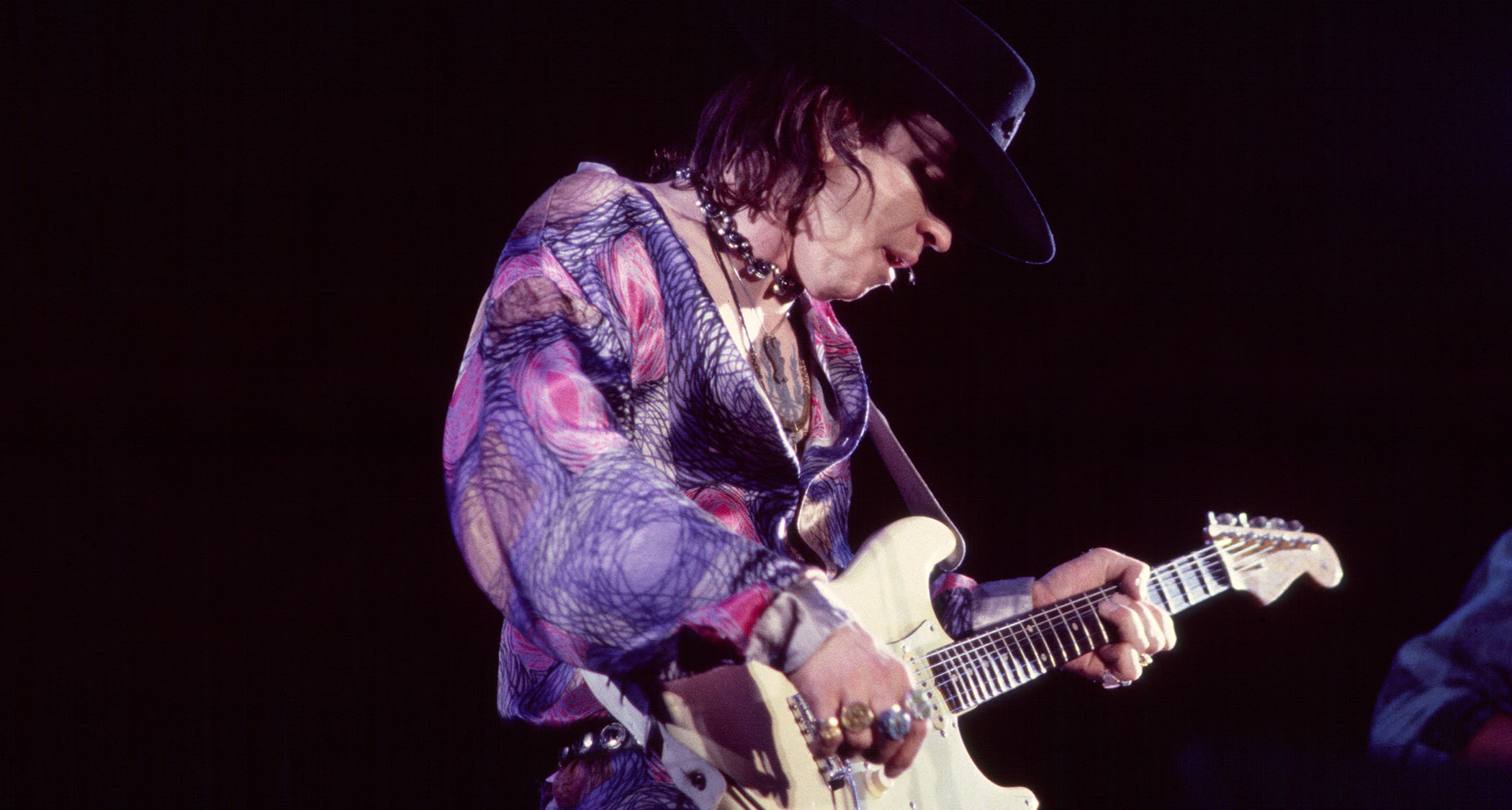

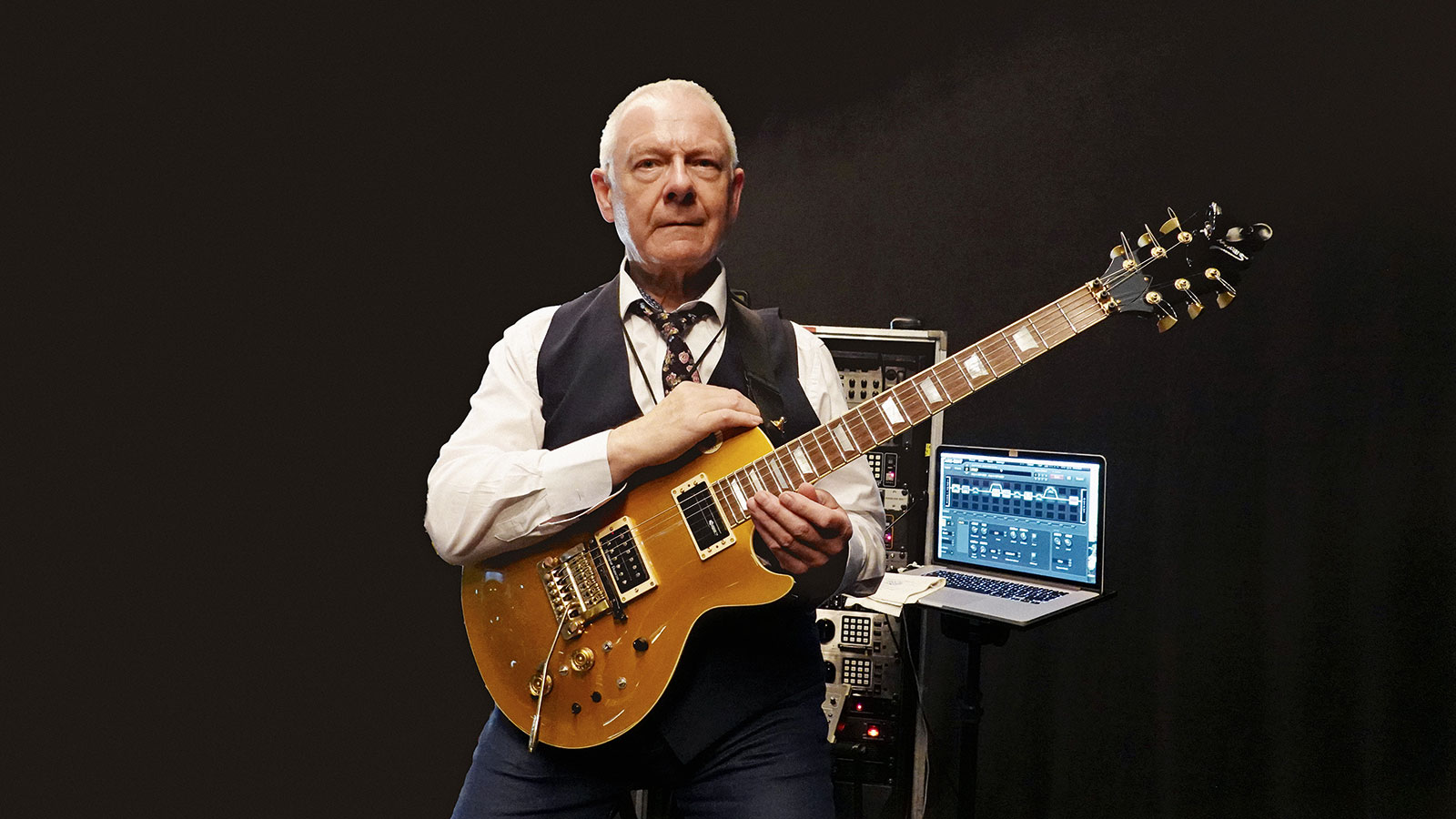

Robert Fripp in-depth: his quest to combine Hendrix and Bartók, what made King Crimson “problematic” and why he has “no interest in gear at all”

In this exclusive interview, we sit down with the brilliant and divisive progressive guitar icon to discuss the art of Guitar Craft and the highs and lows of King Crimson – and get an intimate look at his guitar collection

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

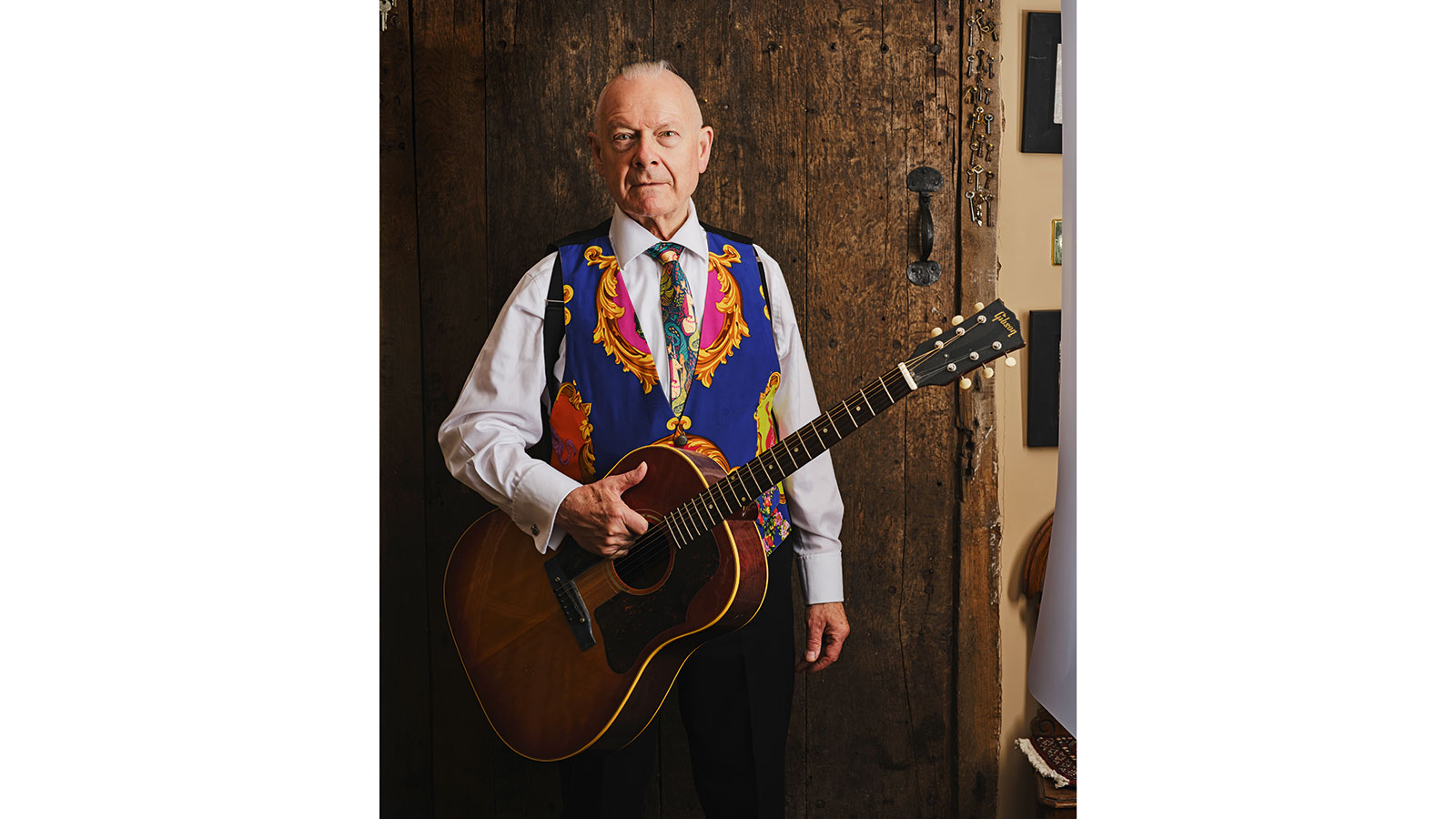

With a 32-disc boxset of his solo work during the late 1970s already released into the wild and a guitar book coming out in early autumn, Robert sits down with us at Fripp HQ in the middle England countryside to talk all things King Crimson, as we take an exclusive look at the instruments that have given voice to some of prog-rock’s finest moments...

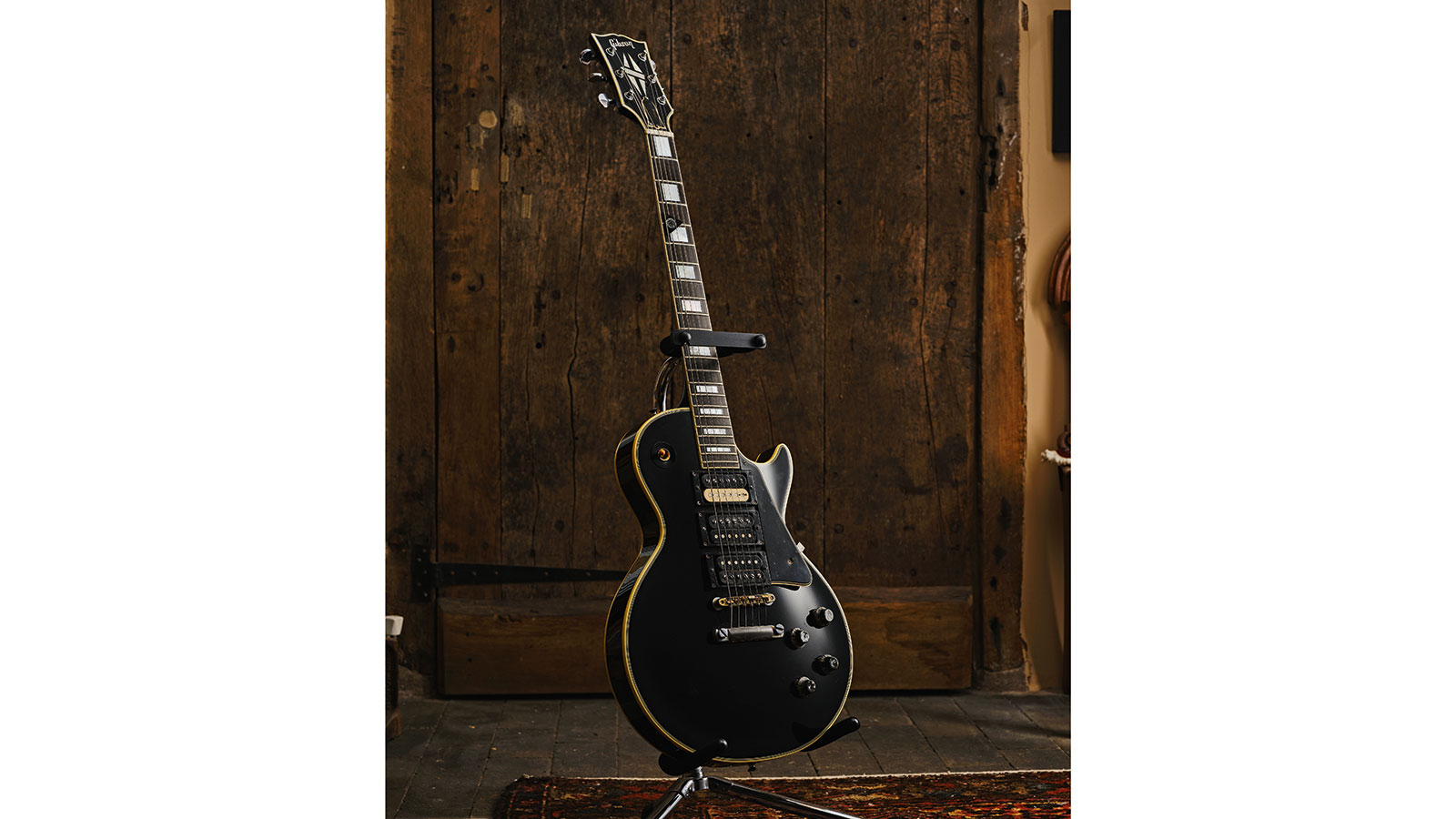

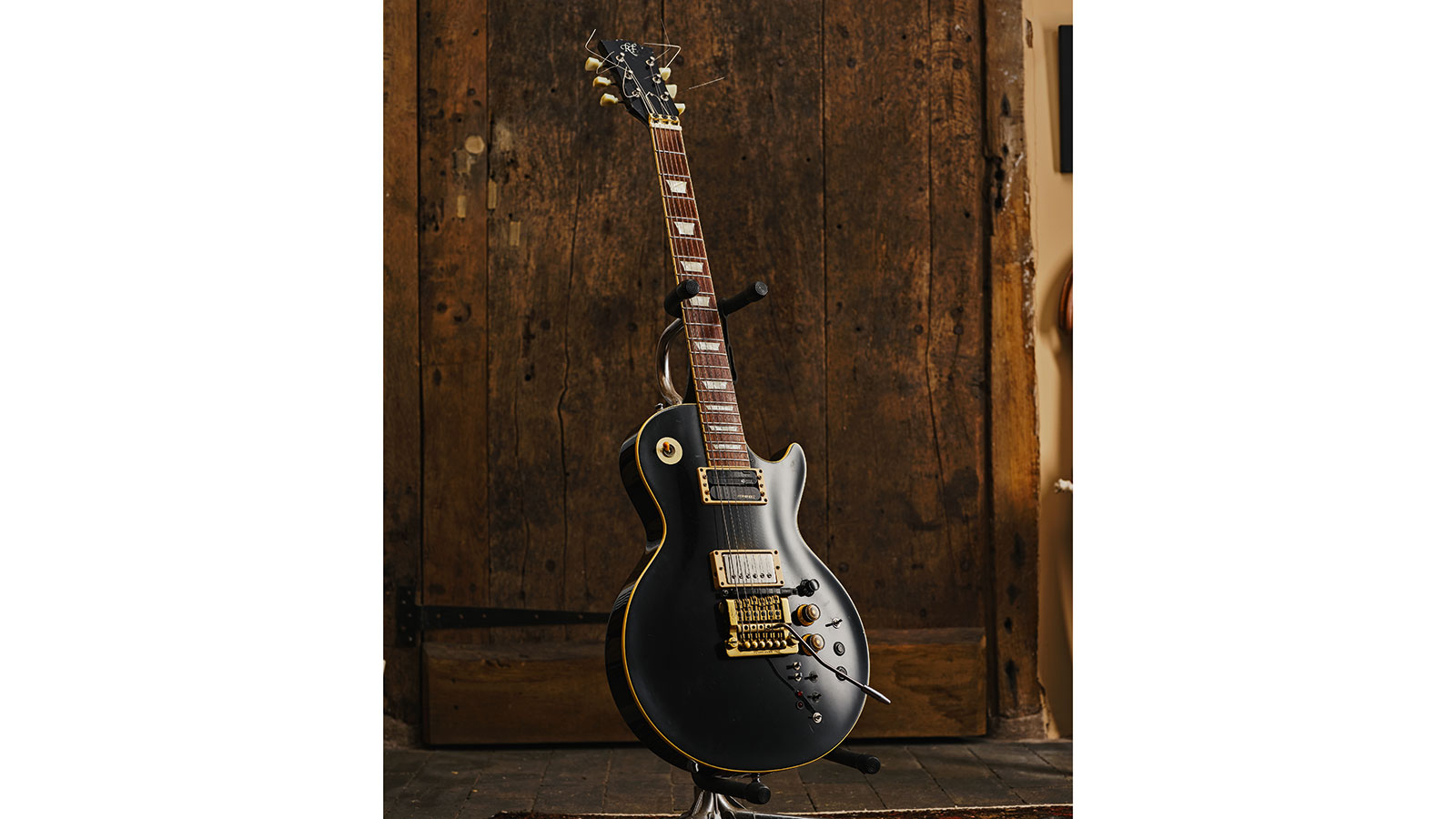

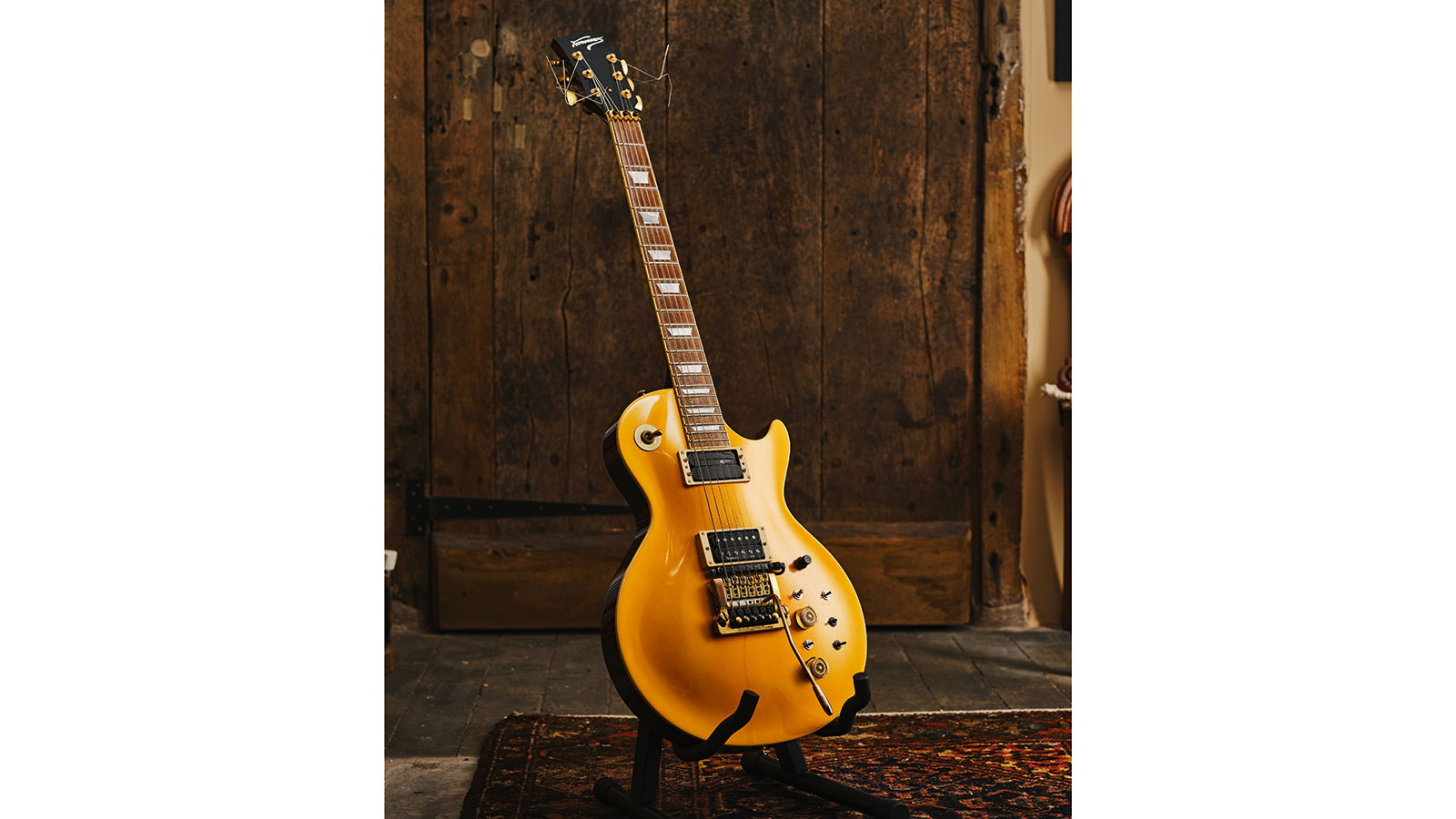

Interviews with ‘That Awful Man’, as Robert Fripp refers to himself these days, are rare, and until now he hasn’t allowed his collection of guitars to be photographed, including the ’59 Les Paul Custom that was used on so many classic Crimson albums.

“I don’t collect guitars,” he tells us as we settle down to talk, “they are merely tools that I use in my work.” However, we note that the famous ’59 appears to be in almost pristine condition – in fact, it’s still shiny even after years on the road. “One careful owner,” he quips with a wry grin.

Anyone who wants to assess Fripp’s skills as a guitarist need only check out Fracture from the King Crimson album Starless And Bible Black. The Moto Perpetuo from that piece is a legendary example of his crosspicking finesse.

His guitar journey began with lessons that found him playing some challenging classical pieces with a plectrum, instead of the more conventional fingerstyle. This influence reached into the Crimson repertoire and is apparent in 1970’s Peace – A Theme from In The Wake Of Poseidon.

“Yes, Carcassi Etude No 7, the middle section,” he tells us. “You probably wouldn’t be able to see the connection, but Peace – A Theme wouldn’t have quite ended up that way unless I practiced the Carcassi Etudes for fingerstyle, but with a pick because crosspicking was my speciality.”

Now that Crimson has entered another hiatus, the rendition of Starless in Japan last December being regarded by all as the last we’ll hear from the band, it’s time to catch up with Crimson’s only permanent member. And we start our conversation at the very beginning...

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

How did you become interested in music – and specifically the guitar – in the first place?

“My trajectory was at age 11 my sister and I bought two records, Rock With The Caveman by Tommy Steele and Don’t Be Cruel by Elvis Presley. The guitarist on Tommy Steele I learnt later was Bert Weedon, on Elvis, Scotty Moore. There weren’t any English rock musicians, they were all jazzers. Old men, basically. Old men who would come in and do the young character sessions.

I saw The Outlaws at a show in Poole when I was 17 with Ritchie Blackmore, he was then 18. He was phenomenal

“Mel Collins’ [Crimson sax player] father would be doing the ripping tenor solos on [BBC music programme] Six-Five Special with Tubby Hayes and Ronnie Scott sitting next to him. They would be making derogatory comments on these young rock artists who really weren’t in the same musical ballpark as they were.

“In America it was entirely different. There was nothing demeaning about playing rock music and moving out of blues. Scotty Moore, Chuck Berry, the sheer power of Jerry Lee Lewis... That was me around 11 to 12.

“At 13 trad jazz came along. I would go down to the Winter Gardens in Bournemouth and see all the characters: Chris Barber, Acker Bilk, Monty Sunshine and just about everyone else that was working at the time. Memphis Slim I saw there, too – I think he was supporting Chris Barber. Wow, wow. At 15, hearing Mingus, Extrapolation. Max Roach, Town Hall New York City.

“Then, at 17, the more challenging aspects of what we call classic music. It segued into The Beatles and 1960s English rock instrumentals. I saw The Outlaws at a show in Poole when I was 17 with Ritchie Blackmore, he was then 18. He was phenomenal. He had all the moves. He had the music, he had the playing, it was astonishing.

“The Bournemouth scene was very hot. Working in the first League Of Gentlemen we would do lots of specialty vocals: Four Seasons, Beatles. We would also do the instrumental specialities, Entry Of The Gladiators, which I didn’t realize until I met him years later was Mick Jones of Foreigner. Then I went off to college to take A-levels to go onto university and take a degree in estate management.

“My musical interest went slightly to the side, and I went to the Majestic Dance Orchestra to pay my way through college. When that came to an end, there was Hendrix, Sgt Pepper and things shot off in a different direction, to the extent I could no longer continue. Going on to London where I’d been accepted for a place for three years to take a degree in estate management at the College of Estate Management in South Kensington, I had my digs booked in Acton; how awful that was. I said to my father, ‘I can’t continue,’ and I turned professional on my 21st birthday.”

What was the first guitar you had when you began playing?

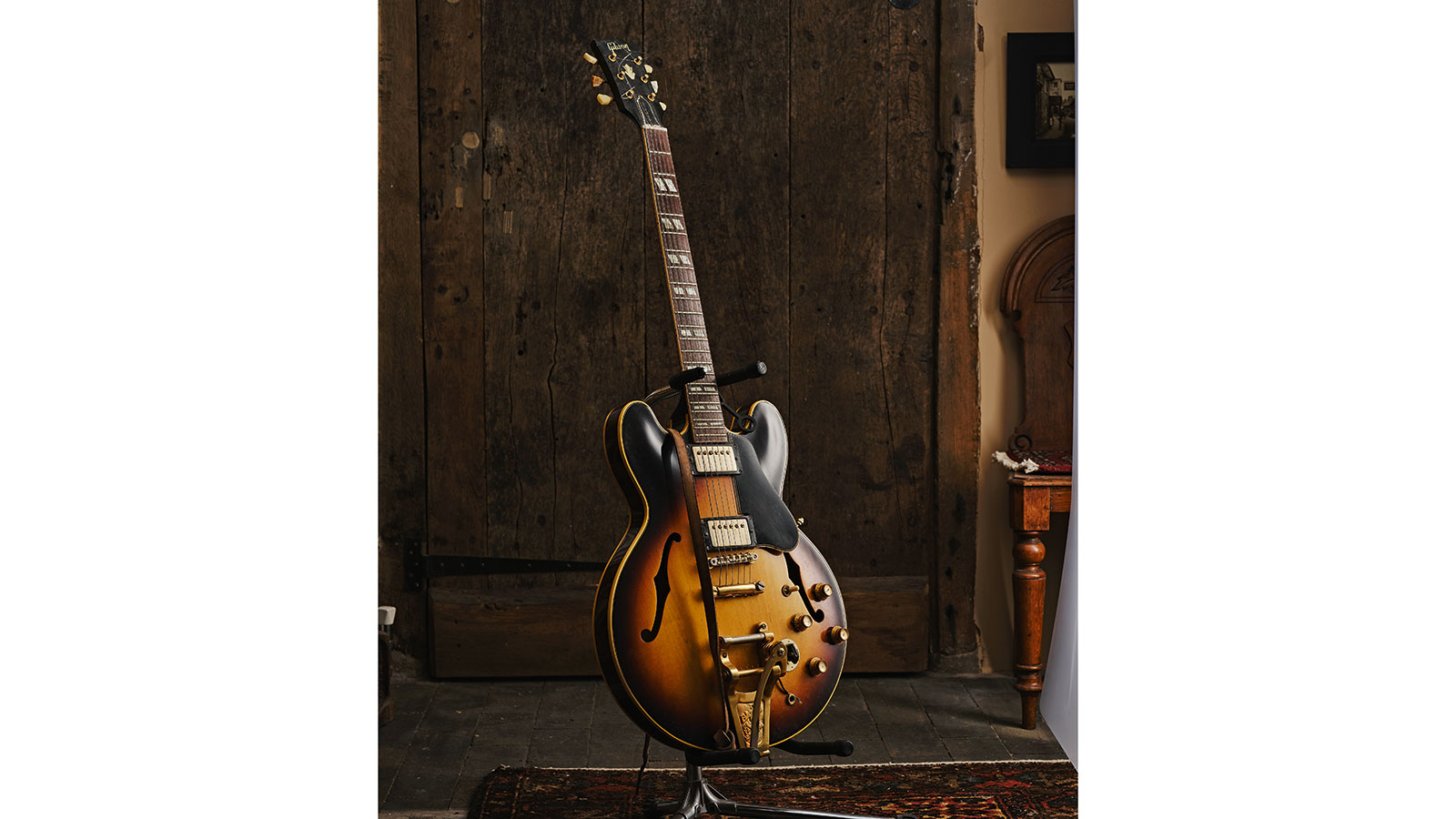

My first good guitar was my Gibson ES-345 Stereo, which I used until 1968 when I got my first Les Paul

“It was an Egmond Freres, an appalling instrument. The action at the 7th fret, you needed pliers to depress it. It was appalling. It required me to develop such strong muscles that I remember in 1971 practicing to put less pressure into my left hand. I moved onto a cheap Rosetti guitar, which was not good. Then a Höfner; I believe it was a President, it was the cutaway version. It wasn’t great, but at least it was an instrument.

“My first good guitar was my Gibson ES-345 Stereo, which I bought from Eddie Moors music shop in Boscombe where on a Saturday afternoon I would give guitar lessons. Young characters would come in and say, ‘I’m interested in buying a guitar.’ They’d say, ‘We have an in-store guitar teacher who can give you lessons on Saturday afternoon.’ I’d go around the corner to something like a village hall in Boscombe and give guitar lessons.

“Then in the evening I’d go on to Chewton Glen Hotel, this was when I was 17, and play in the Douglas Ward Trio. This was my first good guitar, and it was expensive, something like £350. That was the guitar with The League Of Gentlemen. That took me to London with Giles, Giles And Fripp, that guitar, which I used until 1968 when I got my first Les Paul. I only used the 345 again with Crimson on In The Wake Of Poseidon on Cat Food, and Bolero [from Lizard].”

1959 Gibson Les Paul Custom

Was there an influence on you musically from listening to classical music?

“I began listening to the Bartók String Quartet and Stravinsky’s Rite Of Spring. The turning point in my musical, and I suppose personal, life was something like ‘music is one’. I didn’t hear separate categories, I heard music but as if it was one musician speaking in a variety of dialects. The crashing chords of Rite Of Spring or Bartók, where is that coming from? The opening bars of Purple Haze or Day In The Life, I Am The Walrus, it all had this incredible power as it reached over and pulled me towards it.”

You’re well known for your crosspicking ability on pieces such as Fracture. How did this skill begin to develop?

“It’s what in Guitar Craft is called ‘a point of seeing’. It’s not the process of rational deduction of working out; you simply see something. I remember specifically the moment. I was at home in the first floor rear room where my sister and myself would do homework. I was practicing Study In 3/4 by Dick Sadleir.

“My guitar teacher, Don Strike, gave me a very good technical foundation. In terms of current music, it was a little old-fashioned. It was kind of corny for a young character who enjoyed Scotty Moore. Instead of doing bom-bish-bish bom-bish-bish, I began crosspicking. The same shapes, the same notes but crosspicking it.

“Seeing that that was so obviously the way to go I continued to develop that as a speciality, including [Francisco] Tárrega’s Recuerdos de la Alhambra, which was a very challenging piece for the pick.”

There’s not a great deal of blues influence in your playing...

The question eventually became formulated for me as, ‘What would Hendrix sound like playing the Bartók String Quartets?

“Why didn’t I become a blues guitarist? Probably because I wasn’t a very good blues guitarist. The thing is, a lot of young players and some established players have said to me, ‘I only wanted to be like Clapton.’ They didn’t say it, but you knew it. That wasn’t my aim. Stunning player, but... The question eventually became formulated for me as, ‘What would Hendrix sound like playing the Bartók String Quartets?’

“In 1969 the major musical influences in Crimson were Ian McDonald and Michael Giles. I recognized they had a connection with music, which at the time I didn’t have, but I could recognize in others. I’d known this probably since I was 17 or 18 working alongside and going to see the other young players in Bournemouth, stunning young players.”

How did McDonald’s and Giles’ influence connect with you in Crimson’s early days?

“In the studio recording In The Court Of The Crimson King they would make a comment, [and] I would adjust my response to sit in accord with theirs. Then when they left it was heartbreaking for me, because although Giles wasn’t a writer his contributions to the arrangements and direction were stunning.

“My primary role for In the Court... in Crimson in 1969, as I saw it, was to come up with guitar parts that supported the writing. Although you could say that McDonald and [Peter] Sinfield were the main writers, you can’t exclude Giles from that. You can’t really exclude anyone from that, it was five people.

“Moonchild on that album, the music was 99 per cent Robert [Fripp, himself] with one suggestion from Ian McDonald to move a G to a G#, which we incorporated. This was Ian, he had a gift for the simple melodic phrase.

“That’s what we went with. For the writing credit, which properly should have been Fripp/Sinfield, I decided to have all the names of the members because I felt that actually everyone was involved equally. How can you exclude anyone at that point? For me, Crimson has always been a co-operative, which it certainly was in 1969.”

This led to some turbulence within the band, didn’t it?

“My personal difficulties with any Crimson musician since have been if they favor themselves or see themselves as somehow coming ahead of the other players or the music. To put that positively within Crimson, the music comes first: principle one. Principle two: the band comes first. The interests of the band come ahead of the interests of the other players. Three: we share the money. Why do there seem to be personal difficulties? Look at those three principles and really that’s the clue to anything that follows.

There was never a conflict of interests with Robert [me]. If I said, ‘Look, lads. I think we should do this.’ It was because I thought we should do this

“If the music does come first, then all the names are there at the top. We shared the record royalties; we shared the publishing royalties. There is a legitimate concern that if you have one person who writes all the music, shouldn’t they get a disproportionate part of the publishing? The answer is yes, they should. This was a legitimate concern for Adrian Belew.

“From 1994 onwards, we would look at essentially who had made the greatest contribution to writing this piece. Between 1970 and 1974 when Robert was the primary writer, even if Bill Bruford didn’t play a note he would receive an equal share of the publishing income. Why? Firstly, because it exemplified the view that where there is an equal commitment there is an equitable distribution.

“Secondly, if Robert made a value judgement or recommendation that we go this way, there was never any question that my recommendation for either a musical or business direction favored me. There was never a conflict of interests with Robert. If I said, ‘Look, lads. I think we should do this.’ It was because I thought we should do this. Why? Primarily for the music, then primarily the interest of the band and so on.”

Gibson ES-345

The recent release of the Exposures boxset features Steven Wilson remixes of your solo material. As with the Crimson remixes Steven has done, they’re remarkably faithful to the originals.

“When I go in to mix something, I don’t go in with a historic overview to mind. Steven’s aim was very faithfully to reproduce the original but with modern technology. There had been the odd discussions. For example, with Lizard there were one or two things we didn’t quite put in and so on. My view on occasion has been we actually didn’t get it right the first time, so now is an opportunity. Then you say, ‘What’s right and what’s wrong?’ If it has been adopted and accepted by decades of listeners, then maybe that’s what it is. Steven aims to get it exactly as. Me, I’d be very happy to go a different way.

“In terms of Exposure I went down and worked with Steven, I was very up for complete reimagining. Steven: ‘No, this is a classic.’ His brief, this is Steven, is to present this as the original. How can I put it? That desk [pointing to an antique writing desk in the room in which we are sitting] is an 1830s desk. It’s a classic of its kind. If I were designing a desk for today to use with modern things, such as having computers on the side, it wouldn’t be designed like that. However, for me that is the classic and I’m not going to redesign it. That’s Steven’s point of view: this is the classic. The only innovation we had on Exposure was with [Dolby] Atmos mixing, which isn’t, I suppose, entirely legitimate.”

Revisiting Exposure, it is possible to see a stylistic link between the albums Red from the mid-70s and Discipline from the early 80s, with the two guitars playing offset then synchronous parts. Was this an idea forming in your mind during Crimson’s hiatus in the late 70s?

I met Adrian [Belew] at The Bottom Line in New York. Bowie was there with Adrian. We said hello and Adrian said, ‘Let’s get together for tea tomorrow,’ so we did

“Was it Steve Reich? Was it Philip Glass? Was it Robert Fripp? Was it in the air? Was it world music? Anyway, all of this, my thinking, my academic interests and approach to music were in place in 1980, 1981, with the coming together of that form of King Crimson. I met Adrian [Belew] personally at The Bottom Line in New York when I went down to see Steve Reich. Bowie was there with Adrian. We went over and said hello and Adrian said, ‘Let’s get together for tea tomorrow,’ so we did. That’s how our personal connection began.”

People might not be aware that you actually write these pieces out on manuscript paper.

“Yes, I do. I don’t give the other players charts. I don’t like the word ‘bandleader’ because I’ve never viewed myself as a bandleader. That’s another endless wittering on. You have [Charles] Mingus. I understand that Mingus didn’t give the other characters in the band charts. Why? Because it goes in through your eyes. You present the music you have and you say, ‘If I’m playing this, what are you playing?’ One of Bill’s good quotes from the time was, ‘It was as if Robert expected us to know what to play.’ Of course. If I have to tell you what to play, why are we working together?

“What I would aim to do is construct situations or conditions within which the talent of each of these players is given an opportunity to develop. To the extent that when Robert composed for Crimson it was writing specifically for these people in this band to play. Not a generic piece that anyone could play, it was specifically for these people.

“There were two occasions when I presented Larks’ [Tongues in Aspic, Part] Two to that formation of Crimson. We had short rehearsals in Covent Garden and then we went to Richmond Athletic Club. I presented the defining Larks’ rhythm and chords at Covent Garden and it wasn’t heard, it went nowhere. Then I played it at Richmond Athletic Club and Bill and John [Wetton] leapt straight in. They had it; clicked, it worked. Most really good rock drummers in London at the time wouldn’t have heard it because it wasn’t written for them.

If you would like a band to break up, have writing rehearsals. What you do when you hit that problem is you get on the road

“With Crimson it was an open form of engagement, which has always been complex, always problematic and always very demanding. If you would like a band to break up, have writing rehearsals. What you do when you hit that problem is you get on the road. Then you introduce an audience into the situation, music comes to life and you’ll keep going. Not that Robert is a bandleader, but in terms of practical strategies for keeping the band together and working, you move from writing rehearsals as quickly as possible into live performance.”

Can we talk a little about gear?

“You know I have no interest in that. I have no interest in gear at all. For example, whatever fuzzbox, whatever guitar, whatever amp I’m using I’ll get my sound. Here’s an example of this. I went to see Herbie Hancock and Chick Corea at Carnegie Hall: wow, breathtaking. Chick Corea is stage right, Herbie Hancock on the left. They changed places and played and their sounds went with them. I still don’t understand that. How can that be? It cannot be that the sound of a piano changes. The sound of a piano is the sound of a piano, surely?

“With Crimson I use Axe-Fx, which is very good. For basic work that I can carry myself without a team of engineers I use a Helix. Why? Because Jakko [Jakszyk] uses a Helix and if you’re working in a band with another character you aim for compatibility. The other thing is, he can tell me how to work it.”

The rig you use for soundscaping hasn’t changed too dramatically over the years, has it?

“It changed. I’m trying to think when it changed from the ‘Solar Voyager’ to the ‘Sirius Probe’. It changed when I stopped using the [TC Electronic] TC2290, which I used to use for sampling. It developed high-level digital frizz. I started using the Eventide 8000s, which are astonishing things. You have 90-second samples that will repeat. You can leave them 24 hours, come back, no decay, no degeneration whatsoever. For sampling, that’s astonishing. There is something irreplaceable in those early versions of the Eventides. I’ve no idea what the algorithms are, but wow. They shape the sound.

There are ratios within the time delays generally in terms of six or seven seconds. Lots of experience – including being booed constantly – has suggested to me this has resonance

“In terms of the 8000s where I have bona fide quadraphonic sound, what I do is I work to ratios in delay. If you have four outputs, if a short loop is needed, one stereo pair will have 12 seconds on one side and 18 seconds on the other. You have a 3:2 ratio. On the next one I tend to have an offset of maybe 20.5 to 21 seconds. It’s just essentially the same delay, which over a period of maybe half an hour will change.

“If I’m going for longform soundscapes it might be something like 42:49 or 42:63. On the other stereo pair to complete the quadraphonic might be 21:35 or 63:72. In other words, there are ratios within the time delays generally in terms of six or seven seconds, which lots of experience – including being booed constantly – has suggested to me this has resonance.

“I’ll then go in and I have my defining programs within the Eventide 3000s, which sends it shooting off in different directions. In terms of soundscape performances, I bypass all of that and through an Eventide Eclipse I have a solo sound. It gives me my solo voice. In the quiet moments the solo voice will come up with all of this, all in real-time.

“I have had various suggestions, ‘Bob, why don’t you use Ableton Live?’ The answer is, when I’m doing a live performance soundscape with the rig I have, the Sirius Probe, all of the parameters I can change in real-time by hand as I am playing. I don’t have to go to a computer and fiddle about. I don’t have to look up here and see what’s going on, I can do it all with one hand.”

Tokai LP-type

Are you still using the Roland GR-1?

“It’s set up in my full Crimson rig. I haven’t been using it recently, but I have used it certainly in 2015, probably using it for the first half of seven-, eight-piece Crimson. Why? Because it does two or three things that nothing else does. The same as the 3000s. The GR-1 has a fretless bass sound, that is breathtaking, which I would use to have fun with Tony Levin. Tony would be doing some upright slides, I might slip in some fretless. Tony would look up wondering where the bass sound was coming from.

“It’s also stunning in terms of low-end for soundscapes. It also has bell sounds, which in combination with an Eventide 3000 programme called ‘In Six’ makes astonishing sounds. It also has a piano sound, which I haven’t really used since 2003, but which was astonishing. I used it a lot in all the ProjeKcts.”

Technology has come a long way since your early Frippertronics work.

“Yes, that’s right. I’ve had these posts, ‘Bring back the ReVox. Where is Frippertronics?’ It’s just not feasible. Why not? If you go back to when I used that technology you’d have to fly it. What would happen if there was a bounce? Here’s another one: you have it set up on the table, what would happen if someone walked by and bumped the table? The answer is, there would be a fluttering on the tape. You’d then have to shape the entire Frippertronics piece around the flutter. If, as in Madrid in May 1979, what happens if the ReVox the record company has brought in begins to catch fire? What do you do? These are practical examples. It’s not feasible.”

Would it be true to say that The Guitar Circle book you have coming out in September isn’t what you might call a conventional guitar tutor?

How we respond to someone’s [musical] intention before there’s any movement at all is a subtle thing. It falls under the heading of ‘cosmic horse shit’

“Correct. It’s the attitude. It’s less what you do, it’s more how you do and why you do. We’ve now had guitar courses since March 1985 and the book is essentially a report on the history of Guitar Craft and the Guitar Circle to date. If you’re looking for a book of guitar exercises, this is not the way to go.

“People who have a background in martial arts feel an immediate affinity with Guitar Craft in the Guitar Circle. One character said to a pal of mine it’s like martial arts with a guitar. I’ve a little tai chi, some muay Thai. Here, your response is governed by the intentionality of the person with whom you’re sparring. If you wait for them to make a move you’re on the floor.

“What you respond to is their intention. How we respond to someone’s intention before there’s any movement at all is a subtle thing. How to explain that? That falls under the heading of ‘cosmic horse shit’. The point is, it can very easily be experienced.

“Guitar Craft was basically developing a personal discipline with a guitar. The Guitar Circle is developing a personal discipline within others. We’re learning to work with others and with ourself. In a sense it’s a maturing and a development within a social context.

“One of the difficulties I’ve had doing interviews over a period of 53 years with guitar magazines is that just about everything that is real with me in terms of how I experience and engage with music and other musicians is subtle. If I’m explaining it in bold terms, it falls under the heading of cosmic horse shit.

“One of the important principles in this is ‘accept nothing that someone is telling you, presenting you, judge by your own experience’. When someone comes into a Guitar Circle, don’t take Robert’s view of what might be happening for yourself, what is your experience?”

Fernandes Gold Custom

- Robert Fripp’s 32-disc boxset, Exposures, is out now, via DGM/Panegyric. The Guitar Circle book will be released on 1 September via Panegyric Publishing in association with Discipline Global Mobile.

With over 30 years’ experience writing for guitar magazines, including at one time occupying the role of editor for Guitarist and Guitar Techniques, David is also the best-selling author of a number of guitar books for Sanctuary Publishing, Music Sales, Mel Bay and Hal Leonard. As a player he has performed with blues sax legend Dick Heckstall-Smith, played rock ’n’ roll in Marty Wilde’s band, duetted with Martin Taylor and taken part in charity gigs backing Gary Moore, Bernie Marsden and Robbie McIntosh, among others. An avid composer of acoustic guitar instrumentals, he has released two acclaimed albums, Nocturnal and Arboretum.