Building Eighth- and 16th-Note Rock Rhythms

Add a ton of variety to your rhythm riffs with a fairly small amount of guitar music theory.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The music we listen to (at least in the western part of the world) conditions us, as guitar players, to a default timing and rhythm. In most cases that timing is 4/4 or what we call “common time.” Common time often shows up as four quarter notes in a measure.

However, we don’t always have to play only quarter notes when we’re in 4/4 time. And while it might be an easy habit to form, it’s dreadfully boring.

A far better alternative is to keep our 4/4 time signature and break parts of our riff down into eighth and even 16th notes for a more interesting and dynamic rhythm. We’ll cover a few detailed examples of how to add a ton of variety to your rhythm riffs with a fairly small amount of guitar music theory.

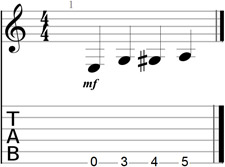

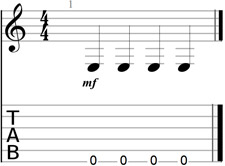

Start with a quarter note measure in 4/4 time.

Quarter notes in a measure with a 4/4 time signature.

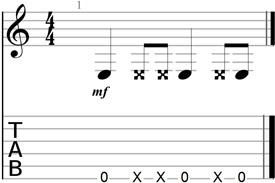

- We add a palm mute designation to give us a more rhythmic line.

- The P.M. tag indicates a palm-muted note.

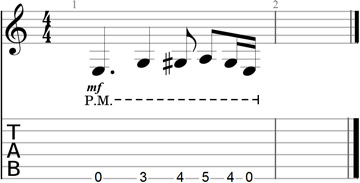

We can now make a few more significant changes.

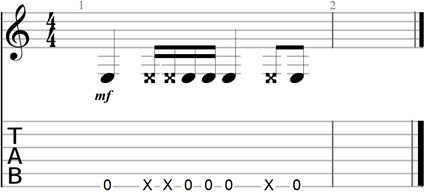

First, the initial low E becomes a dotted quarter note. We also climb up to the A at the fifth fret, then back down to the G with eighth and16th notes.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

We now have two quarter notes, two eighth notes and two 16th notes.

The result is a far more rhythmically intricate measure that uses the exact same fretboard path.

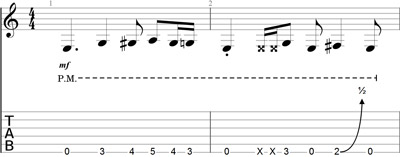

Let’s continue into the second measure.

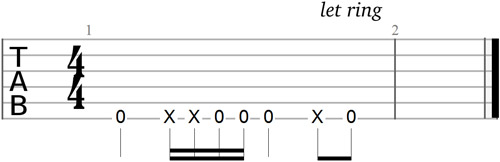

We’ve now used four total 16th notes: Two in the first measure and two in the second. The second measure continues the string muting and adds some bending for a little more variety.

There are now three total eighth notes: One in the first measure and two in the second.

Notice how we’ve continued to make a more intriguing and dynamic riff from the same four notes we started with. By using dotted quarter, eighth and 16th notes, we’ve got a lot of different possible combinations to work with that could give the original riff a lot more life.

Let’s try to do the same thing using nothing but the low E string.

Developing Eighth- and 16th-Note Rhythms with One Note

Tool’s guitarist, Adam Jones, is a master of this technique. Often in drop D, his rhythm playing tends to be far more dynamic and intriguing then what he does on melody lines, employing long runs of open D riffs comprised of just one or two notes. Relevant examples would include “The Grudge” and “Jambi.”

Here, we’ll do something similar. You can use a standard tuning or drop D for this if you’d like (the audio is in drop D).

Start with the same quarter note arrangement.

As we did before, we’ll use a combination of eighth and 16th notes to develope a more distinct rhythm line.

Let’s start with just the eighth notes and something easy.

Now, let’s do a similar line, but with a 16th note run to give a more fast-pace feel.

If you’re going to plot notes like this in standard notation, the biggest challenge is to find a way to make sure the rhythm is properly represented within each measure. In other words, you can’t technically have nine eighth notes in a single bar of music.

The tab sheet, without standard notation, is a little easier to write out, though Guitar Pro 6 (the software I used for these graphics) still adds bars and ties to indicate note type.

Learn the theory first (the difference between a quarter, eighth and 16th note) then you’ll be able to apply it to your riff-building without always having to track or write stuff down.

If you know the difference between them, it’ll allow you to create a lot more rhythm and music with a single note, which becomes particularly useful in the modern rock spaces and genres.

Some current masters of this technique would include the following:

• Adam Jones (Tool)

• Dan Donegan (Disturbed)

• James Shaffer and Brian Welch (Korn)

• Tony Rombola (Godsmack)

• Billy Howerdel (A Perfect Circle)

These guys all know how to create a lot of heavily rhythmic music with just a few notes, and in most cases they’re doing it using a combination of quarter-, eighth- and 16th-note riffs. Exact application will depend on time signature and the bpm of a given song.

For example, a lot of Tool’s music is played in 6/8 instead of 4/4, giving Jones’ riffs an entirely different (and more complex) dynamic. And while the goal is not to needlessly complicate your playing, you should be able to understand how a variety of note timing can make your rhythm playing more engaging and fun to listen to.

Knowing a little bit of music theory can go a long way.

Bobby Kittleberger is the founder and editor of Guitar Chalk, a GuitarWorld.com contributor and author of the Music Theory for Guitar Players in Plain English. You can get in touch with him via Twitter.

Bobby is the founder of Guitar Chalk, and responsible for developing most of its content. He has worked with leading guitar industry companies including Sweetwater, Ultimate Guitar, Seymour Duncan, PRS, and many others.