The inside story of The Beatles' turbulent break-up - and what came next

50 years on, we dig deep into the unraveling of the most commercially successful band of all time, and the subsequent solo careers of John Lennon, Paul McCartney and George Harrison

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

For Beatles fans, 1970 was a particularly heavy year - one in which we watched one of our most beloved bands fall apart, and witnessed the rebirth of each Beatle as a solo artist.

The chronology itself is crazy. A slew of Beatles-related albums were released in the space of that single year, starting with Ringo Starr’s solo debut, Sentimental Journey, in March. Then came Paul McCartney’s self-titled debut LP in April, along with a press release making it more or less clear that the Beatles were finished.

The stage was set for the May release of the Beatles’ final album, though penultimate rerecording, Let It Be: a troubled and uneven set of tracks culled from sessions in 1969 that hadn’t gone well.

It was the soundtrack album for a film of the same title, which chronicled the tragedy of a great band falling apart, while also giving us a last look at that Beatles magic, resplendent even in dysfunction.

Ringo was quickly back in the fray with a country record, Beau-coups of Blues, released in September and drawing on the talents of some of Nashville’s greatest guitarists and other session players.

More guitar grandeur came in November when George Harrison’s epic triple album, All Things Must Pass, came out; and the year closed with John Lennon’s stunning solo debut album, John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band, a stark swansong to the '60s that also charted a bold course forward into Lennon’s solo career.

As the Beatles faced the challenges and excitement of new solo careers, Harrison, Lennon and McCartney would each build on the groundbreaking guitar legacy they had forged together over the course of the Beatles’ career.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

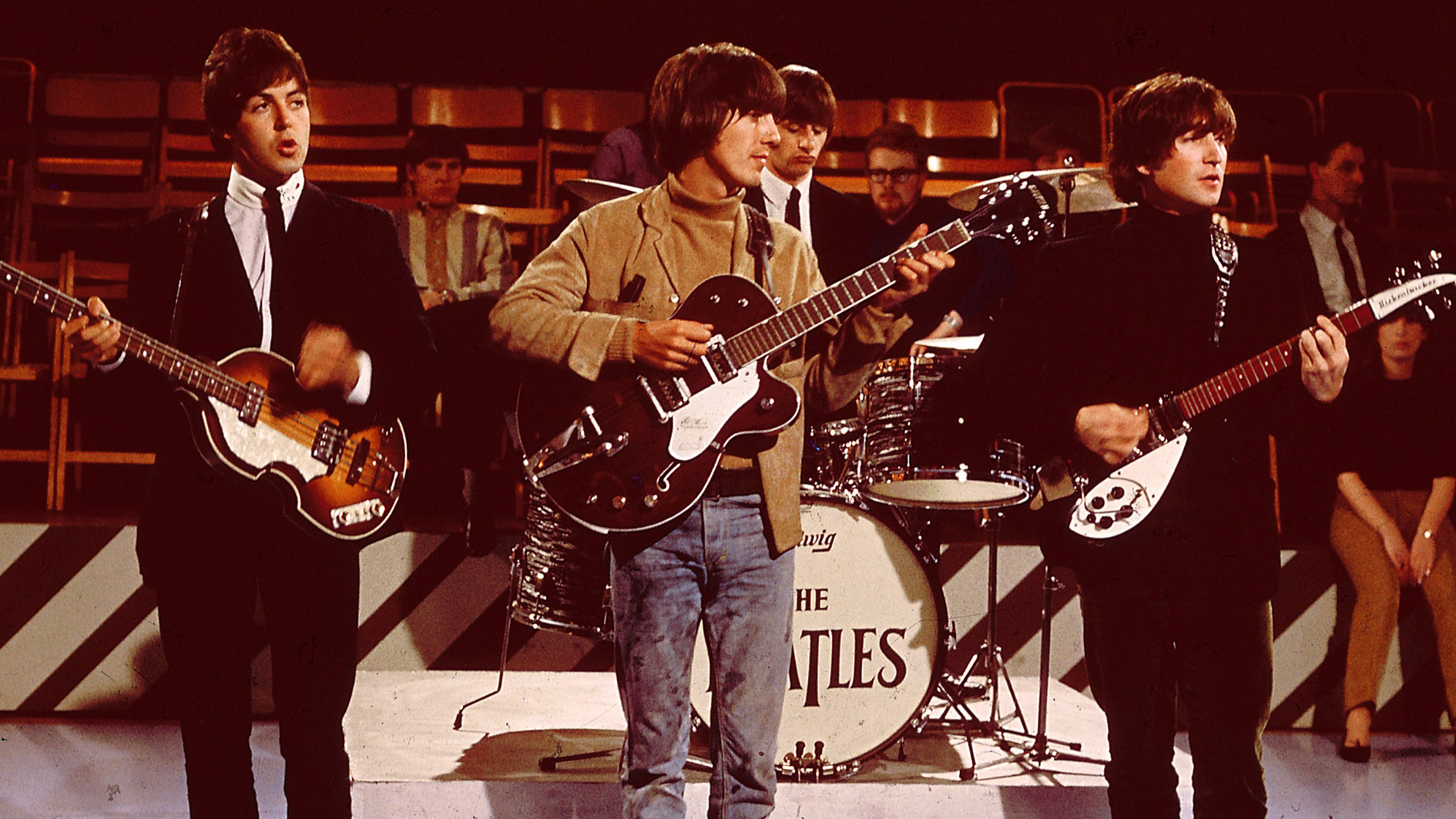

So many of their most revolutionary rock guitar innovations were collectively wrought. I Feel Fine from 1964 became the first rock record to feature the creative deployment of guitar feedback, when the A string on McCartney’s legendary 1963 Hofner 500/1 violin bass triggered a trans-ductive loop between Lennon’s Gibson J-150 E electro-acoustic guitar and his Vox amp.

The gloriously multi-tracked guitar harmonies on 1966’s And Your Bird Can Sing from Revolver were a collective effort between Paul and George. And to create the pioneering backwards guitar solo on I’m Only Sleeping from the same album, Harrison spent hours with engineers Geoff Emerick and Phil McDonald. Then George and Paul worked extensively with the engineers on the harmonized backwards outro.

Feedback and backwards tape tracks - not to mention a whole revolutionary take on the role of the electric guitar in rock music - would become integral to the work of Jimi Hendrix, Pete Townshend, Jeff Beck and many other greats. But it all originated with the Beatles.

And while 1970 was the year it all came tumbling down and spilling out in every direction, the demise of the Beatles and the emergence of Lennon, McCartney, Harrison and Starr as solo artists was a process that unfolded over a period of several years.

The 1967 death of the Beatles’ longtime manager Brian Epstein set the wheels in motion. But, while management issues are what would finally split up the Beatles, it was also, ultimately, a simple matter of four highly gifted young men growing up and growing apart from one another.

Let It Be - bad vibes beset The Beatles

The Beatles had little love for Let It Be. John Lennon called it “the shittiest load of badly recorded shit with a lousy feeling to it ever.” The disc stuck in Paul McCartney’s craw for decades, to the point where, in 2003, he put out his own “revenge” remix and digital remastering of the album, Let it Be… Naked.

George Harrison spent years blocking the DVD release of the Let It Be movie. (As we speak, Lord of the Rings director Peter Jackson is working on a documentary based on unused footage from the recording of Let It Be; it’s expected to be released this year in time for the original film’s 50th anniversary.)

It had all begun in McCartney’s desperation to keep the Beatles together as the whole thing fell apart around him. He floated the idea of a concert film that would capture what was generally hoped would be the Beatles’ first live performance since retiring from touring in 1966 to concentrate on their recording.

Let It Be was the shittiest load of badly recorded shit with a lousy feeling to it ever

John Lennon

The idea was doomed from the start. The sessions got underway just three months after the Beatles wrapped up 1968’s The Beatles, AKA the White Album. Lennon, McCartney and Harrison pretty much put all their best songs into that massive double-disc project. So they didn’t have a lot of new material to record.

“The only thing we haven’t got for every song is… the song,” McCartney mused at one point. Paul is really the only one who came in prepared with a few A-list songs ready to commit to tape. These would become the Beatles’ final hits, Let It Be, Get Back and The Long and Winding Road. Lennon’s mind and heart were elsewhere - with the new love of his life, Yoko Ono, and the cutting-edge work they were doing with music, film and performance art.

His songwriting contributions to the Let It Be sessions tend to be more fragmented and free-associative. Dig It, for example. Is it really a song? It’s well named, as the group was clearly digging around for pretty much anything to put on the record. The last-minute addition of Across the Universe (originally recorded in ’68), ups the album’s quotient of great Lennon songs, although John hated that recording as well.

Harrison’s head was elsewhere too. He was off gigging with Eric Clapton and hanging out with Bob Dylan. His own tepid 12-bar contribution to Let It Be, For You Blue, isn’t one of his best efforts either. And Ringo had his eye on a movie career.

Making the White Album had been tense enough for them. Ringo had stormed out of Abbey Road Studios during those lengthy sessions, only to return a few weeks later. George became the next Beatle to walk, during Let It Be rehearsals at Twickenham Film Studios in January 1969. His angry departure was captured on film by director Michael Lindsay-Hogg.

Harrison only returned on the condition that the live concert part of McCartney’s original plan would be scrapped. But things only got more tense once the Beatles adjourned to their new recording studio in the basement of Apple HQ in London’s Savile Row.

Lennon had told the Beatles’ longtime producer that this time he wanted none of Martin’s usual “production nonsense"

They had commissioned one Alexis Mardas - AKA “Magic Alex” - to design and build the studio. He sold them on a bunch of new technologies that only existed in his imagination. An invisible force field around Ringo’s drums was to control microphone leakage onto any of 72 tracks, back when 16-track was only just arriving on Planet Earth.

Needless to say, little of it worked. A hasty request was sent to EMI’s Abbey Road studio for supplementary equipment. Faced with challenges like these, it would have been nice to have George Martin around. But after years of pushing the musical envelope together, Lennon had told the Beatles’ longtime producer that this time he wanted none of Martin’s usual “production nonsense.”

It was a perfect recipe for disaster. Much credit for getting some solid tracks down to tape is due to the soon-to-be-legendary Glynn Johns - hired strictly as a balance engineer for this project - and Alan Parsons, who would go on to engineer Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of the Moon and garner considerable radio airplay with his own Alan Parsons Project.

Cameras captured some of the last live-in-the-studio guitar interplay between Harrison, Lennon and McCartney. Lennon played the country-flavored leads on Get Back on his ’65 Epiphone Casino, while Harrison played rhythm on a rosewood-body Telecaster he’d recently received from Fender. The same guitar through a Leslie 147 cabinet gifted to George by Eric Clapton was used for one of the two lyrical solos on Let It Be.

He later cut another solo with his “Lucy” Gibson Les Paul, another gift from Clapton, through the same Leslie. The Les Paul solo is heard on the 45 rpm single mix of Let it Be, produced by George Martin. The Telecaster solo is heard on the album version, mixed by Phil Spector.

Quite a lot of bad blood, animosity and litigation lay behind this tale of two producers. Maybe it was for the best that Ringo was due on the set of his next feature film, The Magic Christian, which would be released in 1969. But before the sessions wrapped, Lindsay-Hogg’s film crew were able to capture the Beatles’ final live performance on the roof of Apple HQ.

Feeling this was no way for the band to falter, George Martin was told that they were headed back into Abbey Road, with him back in charge, to record one last “proper” Beatles studio album.

The result was their glorious swansong disc, Abbey Road. Despite growing hostilities, all four Beatles made a heroic effort and created one of their greatest albums. But although there was talk of further releases, at a band meeting on September 20, 1969, Lennon announced that he wanted a “divorce” from the Beatles.

It’s a myth that there was an outstanding contractual commitment to United Artists for one more Beatles movie - the band’s Yellow Submarine cameo had solved that problem. Nevertheless, it was decided to edit together a feature film from the footage Lindsay-Hogg had shot of the difficult early ’69 sessions at Apple, and to assemble the audio tracks from those sessions into a soundtrack album.

To salvage the audio tracks, Lennon and Harrison, in concert with manager Allen Klein, enlisted legendary American record producer Phil Spector to do some emergency editing, overdubbing and remixing.

McCartney hated the whole thing. He hated the idea that Allen Klein had been involved in Spector’s hiring. Klein was the true straw that broke the collective back of the Beatles. Lennon, Harrison and Starr wanted the New York businessman to take over as the Beatles’ manager. McCartney wanted the group to sign with Eastman and Eastman, the law firm headed by the father and brother of his new bride, rock photographer Linda Eastman.

While fans could still enjoy watching their idols perform, there's also the hopeless sense of sadness that’s felt whenever you witness people you love quarreling and being miserable

Perhaps even more than Klein, McCartney hated the lavish orchestral and choral arrangement that Spector added to “The Long and Winding Road.” George Martin and Glynn Johns backed McCartney in denouncing Spector’s work.

When the Let It Be film was first released, in May 1970, it was viewed with a certain amount of sadness by the Beatles’ original generation of fans. Beatles movies had always been joyous occasions. And while fans could still enjoy watching their idols perform, there was also the hopeless sense of sadness that’s felt whenever you witness people you love quarreling and being miserable.

For many people, there are two moments that seem like the final farewell from the Beatles. One is the Apple rooftop concert at the conclusion of the Let It Be movie - the four Beatles, plus Billy Preston, laying it down live one last time above the streets of London. The other is the guitar jam on The End, which closes Abbey Road.

The Fab Four’s three guitar men trade two-bar licks - Paul, then George, then John - three times around. The spirit of the Beatles’ early days in Liverpool and Hamburg was in the room. In different ways, some of that spirit would endure in the solo work of the four Beatles.

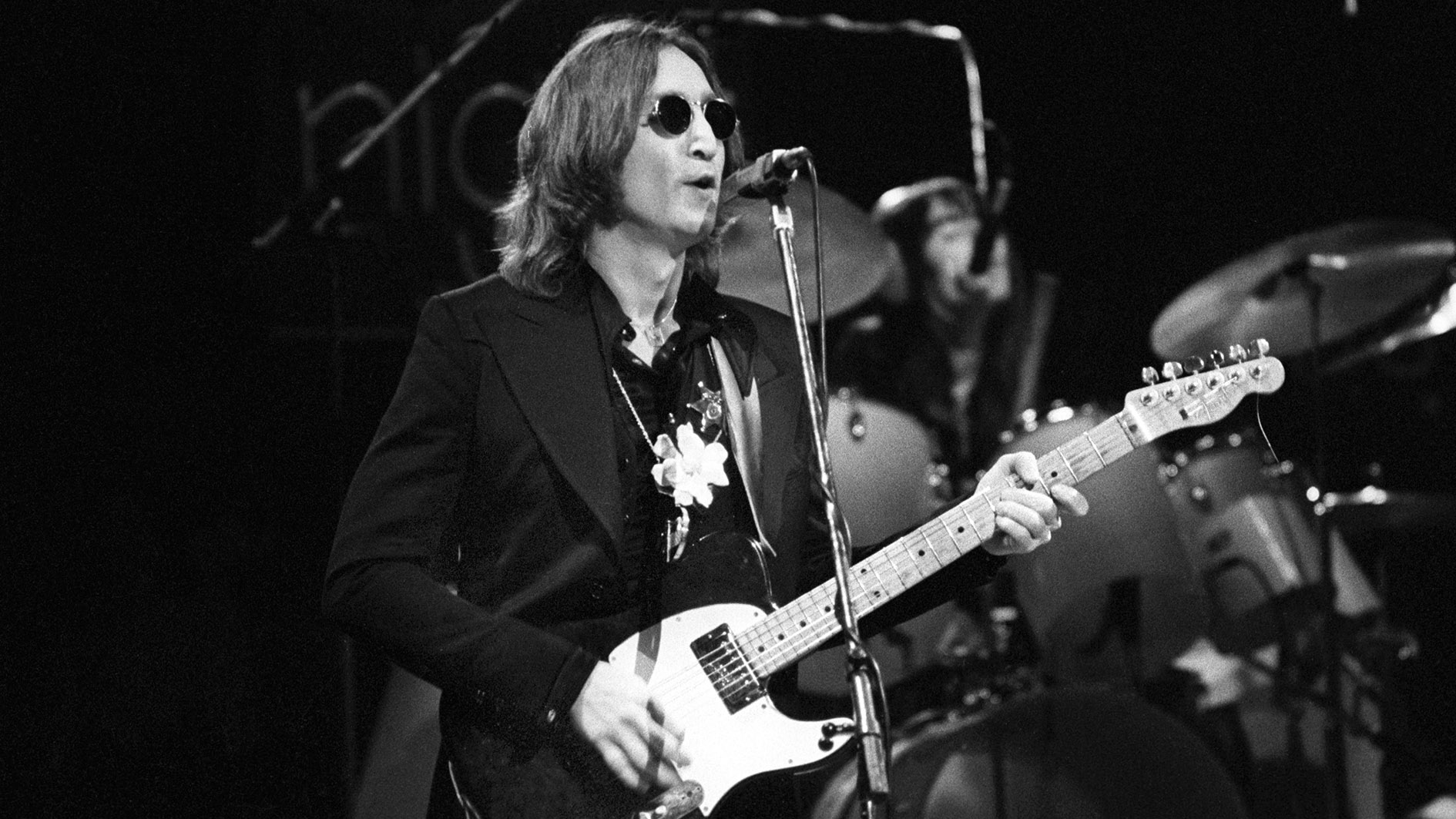

John Lennon - the raw essence of rock guitar

It all starts with Lennon, of course - fronting the Quarrymen, strumming a cheap Gallotone Champion acoustic guitar, playing banjo chords in a tuning his mother had taught him. McCartney showed Lennon standard tuning, and the repertoire of the Quarrymen progressed from folksy skiffle to hard-driving rock and roll.

Lennon’s rhythm-guitar right hand would remain one of the Beatles’ most powerful links to the early days of rock music. That same primordial, outsider, wildman spirit pervades his nasty, fuzzed-out lead playing. The distance between Lennon’s solo in You Can’t Do That from 1964 and his leads on 1969’s Cold Turkey is more a matter of years and emotional intensity than of technical or stylistic evolution.

Lennon couldn’t care less about any of that. His emphasis was songwriting, and the guitar was just a support to that. So, for instance, when Lennon learned acoustic folk-picking techniques from folk pop star Donovan during the Beatles’ 1968 meditation retreat in India, it opened up a beautiful new vein in his vastly creative imagination.

This was immediately felt on White Album ballads like Julia and Dear Prudence and would remain another important element in Lennon’s solo work. Along with rock, he was fairly well plugged into folk tradition, something he shared with his fellow rock songwriting icon, Bob Dylan.

Lennon’s approach to guitar was also revolutionized by his avant garde work with Yoko Ono. Accompanying her on live performance pieces like Cambridge 1969, from John and Yoko’s Unfinished Music No. 2: Life with the Lions, he got his first taste of performing without a co-guitarist - or indeed any other instrumentalists of any kind, for that matter.

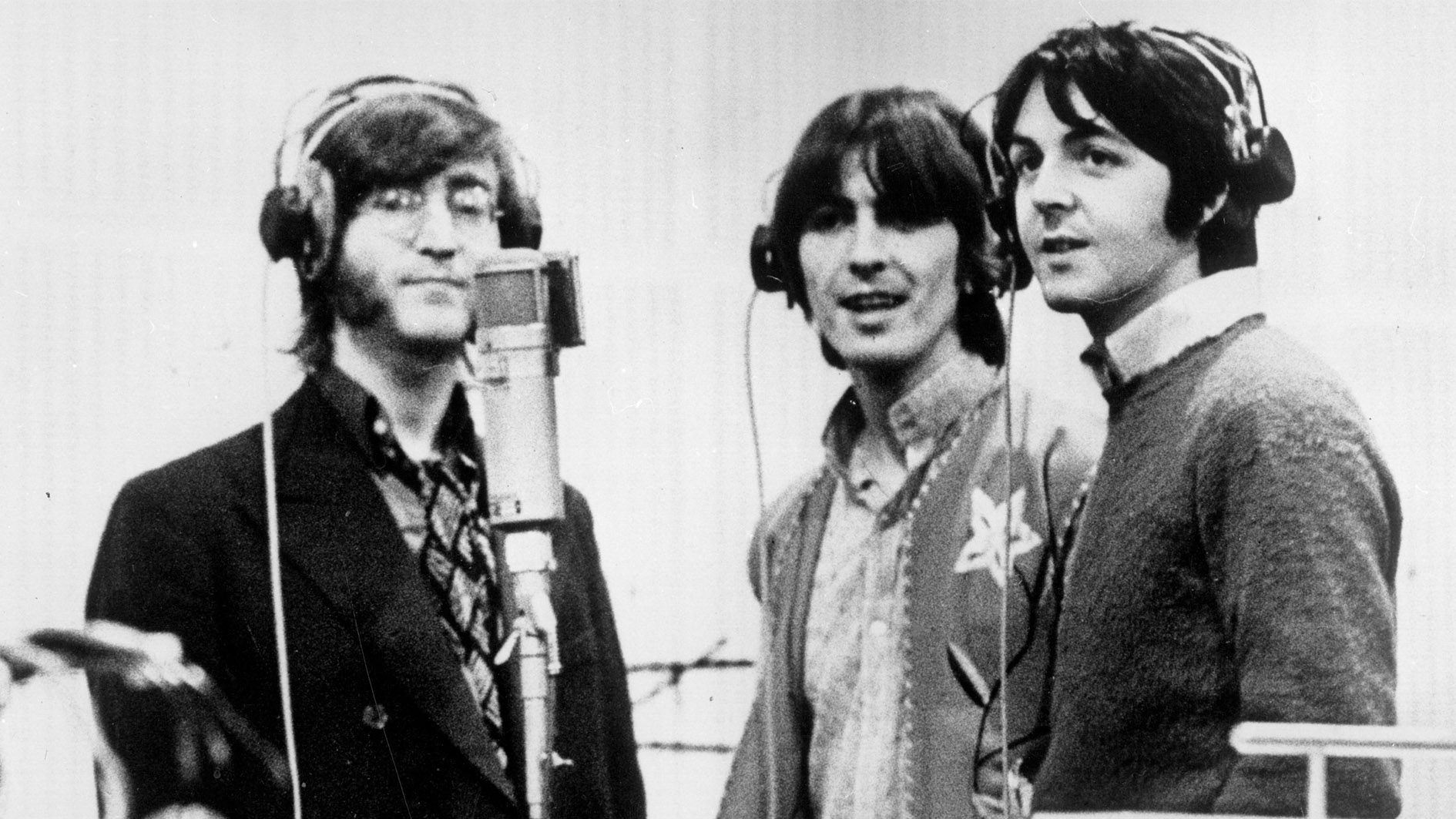

In 1970 John and Yoko underwent Primal Scream therapy with psychologist Arthur Janov. This painful probing and re-experiencing of early life traumas was beneficial for the couple. It also produced one of the most cathartic, important albums in all of rock and roll, John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band.

Deliberately stripping away all the Beatles hype and what he called “production nonsense,” Lennon stands as if naked before us, courageously revealing his fears, his anger and his profound, transformative love for Yoko.

To realize this in musical terms, he called on two of his closest friends, Ringo Starr and Klaus Voormann, to record a series of stark, minimalistic, bone-dry tracks at Abbey Road and at John’s newly built home studio at his Tittenhurst Park estate near Ascot, 30 miles west of London.

While many of the album’s most iconic tracks like Mother and God are piano ballads, Lennon’s scrappy rhythm guitar drives deep album cuts like I Found Out and Well Well Well. On the latter track, the raw urgency of Lennon’s guitar tone forms the perfect complement to his agonized screaming. This is Primal Scream therapy transmuted into electric guitar squall.

In this period, Lennon was relying heavily on his 1965 Epiphone Casino, an archtop electric guitar that had been with him since Revolver. At the prompting of Donovan, Lennon had the Casino’s original sunburst finish sanded away in 1968 in an effort to open up the tone.

The personal becomes political on one of the album’s greatest tracks, Working Class Hero. For this song of revolution, Lennon digs into his folk roots, laying down a classic Anglo- Irish influenced chord progression on an acoustic guitar and outlining the grim options for those marginalized by class or any other system of oppression. While much of the rest of the album was recorded quickly, Lennon labored long and hard on Working Class Hero, laying down more than 100 takes.

The song was an important statement from Lennon, and Plastic Ono Band was the first rock album he’d ever recorded as the sole guitarist.

Coming in the cold winter of the '70s’ inaugural year, John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band hit like a ton of bricks. Those ominous tolling bells and that unforgettable opening line, “Mother, you had me, but I never had you” jolted the rock culture in all their naked, death-haunted, Oedipal/Freudian force.

The album’s stark tone and, at times, painfully confessional lyrics exerted a sizable influence over Roger Waters as he created works like The Wall. And as much as Plastic Ono Band is Lennon mourning his mother, Julia, who died when he was in his teens, it’s also an epitaph for the beautiful dream of the '60s, as Lennon acknowledges in God, advising heartbroken Flower Children that “you’ll just have to carry on.”

Which is exactly what Lennon did for the remainder of his life, creating universal peace anthems, revolutionary manifestos, achingly beautiful love songs and gritty rock and roll in more or less equal measure. His guitars were always a part of that agenda, right up to the end. Photos of his final home in New York City’s Dakota building show that John usually kept a guitar at his bedside.

Paul McCartney - guitar and the consummate pop craftsman

In 1957, Paul McCartney joined John Lennon’s group, the Quarrymen, as a guitarist - a role he retained as the Quarrymen morphed into the Beatles in the late 1950s. But when bassist Stu Sutcliffe left the group in 1961, Paul agreed to switch to bass, albeit with some reluctance: “None of us wanted to be the bass player,” he said. “In our minds, he was the fat guy who always played at the back.”

But once he adopted the instrument, playing his iconic Hofner 500/1 violin bass and later a Rickenbacker 4001S-LH, the left-handed McCartney revolutionized the role of bass guitar in rock music. The driving melodicism of his bass part in Rain and the brilliantly contrapuntal bass line in Fixing a Hole were among the many Beatles tracks that got bassists thinking in wholly new ways about the instrument.

At the same time, though, McCartney never fully relinquished his guitar role within the Beatles. While Yesterday was basically a McCartney solo acoustic guitar-and-vocal performance with orchestral backing, it was nonetheless issued as a Beatles record in 1965.

Paul played lead guitar parts on a number of Beatles tracks, including Another Girl, Taxman, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, Good Morning, Good Morning and Back in the U.S.S.R. This became a source of tension between him and George Harrison as the Beatles began to fall apart.

It’s ironic that McCartney, the Beatle who would go on to have the most prolific and commercially successful solo career, was also the one who most desperately didn’t want the Beatles to end. Let It Be had been a failed attempt partially on his part to keep the group together by getting them back to live performance.

When that turned disastrous, and Lennon told his bandmates that he was leaving the Beatles in September 1969, McCartney fell into a deep depression. He began drinking heavily, making life difficult for his new wife, Linda, and their 7-month-old child, Mary.

It was Linda who assured him that he could have a very successful post- Beatles solo career. Paul bought a Studer four-track recorder and began recording what would become the McCartney album at the couple’s London home.

The project was very secretive. Even when McCartney booked time in a commercial studio, he did so under an assumed name. But he played every single instrument on the album - not just guitars and bass, but also drums and a range of keyboards - and, of course, sang all the lead vocals. The only other person on the disc is Linda, who contributed vocal harmonies. After years of being critical of Ringo’s drumming and George’s guitar playing, Paul was now free to do it all himself.

McCartney is a very intimate album, both sonically and in terms of its subject matter. It’s a quiet celebration of the kind of cozy domesticity that had always been Macca’s stock in trade as a songwriter, from Things We Said Today to When I’m 64.

And while some of the tracks are fragmentary, unfinished or half-baked, there are several very solid songs on the disc. These tend to be ones like Junk, Every Night and Teddy Boy, written during the Beatles years but rejected by the group.

The riff-driven Oo You strikes a proto-metal chord. But the album’s centerpiece is “Maybe I’m Amazed,” a love song to Linda. Macca didn’t muck around on home recording gear for this one. He cut the entire thing at Abbey Road’s Studio 2, scene of many of his artistic triumphs with the Beatles. The song’s highly melodic guitar solo is one of those that even non-musicians can sing note-for-note.

Solo albums by members of prominent rock bands were a new phenomenon in 1970. And McCartney hews close to the original solo disc concept - an intimate glimpse of a great musician letting his hair down a bit, revealing sides of himself perhaps not seen in his more high-profile band work.

McCartney never garnered the same kind of critical acclaim as John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band or All Things Must Pass. It’s more like a tentative first step in what would be a titanic solo career. Perhaps Paul sensed that his musical journey would be a longer one than John or George’s.

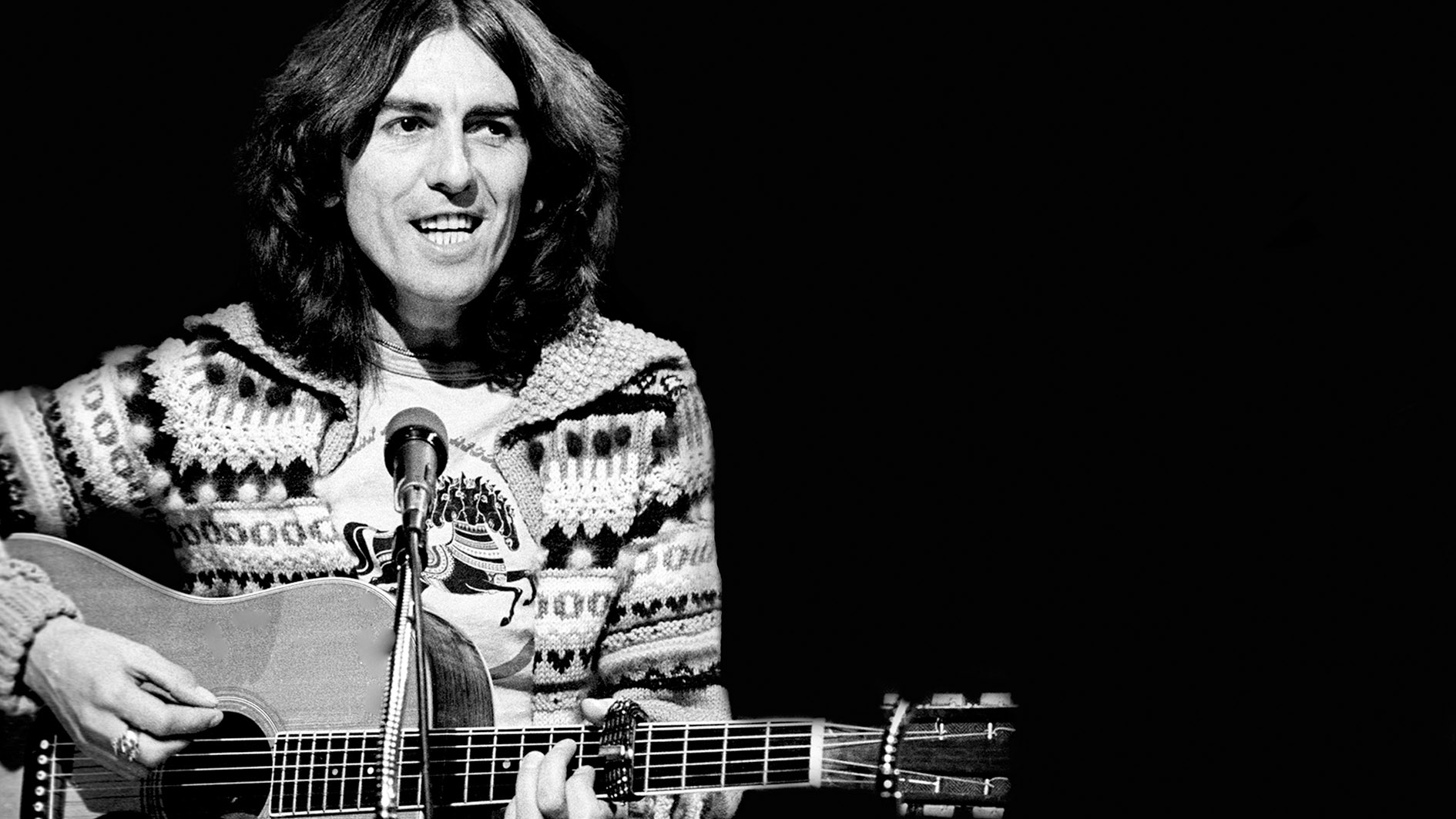

George Harrison - expanding rock’s six-string horizons

Over the course of the Beatles’ spectacular career, the one who grew the most as a guitarist, songwriter, singer and all-round musician was surely George Harrison. His progress had truly been epic - from a Carl Perkins/Chet Atkins-obsessed rock and roll picker to a brilliant musical polymath who revolutionized electric slide playing with his incredibly lyrical and melodic approach.

George’s choice of Gretsch electrics like the Duo Jet, Country Gentleman and Tennessean during the first phase of the Beatles’ career was driven by his reverence for country-based Gretsch players like Atkins and Perkins. For a while, he even adopted the stage name Carl Harrison as a kind of tribute to Perkins.

This comes across clearly in recorded performances like George’s rockabilly-inflected solo in Can’t Buy Me Love and his lead vocal and lead guitar work on the Beatles’ cover of Everybody’s Trying to Be My Baby.

Delaney handed me a bottle-neck slide - I had not tried slide before, so I started at that time to play with the bottle-neck

George Harrison

Harrison’s style evolved in another direction in early 1964, when he received the second Rickenbacker 360 12-string electric guitar ever made. The electric 12 was new, and its success had a lot to do with Harrison’s iconic 12-string work on tracks like You Can’t Do That, I Call Your Name and Ticket to Ride.

But the real quantum leap in Harrison’s musical evolution was his immersion in Indian music and study of the sitar with Indian virtuoso Ravi Shankar. This utterly changed his approach to phrasing and melodic construction, as heard on every inch of 1969’s Abbey Road, particularly Something, Octopus’ Garden and You Never Give Me Your Money.

And while Lennon and McCartney had each turned inward at the time of the Beatles’ demise - retreating to home turf to lick their wounds and release introspective solo albums - Harrison had turned outward. With his close friend Eric Clapton, he hit the road as part of the backing band for blue-eyed soul duo Delaney and Bonnie.

This tour was when “George Harrison, slide guitarist” was born. “We were on a tour of Europe and [Delaney and Bonnie] released their record Coming Home,” Harrison wrote in his limited-edition autobiography, I Me Mine. “Delaney handed me a bottle-neck slide and asked me to play a line which Dave Mason had played on the record. I had not tried slide before, so I started at that time to play with the bottle-neck.”

Clapton gave George the Leslie 147 tone cabinet used on Abbey Road and during his solo career. With this, Harrison pioneered yet another iconic guitar sound. In the same period, George’s friendship with Bob Dylan grew closer. The two had first met in 1964, when Dylan went round to the Delmonico hotel in New York to meet the Beatles for the first time and, as it turned out, turn them on to pot.

In 1968, as tensions escalated during the making of the Beatles’ White Album, Harrison spent some time with Dylan and the Band in Woodstock, New York, and had been struck by the egalitarian spirit of their work together at Big Pink, at a time when Dylan was one of the biggest rock stars on the planet. George couldn’t help but compare that with the situation back at Abbey Road in London, as Paul McCartney grew more and more assertive in his desperate effort to keep the Beatles’ ship from sinking.

“I found I was starting to enjoy being a musician again,” George said, “but the moment I got back with the Beatles, it was just too difficult.”

Harrison’s electric slide work and gorgeous chorused timbres are key elements in the glorious sonic tapestry of his 1970 triple-disc album, All Things Must Pass. By this point, he’d written recorded and released an Indian-influenced soundtrack album for the 1968 film Wonderwall and an album of mad Moog experimentation, 1969’s Electronic Sound.

I found I was starting to enjoy being a musician again, but the moment I got back with the Beatles, it was just too difficult

All of these musical experiences, along with a rich backlog of songs that hadn’t made it onto Beatles records, would go into the creation of All Things Must Pass. Not to mention the poetry, music and wisdom George had absorbed from Indian culture and cross-bred with the primordial truth of rock and roll.

As the Beatles’ live guitar team, Harrison and Lennon forged a close bond, often ordering guitar models in pairs - Gibson J-160Es, Epiphone Casinos, Fender Strats - like some sort of six-string twin act.

But during the late '60s, a shared interest in both hallucinogens and spirituality brought them even closer. So it’s not surprising that George, like John, chose to record his debut record as a fully-fledged solo production with Phil Spector as his co-producer and the quickly gelling rhythm section of Ringo Starr and Hamburg friend Klaus Voormann providing the foundation.

But unlike Lennon and McCartney in their solo debuts, Harrison didn’t just work with a small core of musicians or try to do everything on his own. He basically opened up Abbey Road and his Friar Park home to all the great musicians he’d been interacting with.

Clapton played, as did all of his new group, Derek and the Dominoes. Peter Frampton and Dave Mason are two of the other notable guitarists who contributed to the sessions. Other legendary musicians who lent their talents included Ginger Baker, Billy Preston, Alan White and Gary Brooker.

In lesser hands, a project of this scope and magnitude may have spiraled out of control and become self-indulgent. But George Harrison was an artist who could assimilate myriad musical influences without losing sight of his core identity.

All Things Must Pass was the first major statement of a solo career that would delight, and often surprise, fans over the course of three decades.

In a career that spans five decades, Alan di Perna has written for pretty much every magazine in the world with the word “guitar” in its title, as well as other prestigious outlets such as Rolling Stone, Billboard, Creem, Player, Classic Rock, Musician, Future Music, Keyboard, grammy.com and reverb.com. He is author of Guitar Masters: Intimate Portraits, Green Day: The Ultimate Unauthorized History and co-author of Play It Loud: An Epic History of the Sound Style and Revolution of the Electric Guitar. The latter became the inspiration for the Metropolitan Museum of Art/Rock and Roll Hall of Fame exhibition “Play It Loud: Instruments of Rock and Roll.” As a professional guitarist/keyboardist/multi-instrumentalist, Alan has worked with recording artists Brianna Lea Pruett, Fawn Wood, Brenda McMorrow, Sat Kartar and Shox Lumania.