All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

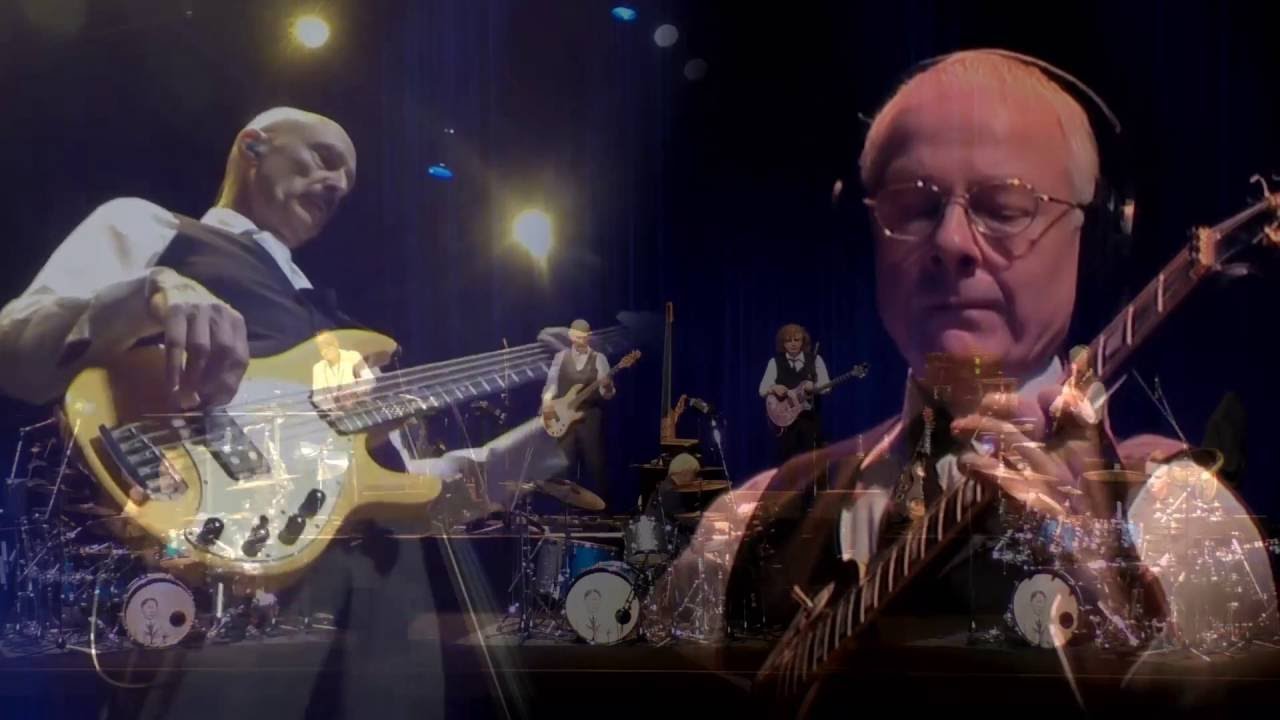

Robert Fripp is widely hailed as the king of progressive rock guitar – but he squirms visibly under that crown. In 2014, asked by Classic Rock if he’s always taken issue with King Crimson’s “prog” label, he made his feelings blatantly clear: “Yes, it’s a prison,” he said. “If you walk on stage and you’re playing music, fine. But if you’re walking on stage and you’re playing progressive rock – death.”

In a way, that discomfort makes sense. As King Crimson’s key guiding force – and lone consistent member – since their debut LP, 1969’s In the Court of the Crimson King, Fripp has typically veered away from popular tropes and trends.

Across 13 studio albums (along with a smattering of EPs and live records), he’s evolved from the band’s early pseudo-symphonic style to infuse the avant-garde, classical, borderline jazz-fusion, free improvisation, heavy metal, New Wave, industrial and multi-drummer mayhem. No style has ever been off limits, and every Crimson era is an island unto itself.

You can attribute much of that range to Fripp’s vision as a bandleader: no other rock musician is more willing to call it quits, embark on an extended hiatus and start from scratch with a new lineup. (And few have recruited so well for a particular artistic aim; it’s hard to imagine King Crimson’s sleeker ’80s revamp without the two American recruits, singer-guitarist Adrian Belew and bassist Tony Levin.)

After all, Crimson have never been a guitar-first band – it’s almost always been about ensemble composition, using the unique tools of the musicians in his company.

“If you listen to King Crimson’s records, you realize the guitar playing has always been one of the smallest things that the band does,” Fripp told Guitar Player in 1974. “One of the reasons for that is I’ve always been more happy in developing the other musicians; developing them as players.”

Democratic function aside, a great deal of Crimson’s endurance does boil down to Fripp’s creativity and prowess on guitar. He started playing at 11, learning on a right-handed instrument, despite being left-handed – and in a way, that was a bit of foreshadowing.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

If you listen to King Crimson’s records, you realize the guitar playing has always been one of the smallest things that the band does

He’s always been keen to experiment, to approach the guitar from an unlikely vantage point: devising an overlapping playing system with Belew in the ’80s, utilizing unconventional harmonies and rhythms, creating the tape delay technique known as “Frippertronics,” inventing New Standard Tuning (C/G/D/A/E/G), which he teaches students at his Guitar Craft courses.

And Fripp’s non-Crimson resumé is equally versatile. As a guest player (and occasional producer), he’s worked with art-rock giants (Peter Gabriel, Talking Heads), bona-fide pop stars (Daryl Hall, Blondie), prog bands (Van Der Graaf Generator, Matching Mole) and folk acts (the Roches) – not to mention his slightly under-the-radar solo projects and innovative collaborations with Brian Eno.

It would be impossible to fully survey the breadth of Fripp’s style in one semi-concise list. But in a modest attempt to highlight the imagination and influence of his guitar playing, we’ve selected 20 essential, career-spanning moments – from Frippertronic soundscapes to metallic riffs, from arpeggiated acoustic reveries to feedback fireworks.

20. Sky – Robert Fripp, from 1996’s Radiophonics (1995 Soundscapes Volume 1 – Live in Argentina)

It’s fair to say Fripp diehards are an open-minded bunch, but many faithful found their patience tested with the guitarist’s Soundscapes series, which ranges from atonal ambience to peaceful meditations like Sky.

The track, the final movement from his live Buenos Aires Suite, is masterfully constructed, each sliver of tone bleeding in a color, like sun pouring in through a stained-glass window. By the piece’s end, you’ve lost all sense of timing and chord sequence, just allowing yourself to soar through the kaleidoscope.

19. The Zero of the Signified: Robert Fripp, from 1980’s God Save the Queen/Under Heavy Manners

Fripp continued to refine his Frippertronic experiments on his second solo LP – and he pushes hardest on its funkier second side, Under Heavy Manners, combining layered guitar textures and driving, four-on-the-floor rhythm sections into a style he dubbed “Discotronics.”

At just under 13 minutes, closer The Zero of the Dignified isn’t exactly an easy listen – the ever-repeating lead guitar lick, a six-note motif similar to the cyclical pattern on King Crimson’s Frame by Frame, is a catalyst for hypnosis or anxiety, depending on one’s mood.

But the entire guitar arrangement is subtly, almost subconsciously, cinematic, as those industrial-tinged loops zoom past like menacing storm clouds.

18. I Advance Masked: Andy Summers & Robert Fripp, from 1982’s I Advance Masked

It may seem like an unlikely pairing on paper, but Fripp and Police guitarist Andy Summers found a fascinating stylistic middle ground on I Advance Masked, the first of the pair’s two collaborative LPs.

The centerpiece is the opening title track, contrasting Summers’ chiming Synchronicity-era tones with Fripp’s dizzying chromatic runs over a muted kick drum pulse. “I would say the I Advance Masked album,” Fripp told Guitar Player in 1986, “was a matter of research and development and arts and crafts, and of professional musicians working honorably.”

No doubt about that. It’s familiar territory for both of them, but the record occupies its own unique little corner in both of their catalogs.

17. Upon This Earth: David Sylvian, from 1986’s Gone to Earth

Fripp found a simpatico collaborator in David Sylvian, former frontman of art-pop band Japan; they worked together on multiple tours and even recorded a 1993 LP, The First Day, billed under both of their names.

But Fripp also added some reliably evocative guitar to Sylvian’s sprawling double-LP Gone to Earth, including an array of atmospheric tones on Upon This Earth. Over a reverb-smothered two-chord pattern of slide guitar and piano, the Crimson leader squeaks out some pristine birdsong that elevates the track into the stratosphere.

16. Hammond Song: The Roches, from 1979’s The Roches

Fripp was wildly prolific during the break between King Crimson’s 1974 disbandment and 1981 reinvention: recording solo work, making plenty of studio cameos, producing a handful of classic records. In one of his oft-forgotten collaborations, he helmed The Roches, the American folk-rock trio’s self-titled debut – a project that arose after Fripp saw the group perform in New York and, impressed by what he saw, volunteered his services.

His instrumental touch is minimal throughout the album, mostly relegated to occasional ambiance. But one standout contribution, the breathtaking guitar break on Hammond Song, is a highlight from the entire pre/post-Crimson era.

His understated solo, a series of snaking patterns and sustained tones (cutely credited here as “Fripperies”), brings a glimpse of the ethereal to an otherwise earthly ballad. (Bonus factoid: Levin, the guitarist’s future bandmate, also appears on The Roches, giving King Crimson diehards another reason to seek this one out.)

15. Heroes: David Bowie, from 1977’s Heroes

It could be Bowie’s crowning achievement, but Heroes wouldn’t reach such lofty heights without Fripp’s subtle, yet essential, guitar work. Compared to the ornate Frippertronics or rapid-fire picking that define much of his catalog, the two-note phrase at this song’s core might seem pedestrian by comparison.

But it’s hard to imagine a guitarist drawing out more emotion from those two notes – sustained bursts of tone that are essentially as famous as Bowie’s own vocal melody. And it’s not like Fripp just tossed off his cameo; as producer Tony Visconti told Sound on Sound, he used a “fine science” to craft his part, measuring the distance between his guitar and the speaker to create a perfect feedback for each note he played.

14. Sartori in Tangier: King Crimson, from 1982’s Beat

Of King Crimson’s early ’80s trilogy, Beat is often the most overlooked – arriving after the bold New Wave-prog evolution of Discipline, this album was naturally a little less radical.

But the band continued to experiment with fascinating results: Take, for example, the instrumental Sartori in Tangier, in which Fripp’s violin-like leads pirouette over the hypnotically funky groove built on Levin’s thumping Chapman Stick and Bill Bruford’s clacking percussion.

It sounds like no other Crimson song – or really any other song, period. “The music was very stage-friendly,” Bruford told the DGM site. “[I]t had its own internal musical drama which worked well in that environment and it was a complete groove to play live. Nightly I could look forward to Robert’s solo at the end of [Sartori in Tangier].”

13. Evening Star: Fripp & Eno, from 1975’s Evening Star

On their second collaborative project, Fripp and Eno saved their most experimental tendencies for the six-part, 28-minute closer An Index of Metals. But side one is soothing and placid, particularly on the twinkling title track: Fripp’s sustained leads bob calmly amid the waves of clean strumming and pinging harmonics, occasionally joined by Eno’s synths. It’s an atmosphere as serene as the misty mountain-like landscape on the album cover.

12. Baby’s on Fire: Brian Eno, from 1974’s Here Come the Warm Jets

Brian Eno ratchets up the tension throughout this warped glam-pop oddity, singing bratty lines over a tick-tock hi-hat and out-of-tune, two-chord pulse that slowly worms its way under your skin.

It’s unsettling and somewhat hilarious, but the song achieves classic status only through Fripp’s contribution: he goes wild as the piece grinds on, sparking off some of his most conventionally bluesy and metallic playing, adding feedback and seasick bent notes to the recipe.

11. Swastika Girls II: Fripp & Eno, from 1973’s (No Pussyfooting)

Swastika Girls II is like the evil cousin of The Heavenly Music Corporation, closing out (No Pussyfooting), Fripp’s debut collaboration with ambient master Eno, with a transcendental swath of VSC-3 synthesizer, clean picking and laser-beam leads.

The guitarist’s showpiece solo, laid out over the duo’s signature tape loops, is both evocative and discordant, occasionally adopting an Eastern feel.

Radical stuff – and it apparently arose in the magic of the moment: “Brian set up the looping in the control booth,” he wrote in his DGM Live diary, “and, after five minutes of listening to the looping playing in to the multi-track, I walked into the studio, strapped on [and] wailed out.”

10. Breathless: Robert Fripp, from 1979’s Exposure

Breathless is a lost classic in the Fripp oeuvre, a stylistic hybrid between the metallic crunch of King Crimson’s Red, the textural soundscapes of his Eno collaborations and the sort of New Wave-leaning sleekness he’d perfect with Crimson’s ’80s lineup in just a couple years.

Few of his riffs punch with such heavyweight force, ascending the scale over the funky, bombastic rhythm section of drummer Narada Michael Walden and bassist/future bandmate Levin. Fripp is clearly fond of the tune, having revived it onstage in 2017 with Crimson’s triple-drummer lineup.

9. Exiles: King Crimson, from 1973’s Larks’ Tongues in Aspic

This starlit ballad is one of the few ’70s Crimson tunes not dominated by Fripp’s electric guitar. But that’s precisely what makes it such a balanced tune, allowing plenty of space for Mellotron, John Wetton’s melodic bass and almost-too-high-for-his-range belting, David Cross’s violin and Bruford’s minimalist drumming.

Fripp mostly sticks to the acoustic, a rarity for this era – and his sublime arpeggios add a sense of poignancy that fits the track. Of course, he also squeezes in a tasteful electric solo at the end – the icing on this multi-layered cake.

8. Starless: King Crimson, from 1974’s Red

Red’s 12-minute closing epic fell dangerously close to the cutting room floor – according to Wetton, Fripp and Bruford weren’t impressed with the initial version presented during rehearsal for 1974’s Starless and Bible Black. (A meandering instrumental essentially took that song’s place on the record.)

But after some expanding the sax-laced ballad with some new, menacing sections and workshopping the tune onstage, Starless wound up as a classic in the Crim oeuvre.

Fripp covers a wide stylistic range here: tackling the haunting main theme, ratcheting up the tension midway through with a series of one-note phrases in two-string bundles, adding some jarring riffs that sound like error messages from malfunctioning robots.

7. The Night Watch: King Crimson, from 1974’s Starless and Bible Black

It’s a lost Crimson masterpiece, arriving midway through one of the band’s strangest and most misunderstood albums, Starless and Bible Black.

Much of that project was built on improvised live recordings that were later tweaked and augmented in the studio – and as such, long stretches of its runtime are challenging to traditional prog fans, defined by loose instrumental explorations more than conventional riffs and choruses.

But The Night Watch is an exception to that meandering vibe – a showcase for King Crimson’s melodic side and wide band dynamics. Cross’ weepy violin and Wetton’s melancholy vocal grab you immediately, but Fripp is the MVP: he opens with frenzied tremolo strumming that dissolves into gorgeous harmonics and sweeping, vibrato-heavy leads.

6. 21st Century Schizoid Man: King Crimson, from 1969’s In the Court of the Crimson King

Robert Fripp’s legend was born with 21st Century Schizoid Man, the iconic opening track from King Crimson’s debut LP. Of course, the strength lies in the full-band attack – from Michael Giles’ spasmodic drum fills to Ian McDonald’s menacing saxophones to Greg Lake’s throat-ripping vocal to Peter Sinfield’s war-torn lyric.

“For me, it was group writing,” Fripp told Rolling Stone in 2019. “And it wouldn’t have been possible without those five young men.” But Fripp’s guitar is certainly on fire here, whether it’s firing off chunky chords, screaming in unison with Lake’s opening bass riff or gliding through the jazzy section with fuzzy leads and palm-muted melodies.

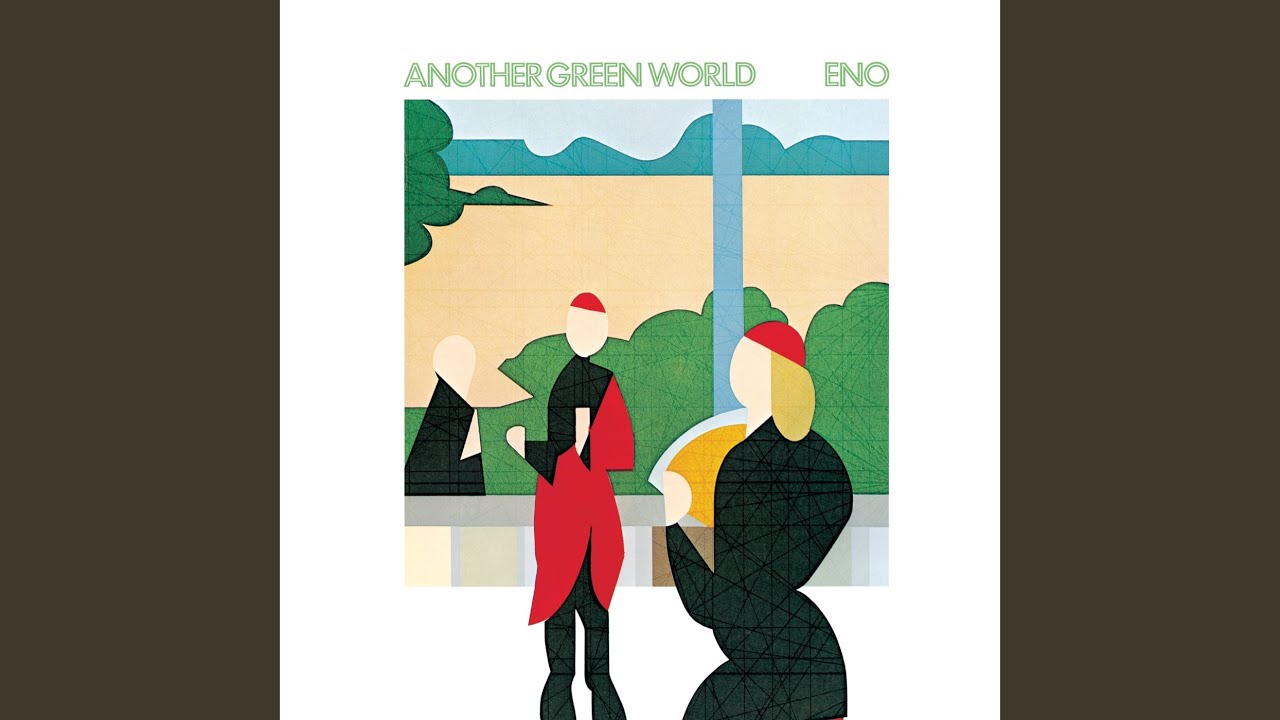

5. St. Elmo’s Fire: Eno, from 1975’s Another Green World

Few musicians think more conceptually about sound than Eno. Legend has it that, while recording this oceanic art-pop tune, he challenged Fripp to channel the sound of a Wimshurst machine, the electrostatic generator created in the late 1800s.

Whether or not he succeeded in that task is irrelevant: Eno’s unique request prompted one of the guitarist’s most thunderous, violently aggressive solos – a torrential downpour of notes that balances out the song’s overall sweetness. (On the final LP sleeve, he was credited with “Wimshurst guitar”.)

4. Level Five: King Crimson, from 2003’s The Power to Believe

By 2003, Fripp and Belew had crystallized a distinctive guitar symmetry, a sort of sonic telepathy refined through years of rehearsal and performance. King Crimson’s 13th LP, The Power to Believe, featured many of their signature moves, including a more aggressive, textured take on the interlocking style they’d perfected in the early ’80s.

And Level Five is the pinnacle of their work in this more metallic arena: Check out how they harmonize in the first verse and enter into a lockstep back and forth over Pat Mastelotto’s glitchy electronic percussion, followed by chunky call-and-response riffs and ascending shredding.

3. Larks’ Tongues in Aspic, Part Two: King Crimson, from 1973’s Larks’ Tongues in Aspic

“The question I posed myself might be put like this: ‘What would Hendrix sound like playing the ROS or a Bartok string quartet?’” Fripp wrote in his online diary in 2001. It’s an audacious query – and it resulted in one of King Crimson’s most distinctive achievements: the two-part piece that bookends the band’s fifth LP.

The second half is the heart-stopper: Fripp piles up sheets of distortion that rise and fall in intensity, his instrument often interwoven with Cross’s violin and Wetton’s bass to create a snarling monster of strings.

“If an older man might look back at this and be struck by that young man’s arrogance,” Fripp wrote, “well, an ignorance of limitations sometimes allows the young of any age to achieve impossible things!”

2. Frame by Frame: King Crimson, from 1981’s Discipline

When Fripp answered the call of King Crimson in the early ’80s, he found himself operating with a new array of influences and sonic tools: the at-turns delicate and quirky vocal stylings of Belew, Levin’s octave-spanning Chapman Stick, the possibilities of a dual-guitar attack, the gloss of New Wave and the interwoven ensemble complexity derived from gamelan music.

Frame by Frame is an essential showcase for all of the above, with Fripp and Belew teaming for a brain-rattling pattern where the guitarists briefly diverge into two different meters, only to align once more.

1. Fracture: King Crimson, from 1974’s Starless and Bible Black

“Fracture is impossible to play,” Fripp wrote in his online diary in 2016. For most people, that’s 100 percent accurate. But Fripp is not most people: he mastered the 11-minute instrumental for King Crimson’s sixth studio LP, and he’s played it dozens of times onstage – a remarkable feat of mental, physical and perhaps even psychological endurance.

The crux of Fracture, of course, is the three-minute section featuring his “moto perpetuo” (“perpetual motion”) technique, wherein his flurries of string-skipped notes unfurl over a dynamic rhythm section.

Fracture may not be “impossible to play”, but it’s been a challenge, even for Fripp: “It took a year to bring my [practicing] up to speed, as it were,” he wrote, “and four months directly and specifically on Fracture. My wife had quite enough after a few weeks, so I had to lock the door to the cellar where I practice.”

Staying in Fracture-ready shape may be a lifelong commitment – but all that matters is that he nailed it in the studio. One of rock’s most technically challenging pieces never sounds like rote muscle-flexing – in Fripp’s busy hands, the whiplash comes off as graceful.

Ryan Reed is a Knoxville, Tennessee-based writer, editor, musician, record collector, prog junkie, and former college professor. In addition to Guitar World, he's a contributor at SPIN (current title: senior editor), Rolling Stone, TIDAL, Relix, Ultimate Classic Rock, Revolver, and many other outlets. He's also the author of 2018’s Fleetwood Mac FAQ: All That’s Left to Know About the Iconic Rock Survivors.