“I bought my first solidbody electric from Ed King. It was a Gibson SG he’d used as his main guitar in Strawberry Alarm Clock”: Steve Bartek was Danny Elfman’s right-hand man for Oingo Boingo and countless movie scores – now he’s playing Coachella

The new wave guitar hero reflects on his early days with future Lynyrd Skynyrd guitarist Ed King, how playing flute influenced his guitar playing, and his upcoming shows with Danny Elfman

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

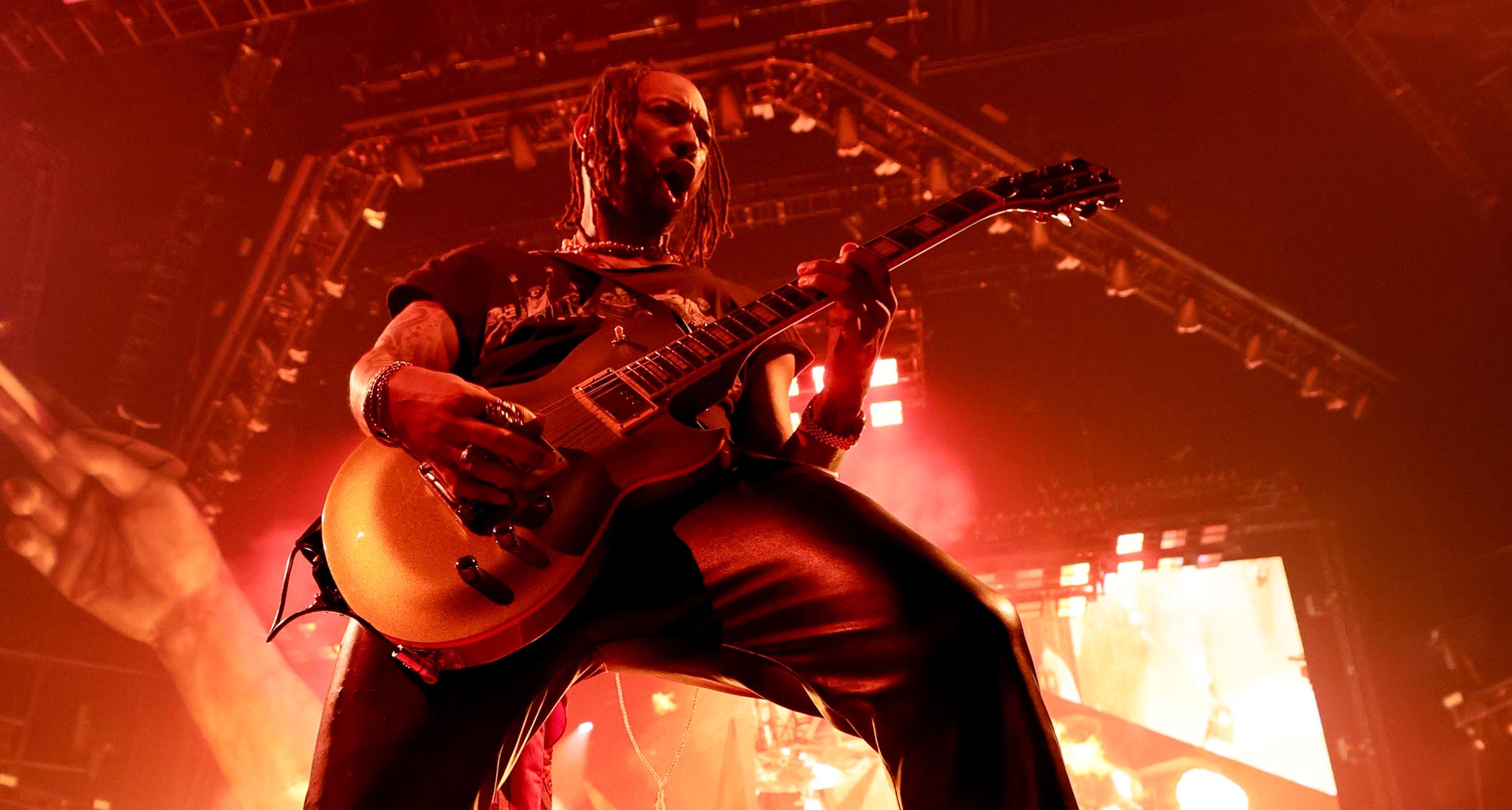

Guitar heroes come in all shapes and sizes, but the imagery often associated with the “greatest” axe-slingers always seems to coincide with bombast, pomp and circumstance. But there’s another side to the coin. Don’t believe us? Just ask former Oingo Boingo six-stringer Steve Bartek.

Throughout the ’80s, Bartek played sideman to Boingo’s founder, vocalist and primary songwriter, Danny Elfman. And if the duo’s exploits had stopped there, their legend as champions of all things quirky and alternative would be set in stone. But in truth, cuts such as Weird Science, Fool’s Paradise and Dead Man’s Party were just the tip of their musical iceberg.

“The chemistry between Danny and me was immediate,” Bartek tells Guitar World. “It was the kind of thing where we connected on many levels. We had similar musical interests and loved injecting ethnic elements into our work. And Danny had ventured to Africa and brought back all these African instruments, some of which we used on our albums. So we had a shared mindset for sure.”

Elfman was a deft songwriter and inventive multi-instrumentalist. But without Bartek, who “filled the gaps” in Elfman’s seemingly endless creativity, what happened post-Boingo might never have come to pass. And what happened was a succession of hyper-successful film and television scores such as Back to School, Beetlejuice, The Simpsons, Edward Scissorhands and so much more.

It makes sense, given the eclectic nature of Bartek’s resume. He’d gone from a teenager playing flute in psych-rock band Strawberry Alarm Clock to slinging Ed King’s Gibson SG to unleashing unruly yet jangly riffs with Oingo Boingo – so why wouldn’t he make the jump to helping score some of the most significant films in history?

Still, despite his immense success, Bartek keeps a level head when articulating his longevity in a business that thrives on chewing up and spitting people out: “Longevity is a tough thing to sort out. I’m still here because I’ve always insisted on trying things that seem just out of my reach. I like to push myself, and doing so still excites me.”

“I’ve thrived while doing things that I never thought I’d be called on to do,” he adds. “And each time that happens, I say, ‘Well, I can’t do that.’ But then I force myself, and it works out. I’ve always had to push away the temptation to say, ‘Hey, I’m just a guitar player; I shouldn’t do that,’ I learned a long time ago that I need to be prepared to do anything to survive as a musician. And so, if an opportunity arises, and it makes sense, I go for it.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

The flute allowed me to approach the guitar from a more melodic sense

What inspired you to first pick up the guitar?

“It was probably the Beatles. But I have to say I was a flute player before I heard them. But then the Beatles showed up, spurring my brother and me to pick up the guitar.”

Your style has always struck me as unique. Did the flute inform how you approached the guitar?

“I think, in retrospect, yes. Because I took flute lessons from third to sixth grade, I had a concept of music notation, melody and everything else. So when I took up the guitar when I was 11 or 12, I think I looked at it slightly differently than other young kids at that time.

“From the beginning, I was told, ‘Steve, you’re looking at the guitar as if you’re playing the flute,’ which I don’t think was bad. The flute allowed me to approach the guitar from a more melodic sense, which, admittedly, is sometimes hard to find in my old recordings. But I like to think of myself as a melodic player, and I think my early training on the flute certainly lent itself to that.”

How did you become involved with Strawberry Alarm Clock?

“Right around the time I started playing guitar, my neighbor was George [Bunnell], and he asked me if I’d like to record with this band that he was starting, along with a few other guys, called Strawberry Alarm Clock. So, I went down and played flute on four or five songs while they were recording the first album. But the funny thing was my mom wouldn’t let me officially join the band because I was only 15. [Laughs]”

But you still managed to grab four writing credits, including Birds in My Tree, Strawberries Mean Love, Rainy Day Mushroom Pillow and Paxton’s Backstreet Carnival.

“That was incredible for a young kid like me. I remember George and I would sit in my bedroom, find phrases or things from books or song titles and write songs. I’d say we wrote maybe a dozen songs or so, and it just so happened that Strawberry Alarm Clock needed four for the album.

“So we played them all for the rest of the band, and they recorded them. But they changed the titles to more psychedelic things, as you mentioned. The songs we wrote had nothing to do with strawberries; that was about incorporating that whole vibe into the songs.”

Ed King, who later went on to play with Lynyrd Skynyrd, notably played in Strawberry Alarm Clock. Did his style impact you?

“I think it did. I didn’t think much of it at the time, but being around Ed certainly did impact me. And something a lot of people don’t know is that I bought my first solidbody electric from Ed.

“It was a Gibson SG that he’d used as his main guitar in Strawberry Alarm Clock. He used it during the double guitar solo in Strawberries Mean Love and for many other things. And speaking of that solo, I think it impacted me significantly. The idea of interacting with another guitar player became a big part of my life.”

Did you use that SG on any notable recordings, and do you still have it?

“No. I got the guitar before I could do any substantial recordings. And again, no, I don’t have it anymore. I wish I did, but I gave it to a friend who was down and out and has since disappeared.

“But I also gave it away because while I thought it sounded great and felt pretty good, I was a very aggressive player. So if I bent the neck a bit or got overexcited, the guitar would easily fall out of tune. At the time, it seemed like an instrument that would constantly go south on me, but now I wholly regret letting it go.”

How did you meet Danny Elfman?

“I was friends with a guy named Peter Gordon, the brother of Josh Gordon, who played trumpet in Boingo from ’73-75. Josh was playing with a theater group called the Mystic Knights of the Oingo Boingo, and they needed a guitar player. The guy they had before me – whose name I can’t remember – was basically a Django Reinhardt specialist.

“But Danny was trying to turn Mystic Knights into a group that could handle doing theaters. So Josh auditioned, and I found they needed a guitar player through him. I auditioned for Danny, and… the rest is history.”

Danny trusted me... we had a shared mindset, so he’d be writing songs, and then he’d ask me what I thought – and there’d be this back and forth

Considering your history with the flute and Boingo’s theatrical tendencies, how did you best impact the band from a guitar perspective?

“Danny trusted me and shared some of the responsibility of ensuring we had something the band could play. Again, we had a shared mindset, so he’d be writing songs, and then he’d ask me what I thought – and there’d be this back and forth.

“I ended up writing most of our horn parts and ensuring all of that was in order when it came to rehearsal. So Danny trusted me to help him communicate what he wanted and to help form his songs in the early stages.

“And that informed how I approached my guitar parts. The fact that I had a technical background and knowledge probably filled up some of the holes within Danny’s creativity.”

Dead Man’s Party is perhaps Oingo Boingo’s most well-known album, and Weird Science is probably its most famous track. Do you remember putting it together?

“That was actually a very fun one to do. I remember having to detune my guitar to play that little riff and the hook in the middle because I had to play it down one octave. And then the fun of being able to jam out on the end and do all kinds of wild stuff was terrific.

“I also recall we wanted to do a sort of dance version, so it was a one-off deal. It came together quickly; the whole song took one or two days.

Dead Man’s Party features an extremely quirky riff. Did you or Danny write that?

“That one was Danny’s composition. I think he started that tune with a drum machine and then based the whole thing on some African Highlife stuff he’d heard while traveling through Mali. I then added the horn stuff, and we banged it out as a band. But Danny had made a sequence with his little drum machine that had custom sounds that he created himself, and that’s where that riff spawned from. And the bass part is composed of a continuous bass loop that keeps going, which I think is part of the unusual and disarming nature of the song.”

What guitar did you use for the Dead Man’s Party sessions?

“My main guitar at that point was mainly a Les Paul. I had a ’69 goldtop reissue with some deluxe pickups. Not the high-output pickups, but the smaller humbucking pickups.

“I think that guitar was great for songs like Dead Man’s Party because it gave me a much cleaner tone – even though I turned up the amp for the introduction to make it more distorted for the first riff on the recorded version. But the rest of the album is all fairly clean guitars, which was intentional, to emulate that African Highlife style that Danny was shooting for.”

Going back to Dead Man’s Party and Weird Science, I had just gotten a Mac, and I remember trying to write out all the arrangements on that, which was major technology in the Eighties

How did you manage to balance all those horn arrangements with your duties on guitar?

“That’s a good question, but I have no idea. [Laughs] I guess I did what I thought was right and felt good. Going back to Dead Man’s Party and Weird Science, I had just gotten a Mac, and I remember trying to write out all the arrangements on that, which was major technology in the Eighties.

“I had this really crude software that let me write it all out, but because it was so crude, mistakes did happen. I accidentally wrote an eighth note, and when it came in, I listened to it and went, “Oh, I’m glad I made that mistake; I like that much better.”

Oingo Boingo was notably featured in Rodney Dangerfield’s cult 1986 comedy, Back to School. What was that experience like?

“As I recall, Danny was hired to do the score, and I think we did the live performance because of that. But I could be remembering wrong, meaning we might have been hired to do the appearance and then the score stemmed from that. [Laughs]

“That aside, working with Danny on that score was a lot of fun. It was the second ‘bigger’ film score we’d worked on, and I thought I’d be a smart aleck. So what I did was try and do what’s called a ‘transpose score,’ and – long story short – I failed. A lot of questions and crap came from that to the point that I never tried to do that again. That’s my greatest memory of that whole thing.”

Can you explain to us what did go wrong, specifically?

“It would be easier just to ask what I hated about it. [Laughs] That’s a tough one because there were so many wrong things. But there were also things that I thought were wrong, but ended up being right. And that’s a theme that followed me even when Danny and I did the Beetlejuice and Batman scores.

“But I remember the first day we had a famous conductor there, and he was just tearing apart everything we did to the point that I was almost in tears. And this was early on, and I looked at the page and was just like, ‘Everything is wrong. I did this completely wrong.’ But luckily, Danny ended up firing the guy and everything was fine. But before that, all I could think was, ‘Man… I really fucked up.’”

Fortunately, my career trajectory has allowed me to not just be a guitar player. I’m not sure where I’d be if it didn’t happen that way

Is there a dividing line between being a composer and a guitarist for you?

“There might have been in the past, but I just see myself as a musician these days. And that’s important now because every musician has to do everything they can to survive. I’m lucky enough to have been allowed to try a different avenue, and it’s worked out. Fortunately, my career trajectory has allowed me to not just be a guitar player. I’m not sure where I’d be if it didn’t happen that way.”

You and Danny appeared at Coachella recently. Is that something you plan to continue?

“Coachella was wonderful. We did it again at the Hollywood Bowl last Halloween, and I think we’re about to announce more appearances like that in San Diego and Irvine, California. So yes, we’ll do that again. It’s such a joy to be a part of those shows because it involves all the music we’ve done.

“And that means I get to conduct a small orchestra on stage while doing the Batman, Edward Scissorhands and Simpsons scores. It’s a true encapsulation of our entire career. And then we do Dead Man’s Party at the end, which is special, too.”

The rest of us love playing together, and that’s why we’ve been doing the former members tribute thing... we are essentially paying tribute to ourselves

While you’ve recently come full circle with Strawberry Alarm Clock, Oingo Boingo remains dormant. Is a reunion in the cards?

“I think Danny has more or less said that a reunion will never happen. He’s just not interested. But the rest of us love playing together, and that’s why we’ve been doing the former members tribute thing. We play pretty often, and it’s all the members of Oingo Boingo except for Danny.

“We’ve been doing that for around 15 years, and we’re especially active around Halloween because that’s when interest in Boingo spikes… It’s interesting because it is a tribute band, but with original members, so we are essentially paying tribute to ourselves.”

Andrew Daly is an iced-coffee-addicted, oddball Telecaster-playing, alfredo pasta-loving journalist from Long Island, NY, who, in addition to being a contributing writer for Guitar World, scribes for Bass Player, Guitar Player, Guitarist, and MusicRadar. Andrew has interviewed favorites like Ace Frehley, Johnny Marr, Vito Bratta, Bruce Kulick, Joe Perry, Brad Whitford, Tom Morello, Rich Robinson, and Paul Stanley, while his all-time favorite (rhythm player), Keith Richards, continues to elude him.