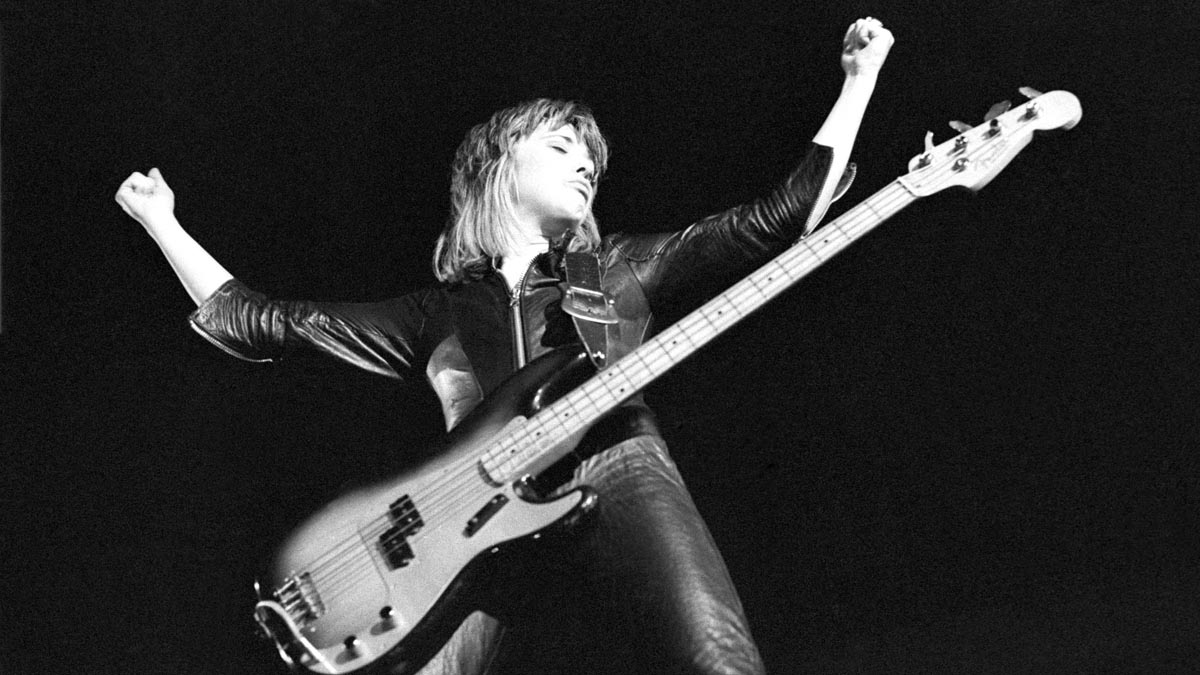

Suzi Quatro: ”I grew up in Detroit, so I was weaned on James Jamerson. He’s still the best. I very much take my style from him”

Kicking down boundaries, 50-million album sales, primetime TV star and awesome bassist... Suzy Q explains how she ended up owning the '70s

I don’t know about you, but if I make it to 70 years old, I plan to do a whole lot of sitting around and doing as little as possible. Of course, this is a shamefully lazy attitude, as evidenced by the phenomenal work ethic of Suzi Quatro, four months into her eighth decade as you read this – and busier than ever.

In 2020, she’s recorded an internet bass series, worked on a forthcoming biopic, promoted last year’s Suzi Q documentary, and written not one but two albums’ worth of songs.

“This is what I’ve done my whole life,” she tells BP. “When things get tough, I create. When my first marriage was going bad, I wrote a musical. Creativity, that’s what saves me every time, so I’ve been non-stop this year. I had something like 85 or 90 shows booked, even busier than last year, and of course they’re all postponed.

I don’t do the bullshit compliments – that’s not me

“As soon as we found ourselves in this situation, I built a studio out the back, and I said to my son ‘The option has been taken up by [record company] SPV for the next album, so now that we can’t play live, we’re going to write this album’ and that’s what we did. We wrote songs every single day, and now we’re recording it. It’s going fantastic. I’ve also released a coffee table-sized lyric book called Through My Words, and I’m working on two more books.”

Suzi Q, last year’s documentary about Quatro’s life and career, offered an insight into her character that was refreshingly free of any sycophancy, unlike so many similar productions. “You should watch it,” she advises. “It’s gone ballistic around the world. In America it was number two in the TV charts, with rave reviews, because it’s warts and all. It really shows what kind of person I am. I don’t do the bullshit compliments – that’s not me.”

Last time we visited Quatro in her country home north of London, we got to play her vintage Precision, a veritable warhorse from 1957 that hangs on the wall in a place of honour next to her fireplace. Does the old P appear on the new record?

“It does,” she nods, “but I was given a Rios bass guitar, so I’ve been using that as well as the old P-Bass. Rios are making a Suzi Quatro model, the Wild One, as well.” Appropriately for a Precision devotee, Quatro cites the master of that instrument as her primary influence. “I grew up in Detroit, so I was weaned on James Jamerson. He’s still the best. I very much take my style from him. I’m a cross between his style and boogie,” she says.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

I had James Jamerson as my example of what good bass playing could be. You really can’t wish for better than that

Were there any other female bassists at the time?

“Only Carol Kaye, who’s been around forever. There were other girl bands that I saw when I was weaned on music back in the States, but none that I ever heard that I took anything from myself. Why would I? I had James Jamerson as my example of what good bass playing could be. You really can’t wish for better than that. I was weaned on Motown music, so it’s in my DNA. He did his fancy licks, but he didn’t overplay.”

Has anyone come close to Jamerson’s standard since then? Quatro considers this before replying, “It’s hard to improve on what he did, because you’re talking perfection. The drums, the bass, and the tambourine were what made the Motown sound. That’s hard to beat. I will say that Flea is a terrific example of a bassist from a more modern era. He was able to take all the normal bass-lines and put his own little twist on it, which is not easy to do.”

As this issue of BP is dedicated to exploring the far-off world of the '70s – the decade when Quatro became a star – we ask her how life was for a fledgling rock star back then. In that decade, it seems to us, the wide world of music was there for the taking. This is some way off the mark, says Quatro.

“I don’t think everything was there for the taking at all. I actually think it was quite a difficult time,” she replies. “In the Sixties, every record company was throwing money at groups, and everybody was getting signed for big advances. That completely stopped, and also, artist contracts in the early '70s were notoriously bad. They were very one-sided in the record company’s favor, because those companies had been burned by a lot of the bands that they had signed.”

In fact, we were the last of the real musicians, as I’ve always said, who learned their craft through gigging. That doesn’t happen any more

Warming to her theme, she adds: “I didn’t find it a golden land of opportunity at all. In fact, it was a very confusing time in the business, because we’d come out of the hippie era and nobody quite knew what was going to happen next. At the same time, there was real talent, because you had all these musicians – like myself – who had learned their craft in the Sixties, in other words real musicians.

“In fact, we were the last of the real musicians, as I’ve always said, who learned their craft through gigging. That doesn’t happen any more, and it hasn’t happened since the '60s. The gigs just aren’t there to do it that way. So it was quite an unusual time. It felt as if the record companies were searching for a new style, to tell you the truth – like ‘Let’s see what comes to the surface’.”

Quatro herself didn’t so much come to the surface as smash right through it. Born in 1950 and a member of her sisters’ band the Pleasure Seekers by ’64, she moved to England at the age of 21 on the behest of the late producer Mickie Most.

“If you’re the right kind of person, you attract the right influence, and Mickie Most did give me guidance without taking over,” she recalls. “Those kinds of people – who can guide, and can mentor, and have the talent to star-spot and put you in the right situation – are very few and far between.

“A lot of people made it at the beginning of that era out of sheer luck, but people who only make it out of luck don’t usually stick around. You don’t hear about them later. The ones who have been mentored, and have the true artists’ skills, are around for life.”

Most knew the score, placing Quatro at front and center in her new band, ready for a sequence of hits from 1973 onward.

“When I first put the band together in early ’72, and we started to do college gigs, Mickie put us out on the circuit, got us an agent, and helped to buy equipment,” she remembers.

“I remember him saying to the rest of the band, and it’s quite funny when I think about it, ‘You guys are gonna have this amp and that amp, but Suzi has an Acoustic amp because it’s her band and she’s the star. She gets the best equipment because she’s the most important’. I thought, ‘Thanks a lot, Mickie – the band are really gonna love me now!’ But he was looking after me, he really was.”

It is popularly thought that rock music stepped up to arenas and stadiums in the early '70s because PA and amp technology had finally evolved to do the job in those large venues. Remember, even the Beatles had been inaudible at Shea Stadium in New York as recently as 1965. Is that correct?

“Yes, I think so. In the hippie era – when a lot of the bands were sadly lacking, in my opinion – the equipment wasn’t that good. There was a lot of feedback and so on, but when we got to the Seventies, equipment started to get better because rock music became more of a business.

Everything became more professional after the Sixties because music was no longer just a fun thing that some people could make a few dollars on

“People looked at the sound, they looked at the production, they looked at cleaning up after the '60s. Everything became more professional, because music was no longer just a fun thing that some people could make a few dollars on.”

How did that translate into Quatro’s bass gear, we ask? “Well, Mickie got me reflex cabinets for the Acoustic amp, because bass was always notoriously difficult to mic up on stage. It was always a trade-off between what you could hear yourself, and what the front of house could hear.

“There was always an argument about that, but the Acoustic was the first amp that had those reflex cabs, which threw the bass sound out. I had those from day one, even before I had a hit.”

It sounds as if Quatro avoided the fate of so many young musicians back then – being badly advised, exploited, or plain ripped off.

“Yeah. Luckily Mickie was a pretty straight guy. He gave us the kind of contract that was usual for that era. It wasn’t a great contract, but he didn’t cheat me and he gave me an advance. It was more geared to the American market, where I had a higher royalty because I was supposed to go back to the USA when I finished recording in England.

“Of course, I didn’t do that, so the lower royalty – which Mickie thought he was doing as a favor – worked out against me. We renegotiated that when my contract was up, though, and he always paid me what I was owed. The going rate of the day wasn’t great, like I said, but it was what the going rate was. If you look in the history books, you’ll see that the '70s were notorious for very low royalty rates.”

Our rose-tinted view of the '70s is getting less rosy by the second. Have times improved for artists since then? “Yes, I think so. Nowadays artists record their own albums and lease them out, which puts you in control of that album, and it also means that the rights come back to you. I own my last five albums, which is great. In the old days, artists didn’t have that.”

Does Quatro regard herself as an innovator in bass, we wonder? “I do, and in fact I can prove it with a story that I’m going to tell you,” she says. “I broke my left arm in 2012, and I had a tour booked, so rather than let the promoter down, I took a bass player out with the band. He played most of the set, and I just grabbed the bass for two or three numbers.

“I would die of agony while I was doing this, and this bassist said to me once ‘Oh my God. Even with your bad arm, it’s still a totally different sound. It’s the bass!’ That was how he described it, and for that reason I think I bring my own distinct playing to the instrument. I won’t have another bassist on any of my tracks; my bass playing and my singing go hand in hand. The style is connected, for some reason.

I was always going to be a bass player who could play and sing lead vocals. I never thought of it as difficult

“People always ask me how I sing and play at the same time,” she adds. “The truth is I don’t think about it. It just came naturally, although I think it helped that I learned percussion first, because then you’re thinking about moving your hands and feet separately. The same is true of piano. I do typing and shorthand too, and it all links together. I was always going to be a bass player who could play and sing lead vocals. I never even paused to think on that subject. I never thought of it as difficult, and I didn’t see why everybody kept saying that it was.”

On a recording session, is Quatro good at taking direction about her bass parts from producers or fellow musicians?

“Probably not, ha ha! I do take it, but I have to respect the person who’s giving it. Sometimes I can get carried away, and people have to say ‘Suzi, can you calm it down a little?’ I have been known to do that. I’ve had producers say to me ‘Can you play like a bass player?’, by which they mean, like a studio bass player. In that situation I’ll take it down a bit, yes. But I’ve always been stubborn. I know who I am.”

No matter what else was happening in the world, I stuck to being me. This is why I’ve lasted, because I’m not manufactured – I’m who I am

She muses: “I’ve always had more of a tomboy in me than anything else. I was never gonna be one of those frilly girl singers. It just wasn’t who I was. No matter what else was happening in the world, I stuck to being me. This is why I’ve lasted, because I’m not manufactured – I’m who I am. My own longevity is because I’ve stuck to me. I’ve not compromised who I am, and I won’t. I just won’t do it. I’d rather not be successful than not be who I am, and that’s the truth.”

Talking of the truth, Quatro is currently working on a biopic. “It’s the movie of my life, which is going ahead in response to the documentary doing so well. I’m very hands-on with the film – because I want the truth and nothing but the truth.”

So who’s playing the title role?

“A few names have been mentioned. Miley Cyrus has been mentioned more than once. She’s terrific, because she’s got the swagger. Everybody seems to like her. Billie Eilish has been mentioned too. I fancy Scarlett Johanssen for it, myself. I can see that because there’s an element of me in her.”

The film industry is even worse than the music business when it comes to liars and frauds. How is Quatro finding that world? “I deal with them the same way that I deal with everybody. I accept no bullshit!”

- The Suzi Q documentary is out now on DVD and digital.

Joel McIver was the Editor of Bass Player magazine from 2018 to 2022, having spent six years before that editing Bass Guitar magazine. A journalist with 25 years' experience in the music field, he's also the author of 35 books, a couple of bestsellers among them. He regularly appears on podcasts, radio and TV.