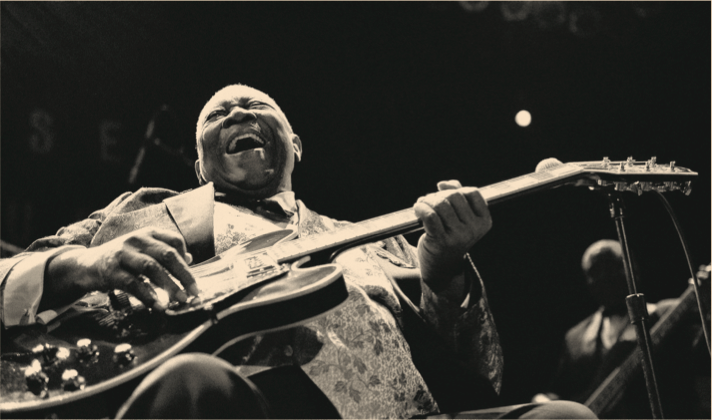

B.B. King: why the blues legend is the most influential modern guitarist

B.B. King was a giant of the electric guitar and the leading figure in blues

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Giants never grow old and die, at least in fables.

But B.B. King, a giant of the electric guitar and the leading figure in blues, who surely had a fabled life, died on May 14 at age 89 from a series of strokes stemming from the type 2 diabetes that he’d battled for decades.

“When I die,” King told me in 1998, “I’d like to be remembered as a good neighbor, a good friend…a guy that loved music and loved to play it. And who loved the people that love it.”

That modest desire has been well exceeded. King was simply the most influential electric guitarist—a stinging stylist with unmistakable vibrato and tone who had a profound impact on a plurality of players, from ultimate A-listers like Eric Clapton, Jimmy Page, Jeff Beck, George Harrison, Buddy Guy, Jimi Hendrix, Joe Perry, Joe Bonamassa and Brad Paisley to newcomers like the Alabama Shakes and Hozier and wiz-kids like Quinn Sullivan.

And King’s name is synonymous with blues for listeners all over the world. Like Robert Johnson, Miles Davis, Johnny Cash, Jimi Hendrix, Duke Ellington and other music figures whose work transcends genre, King will be remembered long and well for his achievements.

But there’s more to King than the repository of technique, vision and history within the more than roughly 75 authorized studio and live albums and compilations in his discography, which spans from 1949 to 2012. King was a beacon for the best qualities of the blues genre that he played and revered—its beauty, depth of feeling, storytelling, originality, character and musical excellence and evolution.

He was also a kind, generous and gracious man who cared about the people he entertained and the people he employed. And King was a living link to an era when performers were truly shining ambassadors of the arts—larger than life in a way that reflected a knowledge that with their status came certain responsibilities to themselves, their fans, their creativity and the qualities that made them special.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Dignity, respect, humanity and kindness were traits that King practically radiated in his bearing as well as in the notes that he teased from his beloved six-stringed First Lady, Lucille.

For all of his success—a lawsuit filed by three of King’s 11 surviving children for control of his estate shortly before his death estimated his assets at $5 million—King’s broken-hearted Mississippi childhood left scars he carried his entire life.

Riley King was born on September 16, 1925, in the still-unincorporated community of Berclair, Mississippi, in the heart of the Delta’s Leflore County, about 17 miles from where the B.B. King Museum and Delta Interpretive Center, a monument to his achievements, stands today.

When King was four, his parents separated and his mother, Nora Ella, took him to live with her family about 50 miles to the west, in Kilmichael. For the few years he went to school, King walked six miles round-trip to a segregated one-room building. When he wasn’t in class, he earned 35 cents a day picking cotton.

Music became a balm by the time he was seven, thanks to the singing and guitar playing of Archie Fair, the preacher at the local Church of God in Christ. Fair let King play his guitar and urged him to preach when he grew up, but the blues of Blind Lemon Jefferson and Lonnie Johnson, who King heard on the radio, whispered of other plans.

Those plans must have seemed terribly distant to King after Nora Ella died. She was only 25, and he was nine.

“I remember when she was dyin’,” King said the first time I interviewed him, in the New York City offices of his record label. “She was saying to me—’cause I was her only child, very slim, very scrawny—‘If you’ll always be nice to people, there will always be someone that will stand up for you.’ And I swear she wasn’t lyin’. I’ve held onto her words my entire life.

“As I grew up in a segregated society, I found that working within the system got more done for me than working outside of it. I didn’t like segregation. I hated it! Later I did a lot of concerts to raise money for the Civil Rights movement. But I find that talkin’ calmly to a person, givin’ them the facts as you see them…they will usually listen. And I’ve had many people look out for me in many ways.”

The first were his mother’s family and Floyd Cartledge, the owner of the plantation where they sharecropped. “He let me stay in a cabin on his land by myself in exchange for performing house chores and milking the cows,” King said.

But the pitch darkness of the unelectrified Delta held terrors for a small boy living alone. “I would have supper with my mother’s people, and they’d pass the time by telling ghost stories,” King recalled. “Then I’d go to my cabin all by myself and stay up all night, scared to death.” He was also kept awake by hunger. Poverty made for meager meals.

There were also the too-real horrors of racism. King saw a black man lynched when he was a child, and as a young man working the cotton fields during World War II—King got a deferment because cotton was considered an industry crucial to the war effort—he was outraged by the breaks afforded German prisoners working under the searing afternoon sun. There were no breaks for the African-Americans who did the same labor, from sunrise to seven or eight P.M., six days a week.

“I’ll never forget it,” King said more than a half-century later. “It still gets me steamed up.”

The blues legend also felt the ache of the loss of Nora Ella throughout his adult life. “I still miss her,” he offered. “She was a very loving person. Very kind, and being with her made me feel happy and safe. I think that’s the reason why I’m crazy about women.” There’s proof of that “craziness” in the 15 children he fathered with various mothers.

The hardships of his childhood drove him. “I promised myself three things when I was a boy,” he said. “I would never sleep in a dark room—and to this day I don’t. Since all I had to wear was overalls, I swore to God that if I lived to be a man I would have other types of clothes. And finally, I would have what I wanted to eat, when I wanted to eat it. So those three things I do today, religiously.”

Nonetheless, King spent several years in the Nineties as a vegetarian. “I came home off the road and turned on the TV,” he recalled, “and they were showing a special about the raising and killing of animals for meat and fur. It made me sick. And I swore off eating meat.” But a few years later he was seduced back into carnivorism at a family holiday gathering. “There was turkey and ham and black-eyed peas and sweet potatoes, and it all looked and smelled so good,” King said with a chuckle.

Floyd Cartledge—who King called “Mr. Flake”—did him another kindness that would ultimately lead to King’s salvation and elevation. He advanced King $15 to buy a cherry-red Stella acoustic guitar when King was 12 years old.

A year later, with his guitar over his shoulder and his few belongings at his side, King left for Indianola, Mississippi, 68 miles to the east, and got a job picking cotton and driving a tractor on a bigger plantation. He joined a gospel group, but still fed his soul with Tampa Red and the other bluesmen he heard on the radio. And he found his future on the street corners of Indianola, where he began playing blues and gospel tunes on Saturday nights.

“I was makin’ $22.50 a week drivin’ a tractor, and that was big money, not only for a 14-year-old, but for a grown man,” King said.

“And on Saturday nights I would go sit on the corner of Church and Indianola streets, in the black part of town, but a lot of whites would pass through on their way downtown. When I played gospel songs, people would say, ‘Great job, son. Keep it up.’ But when I played blues they’d put money in the hat, and I’d make $15 on a Saturday night. That’s when I learned there was money in blues.”

After the end of World War II, King left Indianola for Memphis, riding 120 miles in the back of a grocery truck.

He had $2.50 in his pocket, since, like most sharecroppers, King’s earnings mostly went to pay off his “draw” at the plantation store where he purchased his and his wife Martha Lee’s necessities on credit. He went to Memphis looking for his cousin Booker, better known as the bluesman Bukka White.

White was a stocky rough-and-tumble man who’d done time in the Mississippi state penitentiary for a shooting and had written “Parchman Farm Blues” about his unwanted stay. He also composed and recorded the classics “Shake ’Em On Down,” “Po’ Boy” and “Fixin’ to Die Blues.” Dylan recorded the latter, and the other titles became staples of the Memphis and North Mississippi blues repertoire.

King was fascinated by the sound of White’s slide playing on National resonator guitars, and while King never caught the gist of slide technique, White’s lightning attack would have a profound influence on his own keening, treble-rich tone and the slide-like glissandos and trills that became elemental to King’s style.

King got a job welding by day and learned the lay of Memphis’ Beale Street nightclubs and outlying juke joints and roadhouses by trailing cousin Booker on his gigs. After eight months King returned to Indianola to pay off his draw by putting in more time at the plantation. He returned with his wife to Memphis in 1948, eager to start a band and kick off a career in music—which beat the hell out of cotton picking, welding or just about any other form of manual labor.

By now, jump blues bandleader Louis Jordan had placed 37 top 10 hits on the so-called “Race music” charts, featuring his horn-driven, infectiously uptempo and swinging sound. It caught King’s ears and would not let them go. So did the fluid, jazzy electric guitar of T-Bone Walker, whose “Call It Stormy Monday (But Tuesday Is Just As Bad)” had been issued in 1947 and sold strong for two straight years.

Walker’s tone, phrasing and delicate, dynamic bends—a logical extension of Lonnie Johnson’s swinging single-note style—became a blueprint for King’s playing, and Jordan’s Tympany Five group was a template for his first bands. Their call-and-response style of singing, where, in the case of Walker, guitar answered and buoyed each of his vocal phrases, also burned into King’s musical DNA and would remain a lifelong hallmark of his approach.

Striving to make a name for himself, King sought out the great and notoriously cranky harmonica player, songwriter and singer Sonny Boy Williamson, going to radio station WKEM in West Memphis, Arkansas, just across the Mississippi River from Memphis, to ask to sing on Williamson’s daily radio show. Impressed with King’s rendition of an Ivory Joe Hunter song, Williamson let King close that day’s broadcast and, since he’d double-booked himself for Saturday night, also gave King a gig at Miss Annie’s 16th Street Grill in West Memphis.

Miss Annie offered King—whose angelic, gospel honed voice still led his guitar playing—a standing gig if he could find a radio station to perform on regularly and plug his shows, like Williamson did.

King almost immediately got a spot on a new station, Memphis’ WDIA, with a signal that reached all the way south to New Orleans, sponsored by a snake-oil elixir called “Pepticon.”

A DJ told King he needed a snappier name than Riley, so for a time he billed himself as the Beale Street Blues Boy, which was shortened to Blues Boy King and, ultimately, B.B.

Shortly before King made his first recordings for Bullet Records in 1949, the ode to his wife “Miss Martha King” and the flip side “She’s Dynamite,” the legend of Lucille was born.

King was playing a roadhouse in Twist, Arkansas, when two men fighting tipped over a barrel of burning kerosene. As patrons fled, King fought his way back in to retrieve his guitar, a Gibson L-30 acoustic with a pickup, and barely escaped with his life. He named the guitar after the woman who’d inspired the fight.

Although King and his band performed constantly, he survived on scraps until 1952 when “Three O’Clock Blues” propelled him to fame. King’s version of the Lowell Fulson tune was cut in the Memphis YMCA and released on the RPM label. It was one of the year’s best selling R&B records and showed that King’s hard work and desire to evolve as a musician had paid off.

While his debt to Walker is plain in his guitar’s staccato phrasing and the song’s arrangement featuring horns and Ike Turner, the A&R man who’d brought King to the attention of label owners the Bihari Brothers, on piano, the fat sound of King’s guitar—likely a Fender Esquire—and the heavy, deliberate attack he employs are all his own. And so is the vocal performance, which soars to falsetto highs and swoops to warm, mournful lows that underscore the story of betrayal and sadness in Fulson’s lyrics.

King continued to work on his technique religiously throughout most of his life. In the Nineties, he even embraced writing and demoing songs on a laptop while his bus rolled. And he spent hundreds of hours mastering the phrasing and licks of Django Reinhardt, and finding ways to apply what he learned to his own distinctive instrumental voice.

Although King’s Fifties recordings, including his classic performances of “Rock Me Baby,” “Everyday I Have the Blues,” “You Upset Me Baby” and “Sweet Sixteen,” kept him on the R&B charts, his lot was not easy.

His touring was limited to the de facto ghetto of the chitlin circuit, the web of clubs lacing through the country’s rural towns and urban centers that catered to African-American audiences and artists. Pay was low, the hours long and Jim Crow was still institutionalized throughout much of America.

It was hard to find respite in decent hotels and even get served at restaurants without using the back door and eating on the bus. And the bus ate up revenue in repairs and, at one point, caught fire and burned at the side of the road while King and his band looked on. Divorces and troubles with the IRS threw King even more curveballs.

But at the end of the Sixties, things changed. White-boy rock stars like Eric Clapton, who told Rolling Stone in 1968, “I don’t think there’s a better blues guitarist than B.B. King,” and Keith Richards and Mick Jagger had been publicly praising their blues heroes for half a decade. And doors began opening.

King played two pivotal shows that year that ushered him through. In June 1968, rock impresario Bill Graham hired King to play at his Fillmore West auditorium in San Francisco. “I’d never played to people like this before—white, long haired kids,” King recalled. “My knees were trembling.” But when Graham introduced King as “the chairman of the board,” he received a standing ovation before he even hit a note. King began to cry.

A month later on the opposite coast, at Boston’s Fenway Park, blues champion Dick Waterman, who managed Son House, John Hurt, Skip James and Buddy Guy and Junior Wells, booked King to play at a rally for presidential candidate Eugene McCarthy. The senator’s motorcade ran late, and King stayed onstage playing hard, commanding the full house of 37,000 hippies and counterculture Democrats to attention—much as he did the African-American audience captured exploding in Chicago on his classic, influential 1965 album Live at the Regal—until the candidate arrived.

The next year King delivered a knock-out punch follow-up when the single “The Thrill Is Gone,” from the album Completely Well, used producer Bill Szymczyk’s elegant string arrangement to smooth some of the burrs off the bones of its powerhouse lament to reach Number Three on the Billboard Soul Chart and number 15 on the national Hot 100 Singles chart. Thus white mainstream America, and subsequently the world, discovered B.B. King.

King did not reach the upper echelon of the charts, save for the blues charts, where he’s consistently stayed a best-seller, again until 1988, when his collaboration with U2, “When Love Comes To Town,” hit number two on Billboard’s U.S. Rock chart.

Only King’s glorious bullhorn throat, honed in his early years singing unamplified in churches and juke joints, and the resonant voice of Lucille could make U2’s Bono and the combined sound of the Edge, Larry Mullen and Adam Clayton seem small.

He topped the charts again in 2000 with an assist from his friend and acolyte Clapton. Their duets album Riding with the King, titled from a John Hiatt song about Elvis Presley, netted one of King’s 15 Grammy Awards, which include a Lifetime Achievement Grammy, and sold more than two million copies. It also grabbed the Number Three slot on Billboard’s Top 200 Albums chart.

King thrived on being around people, which may have been a result of the early loss of his mother’s love and his lonely life as a child in the Delta. When his fortunes rose, he moved to New York City in 1968, and in 1975 was lured by the warmer climate of Las Vegas.

His jones for gambling could also have been part of Vegas’ allure. The only time King ever lost his temper with me was when I asked him about his fondness of games of chance and the rumors that circulated about him owing money all around town.

But when King simmered down, he admitted that he “used to do that, but when I go out now, it’s just for fun. One of the things I like about living in Las Vegas is that you’ve got music going from early evening until late morning. I don’t drink, but if I wanted to I could have a beer any time of day around people. I just want to be where things are going on.”

That same need may well have driven him to the road in his younger days, and kept him traveling past his performing prime.

Through the mid-Nineties, King played roughly 300 dates a year. That tapered off as he aged, and in recent years he played less than 100 shows annually. For the last decade, his decline was painfully noticeable to those who’d seen him at his long-lasting peak. Seated at center stage, he often spoke as much as he played, telling the same stories at every show, and his repertoire was static.

The last time I saw King, when he played at the club that bears his name in downtown Nashville several years ago, he’d also lost his patented vibrato—perhaps the most thrilling component of his playing. King’s concerts began being dogged by negative reviews in the press starting in 2012, with the Chicago Sun Times, the Los Angles Times and the St. Louis Post Dispatch all expressing dismay at the lack of focus, and songs, in his performances.

Last October, after touring for 65 years, King canceled his concert dates when he fell ill after a show at the Chicago House of Blues.

He was diagnosed with dehydration and exhaustion. In early April he was once again hospitalized for diabetes-related dehydration. And after yet another emergency hospitalization, this message appeared on his web site on May 1: “I am in home hospice care at my residence in Las Vegas. Thanks to all for your well wishes and prayers.” Thirteen days later he died in his sleep at 9:40 P.M. Pacific Time.

Many music world luminaries, and even the U.S. Senate, offered condolences and tributes in the days after King’s death. The most poignant, perhaps, came from his friend Eric Clapton, who posted a filmed eulogy on YouTube that looks as if he made it on his own smartphone.

“There’s not a lot left to say, because this music is almost a thing of the past now, and there are not many left to play it in the pure way that B.B. did,” Clapton offered, looking sad and haggard.

“He was a beacon for all of us who love this kind of music, and I thank him from the bottom of my heart.”