4 soloing ideas you can learn from Leslie West

Scale the blues-rock mountain and balance on the edge of major and minor tonalities with this lesson in the style of one of rock's greatest players

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

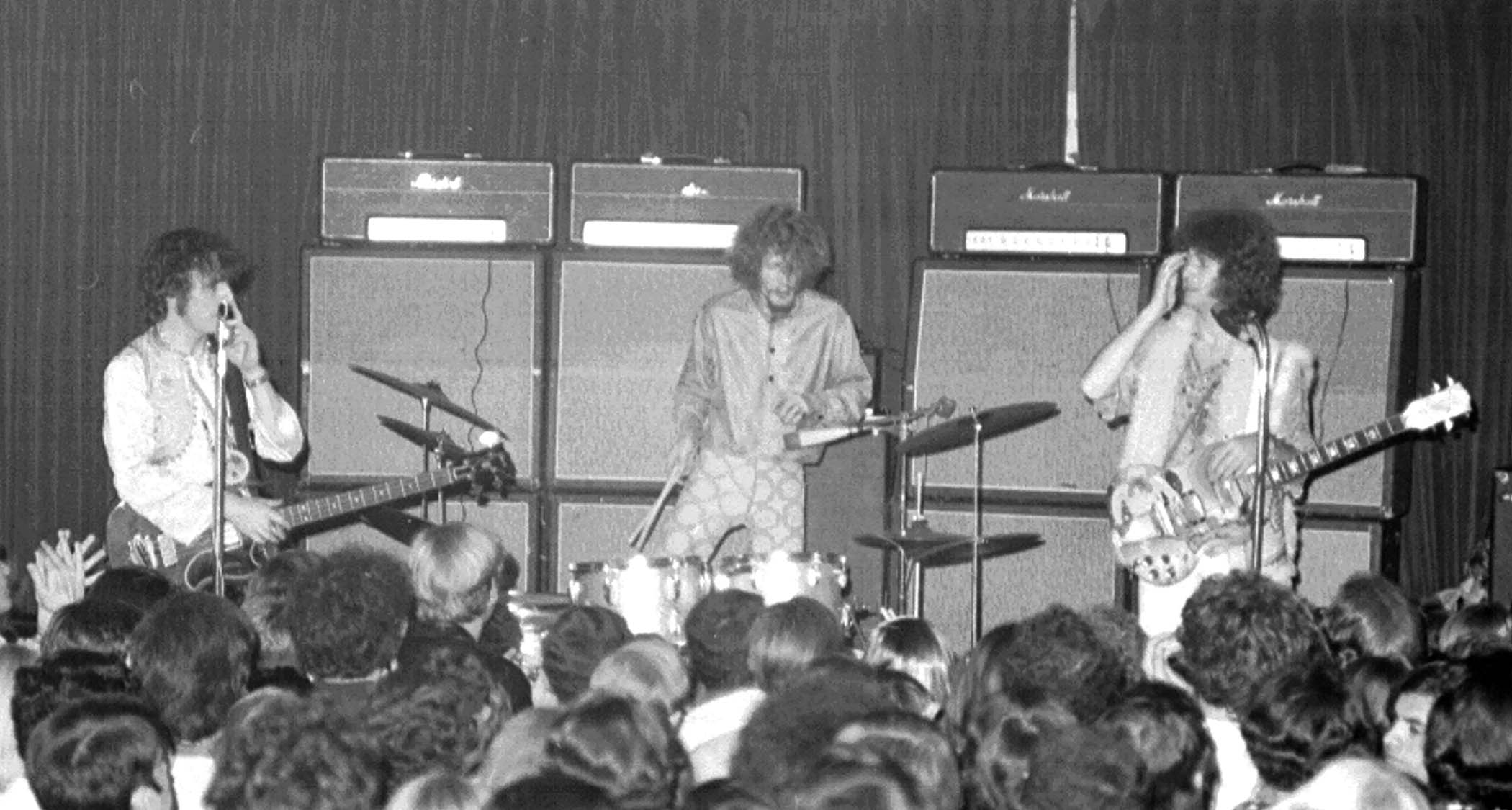

It’s hard to imagine what it must have been like hearing Leslie West tear into his set with Mountain at Woodstock in 1969. The most enduring image today is West playing his Les Paul Junior with a driven tone and sustain – which still sounds great, even at a time when such sounds have become easier to achieve and are relatively mainstream.

Rolling Stone’s suggestion back then that Mountain were a “louder version of Cream” wasn’t entirely without merit, but Mountain definitely brought their own take on blues and rock to the mix – and played through stacks of Sunn amplifiers modified for higher gain, which was pioneering thinking in itself!

Of course, Leslie West played several different guitars through a number of different rigs throughout his career, but he always managed to hit a sweet spot with his volume, drive and sustain. He favoured both major and minor pentatonic ideas in his solos, which would contrast with his frequently minor pentatonic riffs or powerchord sequences, which didn’t automatically suggest a major soloing approach.

I’ve said this before, but it’s worth repeating: blues and blues-rock gets so much of its character through the deliberate contrasting of major and minor ideas, whether that’s B.B. King pulling a minor 3rd slightly sharp, or Fats Domino trilling between a major and minor 3rd on the piano to give the illusion of a note somewhere in between.

I can’t pretend I’ve second-guessed exactly what Leslie West would have played over this backing, but it’s certainly been fun to check out a few of his performances over the years and take an educated guess.

As you’ll see, the solo was originally played as one continuous take, but we’ve broken it up into four sections to make it easier to digest.

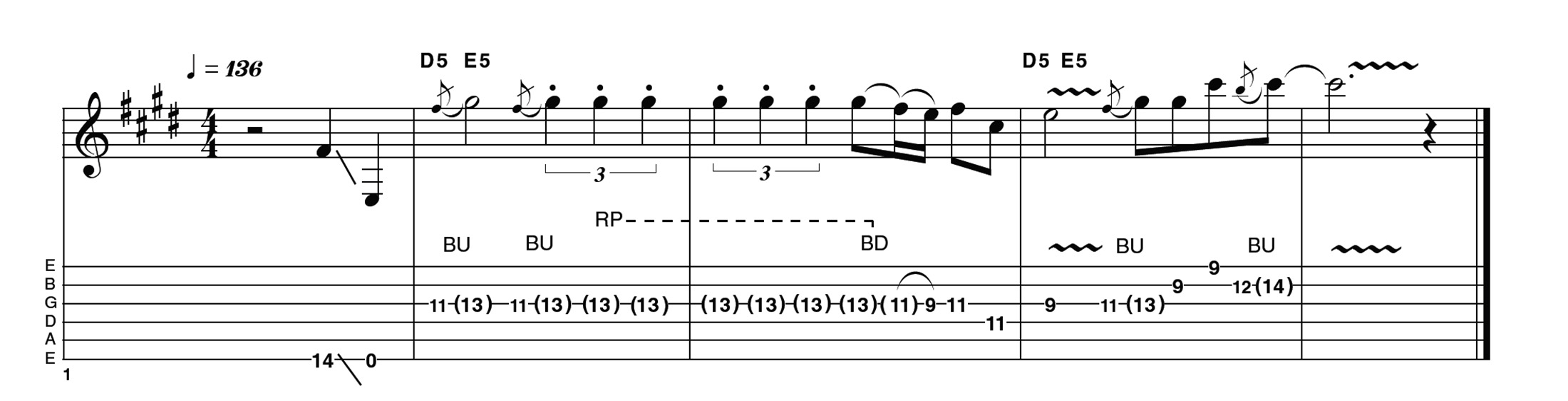

Example 1.

This opening phrase heads straight for the major 3rd (G# in this key of E). There’s a stuttering rhythm here before heading to a more conventional pentatonic phrase.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You could regard this as a shape 5 E major pentatonic or a shape 1 C# minor pentatonic, as they’re exactly the same thing, albeit with a different root note. As you may know, every major key has a relative minor, which can be very useful when you want solos to sound ‘bluesy’ in a major key.

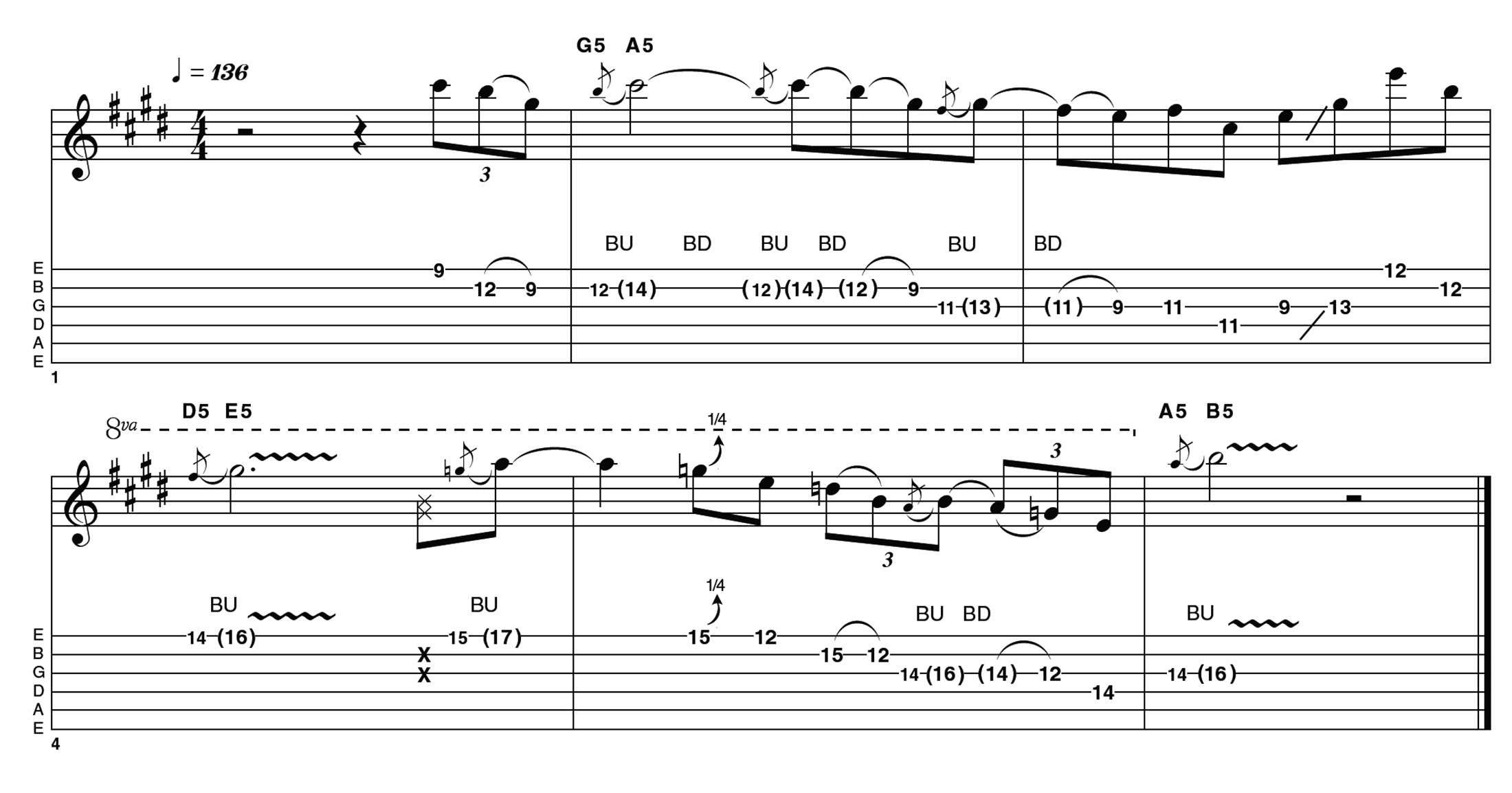

Example 2.

As we continue, we’re still using the E major/C# minor pentatonic in the 9th position, shortly moving up to the 12th fret for what I like to think of as a shape 1 E minor pentatonic, but acknowledging the major 3rd (G#) by bending all or part of the way to it, as well as playing it outright. This is where all the action is when looking to create that major/minor ambiguity that so characterises the blues.

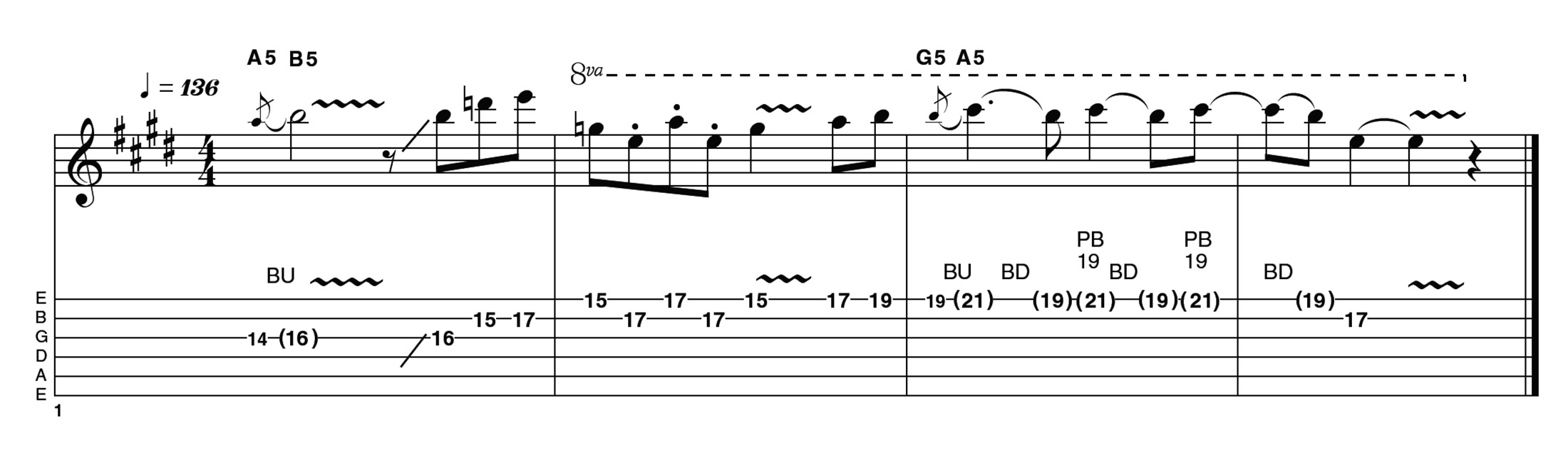

Example 3.

Almost immediately, there is another shift upwards, still staying pentatonic. We start with a fairly clear demonstration of a shape 2 in E minor on the highest three strings, then slide up for what is basically a shape 3 of that same scale but bending up to a C# at the 19th fret of the high E. This nails the major 3rd of the A chord underneath – a powerchord with no 3rd but now perceived as major!

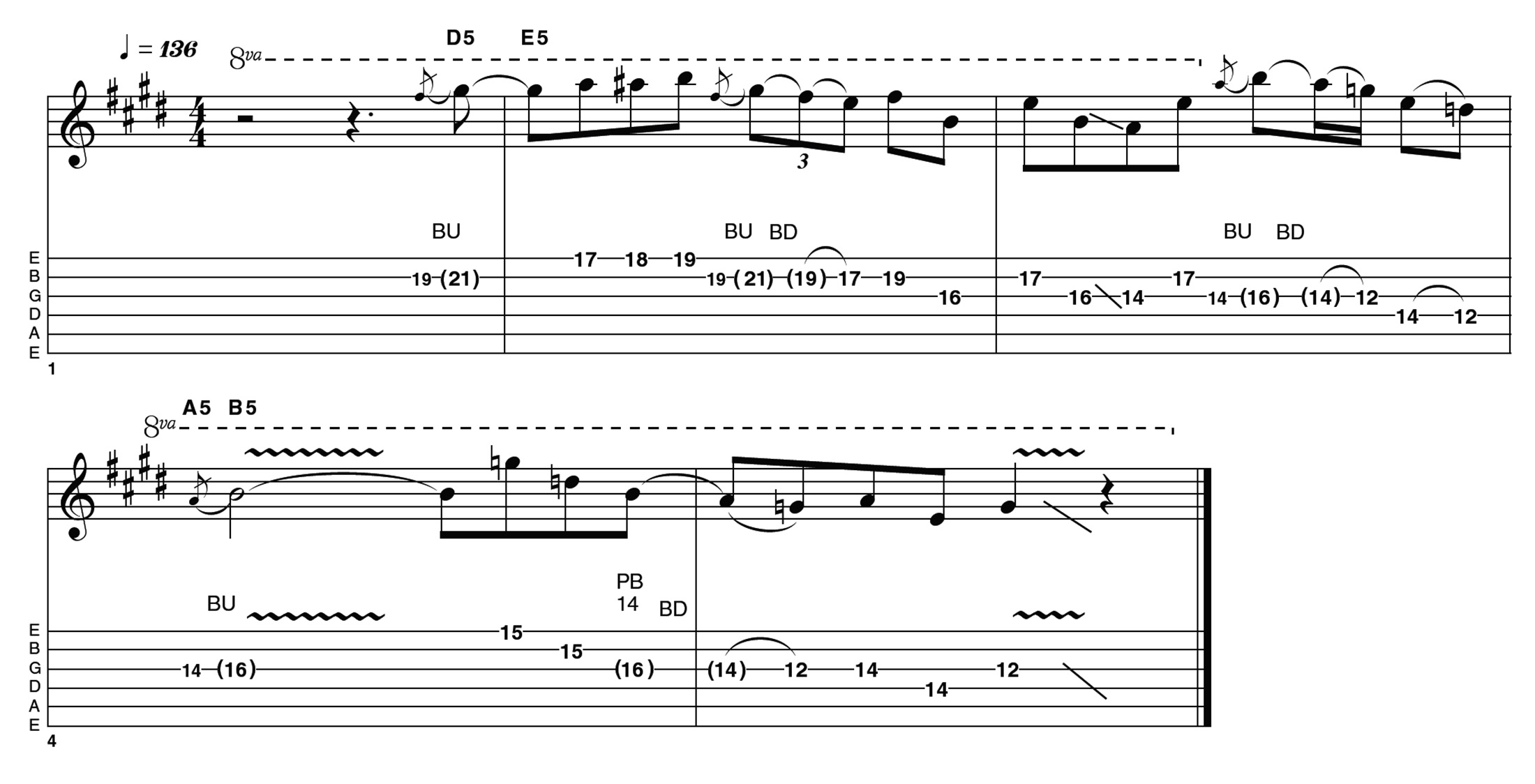

Example 4.

Staying in the same position over the change back to E and incorporating a number of bends into the major 3rd (G#), I still prefer to view this as E minor pentatonic with some bends to G#.

However, you could also correctly view this as a shape 3 E major pentatonic. Either way, we soon shift/slide down to a clear case of shape 1 E minor pentatonic. Go with whichever way works best for you in the moment.

As well as a longtime contributor to Guitarist and Guitar Techniques, Richard is Tony Hadley’s longstanding guitarist, and has worked with everyone from Roger Daltrey to Ronan Keating.