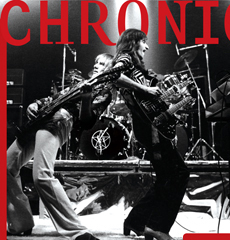

Rush: Chronicles

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Through more than 33 years Rush has remained the ultimate prog-rock powerhouse. Guitar World presents the history of the group that blended high-pitched vocals, extended instrumentals, sci-fi imagery and keyboards and somehow made it all work.

In 1974, when Rush released a self-titled album on their own tiny label, nobody imagined that this little-known Toronto power trio would last another three decades, much less that it would become one of the most influential names in hard rock. Thirty-four years later, however, Rush are an institution, with 25 albums (not counting compilations) under their belt and more than 40 million in worldwide sales.

But those numbers tell only part of the story, for the importance of Rush cannot be measured in sales alone. As the trio moved from the bluesy basics of “Working Man” to the progressive metal of “2112,” “A Farewell to Kings” and “La Villa Strangiato,” it raised the bar for mainstream rock, both in terms of creativity and technical ability. Learning to play Rush songs was a way for younger musicians to prove their mettle, and as such the band became an influence on a whole generation of rockers, from Dream Theater to Metallica, from Smashing Pumpkins to Stone Temple Pilots, and from Primus to Rage Against the Machine.

Then again, Rush themselves started out in the late Sixties as just another group of teenage hopefuls. Bassist and singer Geddy Lee first met guitarist Alex Lifeson when the two were seventh graders, growing up in the north Toronto suburb of Willowdale. “He was in my class in grade seven,” Lee recalls. “He was playing in this band called Rush. It was him, [drummer] John Rutsey and a bass player named Jeff Jones.”

Lifeson’s band had a regular Friday gig at a coffeehouse run by a local church. “He used to call me up but more to borrow equipment from me than to actually jam, because he was a famous mooch back then,” Lee says. “Then he called me up—it was, like, Friday morning—and said, ‘Our bass player can’t make this gig tonight. Do you want to fill in?’

“I said, ‘Sure.’”

Lee quickly went from filling in to playing as a fulltime member. Rush spent their earliest days playing youth centers and high school dances all around Ontario. Then, in 1971, Ontario lowered its drinking age to 18. “We were 18,” Lee recalls. “And that opened a whole world of drunkenness to us. And bar gigs.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Over the next two years, Rush slowly built an audience, working their way up the Toronto bar circuit, from tiny Yorkville dives to rock palaces like the Gasworks (which would later cameo as the club in Wayne’s World). Along the way, the group picked up manager Ray Danniels, who was determined to build the band into something bigger. “In order to get us out of the bars, he and his partner decided to become promoters,” Lee explains. “They started putting on shows at the Victory Burlesque Theatre on Spadina, which is gone now.” Their first booking, in October 1973, was opening for the ultra-glam New York Dolls.

Danniels also took a do-it-yourself approach to getting Rush a record deal. He had the band do its recording in the hours after its regular club gigs—studio time was cheaper in the dead of night. When the finished master was turned down by every label in Canada, Danniels put together a label of his own, Moon Records, to release Rush.

Somehow, a copy of the album got to WMMS in Cleveland, where DJ Donna Halper put “Working Man” into heavy rotation. “The phones were going crazy,” Lee recalls. Super-manager Cliff Bernstein (Metallica, Def Leppard, Red Hot Chili Peppers), who was then just an A&R man at Mercury Records, picked up on the buzz and got Rush signed. Suddenly, the band had both an audience south of the border and an international record deal.

“And then,” Lee says, “our drummer quit.” John Rutsey may have been in the band longer, but it was Lee who had forged the stronger connection musically with Lifeson, sharing the guitarist’s interest in the more progressive sounds of Yes, King Crimson and Jethro Tull. Rutsey, by contrast, was more of a rock and roll purist, according to Lee. “He was a different kind of rocker, and that was becoming more apparent with the new material we were working on.” Worse, Rutsey had no interest in touring, so when the Mercury deal raised the prospect of touring the U.S., Rutsey made for the door.

Needing a new drummer fast, Rush held auditions and quickly found Neil Peart, who at the time had been working for his father’s tractor company in St. Catherines, Ontario. Peart may have looked a bit square compared to Lifeson and Lee, but the way he played made it clear that he was on the same wavelength. Peart joined Rush at the end of July 1974, and within a couple weeks was onstage at an arena in Pittsburg, where Rush opened for Uriah Heep.

This new lineup toured steadily through the new year, taking just a week off in January to record its sophomore album, Fly by Night. Although the young band’s Zeppelin-isms were still very much in evidence, especially in Lee’s muscular, bluesy vocals, the playing was tighter and more virtuosic as Peart’s drumming locked firmly with the guitar and bass. Rush toured extensively and did quite a few shows with Kiss, during which the two young bands became close friends.

But where Kiss were moving steadily toward the mainstream, the members of Rush wanted to go in their own direction. Caress of Steel, released just seven months after Fly by Night, pushed the band deep into prog-rock territory, what with the medieval fantasy bound up in “The Necromancer” and a rambling, 20-minute opus dubbed “The Fountain of Lamneth.” Where Fly by Night eventually broke the million-seller mark, Caress of Steel was a commercial setback that was mocked by the music press. Although the band continued to build an audience through its live show, its third album was widely considered a step in the wrong direction.

Not by Rush, however. Their follow-up, 2112, continued in the direction of its predecessor, and its success proved that prog was definitely the right path for Rush. As with Caress of Steel, the emphasis was on grand gestures and big ideas, with the sidelong “2112 Suite”—a futuristic fantasy with words by Peart and music by Lifeson and Lee—standing as the band’s first avowed masterwork. The album also clicked with audiences, and within a year earned the band its first Gold record.

But 2112 was important for another reason. According to Martin Popoff’s Rush biography, Contents Under Pressure, the three members discussed expanding the band’s lineup when making 2112 in order to add keyboards and other instrumentation; instead, they decided to double on other instruments. Thus, when it came time for Lifeson’s solo in “A Passage to Bangkok,” Lee—who would be playing a double-neck Rickenbacker—would switch to rhythm guitar while covering the bass part using a Moog Taurus synth, which consisted of an 18-note pedal board. This early move toward multitasking would later become a major part of the band’s performance practice.

2112 was the first Rush album to crack the top 100 of the Billboard Albums chart, but it was All the World’s a Stage—a live album recorded at Toronto’s Massey Hall that same year—that finally put the band in the Top 40. Perhaps that’s why the band felt it could take some time to make its next album, A Farewell to Kings. Recorded over the course of several weeks at Rockfield studios in Wales, the album featured a much broader range of tones than Rush’s previous albums, incorporating everything from synthesizer to troubadour-style acoustic guitar flourishes to orchestral bells. Stylistically, it alternated between epic rockers “Xanadu” and “Cygnus X-1” and short, tuneful numbers like “Closer to the Heart.”

By this point, Rush were headlining gigs, and they toured mercilessly, often driving as much as 200 miles between gigs (and in those days, the band members still shared in the driving). But their efforts paid off; Farewell sold even better than 2112, thanks in part to the radio play garnered by “Closer to the Heart.” The band followed in 1978 with Hemispheres, “probably our most prog album,” Lee says. In addition to continuing the “Cygnus” saga with the 18-minute suite “Cygnus X-1 Book II: Hemispheres,” the album included the nine-minute instrumental “La Villa Strangiato.”

Then it was time for something completely different.

Much as punk rock arose in part as a reaction against the perceived excess of progressive rock, 1980’s Permanent Waves was meant as Rush’s response to the fashion-driven lockstep mentality of late-Seventies new wave. At the same time, it marked Rush’s break with heavy prog, as the band’s sound grew lighter, less cumbersome and more reliant on synths. Though Rush hadn’t exactly simplified their sound—“Freewill,” one of the album’s most popular tunes, is mostly in 13/4 meter—their focus was definitely different from what it had been previously.

The audience began to change as well. Thanks to the reggae-tinged, Simon & Garfunkel–quoting song “The Spirit of Radio,” Rush were finally beginning to develop a pop profile. But it wasn’t until the following year, with Movng Pictures, that Rush really hit the big time. Between the pop smarts of the hit single “Tom Sawyer” and the tuneful intricacy of FM-friendly fare such as “Limelight” and the instrumental “YYZ,” Rush had come up with the perfect blend of the old wave and the new wave, the epic and the pithy, the visceral and the cerebral. It was the band’s biggest-selling album, a quadruple- Platinum smash.

Not surprisingly, this stemmed in part from a change in the band’s writing practices. “I started writing parts on keyboards,” Lee explains, “just to add more sound, texture and melody. I just thought it would be interesting to bring more noises into the band.” But the keyboards didn’t simply add “more noises”—they also brought a new sense of space into the arrangements, one that led to changes in Lifeson’s palette of guitar tones and Peart’s use of percussion.

Exit…Stage Left, the band’s second live album, followed quickly, and then it was back into the studio to record the synth-heavy Signals. By this point, rock’s new wave had evolved from the skinny-tie simplicity of the Knack to the more complex sound of Peter Gabriel, Thomas Dolby and Ultravox, and Rush’s sound seemed to be evolving in tandem. Lee’s keyboards often dominated the mix, while Lifeson’s guitars turned to chorus and flange more than to distortion. Diehard Rush fans complained mightily about the band’s new sheen, but it didn’t seem to hurt Rush on the charts. Signals quickly went Platinum, while “New World Man” became the trio’s highest-charting single.

By this point, Rush had settled comfortably into the ranks of arena headliners, regularly playing to audiences of 18,000 a night. Although the band would never match the commercial success of Movng Pictures, it would enjoy impressively consistent popularity through the early Eighties, with each of the four albums after Pictures going Platinum and peaking at No. 10 on the Billboard album charts.

That’s not to say it was smooth sailing on the creative end. Grace Under Pressure, from 1984, was originally to have been produced by Steve Lillywhite, who had overseen breakthrough albums by U2, Peter Gabriel and Big Country. But Lillywhite bailed out at the last minute, opting instead to work with Simple Minds, which left Rush to coproduce the album with engineer Peter Henderson. Although Grace made significant moves toward restoring the balance between keyboards and guitar (and found Peart experimenting impressively with reggae rhythms), it was nowhere near as polished or confident as its follow-up, 1985’s Power Windows, on which the band, spurred by Lee’s reinvigorated bass work, played in a much more aggressive style. This time, Peter Collins was behind the board, and his production style seemed perfectly suited to the band’s mindset. “We were much more interested in song arrangement and all of that, which is absolutely his forte,” Peart told Popoff.

But Hold Your Fire, from 1987, seemed to break that momentum. Some of it had to do with the material, which the band described as “introspective,” and which was at points sweetened by strings, additional keyboards (provided by Steven Margoshes) and, on “Time Stand Still,” backing vocals (by Aimee Mann of ’Til Tuesday). Mainly, however, it seemed as if another era in the Rush saga was drawing to a close. The band had largely met its obligation to Mercury Records—Hold Your Fire would be followed by a live album, A Show of Hands, as well as the double-disc retrospective Chronicles—and was moving away from keyboards as a central part of the Rush sound.

A Show of Hands did, at least, document the extent to which technology had changed the Rush live show. The three band members had begun using sequencers for some of the songs from Movng Pictures, and by the late Eighties they were making extensive use of samplers to trigger additional instrumental parts. Meanwhile, on the Grace Under Pressure tour, Peart had begun to use the “360 Degree” drum kit, which broadened his percussive range by surrounding him completely with drums and electronic percussion.

For 1989’s Presto, Rush moved to Atlantic Records and shared production duties with Rupert Hine (Tina Turner, Thompson Twins). In many ways, the album was transitional: Rush had gained more creative control, thanks to their new label, and had begun taking a new approach to songwriting. Where once the material had been written piecemeal, with melodic ideas stitched together by sometimes hastily written transitions, the songs on Presto were made of whole cloth, more like traditional pop tunes. It wasn’t an overtly commercial move—although “Show Don’t Tell” did make it to No. 1 on the Billboard Mainstream Rock chart—but it definitely changed the sound and feel of Rush’s writing.

Roll the Bones pushed that sense of experimentation further still, with African rhythms sprinkled through the track “Heresy” and even a bit of rap in the title tune, but that hardly phased the fans. Indeed, the album turned out to be the band’s biggest seller since Movng Pictures, and the tour—which included a sequence with an animated skull doing the title tune’s rap—set a new standard for musicianship and spectacle.

Or course, Rush being Rush, a turn toward pop would naturally be followed by a move in the opposite direction, and so Counterparts shoved the keyboards aside and cranked the guitars, particularly on tracks such as “Stick It Out.” But after two decades of releasing an album a year or every other year, the band was beginning to slow down, and there was a three-anda- half-year gap between Counterparts, in 1993, and its follow-up, 1996’s Test for Echo.

Not that the band had changed much in the interim. Although Lee spoke at the time of being impressed by Soundgarden and Smashing Pumpkins, Echo was a logical step forward from Counterparts in terms of its sonic aggression and high-impact virtuosity. (It probably didn’t hurt that Peart had recorded a Buddy Rich tribute album during the band break.) Perhaps the biggest change had to do with touring practices, as Rush had begun performing two sets, with no opening act.

Then tragedy struck. In August 1997, Peart’s teenage daughter, Selena Taylor, was killed in a traffic accident. The following year, his wife died of cancer. Understandably, Rush went on hiatus, and there were some who worried that the band was gone for good.

But the band did return, five years later, with Vapor Trails. “We had a lot of musical reuniting to do,” Lee said at the time, and making the album was a long and occasionally awkward process. But it also led to a sense of rediscovery within the band, as each of the three developed a newfound respect for the others’ strengths and musicianship. Nowhere was that more apparent than on the subsequent tour, which was memorably documented in the quintuple-Platinum video Rush in Rio.

In 2004, Rush celebrated the 30th anniversary of their record debut with Feedback, an EP of cover tunes, many of which the band had performed in its youth. Feedback was a blast from the past in more ways than one. “We played live on the floor,” Lee explains, “which was the first time we’d done that for an album in quite some time. It was just, ‘Let’s play these songs.’ ” Naturally, there was a worldwide anniversary tour and, eventually, a concert video: R30: 30th Anniversary World Tour.

By the time the band got back into the studio to make Snakes and Arrows, its 18th studio album, in late 2006, Lifeson, Lee and Peart were back in the old groove. The album was written on acoustic guitar—“the way we used to write, you know, 15, 20 years ago,” according to Lee—and emphasized the players’ virtuosity while it maintained a sense of song structure. It was, in other words, classic Rush, with every indication of more to come.