Why The Byrds' Roger McGuinn is one of rock's greatest guitar heroes

In general, Roger McGuinn has gotten more love from the rock critic fraternity than from the guitar community. Maybe it’s time to turn that perception around

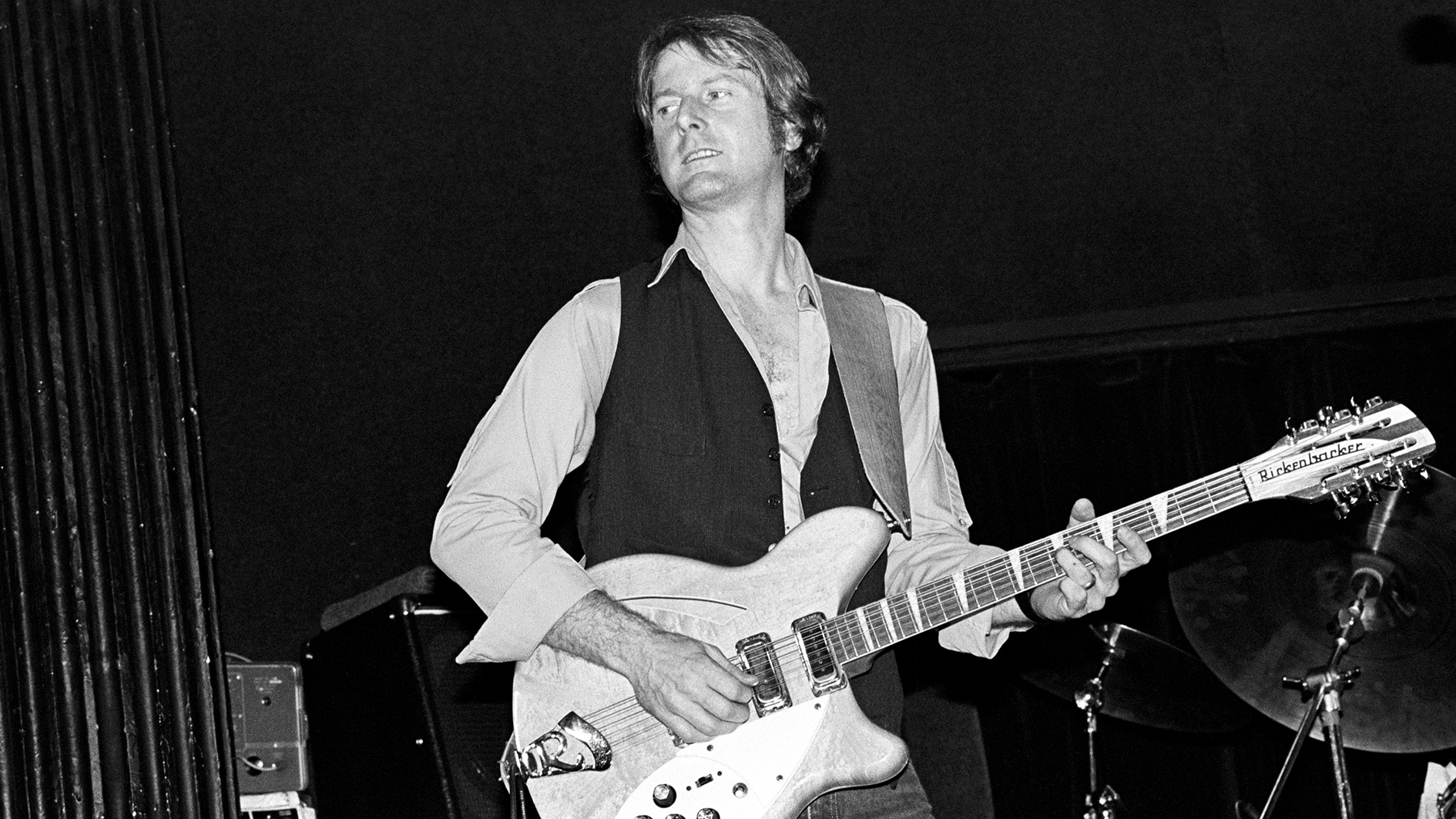

In November 1990, I sat in the control room at Capitol Records’ Studio B in Hollywood and watched Roger McGuinn record 12-string electric guitar overdubs for Someone To Love, the lead track from his Back From Rio album, released in ’91.

The room was awash in that glorious, plangent Rickenbacker jangle that is McGuinn's greatest gift to the rich lexicon of rock guitar styles.

I was both impressed and inspired by his nuanced command of the signature model Rick 370/12 he was playing at that time - trying out subtle variations in phrasing, punching in a pull-off trill to end a line more gracefully.

There was something familiar in the song’s ascent from E minor to G major, via a D passing chord with F# in the bass. Producer David Cole called out, “Hey, how does Eight Miles High go?” Without missing a beat, McGuinn played the entire iconic solo that he’d recorded nearly a quarter of a century earlier, note-for-note, flawlessly.

Because I’d started playing guitar in the mid '60s, McGuinn had always been a major hero. Not just for his playing and singing, but also the aura of serene cool he emanated back when he was still called Jim McGuinn.

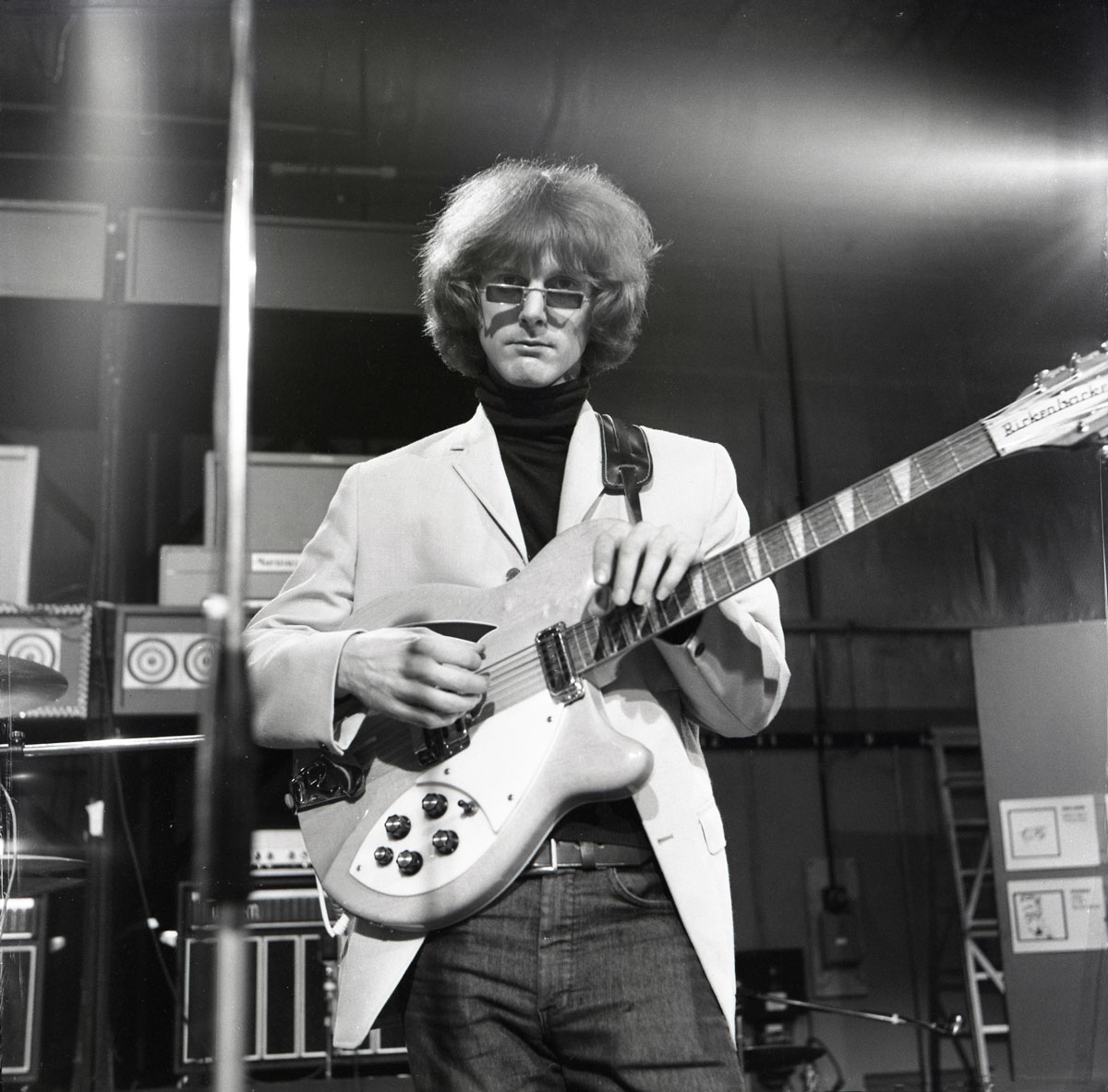

In junior high school, I’d had my McGuinn-style “granny” sunglasses confiscated by the school’s Dean of Discipline. Lots of kids wore them. Factories started mass producing the things when McGuinn’s band, the Byrds, became one of the biggest rock groups on the planet with the 1965 release of their debut single, an electrified cover of Bob Dylan’s Mr. Tambourine Man.

At the vanguard of the folk rock phenomenon, the Byrds were the bridge that led from the British invasion into the psychedelic era. They’re the pied pipers who transported us from “yeah yeah yeah” to Purple Haze, basically.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

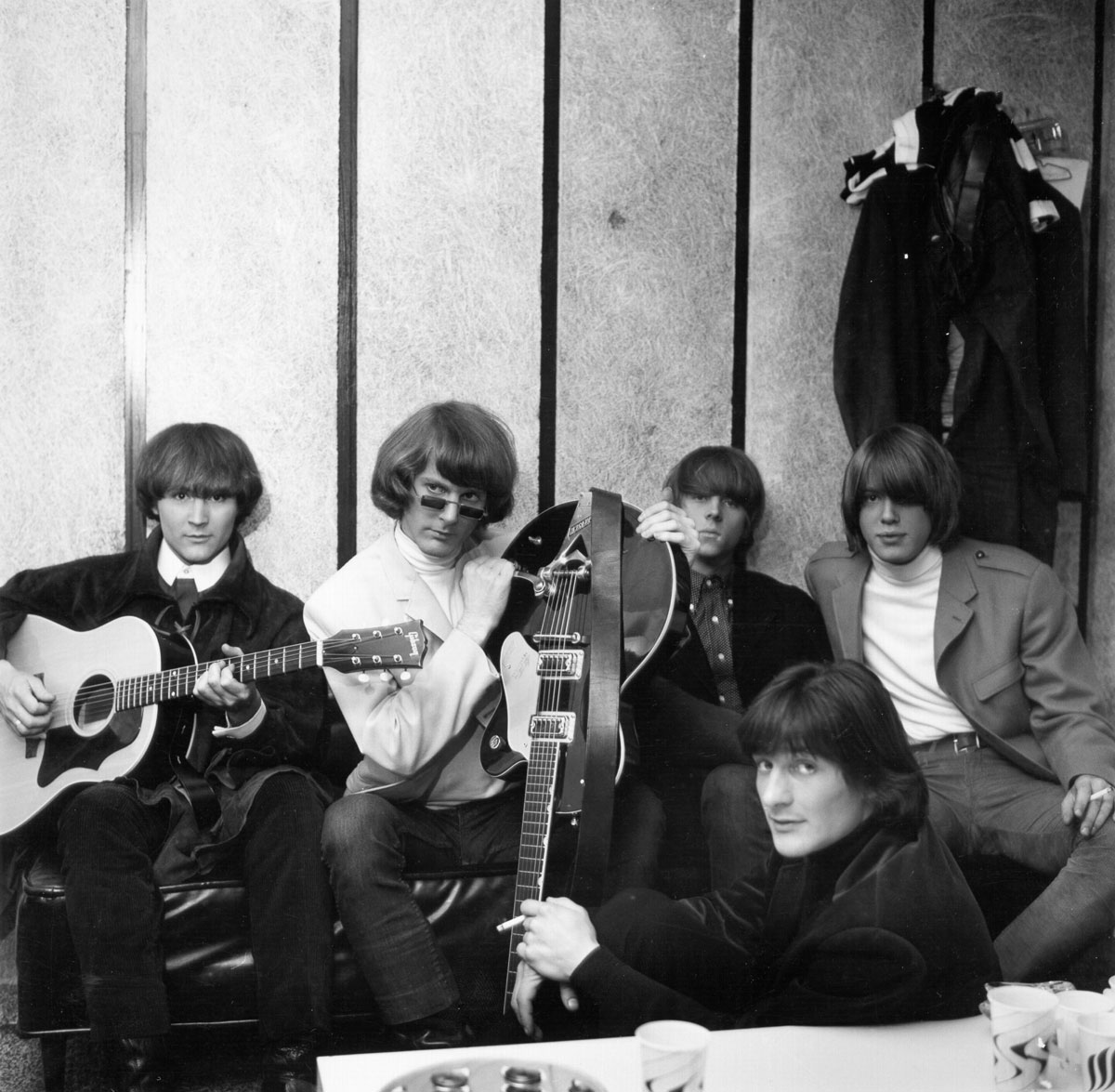

George Harrison proclaimed the Byrds “The American Beatles.” Like Bob Dylan himself, the Byrds were, for the most part, seasoned folk musicians who’d become fascinated by the new style of electric guitar rock and roll that the Beatles, Rolling Stones, Kinks, Yardbirds, Animals and other British groups had brought to the fore.

“We were already a band and we were rehearsing and working with acoustic instruments,” McGuinn told me. “We saw A Hard Day’s Night and realized the Beatles were playing a Gretsch electric six-string, Ludwig drums and a Hofner bass.

And George Harrison switched between the Gretsch and this Rickenbacker 12-string that didn’t look like a 12-string at first, because the peghead concealed six of the tuners.

But when he turned sideways, I went, ‘Oh that’s a 12-string!’ I was playing a Gibson acoustic 12 with a pickup in it, but it didn’t have the kind of sound George was getting. I liked his sound better, so I went out and got a Rickenbacker 360 12-string.”

While McGuinn and his bandmates had the same gear as the Beatles, they used it to produce a distinctly different sound and overall aesthetic. What McGuinn brought to electric 12-string rock guitar was a solid grounding in folk picking - something that Harrison and other Rick-playing Brits, such as Pete Townshend, didn’t have.

As a teenager in Chicago, McGuinn had studied guitar and five-string banjo at the Old Town School of Folk Music, a pioneering institution at a time when formal instruction in vernacular musical styles like folk was unheard of.

“They started around 1957,” McGuinn recalled, “and that’s when I enrolled. I was there from ’57 to 1960. I learned a lot there. I studied with [seasoned folk musician and Old Town founder] Frank Hamilton.

"There would be about twelve people in a class, and it was really fast learning. He’d give you a picking assignment every day. I’d go home and work on it, and we’d get another one the next day. Gradually, I got all these picking styles.”

From there, McGuinn went on to work with several prominent acts in the early-'60s folk music boom - the Limeliters, the Chad Mitchell Trio, Judy Collins and even pop crooner Bobby Darin during his brief attempt to get down with the folk thing.

It was really fast learning. I’d go home and work on it, and we’d get another one the next day. Gradually, I got all these picking styles

Roger McGuinn

McGuinn had sufficient traction on the folk scene to be included on the 1963 compilation album Anthology of the 12-String Guitar, along with legendary players like Joe Maphis, Glen Campbell, Mason Williams and Howard Roberts.

Because he was a fairly seasoned pro, and able to read music, McGuinn was the only member of the Byrds allowed to play on Mr. Tambourine Man. All other parts were played by members of the Wrecking Crew, L.A.’s famed coterie of session musicians.

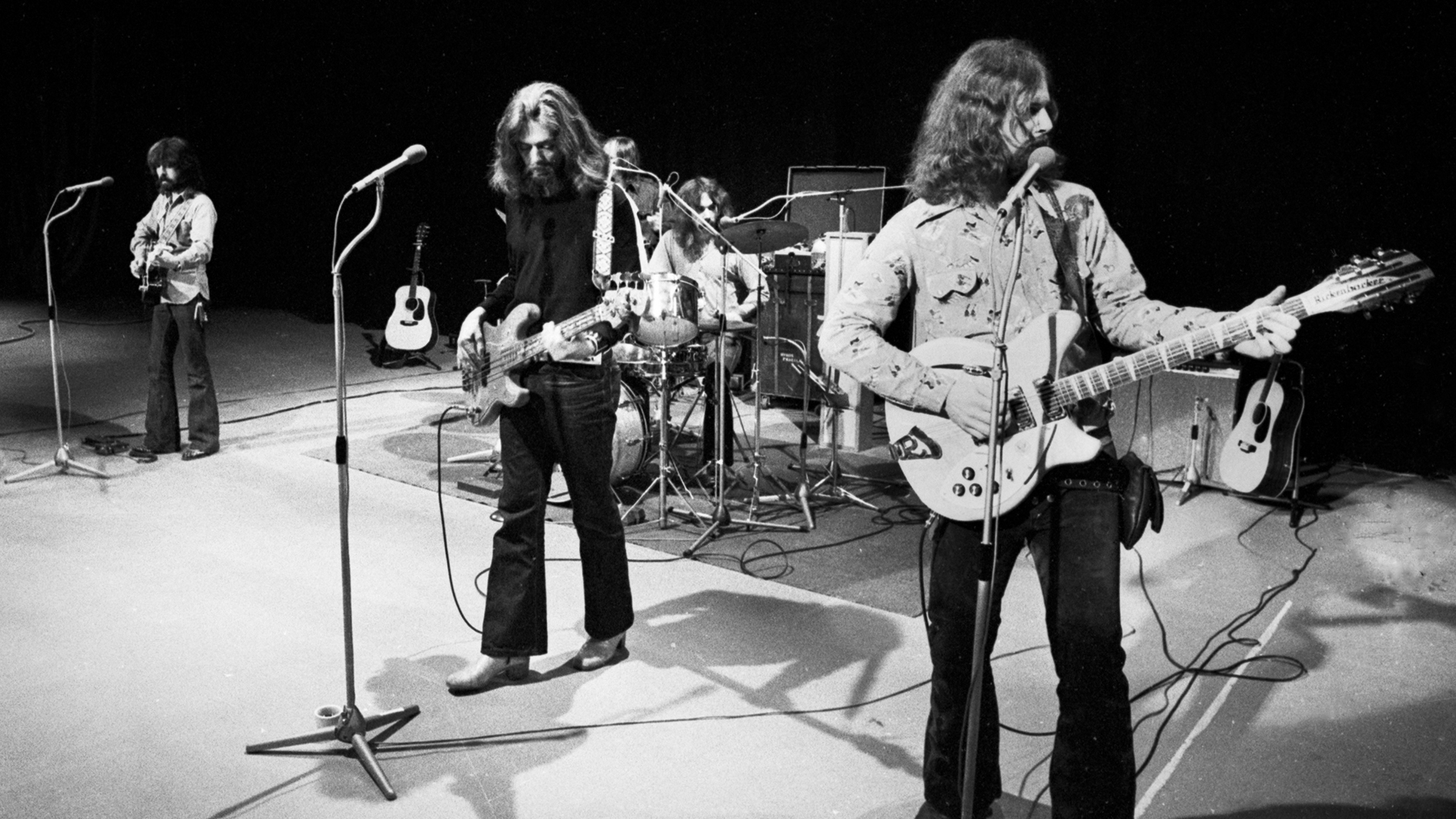

But McGuinn’s fellow Byrds David Crosby and Gene Clark were allowed into the studio to sing the track’s majestic, three-part vocal harmonies. All subsequent Byrds recordings, however, were played and sung by the full group, which at the time also included bassist Chris Hillman and drummer Michael Clarke.

The electric 12-string guitar was a brand-new innovation in 1964, when the Rickenbacker 360/12 became the first commercially successful model of that type.

The one Harrison received from the company in February of ’64 was only the second ever made. So the field was wide open for players like McGuinn and Harrison to forge a place for this new instrument in rock music.

McGuinn’s guitar work on Mr. Tambourine Man says it all. Dylan’s song is a masterpiece in its own right - an imagistic, dreamscape lyric that transported the listener to another realm of consciousness. And Dylan’s own recording of his composition has a wistful, intimate quality that is deeply affecting.

Like the Beatles, the Byrds had an ultra-cool image, with Crosby’s leather capes and McGuinn’s rectangular shades perched on the end of his slender nose

But McGuinn and the Byrds made rock ‘n’ roll of it. That much is clear from the first notes of the chiming, devastatingly infectious guitar hook McGuinn crafted as the intro to the Byrds’ interpretation of the song.

This was a musical singularity moment. As a rock and roll group, the Byrds had the ability to reach teenage listeners who might have still found Dylan a little too “out there.”

It was the Byrds, not Dylan, who played on youth-oriented pop music TV shows like Shindig and Hullabaloo. Like the Beatles, the Byrds had an ultra-cool image, with Crosby’s leather capes and McGuinn’s rectangular shades perched on the end of his slender nose.

Added to this, they sang beautiful harmonies and knew how to lay down a groove.

“David [Crosby] learned to play rhythm guitar like John Lennon,” McGuinn recalled, “and I tried to learn to pick and keep a beat. That was a major concern, because we came from folk music, where the beat wasn’t very important. You could skip a beat, speed up or slow down. It didn’t make any difference, as long as you got the story across.

But now we were playing in places where people were dancing to our music, and what we were concentrating on the most was trying to keep a beat.”

For McGuinn, this meant modifying some of the folk picking techniques he’d learned earlier on. “I’m a two-finger kind of player,” he said. “Mostly, I played with the thumb and two finger picks. Then, when I joined the Byrds, I had to use a plectrum to play leads, so I switched my style from thumb and two fingers to a flat pick between my thumb and forefinger and two finger picks on my middle and third fingers. I switched the same kind of rolling style over to that.”

What McGuinn did, in essence, was bring the grand, 12-string acoustic folk tradition of Leadbelly and Pete Seeger into the rock arena. The Byrds notably covered two of Seeger’s compositions, Turn! Turn! Turn! and The Bells of Rhymney.

These songs, along with Dylan covers like Chimes of Freedom, The Times They Are A’ Changin’ and My Back Pages, helped bring a political sensibility and sense of social consciousness into rock music. This was the great, mid-'60s era of protest music, aligning the power of rock and roll with folk music’s long, outspoken tradition of championing the oppressed and decrying the brutal insanity of war.

It’s amazing to reflect on how much of this came about because McGuinn attended a screening of A Hard Day’s Night when it first came out.

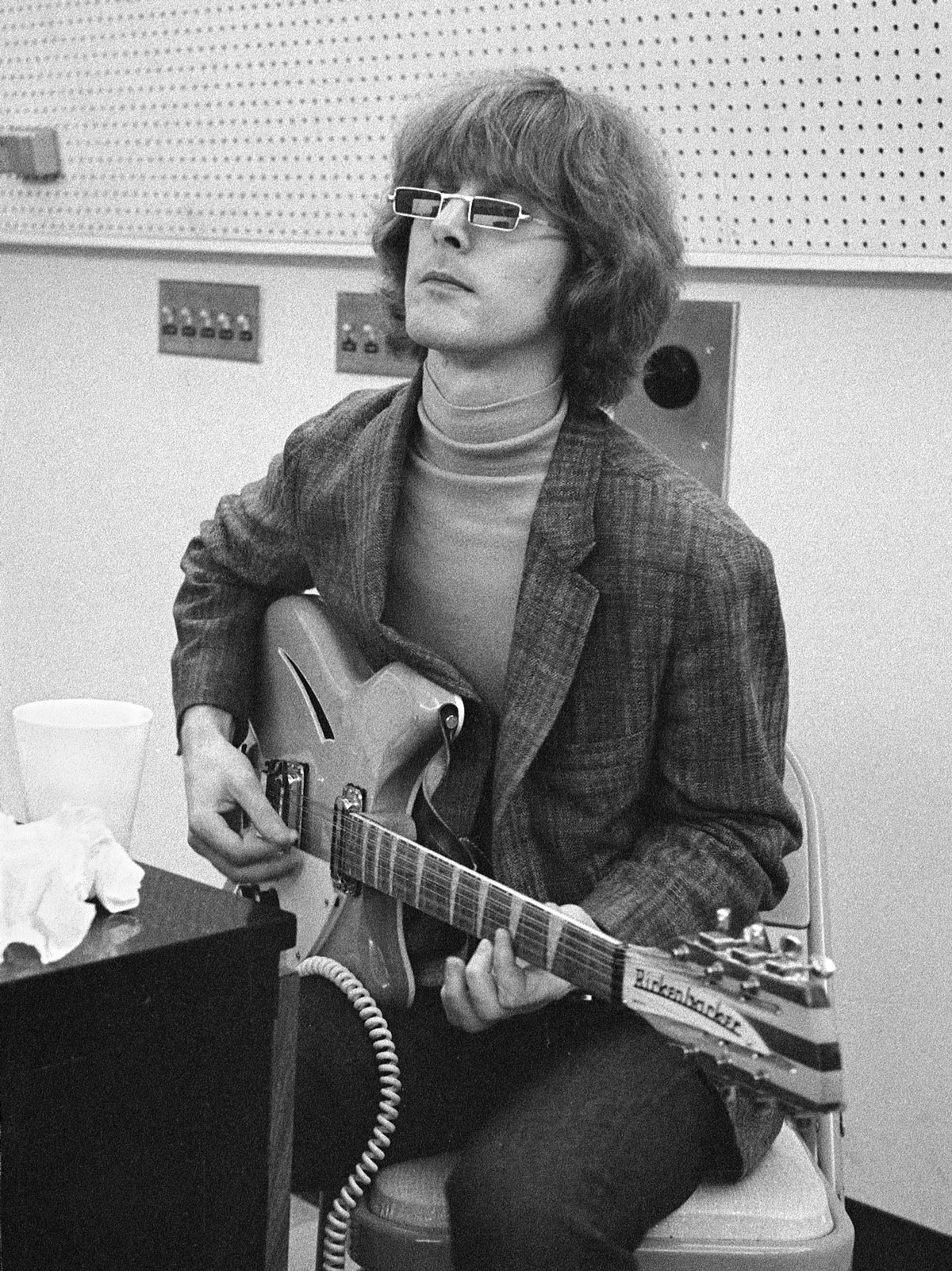

The other thing that distinguished McGuinn’s Rick 12 sound from Harrison’s was loads of compression, provided by analog processing gear at Columbia Studios and other facilities where the Byrds recorded.

“We used to use Fairchild compressors and Pultec limiters,” McGuinn elaborated. “The technique was to run one compressor into another - piggyback them - just to get as much compression as possible to get as much sustain as possible. Because the Rickenbacker is a very short-sustain instrument. That’s good for rhythm, but it’s not good for lead.

They always limited everything as a matter of course. We said, ‘Hey that sounds pretty good!’ So we used more of it and we got that sound accidentally

Roger McGuinn

"The lead lines I was doing needed longer sustain. So we used compression. Originally, though, I think the reason why we started using compression wasn’t for the sustain. It was a by-product of the fact that [recording engineers] did it so that we wouldn’t blow up their equipment.

They always limited everything as a matter of course. We said, ‘Hey that sounds pretty good!’ So we used more of it and we got that sound accidentally.”

McGuinn took that sustained Rickenbacker sound, and the Byrds’ music, in a new direction with the group’s 1966 recording Eight Miles High, the lead single from their Fifth Dimension album, released that same year.

The track’s beginning, middle and end feature frenetic flights of modal riffing and improvisation on McGuinn’s electric 12-string. It’s one of those pioneering mid-'60s tracks where, for the first time, the guitar soloing carries as equal weight as the lyric and vocal performance.

The genealogy of Eight Miles High is a bit complex. It was directly influenced by the work of the groundbreaking avant-garde jazz saxophonist John Coltrane. But Coltrane, in turn, had fallen under the spell of Indian classical music in the early '60s.

A few short years later, the Indian influence started filtering into rock music as well, spearheaded largely - but not exclusively by the Beatles. So there’s a tangled and fascinating tide of musical cross-currents driving McGuinn’s landmark 12-string electric guitar work on Eight Miles High.

His tone is markedly different from the chiming cadences of the Byrds’ previous two albums. It’s harder, edgier, more ragged, although forged from much the same basic ingredients - a super-compressed Rick 12.

“There’s quite a bit of sustain on the solo,” McGuinn explained to me. “It’s just that there’s no reverb. It’s kind of dry. But there is sustain, and I’m just playing soft notes. The sustain is what allowed me to do the saxophone emulation I was doing.

The continuous flow of air in a saxophone with the valves cutting it off is what I was doing with the sustain, and making short, clicking kind of notes on the break.” Eight Miles High was a key track in the emergence of psychedelic rock in ’66, and particularly the Indian-inflected psychedelic subgenre known as raga rock.

Owing to the word “high” in the lyric and some of the imagery, it was perceived as a “drug song” at the time, and was banned as such by several radio networks.

The song’s subject was actually a plane flight the group took to London. Soon enough, though, San Francisco bands like Jefferson Airplane and Quicksilver Messenger service would show us what a real psychedelic drug song sounds like.

Of course, McGuinn and the Byrds weren’t the exclusive progenitors of all this trippy, Indian-flavored bliss. Jeff Beck had adorned the Yardbirds’ single Heart Full of Soul with a droning, sitar-like riff in the summer of ’65, some nine months before the release of Eight Miles High.

The Beatles, of course, had introduced the sound of the sitar to rock music, played by George Harrison, on Norwegian Wood as early as December of ’65. And some five months after the release of Eight Miles High, the Beatles unleashed their own mystical and hypnotic raga rock masterpieces, Tomorrow Never Knows and Love You To, both from Revolver.

It’s all part of the heady transatlantic, transglobal exchange between British and American rock groups that made the mid-to-late Sixties a time of blindingly rapid evolution in rock music.

The Byrds and The Beatles famously hung out together as part of L.A.’s Laurel Canyon rockstar enclave during the summer of ’65, tripping on LSD, talking music and strumming guitars

By today’s standards, every year back then was like a decade. And it was very much the Byrds who had commenced this Anglo-American dialog.

Their relationship with the Beatles was a particularly close one. George Harrison was quick to acknowledge McGuinn’s influence on his own playing, publicly admitting that his Beatles composition If I Needed Someone had been inspired by McGuinn’s guitar work on the Byrds’ recording of The Bells of Rhymney.

The two groups famously hung out together as part of L.A.’s Laurel Canyon rockstar enclave during the summer of ’65, tripping on LSD, talking music and strumming guitars together.

According to some accounts, this is where Harrison first discovered Indian music and sitar master Ravi Shankar. David Crosby had been hanging out at World Pacific Studios in L.A., where Shankar had made some albums. He soon had all the guitar-playing Byrds riffing ersatz ragas on open-tuned 12-string acoustics.

“So one day we went over to the Beatles’,” McGuinn recounted. “Once we became friends with them, they would send a limo over to get us and bring us to their house in the hills when they were in town.

"One day we’re up there and we all took acid. We were sitting around on the bathroom floor playing guitars, and Crosby started playing all this Indian stuff on his 12-string. George was very interested in it. He’d never heard it before. He went out wild with that stuff.”

So why isn’t McGuinn’s name intoned today with the same awed reverence that attends any mention of names like Clapton, Hendrix or even Harrison for that matter? A lot of it has to do with the fact that, by the late '60s, distorted, blues-based riffing had become the normative mode of rock guitar playing.

This perception was reinforced in the early '70s when the Lee Abrams format narrowed the FM rock radio playlist so that stations could attract a larger listenership and bigger ad revenues.

A lot of what was weird and wonderful - from folk to many African-American musical idioms - fell by the wayside.

Blues-based riffing through big Marshall amps is a vital part of rock music, to be sure. But it’s not the whole story. And it was never McGuinn’s thing. For one, it isn’t particularly easy to bend notes on a Rick 12.

“It’s a hard one to bend,” McGuinn explained to us. “We did a couple of bending kind of things. There was a song called Captain Soul on Fifth Dimension. But the Byrds weren’t a blues-inspired band.

"We were more of an Appalachian traditional folk-inspired and English/Irish folk music-inspired band. Although David Crosby was a little more blues-inspired than the rest of us.

“Although, as a funny kind of footnote, when I went to the Old Town School of Folk Music in Chicago, Mike Bloomfield was there at the same time. I’d been in the school for about a year before he got there. I was one of the first people to enroll at the school and I had progressed up to the advanced classes.

So one day Mike came up to me. He poked me and said, ‘I’m gonna get better than you.’ And then he said, ‘You know that sound - that mmmmmm?’ And he emulated bending a string.

‘How do you get that?’ And I showed him how to do that. It’s funny - I taught Mike Bloomfield how to bend a string.” McGuinn’s visage certainly deserves to be emblazoned up there on the Mount Rushmore of Important Guitarists.

But, truth to tell, the Byrds’ career went into a bit of a tailspin after their 1967 album Younger Than Yesterday, which featured the ironic, iconic classic So You Want to Be a Rock ‘n’ Roll Star. Gene Clark and David Crosby - two key songwriting contributors - both left the band, followed shortly thereafter by Michael Clarke.

The lineup fluctuated as McGuinn and Hillman worked on the followup, The Notorious Byrd Brothers. Given that Hillman had a very solid background in bluegrass music, the musical direction started steering more toward country music.

Helping solidify this new impetus was the arrival of celebrated country/bluegrass guitarist Clarence White in the Byrds’ orbit. The inventor, along with drummer Gene Parsons, of the Parsons/White B-Bender for the Fender Telecaster, White first entered the picture as a session player on the Byrds’ Younger Than Yesterday album and would become a full-time member in 1968.

McGuinn was gracious about sharing the guitar limelight, as happy to learn as to teach.

“I tried to learn some things from Clarence,” he told me, “but I couldn’t touch him. He was miles and miles ahead of me as far as the techniques he perfected - like that bending thing he did. And his flat-picking, his bluegrass stuff, I couldn’t touch that.

[Clarence] was miles and miles ahead of me as far as the techniques he perfected

Roger McGuinn

"He was so fast and so clean. He tried to teach me to do [traditional string-band standard] Soldier’s Joy, but I couldn’t get near it.”

From Elvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis and Carl Perkins onward, country had never not been a part of rock and roll music. It is an essential part of rock’s DNA. The Beatles had covered Buck Owens’ Act Naturally in 1965.

The Lovin’ Spoonful had scored the 1966 hit, Nashville Cats, with some stone country licks from guitarist Zal Yanovsky.

McGuinn himself had gone full twang with the Byrds, with songs like his inspired 1966 sci-fi country track Mr. Spaceman.

But in 1968 America was a very polarized country - with racial violence mounting in the wake of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, and resistance to the Vietnam War growing militant under a President, Richard Nixon, headed for impeachment.

And among the counterculture crowd that had been the Byrds’ main audience, country music had become somewhat stigmatized as right wing conservative music - a soundtrack for the Ku Klux Klan.

That’s why it was incredibly brave and daring for McGuinn and the Byrds to release an album like Sweetheart of the Rodeo at that particular moment.

Now recognized as a classic, it was a tough sell back in the tumult of 1968. Many a hippie head was scratched, wondering what to make of the Byrds doing songs like the Louvin Brothers’ The Christian Life. Was it ironic? A joke, right? Had to be.

McGuinn had recently begun using a new name - Roger - rather than his given name, James. It was part of his embrace of the Subud spiritual tradition. The whole thing was almost like some proto-Bowie-esque shift in persona.

But the music’s beauty and originality eventually won the day. Legendary players abound on Sweetheart, including pedal steel masters Lloyd Green and JayDee Maness, and fiddle/banjo/guitar ace John Hartford.

McGuinn plays five-string banjo on some tracks and Hillman plays mandolin. Along with songs by iconic tunesmiths like Bob Dylan, Woody Guthrie and Merle Haggard, the album bears the stamp of another new arrival to the Byrds camp, soon-to-be country rock legend Gram Parsons.

A brilliant songwriter, Parsons was a conflicted Catholic rich boy from Florida. He was deeply steeped in country tradition but brought an edgy new sensibility to the music.

Sweetheart of the Rodeo introduced listeners to the classic Parson songs Hickory Wind and One Hundred Years from Now. McGuinn wound up splitting lead vocal duties fairly evenly with Parsons and Hillman on Sweetheart of the Rodeo.

“Gram was a strong musical force,” McGuinn said. “I just kind of let him go and went along with it - because it was fun. I really got into the country thing. We went to Nudie’s, the Western tailor, and got some country clothes and cowboy hats. I got a Cadillac, started listening to country radio and talking in a Southern accent.”

McGuinn’s total assimilation of the country songwriting idiom can be heard on his sardonic co-write with Parsons, Drug Store Truck Drivin’ Man. It helped launch a whole subgenre of “hippie goes country” tracks like the Fraternity of Man’s Don’t Bogart Me (a.k.a., Don’t Bogart That Joint) and the Holy Modal Rounders’ If You Want to Be a Bird.

Both of those songs were featured on the soundtrack to the 1969 counterculture cult classic film, Easy Rider. McGuinn himself is all over the film soundtrack album, with a Byrds track, Wasn’t Born to Follow, and solo acoustic performances of Dylan’s It’s Alright Ma (I’m Only Bleeding) and a new song which he co-wrote with Dylan himself, Ballad of Easy Rider.

But McGuinn had no intention of spending the rest of his career in a Nudie suit. He began to clash with Parsons, who wanted to change the group’s name to Gram Parsons and the Byrds, among other things.

Parsons and Hillman exited the Byrds to found the seminal country rock group the Flying Burrito Brothers.

“To me, Sweetheart of the Rodeo was a one-time adventure,” McGuinn said. “I had no idea of getting permanently into country music. Chris and Gram wanted to do another country album and I was going, ‘No, no, no! Wait a minute. That’s enough.’

"They were so upset that Chris left, and he and Gram started the Flying Burrito Brothers. I wasn’t into it. I mean, I like the Flying Burrito Brothers. I was amazed at the quality of the first album that materialized.

"But it wasn’t the direction I wanted to go in. I wanted to play rock and roll.” But McGuinn kept Clarence White in the ever-changing Byrds lineup from that point until just before all five original band members recorded a reunion album - Byrds - in 1973.

McGuinn and White’s dual guitar work garnered some critical recognition, but the commercial success of the Byrds’ early days had become a thing of the past.

We kept moving around in hopes that we would escape the labeling system - a moving target is harder to shoot

“The Byrds’ attitude had been - and this was another Beatles influence - to keep changing directions,” McGuinn said. “So you couldn’t be categorized as a country group or a rock and roll group, or ‘they play folk music’ or ‘they play folk-rock.’

"First of all, we hated those labels. Didn’t want to be any one of those things. So we kept moving around in hopes that we would escape the labeling system. As it turns out, they just made up new labels as we went along. But our intent was to keep moving. A moving target is harder to shoot.”

The same restless creative spirit has pervaded McGuinn’s solo career. There’s been more work with Dylan, as well as Chris Hillman and Gene Clark, plenty of one-man shows and even a brief flirtation with electronic music.

“Actually, I did go through a period in the mid '70s when I was kind of lost,” he admitted in 1990. “I wasn’t sure what direction I wanted to go in. And it wasn’t until the late '80s, I guess, that I decided I wanted to get back to what I was originally into, which was my 12-string electric guitar, my vocal sound and just doing what I do.”

By that point, the punk/new wave scene had long opened up a fresh space for such historically conscious, back-to-basics rock groups as Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers and R.E.M., who seemed to bring the McGuinn 12-string sound and overall sensibility back into the foreground.

He is the godfather of the entire jangle pop genre and a key figure in the range of styles known today as Americana.

In general, Roger McGuinn has gotten more love from the rock critic fraternity than from the guitar community. Maybe it’s time to turn that perception around. There are guitar heroes who are esteemed for their technical flash. But there are others - like Pete Townshend, for example - whose sterling guitar work is sometimes upstaged by their contributions as songwriters, singers, trendsetters and tastemakers.

Guitarists whose sound is so inextricably woven into the fabric of rock music that the whole thing would be unthinkable without them. That’s the kind of guitar hero that Roger McGuinn is.

In a career that spans five decades, Alan di Perna has written for pretty much every magazine in the world with the word “guitar” in its title, as well as other prestigious outlets such as Rolling Stone, Billboard, Creem, Player, Classic Rock, Musician, Future Music, Keyboard, grammy.com and reverb.com. He is author of Guitar Masters: Intimate Portraits, Green Day: The Ultimate Unauthorized History and co-author of Play It Loud: An Epic History of the Sound Style and Revolution of the Electric Guitar. The latter became the inspiration for the Metropolitan Museum of Art/Rock and Roll Hall of Fame exhibition “Play It Loud: Instruments of Rock and Roll.” As a professional guitarist/keyboardist/multi-instrumentalist, Alan has worked with recording artists Brianna Lea Pruett, Fawn Wood, Brenda McMorrow, Sat Kartar and Shox Lumania.