Steve Vai Discusses Devin Townsend and New Album, 'Sex And Religion,' in 1993 Guitar World Interview

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

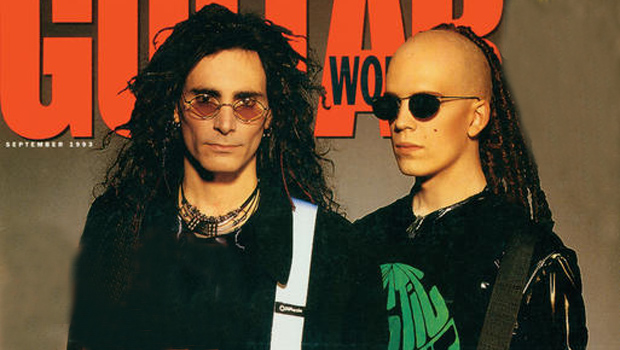

This interview with Steve Vai appeared in the September 1993 issue of Guitar World. It appeared with the simple headline, "Obsession."

“The title of this interview,” Steve Vai jokes, “should be ‘Sorry Folks, I Can’t Help Myself.’”

I suppose he can’t. On several levels, Vai is one of rock’s great obsessive personalities. Fidgeting in the control room of his studio in the Hollywood Hills, he’s surrounded by the results of one burning obsession: his quest for the ultimate guitar tone and the most bitchin’ hard rock tracks this side of Venus. The room is piled high with effects racks, MIDI gear and other electronic devices - an imposing techno landscape relieved only by the occasional poster of a babe on a Harley.

The gear selection reflects the guitarist's tireless inquiry into the nature of sound itself. When Steve Vai says "I've put a lot of research into this," you'd best believe him -- whether the topic is the ideal way to mount a whammy bar or the true meaning of the Holy Trinity.

See, like many nice Italian boys from Long Island, New York, young Stevie grew up fixated on sex, religion and guitars. He explores all three in great detail on his new album, titled -- aptly enough -- Sex And Religion. It's an ambitious record that finds the seven-string axe demon matching chops with bass ace T.M. Stevens and drum virtuoso Terry Bozzio. For his vocal alter-ego, Vai chose 20-year-old Devin Townsend, a hitherto unknown singer/guitarist from Vancouver, Canada.

Having played alongside David Lee Roth and Whitesnake's David Coverdale, Vai is no stranger to manic, demonstrative lead singers. And his work producing kid rockers Bad 4 Good last year must have taught him a few lessons in how to deal with youthful high spirits in the recording studio. But no prior experience can quite prepare one for the motor-mouthed, hyperkinetic Mr. Townsend. The kid can scream like a lost soul getting its pancreas pecked out by a giant buzzard in the lowest circle of Dante's Inferno. And that's just on the ballads.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

All in all, Sex And Religion is a jolting followup to Vai's instrumental opus Passion And Warfare. Most of the songs start out squarely in hard rock/pop territory. But they soon lurch off onto some harmonically or rhythmically bizarre tangent, often propelled by Vai' s trademark, death-defying axework. "That's what I mean when I say I can't help myself," he laughs.

But then we've come to expect as much from the lanky, intense guitarist who thinks nothing of practicing 15 hours a day. When Vai was just an impressionable young junior at The Berklee School Of Music, Frank Zappa thought enough of the young guitarist's prodigious devotion to assign him the daunting task of transcribing all the intricate arrangements for Zappa's band. Vai subsequently soared to greatness, his skill and near-fanatical commitment to excellence carrying him from triumph to triumph on his chosen instrument.

Some people are victimized by their own obsessions. Vai seems to draw power from his. And as the following interview suggests, if there's anything he likes more than acting out his fascination with sex, religion and music, it's talking about them.

GUITAR WORLD: Is Sex And Religion a concept album?

Not as much as Passion And Warfare was. It's different because the new record has lyrics. With an instrumental you can go off into endless discussions about what the melody means. But when you write lyrics, it's much more straight-ahead. The concept, though, was that I wanted to do a record with a vocalist and some players with strong, identifiable styles. I wanted to do something that had definite rock elements to it but was also twisted, like the stuff I normally do.

Why did you want to work with a vocalist this time?

I've always used vocals, really, except for Passion And Warfare. It just seemed like a natural progression to return to a vocal approach. But that doesn't mean that everything I do in the future will have vocals. That's why I'll probably never be a million-selling artist -- because I'm always going to change my records. I mean, I've been working on a project for the spring of '94 that's going to be my music played by a 30-piece orchestra and a rock band. It's completely different from anything I've done before.

So each project takes on its own identity.

Yeah. The way I'm thinking now is maybe my next rock project will have no keyboards -- just bass, drums, guitar and vocals, with no overdubbing -- whereas I played a lot of keyboards on Sex And Religion.

How did you find the players for this project?

Well, I have five Hefty trash bags full of singers' tapes. They're all real cute, they all sing really well and they all write nice, safe stuff. But Devin Townsend made this tape called Noisescapes that's just the hardest core industrial, heavy metal-but-melodic music imaginable. He's 20 now, but he was just 19 when he made the tape. He sent it to my record company [Relativity] and I got it through them. As soon as I heard one minute of Devin, I knew he was someone special. We got together at my place in Tahoe. It was just me, him and my engineer Liz, rolling in the snow and jumping in my jacuzzi. He has a really great attitude. He's willing to try anything. And he's really an extrovert -- you know, a great lead singer.

As for T.M. Stevens, I saw him in Spain, playing on a TV concert with Joe Cocker. I was burning my feet on the pavement, but I wouldn't get off because I was too busy watching T.M. I always knew he could play; I just didn't know he could play so well. And he had that look that I thought could really work. And Terry Bozzio; geez, I've always wanted to work with him. He's been my favorite drummer forever. He usually doesn't like rock and roll, so it was very odd that I could get him to do this project. But he did, and I think he kicked butt.

Did Devin play guitar on the album?

No, although he's a fabulous guitar player -- very smooth, with a lot of chops and facility. He's got this sweeping thing that's really phenomenal. He's probably going to play a lot of guitar live. But for the record, I just felt better doing all the guitars myself. I just said, "Here are the songs, let me overdub everybody." Maybe in the future I'll record more live jams. But I wanted to be real careful that this album didn't turn out sounding like fusion.

In terms of technique, did this set of songs demand anything new of you?

Well, this is really the furthest possible thing from a solo guitar album, but there's a song called "Rescue Me Or Bury Me," with a big, long, meandering five-minute guitar solo [laughs]. I touched on a really weird technique there, where you hit a note, pull up on the whammy bar and then play a melody -- with the bar pulled up. Then you depress it on a strategic note and play with the bar depressed. You use the bar to reach pitches as part of a melody: you play with the bar raised and depressed. It's very difficult. You have to have stunning intonation, for one thing. What's cool about it is that you can get some note bends that sound very unnatural on guitar.

Another thing I did at the very beginning of that solo was to play with my fingers instead of a pick, which I usually don't do. And I realized that it sounds very much like Jeff Beck if you do that.

Because he plays with his fingers.

Exactly. So it wasn't hard to get Jeff Beck tones. That's something I only touched on in that song, and I'd like to explore it some more. Also on there, I do this thing where I play the same two notes on every string. [Vai demonstrates, playing a G sharp to F sharp pull-off, first on the high E string (fourth to second frets), then on the second, third, fourth and fifth strings, moving up and down the fretboard, sliding into each pull-off] When done fluently, it sounds really unnatural.

The notes are the same, but the different thickness of each string provides timbral variations.

Yeah, it's like an audible illusion. Here's another technique I used on there. [He plays a riff that involves using three different fingers in rapid succession to fret the same note: i.e., an F sharp triplet on the second fret of the high E string, played with the second, third and fourth fingers.] If it works properly you get all these weird little grace notes.

On the song "Touching Tongues," you play some very high harmonics. How were those achieved?

That's a Digitech Whammy Pedal in conjunction with a delay. You hit two notes [sings: F sharp, D sharp] and you release so that the echo takes over and creates a harmony over the next two notes. Most people get hold of a Whammy Pedal and what do they do? They grab it and go whhhheeeeeee....

The same thing they do with a whammy bar.

Yeah, but there are so many more musical things you can do.

So on that solo, are you fretting harmonics or just hitting regular notes?

Hitting regular notes. It's a very cool sound.

The overtones are celestial.

What happens is I have the Whammy pedal set to an octave or higher, so when you play a C sharp way up on the high E string and you hit that pedal, the overtones go up into the stratosphere, you know? I'm afraid it's going to break a lot of fingers, when kids try to figure it out. You can just see them doing all these wild things.

Don't try this one at home, kids.

Yeah, be careful. It's very simple in reality. That was just a very simple sound that I heard before I even plugged in the guitar. I knew exactly what it was going to do; I've been waiting a long time to use that particular effect.

You're known for using meditation to help discipline yourself in your guitar playing. Was that an element on this record?

Well, I think we all meditate. I first became aware of meditating -- I'll call it "external meditation" -- when I was transcribing for Frank Zappa. I'd find myself using a different part of my mind. When you concentrate wholly and intently on something without letting your consciousness waver, you really start to enter a new world. That would happen when I transcribed, and also when I practiced, because I would really concentrate hard on some guitar technique. When you can actually focus without distractions -- which is very difficult -- you can get the results you want. I think there were moments on this particular record that were the products of meditation.

I think that's true of any artist. I don't single myself out. But all that is just one form of meditation. The important kind of meditation, I feel, is when you take all that energy and focus it within yourself. That's believed to be so by more than half the people in the world. It's just unfortunate that this half doesn't happen to live in the United States.

Meditation is not just a means to an end for you? Like, "I can play faster guitar if I do this.... "

Oh, no, no. Music is great; I love it dearly. But that is a means to an end for me. My end is not being able to play the guitar fantastically. I mean, I know how to do that -- or at least I've briefly touched on great playing at times. But as much as guitar playing is dear to me, it's not the most important thing in life.

What would happen if I were to lose my hands? You can lose all that crap. You can go deaf, lose your eyes.... Then what? How good is your guitar playing? What do you have? You only have yourself -- your consciousness. So my next round of battle is not going to be with the guitar. It's going to be with myself and my consciousness. That's the one thing that's always with you.

Leaving metaphysics aside, Sex And Religion is a harmonically adventurous album. You seem to be using modes that one doesn't usually hear in rock and roll.

That's another thing I can't help. You're gonna hear modes in there that you never heard on any other record or any other type of music, simply because I made them up out of synthetic scales. Like the end of "Deep Down In The Pain" -- that really weird birth sequence. What's happening is that a child is coming out of the womb, you know? He's hearing the voice of divinity and asking questions and all this weird stuff. But what you hear in the background is all this wild music based on a scale I devised.

A new scale?

Yeah; I call it the "Xavian" scale. What I did was take the 12-tone row and make sampled notes of it on the keyboard. Then what I like to do is experiment with different temperaments. [Ed. Note -- The 12-note European tempered scale is only one way of dividing up the frequency range between octaves. Different systems exist in other cultures and in the work of composers like LaMonte Young and Wendy Carlos. Some modern synthesizers offer alternate temperaments.]

I have this book where I keep all these different scales, where I divided the octave up into different steps -- like maybe 9 or 10 equal steps. I call these scales "fractals." At the end of "Deep Down In The Pain" I used a scale that's based on dividing the octave into 16 equal steps, instead of the 12 steps of the conventional tempered scale. So each half-step within that is not quite a conventional half-step -- it's 60 microsteps as opposed to 100 microsteps. Instead of calling it a half-step, I call it a "quasar."

Then the "whole step" is 120 microsteps, instead of200. Instead of calling it a whole step, I call that a "nova." All these different intervals create the Xavian scale, a 10- note scale that I extracted from this 16-note row. You take this scale and play chords with it and it's like divine dissonance, because all the intervals are twisted.

Every six notes or so, you run across a tempered interval. But for the most part, these are not tempered intervals, so you get a whole structure of harmonics that is just eerie and unique. You know how every chord conjures up a different mood? Even to the most casual listener, a major ninth chord will create a different feeling than a minor ninth, or a major ninth with a sharp 11th. Imagine the twisted world of emotions you can open up from the Xavian scale! We human beings are so shaped by music in our evolution. I think that as more people get into experimenting with these fractals, a whole different emotional state of mind will result -- one that is probably on a par with the way our evolution is going anyway. But I don't think you'll ever hear Metallica jamming on the Xavian scale.

If they read this, maybe they'll get into it.

I'll lend Kirk my 16-fret guitar. You can't do this stuff on a conventional fretted instrument. I have a guitar that has 16 frets to the octave. Steve Ripley built it for me years ago. He also built me one with 24 divisions to the octave.

So you've been experimenting with this for some time?

Oh, yeah. He built me those guitars about eight years ago.

Are there any other recordings of yours with Xavian scales or the like on them?

No. But there are a couple of weird things. There's a song called "Chronic Insomnia" on Flexable Leftovers, where I recorded eight different passes of the same melody. Each time I just tweaked the tape speed a little bit, so I ended up with a melody where each note spans an entire half-step. It's a very dense, eerie-sounding thing. Incidentally, I'm probably going to be remixing Flexable Leftovers and all my other stuff from that period and putting it all onto one disc.

What's also interesting about "Still My Bleeding Heart" is that little orchestral section before the solo.

That's another thing I couldn't stop myself from doing. I've got this nice song going along. Everybody's saying, "Yeah, man, nice chorus, nice hook." So I figured I had to do something to twist it. I love the way melodies work against awkwardly moving chords. So that section is just a case of taking a melody and reharmonizing it. It goes through a progression of major ninth chords and dominant seventh/sharp fifth chords. I mean, the jazz guys have been doing stuff like that for years.

Yet you said earlier that you wanted to avoid a fusion mood.

Well, what I meant by that was that you can do bad fusion. For me, fusion is like disco: it's a certain taste. I like taking little pieces of it, because the fusion thing was a big part of my upbringing and I think there are nice little moments you can get from fusion. I think that a particular two-bar phrase in the scheme of a six-minute song works very nicely. But a whole song with all these meandering augmented ninth chords -- maybe that would be too much like fusion.

Like eating too much crème brulee.

Very well put. [laughs] Crème brulee!

I read somewhere that you do almost all your recording at night.

Well, you see how it is around here during the day -- all the phone calls and faxes and Fed Ex deliveries. Can you imagine trying to get any serious recording done with all that going on? So what I do is wake up when business hours are over and start to work. I wake up at five o'clock in the afternoon, and work around the clock until nine or 10 in the morning, when everybody else is starting to get up and go to work. This way I get a lot more done.

Just like Frank Zappa.

Yes. Well, what Frank does is work 'til he can't stand it any more, and then goes to sleep. He's always done that. I'm a little easier on myself. Your body can adjust if you stay up maybe two extra hours a night. I just kept doing that until I reached the time frame that I liked. But yeah, I saw Frank working through the night and I thought it was cool; I discovered its benefits. But it also has its drawbacks. My family is up when I'm asleep, and if you want something at four in the morning, you're in trouble, because nothing is open and nobody' s around. You gotta make sure you got all your food and everything. It's like a camping trip every day.

There's something else that you do that reminds me a little of Frank: It seems that you're always recording incidental little conversations, and things that happen around the studio, and putting them on your records.

Yeah! That was something about Frank's music that I always loved -- all those weird little things in between the songs. Maybe I did get that from Frank; I don't know. It's certainly something I was always attracted to. He does it great, though. He's the total king of that stuff.

Have you seen him recently?

Yeah, I saw him just the other day. He called me up and I went up to his house. There's an orchestra he's going to be writing for, called the Orchestre Moderne. His composition "The Yellow Shark" was performed in Vienna and Frankfurt recently; I saw three performances of it and it was really great. Now Frank wants to put them together with Terry Bozzio and me to do all of Frank's hardest material, like "Sinister Footwear" "Mo And Herb's Vacation" and all the renditions of "The Black Page," which is probably going to be one of the biggest challenges I've ever faced on guitar. But it'll be cool, because I've got my hammering a lot more together now. Playing all those weird melodies, trying to pick every note, is impossible. Hopefully, this will take place in the fall of '94. That's what we're shooting for.

Besides yourself, who is your favorite guitarist to have played with Frank Zappa?

Oh, I like Adrian Belew. He's always doing great stuff. And Denny Walley plays great slide. And although I don't know much of what Warren Cucurullo did with Frank, I just called Warren the other day because I thought what he did on the new Duran Duran record was really great. So I like those guys. Who else was there, really?

Mike Keneally.

Apart from one rehearsal, I never saw Mike with Frank. But when I saw him do Frank's stuff at the "Zappa's Universe" tribute in New York, I was pretty impressed. He does all that weird melody stuff that I did. Maybe he even does it better.

What kind of guitar tone did you have in mind for Sex And Religion?

I put a lot of research into that. The only way to really tell the way any piece of equipment sounds is to bring it into the studio, record something with it, then record it again with a competitive piece of gear on an adjacent tape track and NB them, which is what I did. I went to ridiculous lengths to compare instruments, amplifiers, microphones, strings and everything else I used on the album. I mean, I filled the room with amplifier heads. Name one -- it was in there. And all the preamps. I decided on my Marshall Heritage head for the majority of the sounds -- what I call a Heritage, anyway. It's a JCM-900. I used that mixed with the ADA MP-1 preamp. I chose a VHT power amp, which is a real workhorse, and real metal sounding. The cabinet I went with was a Marshall slant-top with 30-watt Celestions.

Did you do anything similar for guitars?

Yeah. You're gonna love this. I wanted to design a new guitar for myself and for Ibanez, based on the Jem -- because the Jem for me is the ultimate weapon. The new one was designed to satisfy my little idiosyncrasies; the way I play. [Vai disappears and returns momentarily with a white Jem-style guitar with gold hardware.] In the past, I was never concerned about things like wood or the pickups or the sound of the tremolo. But I decided to find out what all these things really contribute to the sound. I had Ibanez make me all these different guitars; I had them going crazy. We started experimenting with body wood.

Originally I had a basswood body, and I had them make me identical guitars with alder and maple bodies. I recorded all three and did the AJB test. What I noticed was that the maple was very bright. The alder is a little warmer, and that is the one I like. The basswood sounds thinner. So this is an alder body [brandishes guitar]. Then we started experimenting with necks. I found that a thicker neck usually has better resonance. But I like the way a thinner neck feels. So I just made a compromise there.

There was a lot of talk about the whammy bar -- whether it has a different sound when it's floating or when it's mounted so that you can't pull up on it. I had them make me one of each: with the exact same wood, pickups and everything. To be perfectly honest, I don't notice a difference in sustain. The big difference is in the playing. With a floating tremolo system, there's a good chance you're going to have this problem: [Illustrates how the pitch wavers due to palm pressure on the bridge]. I can't stand that. It's so hard to deal with. Plus, when you bend a note the other strings bend too. So we put this in the guitar. [Turns the guitar around to show the tremolo compartment.] There's a little device here that keeps the bar taut at a certain position; then, if you want to go sharp, you have to pull a little harder.

So you've got a separate set of smaller springs in there just for the pull ups.Yeah. And you adjust it. It's easy to tune up, because it doesn't float all over the place every time you change a string. And I can still wind the bar up -- do whatever I want with it.Did you experiment with the pickups as well?I thought you'd never ask. The first decision was whether to mount the pickups directly into the body or into the pickguard. We tried both, and I chose to have them mounted to the pickguard. It seemed to have a better bottom end that way, and better resonance. As for the pickups themselves, I'm afraid I put poor DiMarzio through hell. Oh man, poor Steve Blucher [design engineer at DiMarzio] has a few grey hairs on him that say "Vai." We designed about six different pickups that I liked, all named after Harley Davidson engines. And the ones that are in this particular guitar now I call the "Evolutions." They've got a lot of bottom end and a lot of top end. They're a little shrill, so you have to sometimes tweak the EQ on your amp, but they have a presence to them that a lot of pickups don't have.And of course you've got humbuckers in the bridge and neck positions and a single-coil in the middle position.Right. But this guitar is unique in its pickup selection. In the second position on the pickup selector, the bridge humbucker becomes a single-coil and it's on in conjunction with the middle pickup. In the fourth position it's the same thing, only with the neck pickup. So I can get that real Stratty "in-between" sound which I love but usually can't get on a humbucker guitar.Getting back to the album, what kind of unique difficulties did you encounter in writing vocal songs?I suppose the need to come up with strong pop hooks is a big one. Like that song "In My Dreams With You" -- that hooky pop chorus actually comes from a song written by a friend of mine, a guy named Roger Greenwald. He's a really good guitar player and producer. It's part of a song he wrote back when I was in college, and I've always wanted to do something with it. I basically re-wrote the whole song, structure-wise, and then got together with Desmond Child to work on the lyrics. Desmond is really a unique lyricist. A lot of people just think of him as the king of schmaltzy pop, because he made a lot of money for all these bands like Bon Jovi and Aerosmith. But he's capable of doing anything really. We worked on a few things, although "In My Dreams With You" is the only one that made it to this album.Did Devin have any input with regard to the lyrics?Yeah. We wrote "Pig" together. That's a great song. Pretty weird, eh?It's out there.You want to hear something funny? "Pig" came about because I was watching the Black Crowes on MTV one day. I like the Black Crowes. They were playing that song "Remedy," and I thought it was a great song -- a real nice party song. I said. "Man, I need a song like that: something really straight-ahead that everybody can relate to and sing along." So I went and wrote "Pig." Sorry folks, I can't help myself. Plus I was listening to Pantera at the time, which I think is an incredible band. Diamond Darrell man, he's my new favorite guitar player. He's out of his mind. He's got this totally unique, razor-blade tone. And that album is probably the loudest-mixed record in existence. And it's just a free-for-all of chaotic harmonies. I wanted to go and play with them when they came to town, but I was out of town.Who else do you dig these days?Reeves Gabrels. I saw him play with Tin Machine and it was one of the most enjoyable guitar concerts I've seen. Because he's so out there, man. He's got that really crazy, nervous vibrato. And he'd probably write something just as left-field as "Pig" if he tried to write a song like "Remedy" too.Tell me, why is the album called Sex And Religion?Oh, a lot of reasons. "Sex" and "religion" are two very powerful words. The sex of religion is like the passion of warfare. Sex in its purest form is where two individuals find an intimate relationship with God at the forefront of their consciousness, you know? It's the divine act of love. Then on the other end of the spectrum you get the perversion of lust. It goes as far as things like murder and whatnot. I think most of us fall somewhere in between.

It's the same thing with religion. The basis of religion is pure inspiration, where one individual came along and realized God and then tried to give his instructions to the world. But then that gets all twisted to suit the needs of the ego and the people involved. At the core of all religion and at the core of all sex, there's love. It's just interesting to see how that gets perverted and transformed. I mean, religion has been one of the biggest causes of war in history. I don't condemn any religion, don't get me wrong. I even think there are probably some very true evangelists out there, who are very inspired. But then there's guys out there who are trying to make money. They sell the promise of hope for money. And believe me, there's nothing so dangerous on the face of God's beautiful blue earth as a religious pervert. So anyway, I just find those two concepts very intriguing. Plus a lot of people are really hung up over sex and religion.

In a career that spans five decades, Alan di Perna has written for pretty much every magazine in the world with the word “guitar” in its title, as well as other prestigious outlets such as Rolling Stone, Billboard, Creem, Player, Classic Rock, Musician, Future Music, Keyboard, grammy.com and reverb.com. He is author of Guitar Masters: Intimate Portraits, Green Day: The Ultimate Unauthorized History and co-author of Play It Loud: An Epic History of the Sound Style and Revolution of the Electric Guitar. The latter became the inspiration for the Metropolitan Museum of Art/Rock and Roll Hall of Fame exhibition “Play It Loud: Instruments of Rock and Roll.” As a professional guitarist/keyboardist/multi-instrumentalist, Alan has worked with recording artists Brianna Lea Pruett, Fawn Wood, Brenda McMorrow, Sat Kartar and Shox Lumania.