The history of instrumental rock

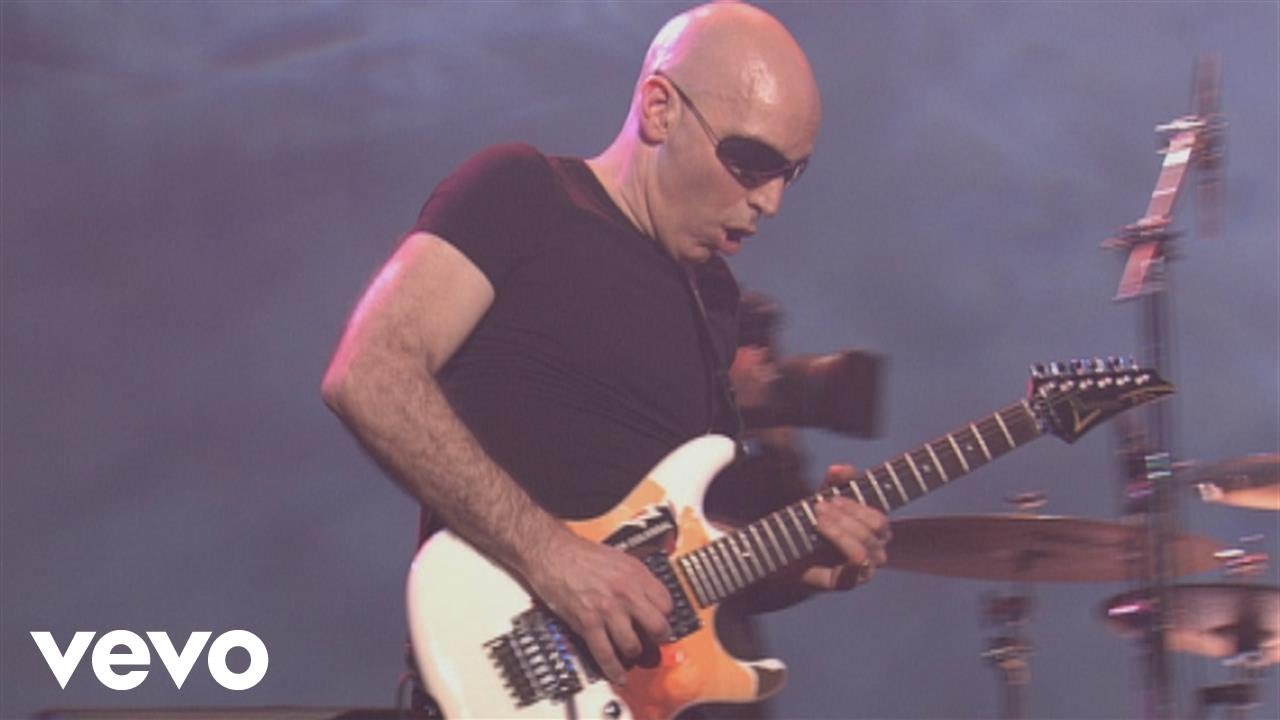

We look back at 60 years of the electric guitar-driven instrumental, from Link Wray and the Shadows to Dick Dale, Joe Satriani, Polyphia, Roopam Garg and beyond...

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

As a form of popular music, instrumental guitar-based rock first found popularity in the early '60s.

A few years before that, with early practitioners of the form such as Duane Eddy, with his simple low-string melodic lines such as Rebel Rouser, and Link Wray, who gave us the feedback-laden Rumble (which featured one of the first uses of the power chord), the genre quickly took hold with young guitarists everywhere.

Its rudimentary style made it easy for almost any guitarist to quickly fret a few chords, play some simple melodies, add an effect like reverb and presto! – a tune was born. Across the pond in England, the Shadows reigned as instrumental kings for the first few years of the '60s, beginning with their U.K. chart-topper Apache in 1960.

The Shadows’ lead guitarist, Hank Marvin, with his Fiesta Red Fender Strat (he was the first musician in England to own one) – resplendent with its maple fingerboard and gold-plated fittings, not to mention its owner’s unique use of the vibrato arm – would influence an entire generation of British guitarists that followed in his wake, from Eric Clapton and Jeff Beck to Pete Townshend and David Gilmour.

People who were in heavy metal bands or blues bands, for example, we’d bump into them at an airport or some function, and they’d come up to us and say, ‘Man, you’re the reason I play guitar!’

Hank Marvin

“In the early days when we first started having hits, we obviously didn’t appreciate that we would in any shape or form be influential,” Marvin says today. “It was a bit later, around 1962, when we started to realize that a lot of bands that were appearing in Britain and other countries were copying us.

“That’s when we realized we were having an influence. On one hand, we were a bit of a catalyst in getting people to pick up guitar, bass and drums, etc. On another, those who were already playing instruments, such as guitar, were turning around and wanting to play our style of music.

“That appreciation of the influence we had in the early Sixties was something we only came to understand more clearly as the years went by. People who were in heavy metal bands or blues bands, for example, we’d bump into them at an airport or some function, and they’d come up to us and say, ‘Man, you’re the reason I play guitar!’”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Meanwhile, the Shadows’ American “counterparts,” the Ventures – from Tacoma, Washington – hit the charts with their 1960 hit Walk, Don’t Run, which, in turn, ignited the inspirational fire for the burgeoning instrumental surf-rock scene. Repeatedly cited as the first surf-rock instrumental, Dick Dale and the Del-Tones’ 1961 tune Let’s Go Trippin’ officially ushered in the first wave of instrumental surf-rock’s halcyon days.

With its epicentre in Southern California, instro-surf soon spread across the country like wildfire. The Chantays’ Pipeline,’ the Surfaris’ Wipeout and Dale’s furious follow-up, Misirlou, further secured the genre’s strong foothold.

Many of the early surf instrumentals of the early Sixties weren’t just music without singing. They were creating music with other-worldly and non-linear spatial effects to create atmospheres

Dave Wronski

Hallmarks of instro-surf included sounds and tones that painted an aural picture of sun, surf and sand. Fender guitars were everywhere, especially the Strat, Jazzmaster and Jaguar, along with heaping helpings of spring reverb.

The Ventures later switched to Mosrite guitars, using them for the first time on their 1963 album The Ventures in Space, while Marvin played UK-made Burns guitars from 1964 to 1970.

“Many of the early surf instrumentals of the early Sixties weren’t just playing music without singing,” says Dave Wronski, guitarist with SoCal instro-surf rockers Slacktone. “They were, especially with the use of the Fender Reverb unit, creating music with other-worldly and non-linear spatial effects to create atmospheres, and/or sounds of nature, representations of wild ocean surf, volcanoes, car racing, etc.”

“The genre was incredibly diverse, with artists like Link Wray, Freddie King, Santo & Johnny, Dick Dale, the Ventures, Hank Marvin and others,” adds instrumental rock meister Joe Satriani. “They all showed the importance of melody over flash but never failed to impress with technical innovations. Not an easy feat in any genre! This approach built the foundation for future artists like myself.”

As the British Invasion began transforming the entire musical landscape in 1964, instro-surf’s popularity soon waned. Penetration by California combo the Pyramids would bookend the genre’s heyday.

Gone to ground, the instrumental continued to evolve in the hands of guitarists such as Jeff Beck, Peter Green, Clarence White, Danny Kirwan, Lonnie Mack and others who, although not primarily instrumental guitarists, featured instrumentals in their live and studio outings.

This endured throughout the '70s, when the Allman Brothers Band’s catchy, harmony-infused Jessica, Santana’s soulful Europa (Earth’s Cry Heaven’s Smile), Van Halen’s game-changing tapping opus Eruption and Jeff Beck’s jazz-fusion explorations on 1975’s Blow by Blow and 1976’s Wired expanded upon the instrumental template.

I don’t even know if I can take credit for writing Cliffs of Dover. It was just there for me one day. There are songs I have spent months writing, and I literally wrote this one in five minutes

Eric Johnson

When the '80s were in full swing, instrumental rock had morphed into a more virtuosic format. Gone was the simplicity of the early years where any guitarist, even a beginner, could pick his way through an instrumental.

Now, a much more advanced and technical approach was at the fore, propelling the genre forward and outward into unlimited and untapped possibilities. What do we mean? Just give Steve Vai’s The Attitude Song a quick spin.

Shrapnel Records, set up by young enterprising musician Mike Varney in 1980, became ground zero for the decade’s virtuosic instrumental guitar players.

By pushing the boundaries of the instrumental realm by the fusion of speed and classical elements mixed with hard rock and heavy metal styling, it birthed a whole new generation of shredding, neo-classical players.

Critically and commercially acclaimed, it ignited a second wave of popularity into the instrumental genre, courtesy of the likes of Marty Friedman, Yngwie Malmsteen and Vinnie Moore. Later, similarly styled guitarists such as Satriani and Vai would drive the genre back onto the charts.

Satriani in particular would be a huge part of popularizing shredding and bring instrumental rock right back into the mainstream – and to the masses.

His 1987 album, Surfing with the Alien, was a pièce de résistance built upon what had come before, yet it took it light years into the future, bucking all musical trends of the day. Peaking at Number 29 on Billboard’s Top 200 Album Chart, it affirmed that the new instrumental guitar hero of the time had finally arrived.

“I wanted Surfing to be a celebration of all my influences as well as a big step into the future of instrumental electric guitar,” Satriani says. “Its initial and continued success has validated my feeling that artists should do what they want – regardless of current trends – and stay true to their artistic goals.”

Of course, no overview of instrumental rock could fail to mention Cliffs of Dover, Eric Johnson’s super-catchy 1990 thrill ride, which – surprisingly – didn’t make the cut for his 1986 album, Tones, and was written pretty damn quickly.

When this new stuff came along, Joe Satriani and people like Steve Vai and things like that, I thought it was really exciting. It was a different way of playing guitar

Hank Marvin

“I don’t even know if I can take credit for writing Cliffs of Dover, ” Johnson said years ago. “It was just there for me one day. There are songs I have spent months writing, and I literally wrote this one in five minutes.

“The melody was there in one minute and the other parts came together in another four. I think a lot of the stuff just comes through us like that. It’s kind of a gift from a higher place that all of us are eligible for.”

“When this new stuff came along, Joe Satriani and people like Steve Vai and things like that, I thought it was really exciting,” Marvin adds. “It was a different way of playing guitar from the way I and other guys were playing.

“It was very technical, a lot of virtuoso playing going on there, and I guess it was just right for the time. A lot of music, in my experience, when it becomes successful, it’s because it’s right for the time, and probably the artist is right for the time too. Maybe five years earlier it wouldn’t have happened.

“Five years later it may not have happened either. I thought it was terrific, as it was good to see that instrumental guitar music was still being played by people like Joe, Steve, Eric and other guys like the Hellecasters’ John Jorgensen, Jerry Donahue and Will Ray.”

As one of Satriani’s early guitar students, Vai followed his former teacher’s footsteps with the release of his magnum opus, 1990’s Passion and Warfare, an album that expanded upon the formula and furthered the genre’s standing with the populace.

Following the lead set by Varney’s Shrapnel label, Vai would later venture forth on a similar route, co-founding the Favored Nations label with former Guitar Center owner Ray Scherr in 1999. But with grunge engulfing the musical landscape and transforming it forever, guitar-driven instrumental music again fell out of favor, and the few remnants that remained went underground.

Instrumental rock received a massive boost in 1994 when Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction featured Dale’s Misirlou in the film’s opening credits.

This newfound interest would influence many of the up-and-coming bands on the scene, such as Alabama’s Man or Astro-Man? and Nashville’s Los Straitjackets, both of whom fused the sound of early surf with a garage-y punk spirit.

If we don’t leave practice humming at least one of the guitar lines, it’s not going to survive. Melody becomes its own lyric, its own voice

Munaf Rayani

Los Straitjackets added an aesthetic ingredient as well to their live performances, with the wearing of Mexican Lucha libre wrestling masks.

While others such as Chicago outfit Tortoise, whose cocktail of jazz, electronica and dub influences, and Scottish combo Mogwai pushed the genre further along a more experimental route soon to be known as post-rock, a term coined by Mojo writer Simon Reynolds in 1994.

Post-Rock instrumental bands utilized the guitars to paint aural images where tonality, rhythms and textures took priority over riffs, melodies and solos. This approach had more in common with elements found in the cinematic film scores of the '60s, the early progressive sounds of bands such as Pink Floyd and the soundscapes of ambient music.

“Ennio Morricone, in a similar time frame, was using unusual sounds in his movie scores,” Wronski says. “That helped create imagery, alone, without the visual of the film.

“Pink Floyd’s atmospheric instrumental textures seem to be part of that lineage. Jimi Hendrix, with the instrumental portions of his songs, created – with his guitar – sonic atmospheres not heard before.

“Billy Cobham’s first solo album, Spectrum [1973], was an important instrumental album for guitar and drums. Jeff Beck, I think, was inspired by Spectrum to begin his instrumental contributions, beginning with Blow by Blow and Wired, two classics.”

New rhythms, new melodies, 10-string wizards… Every generation creates their own groove and tone. It’s inevitable and I welcome it

Joe Satriani

Post-rock continued flying the instrumental flag during the 2000s. Rising out of Austin, Explosions in the Sky adopted a three-guitar frontal attack to serve up lengthy progressive instrumental aural explorations that lent themselves perfectly for film and television soundtracks.

“Melody is everything,” Explosions guitarist Munaf Rayani told us in 2011. “If we don’t leave practice humming at least one of the guitar lines, it’s not going to survive. Melody becomes its own lyric, its own voice.”

Fellow Texans This Will Destroy You followed suit with atmospheric effects and layered soundscapes while Irish outfit God Is an Astronaut fused Krautrock, space-rock and electronics into the mix.

As this new decade dawns, the new kids on the block are pushing the boundaries of the genre to further extreme levels.

Texan combo Polyphia, based around the six-string pairing of Tim Henson and Scott LePage; Washington, D.C., three-piece Animals As Leaders, featuring the innovative playing of guitarist Tosin Abasi; and Boston-based progressive trio the Surrealist, led by guitarist Roopam Garg, are among the bands leading the charge.

They’re all creating highly innovative and otherworldly soundscapes, taking the Post-Rock sounds and completely dismantling them.

“The best music for me has always been music that affects my perception of the world,” Garg enthuses. “I treat compositions as if they’re lenses to look at the world through, with each lens unmasking a certain portion of reality. It’s analogous to watching a movie. As you view the film, the music can serve up to 90 percent of the emotional content within the frame.

Good film scores are able to bring out anxiety, hope or depression within the characters, without which the film would be devoid of human connection. Music plays such a truly vital role in the perception of the mind – you could overlay different music on the same movie scene and alter the narrative simply by the fact that you’ve changed the underlying score.

Too many bands just do the same things over and over. What’s the point? Be yourself. Be original. Otherwise, move out of the way

Tim Henson

In the same way, if you listen to a beautiful piece of music as you’re walking across a traffic intersection, you notice things in people’s expressions and mannerisms that would otherwise be overlooked without music. I absolutely love that.”

As Polyphia’s Tim Henson told us last year, “We definitely want to fuck shit up. If something’s been done before, we want to turn it upside-down and mess with it. Too many bands just do the same things over and over. What’s the point? Be yourself. Be original. Otherwise, move out of the way and let somebody else have at it.”

With their hunger to explore and a spirit of experimentation, guitarists such as Abasi and Garg are also eschewing the six-string guitar in favor of eight-string guitars.

“There’s a psychological shift to having access to more strings,” Garg says. “It alters your perception of what a guitar is. With full access to both the upper and lower registers, you’re able to approach composition in a more holistic way with one instrument. You also have more options with regard to different timbres. The same note will sound different on different strings simply by virtue of string thickness.”

Abasi has gone one step further, developing a new line of innovative guitar designs via his recently formed company, Abasi Concepts.

Garg is a recent convert – and an endorsee of Abasi’s guitars: “Tosin has created one of the best guitar designs in the world. I can’t say enough good things about their guitars, which they’ve named the Larada. I’m someone who focuses a lot less on specifications and more on how I feel when I play an instrument, and the Larada mysteriously just feels perfect in every way.”

I’m allowed to explore unorthodox sounds on the guitar that wouldn’t have a home anywhere else

Roopam Garg

While guitar-based music tends to be a primary source of inspiration for most guitarists, in Garg’s quest to approach the world of instrumentals in an innovative spirit, it is artists working in an ambient experimental format that inspire his guitar playing.

“Ambient music is more liberating as a composer,” he says. “There are no restrictions from rigid structures or instrumentation. You’re literally able to paint whatever you want on a blank canvas – anything goes. I’m allowed to explore unorthodox sounds on the guitar that wouldn’t have a home anywhere else.

“Other than ambient music, what kind of genre would call for the scratchy sounds of a broken lead cable, or an out-of-tune instrument? or the sounds of breathing, bleeding through the mic?

“These ‘imperfections’ are overlooked and even seen as blemishes in other, more sterile environments like progressive metal, where it seems like perfection is the end goal. There’s no room for error. But I love errors.

“These genres seek the perfect guitar tone, the perfect mix, the perfect guitar solo, and end up overlooking beauties underneath the cracks of the guitar that I wish to explore. I mostly listen to a lot of other ambient experiments artists like Nils Frahm, John Hopkins and Taylor Deupree, as well as film soundtracks.

“I don’t really pay attention to what other guitar players are doing nowadays. I don’t think I listen to any guitar-centered music any more, sadly. Except maybe Meshuggah and Animals As Leaders.”

For Wronski, it’s the challenge of working (mostly) within the confines of the original surf records – while not ignoring what came after – that drives his approach.

“[It’s about] theme, imagery and motion, coupled with a big, flattering (to the guitar and the melody) sound with depth and punch,” he says. “Right-hand dynamics are king, and the amp responds to the intensity of the touch, with the guitar not just acting as a trigger. What I think the original guys wanted to achieve is to make their guitar sound like an orchestra in one handful of guitar.”

The evolution of instrumental guitar music over the past 60 years has seen a gigantic leap forward for the form, and with the new players on the scene, its future looks even brighter.

What I think the original guys wanted to achieve is to make their guitar sound like an orchestra in one handful of guitar

Dave Wronski

28-year-old Australian maverick prog-rock guitarist Plini is just one of those new kids on the block who are gleefully propelling the genre onward. His head-turning sonic explorations have even caught the ear of Steve Vai, who declared, “When I saw Plini play, I felt that the future of exceptional guitar playing was secure.”

Plini’s self-released 2016 debut album, Handmade Cities, was also praised by Vai. Other at-least-mostly-instrumental names to watch out for include Sarah Longfield, Chon, This Patch of Sky, Yvette Young, Al Joseph, Tauk, Distant Dream, And So I Watch You from Afar, Angel Vivaldi, Standards, Hedras, Toska, Yasi Hofer, Deaf Scene and Jason Richardson.

...Also, Gretchen Menn, Sithu Aye, I Built the Sky, Unconditional Arms, David Maxim Micic and Mike Dawes. And let us not forget Julian Lage, Guthrie Govan, Johnny A., Nick Johnston, Misha Mansoor and – well, the point is the list is almost endless in 2020, which implies that the guitar-based instro-rock scene is quite robust, to say the very least.

“New rhythms, new melodies, 10-string wizards… Every generation creates their own groove and tone. It’s inevitable and I welcome it,” Satriani says. “It’s so cool to see so much innovation going on with the younger players.

“A few years ago I witnessed Animals As Leaders at a live charity event we were playing together and I was completely blown away with the magic they created with their original music and a whole new set of guitar techniques. It’s a great time for guitar, even if the pop charts don’t reflect it. There’s a lot of creativity going on behind the scenes right now.

“My new album, Shapeshifting is a big leap forward for me. I’ve taken some giant steps in how I approach composition and arrangement, and it’s paid off. I really love this album!”

Joe Matera is an Australian guitarist and music journalist who has spent the past two decades interviewing a who's who of the rock and metal world and written for Guitar World, Total Guitar, Rolling Stone, Goldmine, Sound On Sound, Classic Rock, Metal Hammer and many others. He is also a recording and performing musician and solo artist who has toured Europe on a regular basis and released several well-received albums including instrumental guitar rock outings through various European labels. Roxy Music's Phil Manzanera has called him, "... a great guitarist who knows what an electric guitar should sound like and plays a fluid pleasing style of rock." He's the author of Backstage Pass: The Grit and the Glamour.