Guitar 101: Learning Harmony Through Six-Note Hexatonic Scales, Part 4

Over the past three columns we’ve looked at several cool-sounding hexatonic (six-note) scales and learned how to create new ones by combining two triads (three-note chords) that don’t duplicate any notes. Now I’d like to show you an easy way to transpose your favorite hexatonic scales to different keys and get more musical mileage out of them by viewing them from different harmonic perspectives.

As you recall from our last three lessons, the E major hexatonic or “gospel” scale (E F# G# A B C#) is formed by combining E major (E G# B) and F# minor (F# A C#) triads. In the key of E, these two triads would be considered “one major” and “two minor,” respectively. To transpose this scale to another key, all you need to do is take the major triad built upon the root note, or letter name, of that key and combine it with a minor triad a whole step above the root. This may seem like a lot to remember at first, but with a little practice you’ll soon get the hang of it and find it to be a very straightforward and useful formula that’s easy to understand and, more, importantly, to hear (remember, ear training is everything!).

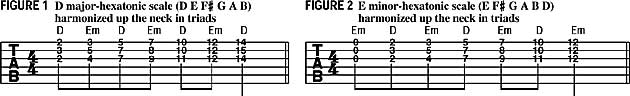

FIGURE 1 illustrates the D major hexatonic scale played up the neck in three-part harmony in the key of D. As you can see, all we’re doing here is taking the major triad built upon the keynote, D (D F# A), and alternating/combining it with a minor triad one whole step above (Em: E G B) to form the six-note D major hexatonic scale (D E F# G A B). (To hear the scale in isolation, play the notes on the second string only.)

These same two triads, D and Em, also happen to form another cool hexatonic scale, the somber-sounding E minor hexatonic (E F# G A B D) shown in FIGURE 2. When played over an E bass note, the Em triad is heard as “one minor,” and D becomes “flat-seven major.” These two scales—D major hexatonic and E minor hexatonic—are comprised of the same exact set of notes and are thus considered relative modes.

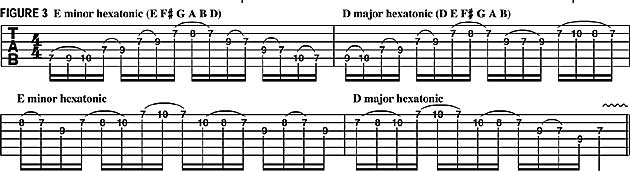

Now let’s look at some interesting things you can do with these two relative scales/modes. FIGURE 3 is a flowing 16th-note run that alternates between E minor hexatonic and D major hexatonic in a single position using the same handful of notes. Though each scale/mode can stand on its own as a tonality, notice the satisfying feeling of harmonic tension and release that’s created as the implied tonal center shifts back and forth between E minor and D major.

Another easy way to remember the minor hexatonic scale is to think of it as a minor pentatonic with an added second/ninth. The major hexatonic scale can be thought of as the major pentatonic with the fourth added.

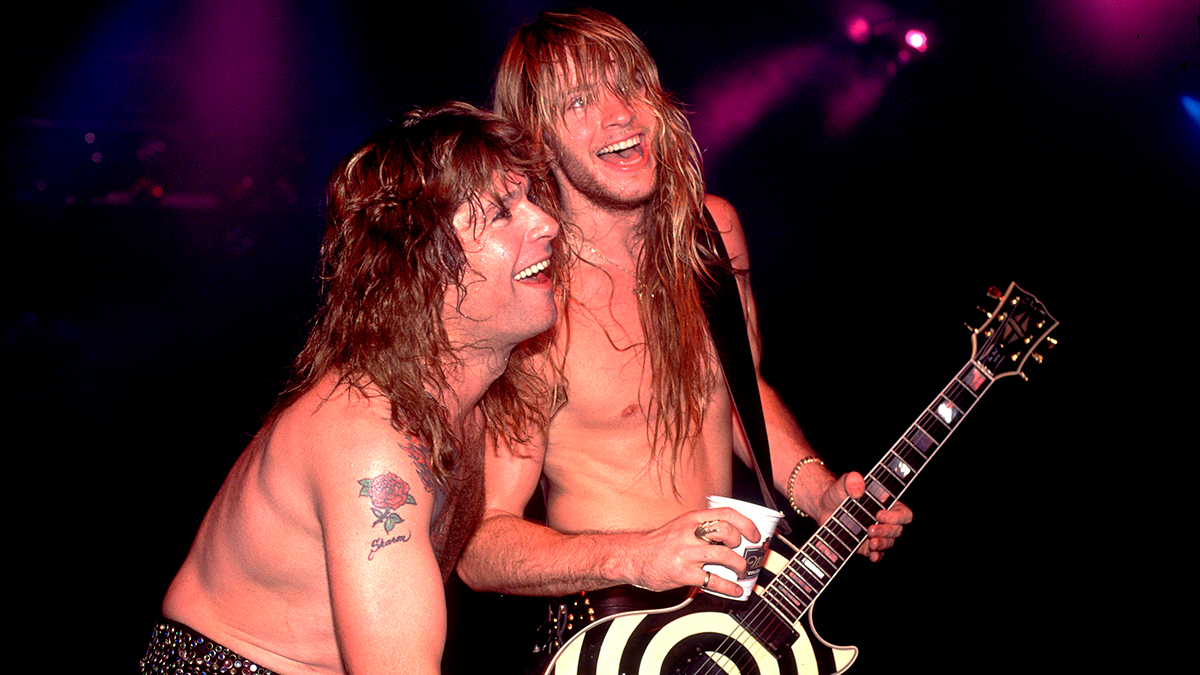

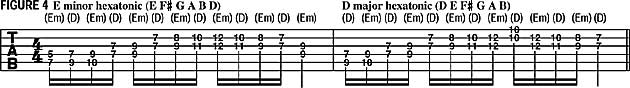

FIGURE 4 illustrates how the minor hexatonic and major hexatonic scales provide an easy blueprint for creating pleasing harmonized lead lines in a minor or major setting. Notice as you ascend each scale how the notes pair together in minor thirds, major thirds or perfect fourths. Of course, the notes will sound sweeter if played by two separate guitars, one playing the upper harmony and another taking the lower part. You can hear this kind of two-part lead guitar harmony in many songs by Southern rock bands, as epitomized by the Allman Brothers Band on such songs as “Revival,” “Les Breres in A Minor” and “Jessica.” The darker-sounding minor hexatonic scale is popular among heavy metal acts like Metallica and, most notably, Black Sabbath, as heard on their classic tunes “War Pigs” and “Paranoid.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

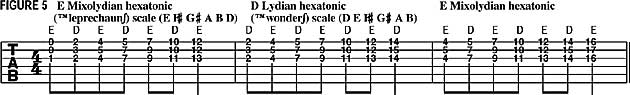

Modal relativity works with other hexatonic scales as well, as FIGURE 5 demonstrates. Here we’ve taken the E Mixolydian hexatonic (“leprechaun”) scale from last month and flipped the musical coin to show its other identity, the D Lydian hexatonic (“wonder”) scale. As you can see, both scales are comprised of E major (E G# B) and D major (D F# A) triads. The only difference is the way the notes are oriented: over an implied tonal center of E, the E triad is perceived as “one major” and D as “flat-seven major,” while over an implied D tonality, the D triad sounds like “one major” and E is heard as “two major.”

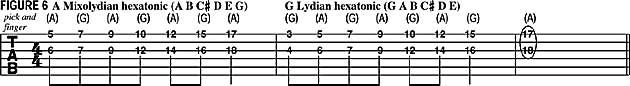

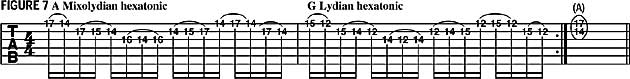

As an exercise, let’s look at another pair of relative hexatonic scales in an equally guitar-friendly set of keys, A and G. FIGURE 6 depicts the A Mixolydian hexatonic scale (A B C# D E G) and its genetically identical cousin, the G Lydian hexatonic scale (G A B C# D E), played up the neck in two-part harmony on the first and third strings. Both scales are formed by combining A major (A C# E) and G major (G B D) triads. FIGURE 7 is a fun little melodic run that uses these same two scales. The modality of the last two examples brings to mind a few well-known pop songs, namely “Jane Says” by Jane’s Addiction, “Reelin’ in the Years” by Steely Dan and “Two Tickets to Paradise” by Eddie Money, all of which are in the key of A.

The formula for the Mixolydian hexatonic scale may be remembered two different ways: as the “one major” and “flat-seven” major triads combined, or as the major pentatonic scale with the flatted-seventh added. Likewise, the Lydian hexatonic scale can be derived by combining the “one major” and “two major” triads of whatever key you’re in, or by taking the major pentatonic scale and adding the sharped-fourth.

Over the past 30 years, Jimmy Brown has built a reputation as one of the world's finest music educators, through his work as a transcriber and Senior Music Editor for Guitar World magazine and Lessons Editor for its sister publication, Guitar Player. In addition to these roles, Jimmy is also a busy working musician, performing regularly in the greater New York City area. Jimmy earned a Bachelor of Music degree in Jazz Studies and Performance and Music Management from William Paterson University in 1989. He is also an experienced private guitar teacher and an accomplished writer.