Allan Holdsworth: 5 game-changing guitar approaches you can learn

He's been heralded by the likes of Steve Vai as the greatest guitarist who ever lived – here's how you can incorporate the fusion master's innovative approach to the instrument in your own playing

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

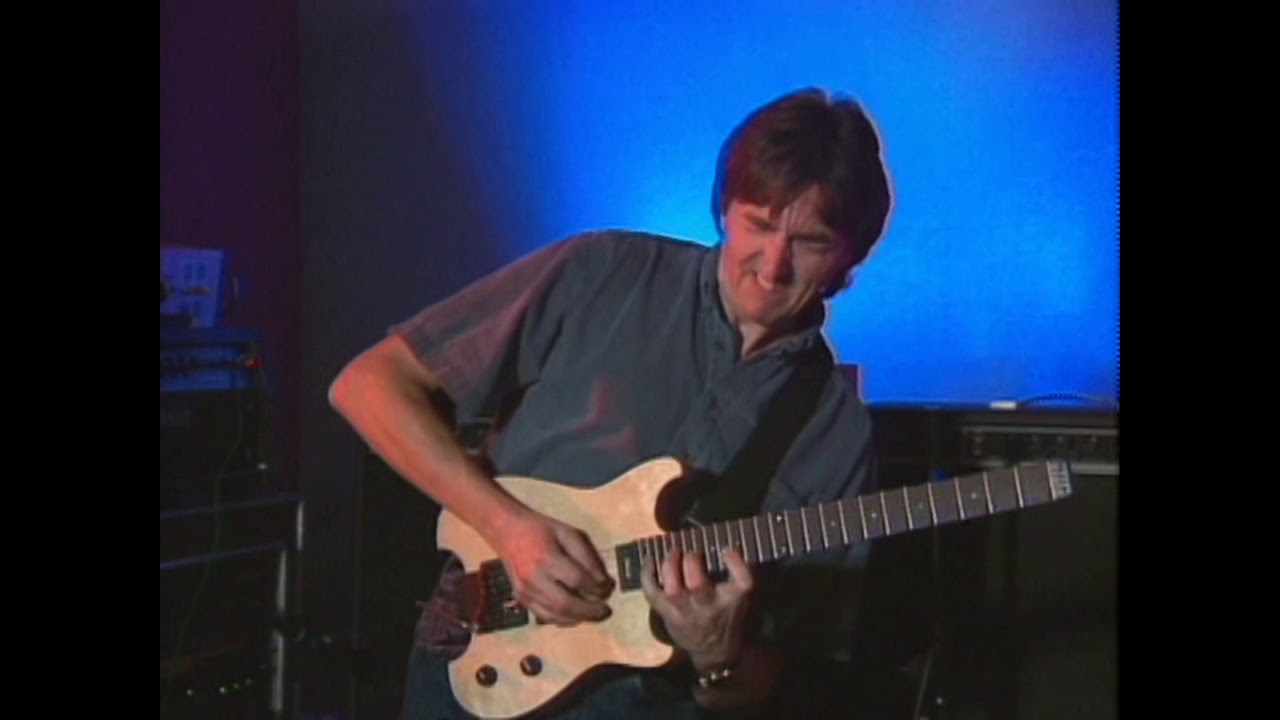

Allan Holdsworth’s playing was simply staggering. He had access to an immensely sophisticated harmonic, rhythmic and melodic vocabulary that was steeped in the tradition of jazz and also assimilated elements of rock, fusion, funk, blues and even classical harmony, but the end result was undeniably his own.

Allan was a special artist indeed, with a unique approach to music and one of the most recognisable sounds in guitar from the late ’60s until his passing on 15th April 2017.

Born 1946 in Bradford, Yorkshire, it’s widely known that Holdsworth didn’t really ever want to play the guitar, preferring the sound of the saxophone but when practical considerations got in the way (his parents couldn’t afford one!) he turned his attentions to the guitar, albeit without the intrinsic connection to the idiomatic vocabulary of this instrument.

Holdsworth’s father was an accomplished pianist and encouraged him to practise, but with remarkable discipline and focus Allan set about learning to play entirely by himself.

While influenced by the music that surrounded him and from hearing diverse artists in his father’s record collection, such as the legendary tenor saxophonist John Coltrane and the French classical composer, Claude Debussy, Allan set out with a steely determination to sound entirely like himself. So he worked out a highly personal approach to creating music, with both improvisation and harmony at the core of his sound and style.

Allan’s career began in top 40 covers bands, before moving on to work with progressive/jazz crossover groups such as Tempest, Igginbottom’s Wrench and Gong, and then on to touring and recording with artists such as Soft Machine, Jean-Luc Ponty, Bill Bruford and Tony Williams.

With a flair for composition, this naturally led on to Holdsworth developing an impressive career as a bandleader in his own right, with each new release eagerly awaited by his international legion of devoted fans, with live performances attaining almost mythical status.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

I’d urge you to devote some time to listening to his playing if you’re not familiar with his music, firstly to bask in the sheer beauty, but then to allow the realisation of the possibilities available, should you strive to attain this level of fluency, sophistication and articulation.

The purpose of this article is twofold: to shine a light on Allan’s genius and introduce his music to anyone who might not be familiar with it. Secondly, we’re going to explore how you can take specific concepts, for our purposes here we’re looking at five in all, and apply these ideas to your own playing.

We’ll do this by initially looking at a concept derived from Allan’s playing and then we’ll explore how the same idea has been exploited in more classic blues and jazz styles, including a host of well-known players from both of these idioms.

While learning these lines will definitely expand your harmonic, melodic and rhythmic horizons, you should then consider inventing some ideas of your own that take each concept or idea and run with it.

The end result can be as close or as far away from the initial inspiration. What’s important is that you explore the possibilities that this process has to offer, and I’m certain that Allan would approve. As always, enjoy…

Technique focus: Choose your influences carefully

While it’s undeniable that Allan Holdsworth achieved a unique and instantly recognisable voice as a musician, guitarist, composer and improviser, there were two names he consistently acknowledged as having a profound impact upon his musicianship and artistry.

These were the French composer Claude Debussy, and specifically the piece Clair De Lune from Suite Bergamasque, along with the jazz saxophonist John Coltrane, again specifically highlighting the album Coltrane’s Sound (Atlantic 1960) as being of particular significance.

Consider how you might integrate ideas from the musicians that inspire you. While this could be a specific idea, concept or musical approach, it’s equally valid to attempt to adopt a similar mind-set

While there might not be an obvious connection between the two, you can hear both of these influences clearly in Allan’s music. The beautiful impressionistic harmonic motion of Debussy, coupled with the rhythmic density and melodic intensity of Coltrane present in Holdsworth’s sound makes complete sense once you understand the significance that hearing this music had upon Allan, assimilating the essence but without ever sounding like a pale imitation of the source.

Consider how you might integrate ideas from the musicians that inspire you. While this could be a specific idea, concept or musical approach, it’s equally valid to attempt to adopt a similar mind-set, feeling or any other relevant artistic expression of intent, and attempt to incorporate this into your sound.

Get the tone

Amp Settings: Gain 7, Bass 6, Middle 5, Treble 5, Reverb

The fluidity of Holdsworth’s tone was partly a product of his accurate legato technique; too much distortion adversely affects dynamics and changes the vowel sound of a sustaining note. His clean sound was super-clean, with modulation, reverb and multiple delays.

Our virtual guitar amp settings reflect his lead settings, although gain levels with vary dependent upon the output of your pickups and the gain structure of your amp/simulator.

Example 1. Oblique motion

Our first example introduces the concept of oblique motion, where one event remains static while movement occurs in the neighbouring notes.

For our Allan-inspired idea there is a consistent C note for every chord voicing, while the surrounding voices generally move in parallel, either in step-wise scalar motion or in semitone one-fret leaps. Bars 2 and 3 are of particular interest here as they outline how Holdsworth often treats simple Major and Minor triads.

Maintaining the static C note, we see how Eric Clapton might interpret ideas from early blues players like Robert Johnson, and again keeping C as our static pivot point we see a similar idea expressed by gypsy jazz guitarist Biréli Lagrène to create a perfect intro or outro in the key of C.

Example 2. Parallel motion

Next up we’re exploring parallel motion within our chord forms. Holdsworth often created voicings by combining specific interval stacks coming from a particular host scale. He considered these from the parent scale, rather than identifying each shape as a unique chord or harmonic event.

Here we see how he might harmonise the D Dorian mode (or Dx, using Allan’s system of chord symbols), using an intervallic pattern of 7th, 2nd and 6th from low to high. Again, we see similar expressions of this idea from the blues master Robben Ford and the soul, blues and jazz sensation Cornell Dupree.

You can hear a similar harmonisation device employed in the tenor/alto/trumpet section of Miles Davis, John Coltrane and Julian Adderley on their famous album, Kind of Blue.

Example 3. Chromatic decoration

Allan was exceptionally good at filling in the gaps between chord tones and the less stable dissonances that are found nestling in the cracks between them. Our first line here outlines B Dorian over E (Bx/E).

Rhythmic intent, along with the selection of an ultimate strong resolution plays a big part in the success of lines of this nature. Resist the temptation to rush, as this will sound much less convincing.

As with the previous examples we are exploring this chromatic decoration concept from a blues and jazz perspective by looking at lines inspired by Jimi Hendrix and Jimmie Rainey respectively.

Example 4. Outside lines

This line is harmonically ambiguous right from the start, with clear evidence of Major 3rds (A) and even a chromatically approached F7b5b9 arpeggio (F-A-Cb-Eb-Gb). Holdsworth was clearly at home with harmonic ambiguity and liked to combine ideas with both Major and Minor 3rds, along with Major and flattened 7ths.

We delve into these outside ideas with a Gary Moore-inspired pentatonic pattern that moves in and out of tonality via ascending and descending semitones, and we end this example by illustrating how Pat Metheny weaves in and out of tonality by shifting small pieces of a phrase in semitones to create a propulsive sense of tension and release – an important device in both jazz and blues.

Example 5. Mixing rhythms

Holdsworth’s time-feel was wonderfully fluid and he frequently mixed up rhythmic groupings, completely spontaneously and no doubt without a care in the world.

If you’re new to quintuplets (five notes per beat) you might wish to use words to assist you here, so bar 1 could be rhythmically interpreted as ‘university-2e&a-university-4e&a’.

Our Eric Johnson pentatonic phrase shifts between triplets (three notes per beat), 16th notes/semiquavers (fours) and quintuplets (fives) to produce a forward moving sense of developing intensity. The final Adrien Moignard phrase again mixes these rhythmic units but like our Holdsworth line, he shifts freely between these subdivisions at will.

John is Head of Guitar at BIMM London and a visiting lecturer for the University of West London (London College of Music) and Chester University. He's performed with artists including Billy Cobham (Miles Davis), John Williams, Frank Gambale (Chick Corea) and Carl Verheyen (Supertramp), and toured the world with John Jorgenson and Carl Palmer.