In Deep with Blues Masters John Lee Hooker and Lightnin' Hopkins

Take a look at the guitar work of two essential early blues masters.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The blues is ripe for endless and constant reinvention. Through the decades, it has developed in many different incarnations.

These include plantation field hollers; the acoustic guitar playing and songwriting mastery of Charlie Patton, Blind Blake, Blind Lemon Jefferson, Blind Willie McTell and Robert Johnson; the Chicago, Memphis and Texas blues of Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf and T-Bone Walker; and the mid-to-late-Sixties blues-rock revolution spearheaded by Cream and the Jimi Hendrix Experience.

Today, bands such as the North Mississippi All-Stars, the Black Keys and Alabama Shakes continue to explore new ways to navigate the dark, swampy sounds honed through this long tradition of blues interpretation. In this edition of In Deep, we’ll be taking a look at the guitar work of two essential early blues guitar masters: John Lee Hooker and Lightnin’ Hopkins.

John Lee Hooker was born in 1917 in Coahoma County, Mississippi, and learned to play guitar from his stepfather, Willie Moore, who, conveniently for John Lee, was friends with Blind Lemon Jefferson and Charlie Patton. Hooker went on the road at age 14, joining legendary bluesman Robert Nighthawk in Memphis.

In 1948, Hooker began his recording career in style, cutting two incredible tunes—“Boogie Chillen’ ” and “Sally Mae”—at his first sessions, cut in Detroit. The songs were released on the Modern label, owned by the Bihari Brothers (who also recorded B.B. King’s earliest sides), and Hooker’s ascent to blues superstardom was underway.

Hooker performed and recorded a great many tunes on both acoustic and electric guitar in open A tuning (low to high, E A E A C# E), oftentimes using a capo at the first, second or third fret to perform in different keys. He picked with his fingers, primarily using his thumb to strike the bass strings and index finger to pluck the higher strings, and achieved a warm and very percussive sound, often performing alone or with another guitarist for accompaniment.

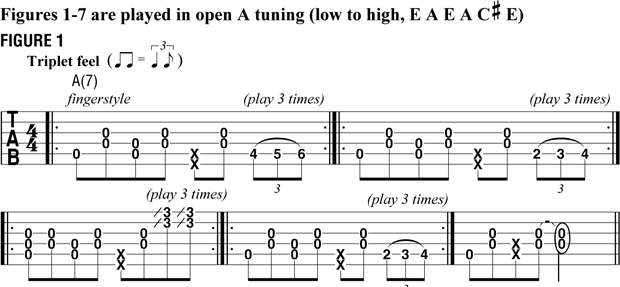

FIGURE 1 illustrates a rhythm figure along the lines of “Boogie Chillen’.” Though written in 4/4, this figure is played with a triplet, or swing-eighths, feel, which means that notes indicated as pairs of eighth notes are actually sounded as a quarter note followed by an eighth note within a triplet bracket.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Throughout this passage, the thumb and index finger alternate striking the lower and higher strings, with a quick, rolling double hammer-on occurring at the end of each bar. In bar 1, the hammer-on begins on the fourth fret and moves chromatically (one fret at a time) up to the sixth fret. In bar 2, the hammer-on starts on the second fret and moves up chromatically to the fourth fret. In bar 3, rapid slides up to the third fret are executed with an index-finger barre across the top two strings.

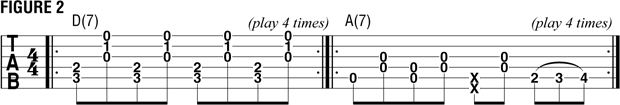

One of the fascinating aspects of Hooker’s open A playing was that he often used only two primary chords, the “I” (one) and the “IV” (four), forgoing the use of a “V” (five) chord that is common to the majority of blues music. In open A tuning, Hooker would use a standard C “cowboy” chord grip as his four chord, which yields an unusual Dadd9/C sound, as illustrated in FIGURE 2.

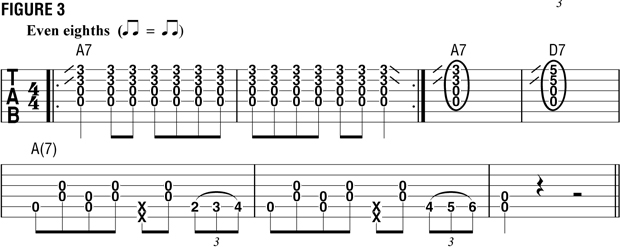

Another interesting aspect of Hooker’s solo work is that he would often shift from a swinging triplet feel to the use of even, or “straight,” eighth notes, which provides great rhythmic contrast and tension. As shown in FIGURE 3, I begin with straight eighths on a sliding A7 chord voicing and then move back to the swinging feel when the initial riff is restated in bars 5–7.

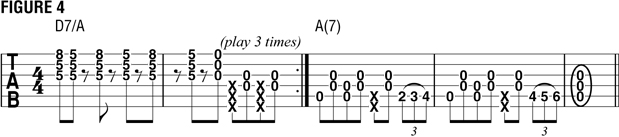

Hooker also often used the D7/A voicing shown in FIGURE 4 for his four chord: with the index finger barred across the top three strings at the fifth fret, the pinkie is added and removed from the high E string’s eighth fret. Robert Johnson often used this pattern to great effect as well.

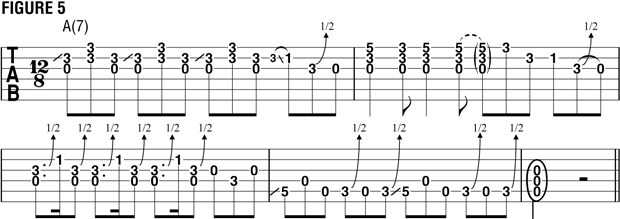

Hooker devised some great and very distinct licks in open A tuning, a few of which are presented in FIGURE 5. Following index-finger slides on the top two strings, different A and A7 voicings are followed by great single-note and double-stop licks played on the middle strings using a bit of rhythmic syncopation. You can hear Hooker play riffs like these on his classic song “Sally Mae.” ZZ Top’s Billy Gibbons is a Hooker fanatic, and you can hear many of these kinds of licks on Top classics like “La Grange” and “Jesus Just Left Chicago.”

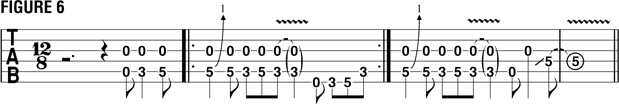

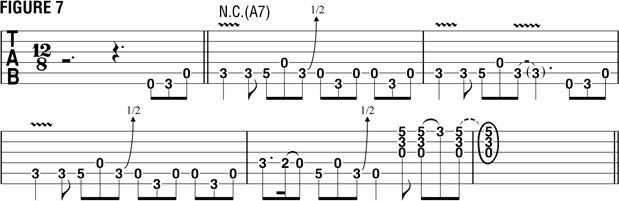

Combining open strings with single-note riffs is a central element of Hooker’s style, made more effective with fingerpicking. FIGURE 6, inspired by “Crawling Kingsnake,” and FIGURE 7, a nod to “Tease Me,” offer a few more examples of how Hooker would combine a catchy melody with an insistent root-note, open-string pedal tone.

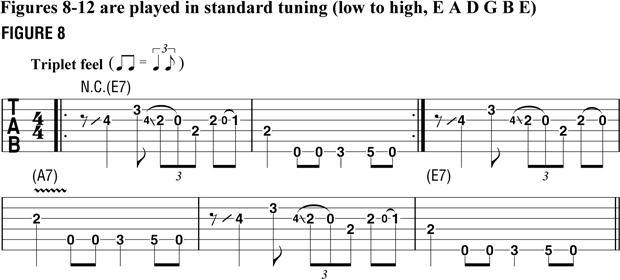

In later years, Hooker relied more often on standard tuning, while still using the capo on the first few frets for changing keys. A great example of his playing style in standard tuning can be heard on “Boom Boom Out Go the Lights.” FIGURE 8 offers an example in this style, marrying a repeated melody, based on E minor pentatonic (E G A B D) to an alternating bass line.

Lightnin’ Hopkins was born in 1912 in Centerville, Texas. Like Hooker, he learned directly from encounters with Blind Lemon Jefferson. He began his recording career in 1946 and went on to become one of the most influential blues guitarists ever. Elements of his style are clear in the playing of Jimi Hendrix, Eric Clapton, Jimmy Page, Jeff Beck, Stevie Ray Vaughan and just about everyone that played or plays blues guitar.

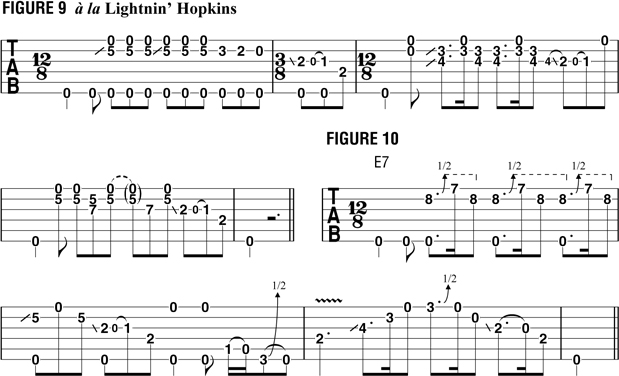

Hopkins often performed unaccompanied acoustic guitar (or amplified acoustic), picking with his fingers in a manner similar to Hooker but with the use of a thumb pick. FIGURES 9 and 10 offer examples of a mid-tempo swinging 12/8 blues played in his style, akin to his take on the blues classic “Goin’ Down Slow.”

Guitar World Associate Editor Andy Aledort is recognized worldwide for his vast contributions to guitar instruction, via his many best-selling instructional DVDs, transcription books and online lessons. Andy is a regular contributor to Guitar World and Truefire, and has toured with Dickey Betts of the Allman Brothers, as well as participating in several Jimi Hendrix Tribute Tours.