How "Free Exploration" Can Inspire New Compositional Creations

Hone in on your toolbox and develop gestures and sounds that represent what is unique about you as a guitarist.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Free improvisation on the guitar is a concept I'm fascinated with. This is a vast subject, but speaking about it within the context of this column, I’d like to discuss its importance to me and also demonstrate some methods for how I might discover new musical concepts via this tenet.

The concept of free exploration as a means of playing the guitar is something that I discovered when I was quite young, but for many years I didn’t understand how it could fit into my musical life as a guitarist. There are so many specific things to address: what to practice, songs to learn, things you need to be able to deliver when you are hired to play, the things the teacher wants you to do, composing new music, and then… free playing. Is free playing just a means of getting something off your chest, or is it really an important part of your musical personality, or your musical pursuits?

In recent years, I’ve started playing with musicians who shined a light on this concept, like Nels Cline, John Zorn, Marc Ribot — all people who have found their own distinct style when they improvise. I grew up thinking that improvising in a “free” fashion, à la Ornette Coleman or Cecil Taylor, meant that you abandoned everything, and did not realize that, like all playing, you actually can develop a vocabulary that grows from a “free” concept. You can hone in on your toolbox and develop gestures and sounds that represent what is unique about you.

When we take away the normal constructs of harmony, rhythmic constraints, melodic constraints and form/compositional constraints, the big thing it leaves is chronological time. I set aside time at least once a week where I play by myself, sit down and with a clear mind, see what comes out.

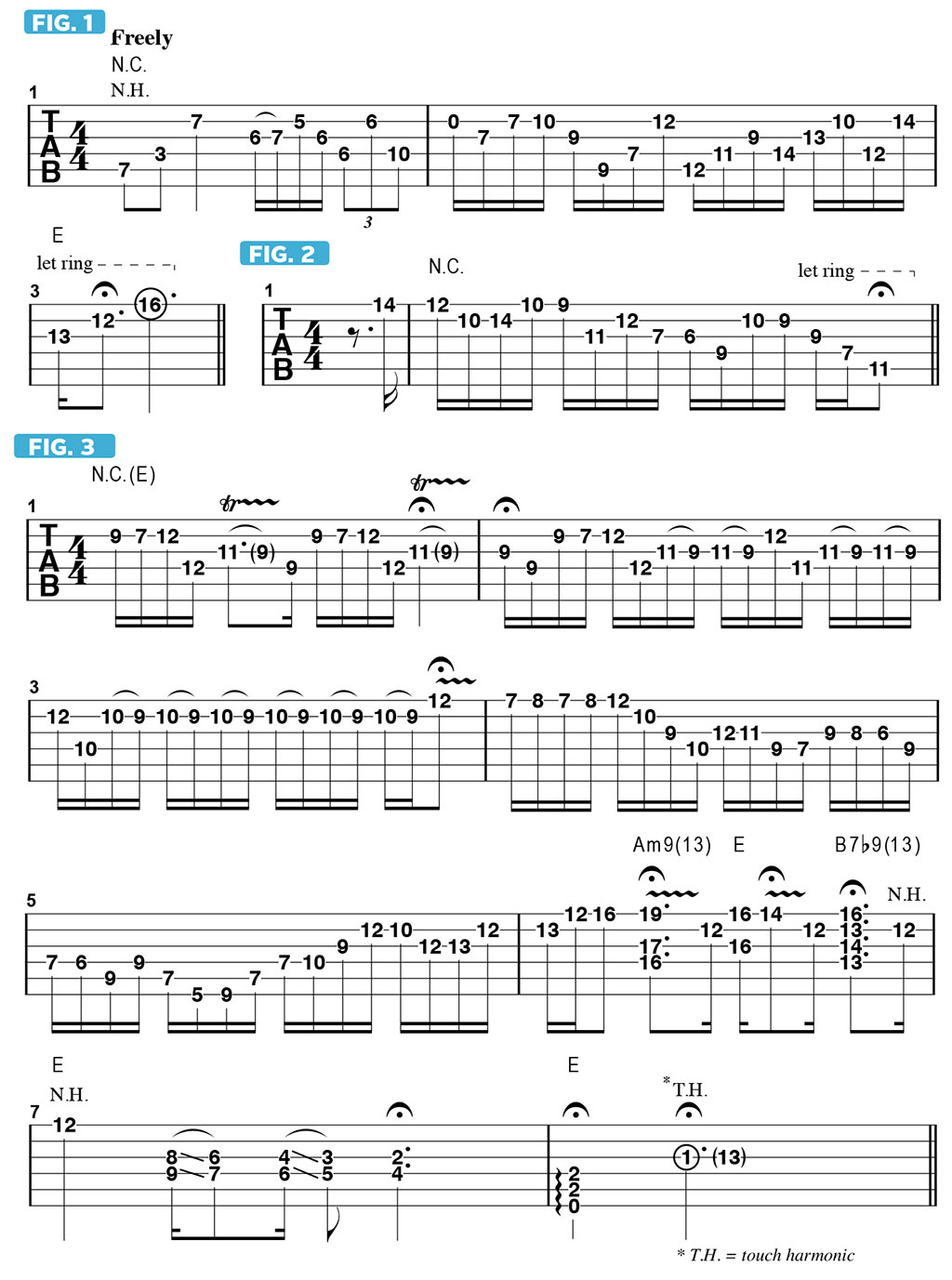

FIGURE 1 illustrates a “free” musical segment that my fingers discovered by moving around the fretboard. I then will think about what I played, evaluate it in some way and think about what I’d like to do next as a follow up. Improvisation is sometimes described as composition that happens in real time, so the next thing I’d play would be something that grows from that final E chord in FIGURE 1, as I do in FIGURE 2. What becomes clear to me is that I have arrived in the key of E, so that acknowledgement of a tonal center will help to direct the music that will come next.

From there, I will set a timer for about a minute, and I will finish playing that “song,” as I do in FIGURE 3. It started with no plan, a tonal center emerged, and then I followed that strain to new musical territory.

If you incorporate this approach into your regular playing routine, you will begin to develop your own style and vocabulary of “free” playing, with your own sense of pacing and harmony. I encourage you to record it so you can then listen back and see just what new musical avenues have opened up to you.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Julian Lage is a world-renowned American jazz guitarist and composer whose latest album is 2019's Love Hurts.