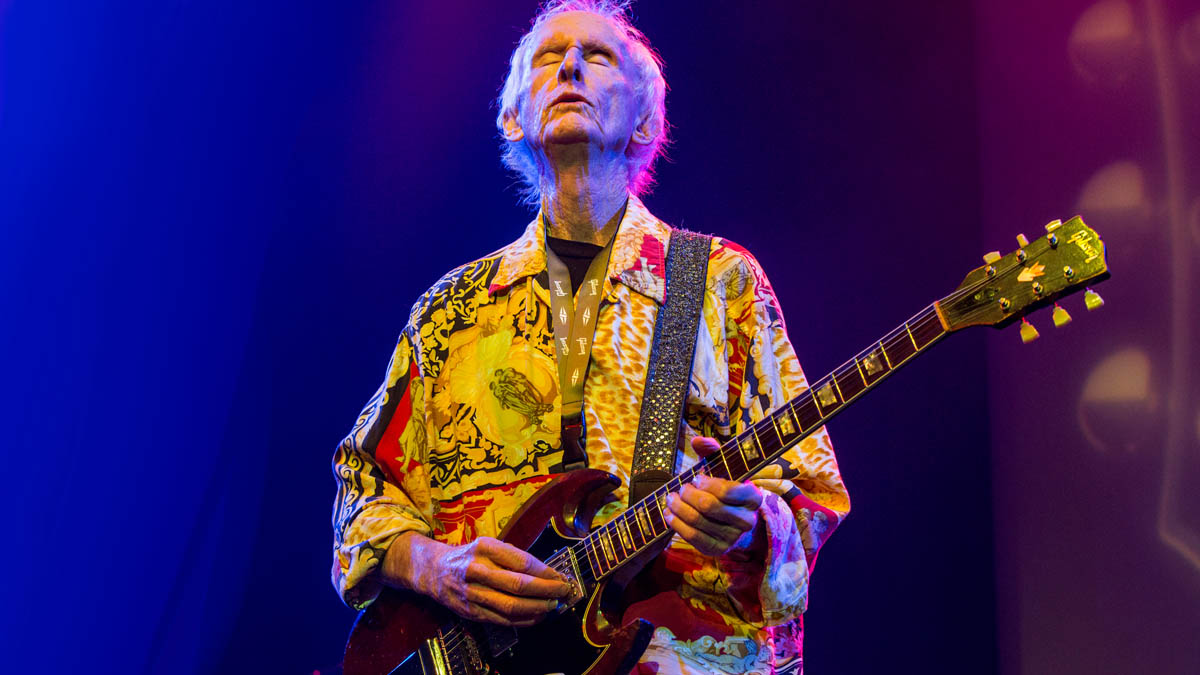

Robby Krieger: "I always like to be really near the amp, to keep the dynamics going between guitar and amp"

With 'The Ritual Begins at Sundown,' the Doors guitarist's jazz muse runs free

“I didn't play Doors music for a long time after Ray Manzarek passed away,” sighs Robby Krieger. Instead, when Manzarek, his longtime friend and keyboard foil in the Doors – the group in which both musicians became rock legends in 1960s alongside drummer John Densmore and late singer Jim Morrison – passed away in 2013 from cancer, Krieger took a break from performing Doors material for the next half-decade and threw himself into the jazzier side of his musical personality.

He deepened his alliance with Frank Zappa bassist/arranger Arthur Barrow – not to mention Zappa alumni like keyboardist Tommy Mars and trumpeter Sal Marquez.

The result, honed over several years of live gigs and studio dates, is the bebop- and fusion-infused instrumental LP The Ritual Begins at Sundown, which boasts an original Krieger abstract painting on the cover and the kind of altered-scale-tinged melodic heads one might associate with players like John Scofield, Kurt Rosenwinkel or even Zappa, whom Krieger pays homage to on a blazing cover of Chunga’s Revenge.

It features wicked horn/guitar harmonies and a wild free-form solo that recalls Zappa’s SG through-a-parked-wah tone and the almost-dissonant flurries and fuzz arcs of Krieger’s solo on the Doors’ When the Music’s Over.

“It was very collaborative on Ritual,” Krieger says. “Much more so than my earlier solo albums, like [1989’s] No Habla or [2010’s] Singularity. I might start something off, and Arthur would come in with some ideas; Tommy would add melodies, too.”

Horns and guitars work off each other in funky syncopation on The Hitch or play in bebop-approved unison on the long mixolydian-flavored lines of Dr. Noir.

When his turn comes to blow, I ask, is Robby thinking in terms of particular modes, chord tones, scales or arpeggios?

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“I tend not to think about that stuff,” he explains. “For me, it just gets mechanical when I do that. I just like to see where the music takes me. A lot of the solos on Ritual were overdubbed, and I have a certain way of doing that, which is playing into the solo as far as I can go, deciding if I want to keep what I’ve got so far, then punching in at that point.

“I keep that process going until I finish it. It’s not exactly comping – I don’t really care for the results when you comp together, like, five or six different takes of a solo and pick the best parts. That doesn’t really work for me.”

Jim had the most amazing vocal range I’ve ever heard. And not only the range, but the power

Comping of a kind certainly worked for Krieger – though in an unexpected way – when he recorded the landmark guitar solo on 1967’s When the Music’s Over, from Strange Days, at L.A.’s Sunset Sound, tracking the guitar solo several times, standing directly in front of his Twin Reverb and early Gibson Maestro Fuzz-Tone pedal.

“I always like to be really near the amp, to keep the dynamics going between guitar and amp,” he says. “Engineers are always trying to stick the cabinets in an iso [isolation] booth, but that never works for my sound.”

When the sound “still wasn’t happening,” Krieger says, he asked producer Paul Rothchild if there was “some way to make it sound almost like a violin” – total sustain.

“Paul opens his briefcase,” Krieger recalls, “and he pulls out this little diode, or some fucking thing, and he says, ‘Wait 10 minutes.’ He solders the thing into one of the channels on the board, and that was it. That’s what created that sound. I wish I could have bottled that. I’ve been trying to reproduce that sound ever since!”

That wasn’t the only bit of magic-in-a-bottle on Krieger’s solo.

“So, after I cut maybe four or five versions of the solo, when we were listening back, Bruce Botnick, the engineer, had left two of the solos up [on the mixing board] by accident. Bruce goes, “Oh, sorry, I had two of them going there. Wait a minute…” And we said, “No! Leave that right alone! That might work!” And it did; it worked fucking perfectly.”

As with the Doors, Krieger’s playing still retains flashes of his early flamenco heroes like Sabicas, rock, jazz and blues giants like Chuck Berry, Wes Montgomery and Albert King, folkies from Dave Van Ronk to Bob Dylan, and world-music avatars like Ravi Shankar.

On last year’s 50th Anniversary Deluxe Edition of the Doors’ 1969 album The Soft Parade, Krieger added terrific new solos to stripped-down alternate mixes of Touch Me, Wishful Sinful and Runnin’ Blue, replacing those songs’ heavy orchestrations with his lithe licks and a grittier “Doors only” sound.

Krieger remains a huge admirer of his late Doors bandmates’ musicianship, pointing to Manzarek’s lyrical piano playing on the Krieger original Yes, the River Knows, [from 1968’s Waiting for the Sun] which is covered on Ritual with Robby playing the vocal lines on slide.

“That’s one of the best parts Ray ever played,” he beams. “People usually think about Ray on Light My Fire or Riders on the Storm, but I wish they’d recognize Ray for that one.”

After so many years of myth-making and misunderstanding about Jim Morrison, what does Krieger wish people would remember best about Jim from a musical point of view?

“Jim had the most amazing vocal range I’ve ever heard,” Krieger says. “And not only the range, but the power – and he was never out of tune. Jim was a total natural. It’s amazing how many people think they can sing like Jim but can’t really do it.

“Jim had this incredible power in his voice, and I don’t know where it came from, because he definitely didn’t have it at first, but it developed really fast. At our first gigs, Jim sounded like a kid, which, I suppose, he was. But, man, he turned into the most amazing singer.”

The Gear Parade, with Robby’s Tech: Wild Child’s Forrest Penner

“Forrest knows my parts better than I do!“ laughs Robby Krieger, talking about his longtime guitar tech, Forrest Penner, who’s also been the axman for L.A.’s premier Doors tribute act, Wild Child, since the mid Eighties.

“One of the first times we played together on stage,” recalls Penner, “Robby invited me up to play the double solo on When the Music’s Over with him, and after it was done, he turned to me and said, ‘Now, that’s how it’s supposed to sound!”

Penner, who’s also teched for Jefferson Starship, Doyle Bramhall and others, was so well-versed in Krieger’s vocabulary, that he even subbed for Robby on some huge Manzarek/Krieger Band shows in Mexico and South America when the Doors guitarist fell ill in 2011.

“I was a little stressed, because after each of the first few songs, the audience was cheering, and chanting, “Rob-BY, Rob-BY,’ so Ray had to explain who I was, and why Robby himself wasn’t there. But the audience was great about it.”

Krieger’s main ax, says Penner, is a brownish-red 1967 Gibson SG, which Krieger bought used about 25 years ago. (His original SG Special with P-90s from the first few Doors albums was stolen many years back.)

“It plays magnificently,” says Penner, with a thin neck profile, and a Gibson Maestro Lyre Vibrola tailpiece. Krieger also plays a circa-2000 Gibson SG RK-1 Robby Krieger Signature model set up for slide in either open-G or open-D. Penner strings both guitars with Ernie Ball 2221 Regular Slinky Nickel Wound strings, .010-.046.

Live, Krieger typically plays through a Fender Hot Rod DeVille 4x10 combo amp, though he was best known for using Magnatone, Fender Twin Reverb, and Acoustic 260 amps in the Sixties.

Robby’s parts are interesting, because at first they might seem easy to play, but they’re very hard to play accurately. Using your fingers is the only way to really get the Robby sound

Forrest Penner

When Krieger, who’d been using a BOSS ME-10 multi-effector, expressed an interest in Penner’s more boutique-leaning board with Wild Child, Penner built Robby a similar custom board, using a Pedal Train Classic chassis and a Tru-Tone 1-Spot Pro power supply.

From the guitar, using a Cordial Encore braided High Copper Series cable, Krieger’s SG hits a Boss TU-2 tuner, Dunlop Mini Cry Baby Wah, Boss CE-B Bass Chorus (for Love Her Madly), Boss TR-2 Tremolo (for Riders on the Storm, Strange Days and others), a vintage Ibanez TS-808 Tube Screamer with light gain, a reissue TS-808 Tube Screamer with heavy gain, an Xotic Effects SP Compressor for clean boost, a TC Electronic Flashback Delay, and a BOSS DD-7 Digital Delay, with an expression pedal to modify the wet/dry mix. An Ernie Ball VP Jr Volume Pedal rounds out the board.

“Robby’s parts are interesting,” Penner says, “because at first they might seem easy to play, but they’re very hard to play accurately. A lot of people wouldn’t guess, for instance, that Robby played the riff to Roadhouse Blues with his fingers, not a pick.

“He also plays with his fingers on Love Me Two Times, 20th Century Fox and many more. For those parts, I use a hybrid pick/fingers technique myself – but using your fingers is the only way to really get the Robby sound.”