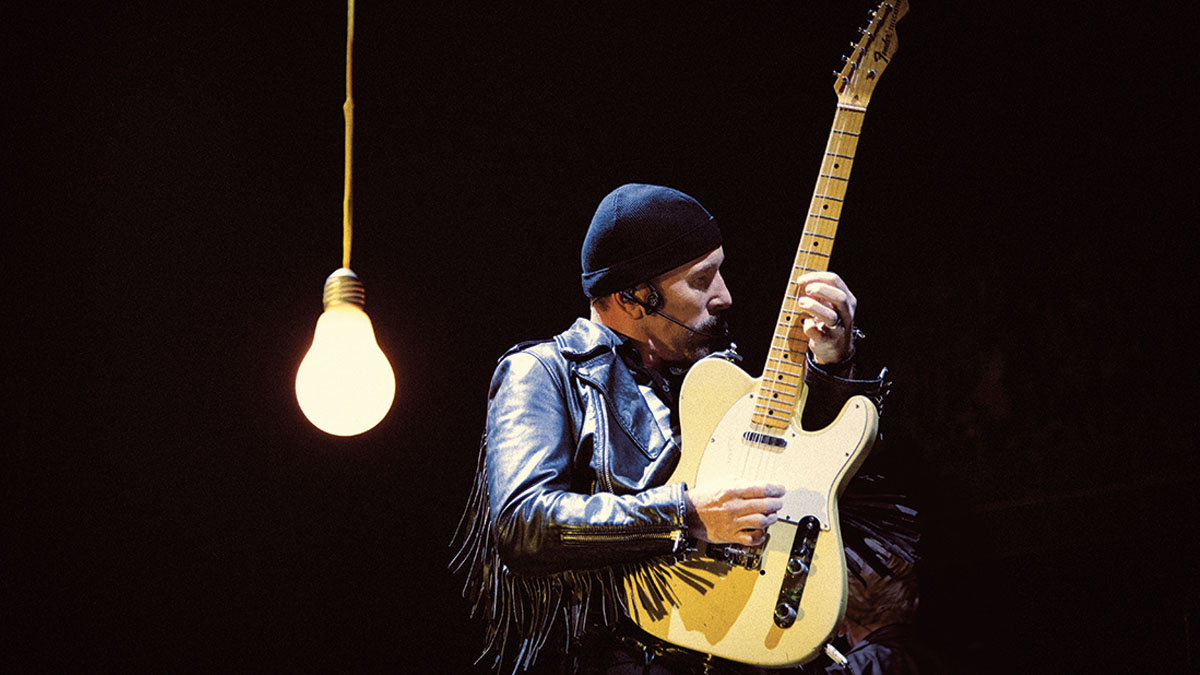

The Edge: “Digital delay was a way for me to add coloration, dimension, additional rhythm and a certain machine-age quality”

In this exclusive interview, U2's trailblazing sonic architect recalls how 1981’s October and 1991’s Achtung Baby helped the band forge and refine their identity

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Ever since joined the band that would become U2 – right around 45 years ago – guitarist the Edge has sought to be economical in his compositional choices. Every note he plays has a purpose and is dictated by whatever the song calls for.

“I like musical themes that create the biggest impact with the least effort, whether it’s [English composer Edward] Elgar or the Velvet Underground,” he says. “To my ears, economy is elegant.”

The Edge has used his unexpected, pandemic-influenced time off the road to reaffirm that belief and keep his skills sharp. He’s worked on new music and continues to work on his composing skills.

He utilizes guitar as well as keyboards and piano in an effort to “brush up on my understanding and ability to use some of these digital recording systems. These days, your laptop becomes a recording studio, so it’s been very liberating, in a way, to be able to develop music on my computer at home,” he says. “It’s been fun to really get into that.”

And then there’s his recent fascination with digital delay. “Digital delay for me was a way to add coloration, dimension, additional rhythm and a certain machine-age quality,” he says. “I know more about the mathematics these days, but it’s always about the part and the treatment evolving in tandem. It’s an instinctive and playful process. I never ‘use’ effects.”

No matter how elaborate his guitars and gear have gotten over the years, let alone the level of stardom the band has reached, the Edge hasn’t forgotten the blood, sweat and tears the band has shed over the decades – and the unbridled joy of creating music.

With the band’s 1981 album, October, turning 40 and their 1991 album, Achtung Baby, celebrating its 30th anniversary in 2021, it’s something that’s been on his mind of late. He hasn’t forgotten the lessons he learned making those albums – and the band members’ journeys discovering and refining what U2 is. While a lot has changed since those albums were released, much of what was learned on those albums still shows up in the band’s music.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“We are continuing our exploration of melodic essence,” he says. “It’s where all other aesthetic considerations fall away, and you can get to something truly timeless.”

In this exclusive interview, the Edge reflects on creating October and Achtung Baby – and how those transitional albums helped U2 find and refine their identity.

The creation of October was a real test for the band – and for you personally. What was that search for direction like, and how did you and the band channel that into the music?

“We were coming off an extremely busy period and ran slap bang into the cliché of all clichés when it comes to new songs: you have six years to write your first album – and then six weeks to write your second album. We came off the road and knew we wanted to follow up the Boy album as quickly as possible, but we really hadn’t managed to write much on the road.

“Bono had got some early lyric ideas on the go, and then he lost his briefcase – or his briefcase was stolen from the dressing room. We never figured out where or how he lost it, but he lost it. So we ended up back in Dublin, kind of exhausted, spent and knowing there was a huge herculean effort required to come up with songs for this follow-up record.

“Luckily enough, we persuaded Steve Lillywhite to produce. And I think, really, he saved our asses in some ways, because Steve is so practical and so positive. We kind of fessed up and said, ‘Steve, look, we’ve got a few sketches, but that’s kind of it. A few guitar riffs, basically. A few ideas for songs rather than even the beginnings of songs.’ So we went into the studio with Steve, and he said, ‘Come on, let’s just start with what you have.’

“We would literally go in, and I would work with Larry [Mullen Jr., U2 drummer] sometimes, or sometimes Adam [Clayton, U2 bassist] and Larry. We just laid down a bunch of these early drafts of compositions and slowly started to try and weld them together into cohesive tracks.

“And Bono really came into his own, I think, improvising on the microphone on that session. Thankfully we had a song called Gloria, which we were pretty happy about, and that turned out to be the sort of lead track. But a lot of that record is really written in the studio in a very experimental state of mind. And it was our first entry into what became a kind of important creative strategy for us over the years, which is turning the recording studio into a songwriting tool.”

I always play 100 percent better if I have a sound I’m excited by and that I find unusual and novel

How did you meet the challenge of working with such rough ideas?

“I think it would be fair to say all we had at the start were some guitar riffs. I Threw a Brick Through a Window, Gloria... I’m trying to think of the other ones. I Fall Down was probably written on piano, because at that point we had an electric piano that I used to use live. So, really, it was about composing music that felt like it could support a song, which I know is a strange thing, but having just come off the road, our instincts were fairly well honed for what was potent music.

“And then it sort of put Bono in the hot seat. He’s like, “Okay, we’ve got this track now – what are you going to do on it? What are you going to sing on it?” Which is really not the way songs are written. I mean, the best way to write a song is, you start with the chords and melody, and you build the arrangement. We were doing the exact opposite.

“We were building an arrangement that didn’t have a song and relying on our singer’s great melodic instincts to find a way into it vocally. From a guitar-sound point of view, back in those days, almost to the point where it was a freedom, we had limited amounts of guitars and equipment.”

“We really did specialize. I spent a lot of time homing in the guitar sounds, getting the treatments on the guitar as I wanted them. And all the effects, all the echoes, everything was put through the amplifier. There was no outboard; well, there’s very little outboard treatment of the guitar sound. So it was all mono reverbs, mono echoes and distortions through the amp.

“And in some ways the beauty of that, of course, is that you’re making your decision right there, and then at the beginning of the process, and you kind of get inspired by the sounds you’re creating. I certainly, as a guitar player, always play 100 percent better if I have a sound I’m excited by and that I find unusual and novel, and a kind of an entry into some other opportunity with a guitar.

“So, for instance, the guitar parts in Gloria, those ideas are born from the sound I created with that echo, that slapback echo. One of the bands I definitely was influenced by for that song was a band called the Associates. I loved what they were doing with their arrangements. But it was pretty simple stuff.”

What guitars did you use on the album? How did they impact the songs?

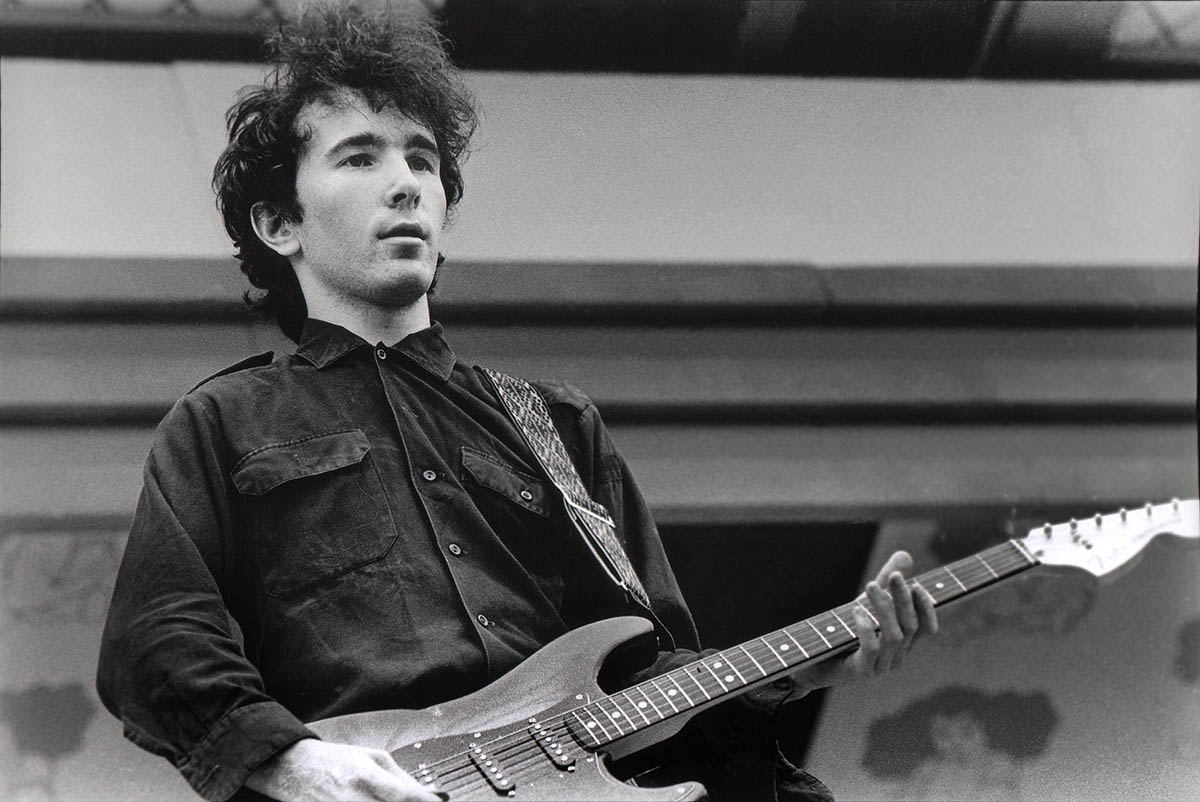

“My first professional standard guitar as a member of U2 was a Gibson Explorer, which I bought when I was 17. And that was my guitar. And I remember while making Boy, the first album, Steve Lillywhite said, ‘Have you got another guitar [so] we could try some sort of overdubs with a different tone?’ And I went, ‘Sorry, can’t help you. We don’t have another guitar.’

“We had one electric guitar in the band, one electric bass and one drum kit. That’s how stripped back it was. By the time we made our second record, I had bought a Fender Strat, but I wasn’t so happy with the sound of the bridge pickup. I ended up swapping out that pickup for a more full-sounding pickup.

We had one electric guitar in the band, one electric bass and one drum kit. That’s how stripped back it was

“I actually went into a store in New York and said, ‘Look, I want it to sound more full; it’s too bright, it’s too shrill through my amplifier – and I’m not changing my amp. This is an amp I’m really wedded to. What can you suggest?’ It was a [DiMarzio] FS-1, I think, that they put in the Strat. And it made a big difference. That was the formula for so many years going forward. I ended up buying a second black Strat as a spare and made the same adjustment.

“So those are the main instruments – that and the [Yamaha] CP-70, and I think at that point I had just bought a lap steel. I was just so intrigued. I was in Gruhn Guitars [in Nashville], I think, and came upon this Art Deco lap steel, probably from the '30s or '20s. I’d never seen anything like it. It didn’t have pedals, obviously, but the whole technique was all about slide.

“And it really taught me. That was the first time I really got excited about slide guitar. That’s featured on a couple of tracks on October. Other than that, [there’s] acoustic guitar, probably; I think we had one between us. We really were a pretty lean outfit in those days.”

What surprised you most during the recording process?

“Steve’s a great producer to experiment with sound, but within – obviously – the constraints of the band’s sound. We had a lot of fun with sort of Irish influences because we were going around Europe, and we had a very tight set from the Boy album. So it was a very European year we had spent prior to coming back.

“I think something about coming back to Ireland at the end of it, we felt that we saw Ireland in a new light, almost. It gave us this perspective. And we were like, wow, there’s a uniqueness here. Something you really don’t find anywhere else in terms of sort of traditional Irish music vernacular. On the October album we started experimenting with Uilleann pipes.

“We brought in an Uilleann pipe player – that’s the Irish version of bagpipes, but you don’t actually blow into the bag, you use your elbow. And so, Tomorrow was our first real attempt to reference our Irish tradition of music. That was a real thrill. And then October, the piano track, that was the first time we’d really done something that was more orchestral and less out of the garage band/punk-rock, post-punk rock idiom.

“We were playing around with the difference, sort of composing ideas, and I wrote that on piano at home. And then again, it was fun with Steve to find ways to layer the sound and give it other dimensions. Gloria and October are the ones we probably played live more than anything else from this record. They’re the ones that have stood the test of time.”

Do you think playing piano – and dabbling in other instruments – makes you a better guitar player?

“Not really a better guitar player, but I think it all goes toward making me a better composer and songwriter.”

October often gets overlooked in the scope of the band’s catalog. How do you feel about it gaining some appreciation over the years, especially from guitarists?

“I think October is a great testimony to the value of touring. We are so much more tight as a band having toured much of the previous year compared to the previous album. It’s a remarkably coherent album. We had a very limited palette, so we had to be inventive.

“Gloria is such a weird and beautiful song. It has some of the most unique guitar playing on a U2 record. We borrowed a Fender 12-string for the solos on I Fall Down and Tomorrow. Dueling solos with Irish uilleann ‘elbow’ pipes was a real musical experience. Vinnie Kilduff [who played the Uilleann pipes on the album] was amazing.”

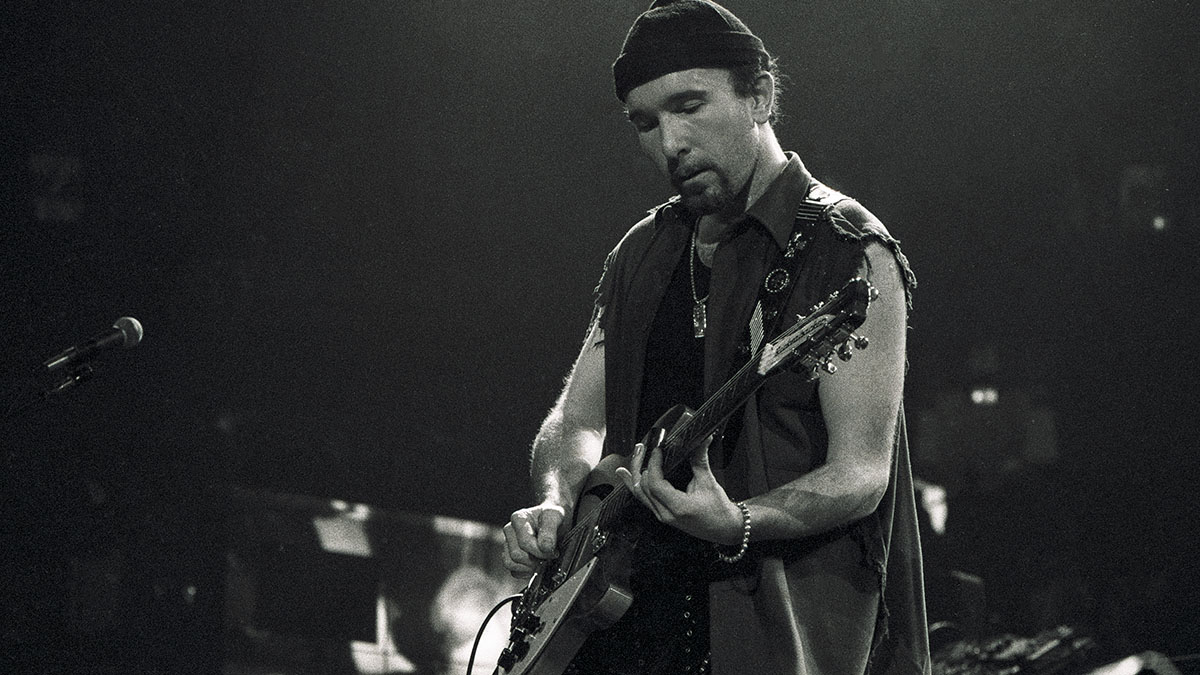

Achtung Baby was also a transitional album, but in a different way. The band sought to incorporate more influences and sounds. Why was it important to mix things up, and how did you tackle that challenge?

“I think our main creative axiom early on was to innovate, and to not sound like other acts, although we inevitably were part of a movement of bands that were thinking in those ways. So there was some borrowing of thoughts. But the need to be different and do our own thing serves us very well.

“I think we all felt by the end of The Joshua Tree [1987] and Rattle and Hum [1988] that there was a sort of weight of expectation amongst U2 fans, and maybe within ourselves, that kind of sense that we had established a sound, a thing, and it started to feel restrictive. It started to feel like we were being forced to repeat ourselves, or at least that seemed like the logical thing for us to do.

“So we did the opposite. We doubled down, and really rolled the dice again on innovation and doing something very different and outside of our comfort zone. Assuming that, as we had done with October, when you really do put yourself in that sort of position where you don’t know what you’re up to, where you really have to use imagination and resourcefulness as your main kind of get-out-of-jail cards, that it will bring out of you unexpected things and bring you to unexpected places. That was the sort of spirit in which we went into the writing of that record.”

What were some of your biggest inspirations for the album?

“I was very inspired by the sonics that were going on in other more sort of subculture music forms. The industrial music scene was sort of really exciting at that time, and bands like KMFDM and the Young Gods were doing quite extreme-sounding recordings. I liked that as a jumping-off point.

“And then the other thing that was happening was this technological breakthrough that came through sampling, and first through hip-hop, and then through the back door and through the club scene of Manchester, into more guitar-based music, which was this advent of the use of drum loops and samples to inject a kind of more rhythmic quality to the work. So as we went into the songwriting, I felt this was definitely an area we could move into as a band and develop.”

How did you put those sounds into action?

“Put very simply, I just felt like U2 had the potential to swing in a way we hadn’t up to that point. And so, I think that was the first time I actually had my own recording studio. The first and only time, since I don’t these days, but that was a great freedom for me as well. I was able to use the studio again on my own as a rising tool, and using drum machines, mostly.

“I didn’t tend to sample myself because in the end I knew Larry would be playing the drums, so it was more a songwriting and a production tool. But from a guitar point of view, again, it was like I was on the hunt for sounds I’d never heard, that we’re going to be startling to the other members of the band, and our audience, because that, I found over the years, was always the inspiration that got people excited and got people focused.”

What were some examples of that?

“I had an array of different effects units we brought first to Berlin and then back to Dublin after the first sessions. The album was originally started in demo form in Dublin, in a little studio we always used around that time called STS.

“It was a wonderful, tiny little space in central Dublin. And the kind of ergonomics of it meant we were on top of each other the whole time. Ideas always seemed to come easily to us there. Surprisingly, we always came out of that little studio with the beginnings of something we knew we could build on.

“We did our week or two-week session in STS, and out of it came a bunch of very basic ideas, but nothing finished. And then I did a little more work at home, and then we went to Berlin. In Berlin we kind of would try out this combination of the ideas we’d worked up together at STS, plus some of the stuff I’d worked up at home.

“We had a little bit of a wobble in Berlin at first. We were there with just Danny Lanois. I think ‘Flood’ [Mark ‘Flood’ Ellis, engineer] would have been there, too. But our songs weren’t really taking flight in the way we had hoped they would. The room was huge at Hansa Studios in Berlin. It wasn’t an intimate space, so we didn’t have the benefit of that close proximity that we had in Dublin. We floundered for a while.”

How’d you overcome that challenge?

“I remember there was a clear division – Bono and Edge were pushing forward with these new thoughts and ideas, musically. Adam and Larry were, I guess, early on open, and then as things didn’t start to fall into place, started to get very skeptical. So it was this kind of sense of, ‘Have we bitten off more than we can chew as a band? Are we trying to kind of make up a huge adjustment in a very short space of time, maybe beyond our capability to really reinvent ourselves and make such a hard turn where we are actually in danger of coming off on the bend?’”

“We persevered through difficult few weeks, and the breakthrough track, which sort of got us back on track was actually Mysterious Ways. I’d come up with this amazing guitar sound, which I laid on top of a very rhythmic track we’d worked up. I think it was, at that point, called Sick Puppy because it was such a rhythm thing. It initially was a drum machine, a bass and then this crazy guitar sound, but it wasn’t really a song.

“To be fair to Adam and Larry, it was kind of an idea for a song. So I was fighting very hard for it to make the record. They were looking at me like, what is this? It’s just a very funky verse, but that’s all it is. And so, I’m trying to come up with parts we could add to that verse to turn it into a full-fledged song.”

“There’s a couple of ideas that were tried [but] really didn’t work. And then I go off to another room and I work up a few different options, come back in the room, and I’m like, ‘Okay, here’s option A.’ And I play, I think, it was A minor, D, F, G, which is slightly strange sequence, but everyone, “Oh, that’s interesting.’ And then I said, ‘Option B is C, A minor, F, C. That’s my second.’ And Danny just went, ‘Hey, play those one after the other. Forget the other song, just play those two chord progressions.’

“So, I played one into the next. And he had heard something, and he was totally on it, which is why it’s very important to work with great producers. And everyone just went, ‘Yeah, that’s interesting.’ So, I think I just took the acoustic guitar in the room, and we started playing around with these two chord sequences, and everyone just went, 'Whoa, this is really, this has got gravitas. This has got – whatever it is we’re looking for – this has got that quality.'

“We played for about 10 or 15 minutes, and Bono started singing in the room with us, and effectively, almost in real time, the song One came together, compositionally. Lyrically it took a little while, but pretty quickly the idea of One emerged. It seemed almost like that song was written on a universal basis but was almost our own story. It was the song we needed as a band to keep us sort of together and on track and unified. It was a little autobiographical as much as it was an attempt to tap into some sort of universal truth.”

How did One develop into its final version?

“That song was acoustic guitar for a very long time because that was the sort of jumping-off point. But when Brian [Eno] came along a few weeks later to Berlin, he loved it. He loved so much of what we were doing, loved all the experimental rhythmic stuff, and thought we were really onto something fresh.

“But in true Brian [form], it’s ‘contrarian honest.’ He was like, ‘Well, the only song I really hate is One.’ And he said, “It’s not the song, but I think it’s just the wrong arrangement. It’s just, there’s no duality. It’s got this... It sounds exactly as you’d imagine a song like that would sound, should sound.’

“And to be fair, I mean, John Lennon was a little bit of an inspiration for the way I was hearing it. And you know, some of his classics are that simple. So it was back in Dublin, later, I had another chance to get into my studio and was able to put together the compositional idea for Until the End of the World, which was another important cornerstone.

“And so, we got back. All of us came back then after the break to work together in this little house called 'Dog Town' – that’s what we christened it. We occupied all the different rooms of the house in the basement and first floor. We made them into the control room, and other spaces became guitar booths, vocal booths and drum rooms.

“We set about really trying to define the sonic personality of these songs, some of which had a strong personality, like Mysterious Ways. But some really didn’t. So there’s a lot of experimenting and a lot of guitar sound creation. And if you put up those multi-tracks, there’s what made the final mix, but there are so many other things that didn’t make the cut. A lot of really extraordinary sounds, because that was certainly my thing at the time – to try and find completely different tones.

“There were a lot more sophisticated guitar effects available for the first time. I really found that appealing to just see what each one of these effects units could do. Again, everything through the amp, with a few more guitars onboard. I had a [Rickenbacker] 12-string. That’s what I used for Mysterious Ways, which I hope, maybe I didn’t say, but that was what that song Sick Puppy originally was. It became Mysterious Ways, but that was this funky sound.”

What were a few of your favorite experiences using those more sophisticated guitar effects that were available to you?

“It’s always about finding a sound that’s obviously inspiring – and quickly, so overly complicated units can sap inspiration. I did a bit of experimentation with harmonizers around that time, but nothing really went anywhere. I guess the sound I got for Mysterious Ways was a memorable discovery.

“We brought a prototype backing track to Berlin from a recording made in Dublin using drum machines. It was a very plain rhythmic foundation that we hoped to build up in layers, eventually to add real drums. That guitar sound and part from the Berlin sessions was the trigger for a lot of what transpired later on the track. By the time Larry played on it back in Dog Town, it was a very funky number.”

Did the Rickenbacker 12-string impact songs in new and interesting ways? Was it your main guitar?

“The Rickenbacker 12-string really came into its own while we were in Berlin, but I used other instruments quite a bit. There was a Les Paul Custom, which I donated to the first Music Rising charity auction. There was a beautiful Gretsch Country Club and my 1974 Strat. I think the Rick was useful in preventing me from going to any obvious places for guitar parts and sounds. It was instantly fresh and unusual, which helped me when I turned off the echo.”

- Achtung Baby (30th Anniversary Edition) and October (Remastered) are out now via Island Records.

Josh is a freelance journalist who has spent the past dozen or so years interviewing musicians for a variety of publications, including Guitar World, GRAMMY.com, SPIN, Chicago Sun-Times, MTV News, Rolling Stone and American Songwriter. He credits his father for getting him into music. He's been interested in discovering new bands ever since his father gave him a list of artists to look into. A favorite story his father told him is when he skipped a high school track meet to see Jimi Hendrix in concert. For his part, seeing one of his favorite guitarists – Mike Campbell – feet away from him during a Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers concert is a special moment he’ll always cherish.