Tapper's Delight: 20 Challenging Tapping Licks

Guthrie Govan gives a comprehensive tapping lesson.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Fretboard tapping has earned a bad name in certain sectors of the guitar community. Some players dismiss it as a technique suitable only for perpetrating the worst possible kind of overblown, unmusical histrionics, preferably played through a wall of amps that “go to 11.”

If you feel that way, then you probably haven’t even managed to read this far. But for those of you who are still undecided about tapping, I would urge you to view the technique simply as an easy way to play notes you could never reach otherwise.

If you think of your tapping fingers as extensions of your fretting hand, you’ll find it easier to imagine how this technique can benefit virtually any style of playing.

Article continues belowTrack Record

In the world of rock, Van Halen’s self-titled 1978 debut album heralded a tapping craze that soon caught on like wildfire. In the years following the album’s release, gifted guitarists such as Randy Rhoads, Joe Satriani and Steve Vai used the technique in their own landmark recordings. If you want to hear tapping taken to new heights of invention, check out Freak Kitchen by Mattias Eklundh and Normal by Ron Thal (a.k.a. Bumblefoot).

Tone

For tapping, many players opt to use their guitar’s bright-sounding bridge pickup and a heavily distorted, or at least overdriven, tone, which serves to compresses the dynamic (volume) range of the electric guitar’s signal, amplifying the quieter notes and increasing sustain, although players like Stanley Jordan manage to tap with a very clean, neck-pickup sound. When tapping with a clean tone, you’ll find that a compressor can even out dynamics and add sustain.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Technique

Most tapping is performed on one string at a time using either the middle or index finger of the picking hand, depending on if, and how, you’re holding a pick. Some players will momentarily tuck the pick into their palm or cradle it in the crook of one of their knuckles when they go to tap and maneuver it back into its normal position (typically between the thumb and index finger) when they go to pick again.

This magician-like sleight-of-hand can take a bit of practice to attain, and for this reason many players prefer to just keep the pick in its normal place and tap with the closest available finger, typically the middle. Experiment and use whichever technique works best for you. Eddie Van Halen holds his pick between his thumb and middle finger and taps with his index finger, and Rhoads tapped with the edge of his pick, which produces a very distinct articulation. (Listen closely to Rhoads’ classic solos in Ozzy Osbourne’s “Crazy Train” and “Flying High Again” to hear the subtle difference in his tapping attack.)

Your speed and proficiency will increase if you minimize your movements and keep all relevant fingertips close to the strings when not in use so that they never have far to go at any given time. Depending on whether or not you’re holding a pick when tapping, you may find that resting, or “anchoring,” the thumb or heel of your tapping hand to the top side of the fretboard helps stabilize and steady the hand and increase the accuracy of your tapping movements.

The easiest way to train the fingers of your tapping hand is to learn from the way you perform hammer-ons and pull-offs with the more experienced fingers of your fretting hand. The following principles hold true for both hands:

- If you’re hammering a note, the force of your hammering motion will dictate its volume. The harder you hammer/tap, the louder the note.

- If you’re pulling off to a note, its volume is a function of how far you flick the string sideways (either toward the floor or ceiling) with the finger responsible for fretting the preceding note. This sideways flicking, or pulling, motion actually serves to pluck the string again and is what keeps it vibrating. If you were to just lift the finger directly off the string, the following note would be weak and barely audible. (Note that when tapping with a pick, the “pulled-off” note tends to be louder than normal due to the pick’s hard surface striking the string.)

Muting

Distortion amplifies the sympathetic vibrations of unfretted strings. When tapping, you should make a concerted effort to dampen any idle strings with various parts of both hands, something that requires a bit of practice and experimentation to figure out and master. To that end, many players will place a piece of foam or fabric against the strings in front of the nut. In addition, a cheap elastic-core hair tie stretched over the headstock and positioned over the fretboard is convenient for damping the open strings.

If you’re new to tapping, allow your fingertips time to toughen up and develop the necessary calluses. Hopefully, the rest will become clear as we go. We have a lot of licks to look at in this lesson, ranging from classic hard rock and metal lines to sequencer-like patterns and bluesy runs to jazzy arpeggios, so let’s dive in.

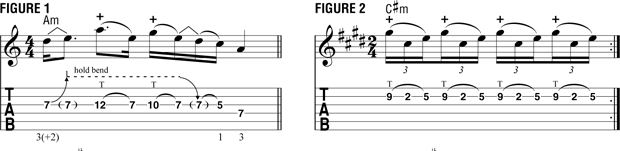

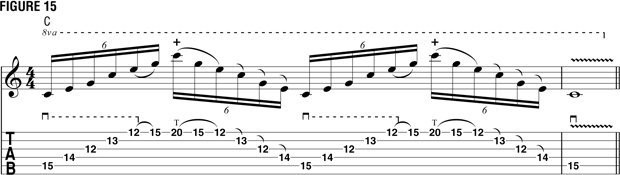

This is arguably the most versatile approach to tapping. A lick like this could sit comfortably in any rock, metal, blues, country or fusion context without necessarily invoking visions of Eighties-era spandex fashion statements. The recorded performance of this example on this month’s CD-ROM may sound reminiscent of Eddie Van Halen’s tone, but players of diversely different styles, ranging from Billy Gibbons, Brian May and Larry Carlton, have all dabbled in this approach.

There’s a strong argument here for using the middle finger of your pick hand to tap. By doing so, you can retain the pick in its conventional position and easily revert to picking at a moment’s notice. You can improve your accuracy if you anchor the heel of your tapping hand to the wound strings. This will also help mute unwanted string vibration while it allows you to keep a grip on the pick.

One tricky aspect of tapping a bent note like this is that the string moves closer to its neighbor (in this case, the D string), so you have to be extra careful to ensure that your tapping finger only makes contact with the G string. Try to bend the G string with your fret-hand ring finger while you simultaneously push the D string up slightly with the tip of that hand’s middle finger. This can help create more clearance between the two strings and provide a little more margin for error.

The following five examples serve as a great tapping primer, and there’s no other way to play arpeggio ideas like these with the same level of fluidity.

FIGURE 2 presents a classic Van Halen–style single-string triad tapping lick. This is the famous “Eruption” triad. To make this sound effective, the tapping finger must execute a strong pull-off as it leaves the ninth fret, thus ensuring that the Cs at the second fret rings out as prominently as its predecessor. You should also attempt to preserve a strict triplet rhythm, with every note equal in duration and volume.

Incidentally, there’s no single “right” way to execute a pull-off with the tapping finger. Some players prefer to flick the string upward, while others find it easier to flick it downward. Experiment with both approaches to find out which integrates more easily with the natural angle of your tapping hand and allows you to dampen the idle strings more effectively.

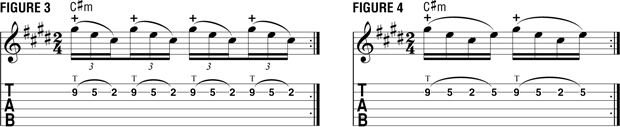

FIGURE 3 is a variation on the previous figure. Here, the order of two notes played by the fretting hand is reversed. It’s important that you become familiar with both approaches so that you can move on to ideas like the one shown in FIGURE 4, where the arpeggio goes all the way down and back up again, enabling you to move away from the ubiquitous triplet rhythm and phrase licks in even 16th notes.

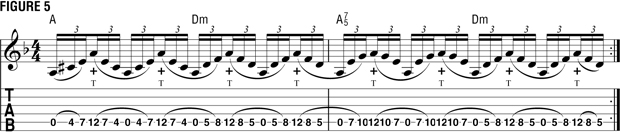

Here’s another twist, reminiscent of Van Halen’s tapping licks in “Spanish Fly” and “Hot for Teacher” and Satriani’s “Satch Boogie.” In this lick, the first finger of your fretting hand has to pull off to the open A string, preferably without disturbing the D string in the process. As ever, careful attention to damping and accurate timing of each note are the keys to making this lick flow clearly. To sound the very first note, pluck the open A string with your tapping finger. Once you’ve gotten the string moving, all the subsequent open A notes are pulled-off to with the fretting hand.

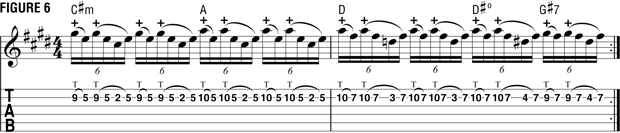

FIGURE 6 demonstrates how you can outline a chord progression with triad inversions. Notice how the lick lets you arpeggiate four different chords without moving either hand far from its starting point. This is done by analyzing the component notes of each chord and placing them so that they all fit into roughly the same area of the fretboard.

The tapping sequence is similar to that found in FIGURE 5, but since we’re tapping the highest note twice, the sequence is now six notes long. Players such as Rhoads and Nuno Bettencourt have used this variation to great effect.

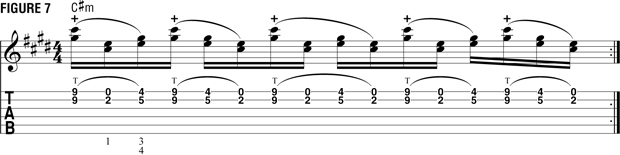

This next example isn’t reminiscent of any rock players and is intended to show how you can use tapping to create something a little bit different. If you start by looking purely at the B-string notes, you’ll see that the tapped notes outline a rhythm known in Latin music as the 3:2 clave: if you’re a fan of the bossa nova style, you’ll have heard this rhythm before. In this example, the fretting hand essentially does whatever is needed to fill in the gaps between the all-important tapped notes.

Once you’re familiar with the phrasing pattern, include the notes on the high E string, which adds a harmony to the B-string notes. Try tapping with either your index and middle fingers or the middle and ring (on the B and high E strings, respectively). The trickiest part here is arching your fret-hand fingers sufficiently so that the open E string is not muted by the underside of your index finger. Try to think like a classical player, keeping the thumb of your fretting hand based around the middle of the back of the neck.

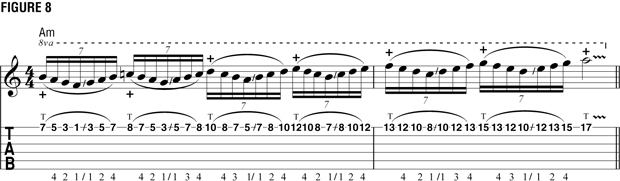

FIGURE 8 demonstrates how you can use tapping in conjunction with finger slides to cover a lot of the fretboard in a short amount of time and achieve a smooth legato effect. The note choice here is derived from the A Aeolian mode (A B C D E F G), but you can design similar licks using the notes of any seven-note scale.

At slow speed, it can be tricky to squeeze seven evenly spaced notes into each beat—most of the popular music we hear tends to divide the beat into twos, threes or multiples thereof, so a grouping of seven might sound a little unfamiliar—but you’ll find that this becomes less of a problem at faster tempos. Simply aim to nail each new beat with a tapped note, and you’ll find that the notes in between will tend to distribute themselves evenly as you speed things up.

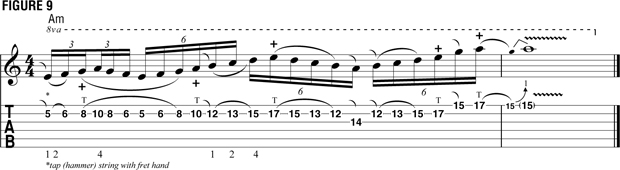

Here’s an interesting twist on the single-string scalar tapping approach. The first 10 notes look normal enough, but by the 11th you see that the fretting hand has leapt past the tapped note, to the 12th fret to perform a fret-hand tap, also known as a “hammer-on from nowhere.” The tapped note needs to be held at the 10th fret as the fretting hand quickly zooms up to the 12th fret, and you’ll need to be careful to ensure that the two hands don’t collide.

This lick won’t be for everyone, and it’s not particularly easy. On the other hand, it’s a useful approach whenever you’re trying to work out a fingering for something and it feels like you simply don’t have enough strings. This bypassing technique also has a certain flamboyant visual appeal, so it should come as no surprise to learn that Steve Vai was employing it as far back as the early Eighties.

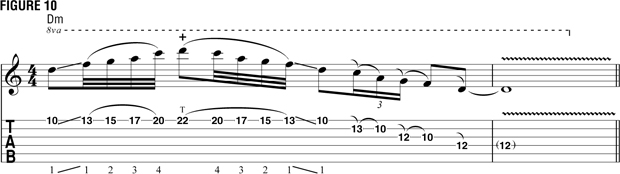

This example is inspired by Bumblefoot. The important part here is the first half of bar 1; the lazy approach would be to play two evenly spaced groups of five, but you get a wholly different effect if you prolong the two D notes (at the 10th and 22nd frets) and squeeze all the other notes into a shorter space of time. If you’re having trouble with the seven-fret stretch here, you could instead play 13-15-16-17 on the first string instead of 13-15-17-20. It doesn’t sound quite as cool to me, but it’s still a great lick.

Regarding the rhythmic phrasing of this lick, in FIGURE 8 we saw how an odd number of notes tends to be distributed evenly throughout a beat as you increase speed. Sometimes, however, it can be fun to resist that tendency and preserve a more distinct rhythmic contour, as we do here. The ear can still identify distinctions between the rhythmic values of the notes even when they are played at ridiculously high speeds.

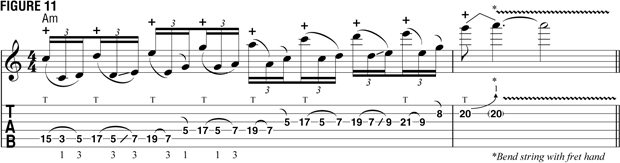

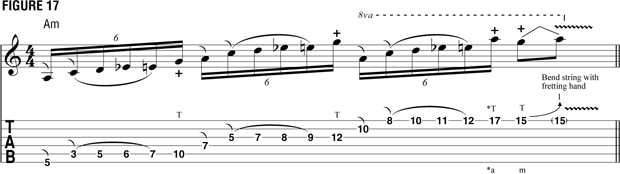

Here’s something a little more conventional. The idea is to play a blues lick with the fretting hand while highlighting certain notes by tapping them an octave higher. This is somewhat reminiscent of Nuno Bettencourt’s or Mattias Eklundh’s soloing styles.

The most challenging aspect of this lick is that you have to clearly and loudly hammer the first note on each new string with your fret-hand’s index or middle finger. This may feel a little weird at first, given that the index finger spends the bulk of its time acting more like a fleshy capo rather than as an independent hammering digit, so focus on executing the first-finger hammer-ons as cleanly as possible. This will be time well spent, as some of the subsequent licks will require much the same skill.

With regard to the final bent note: your tapping finger’s only role here is to hammer the note and then keep the string pushed down onto the fret while the fret-hand middle finger bends the string. As indicated, hammer the last note in the bar 1 with your middle finger, but once the tapped note has been initiated, there’s no harm in enlisting the fret hand’s ring finger to assist with the bend. As always, do whatever it takes to perform the job with the least amount of effort, pain and intonation issues.

Now for some more Van Halen–style fun. This lick is loosely modeled on a famous lick from “Hot for Teacher,” and it’s based on the A blues scale (A C D Ef E G). As with FIGURE 5, there’s a strong argument in favor of plucking the first note of the lick with your tapping finger. After that, each new string is greeted by a hammer-on, courtesy of the fret-hand’s ring finger. Hopefully you’ll find this easier than the first-finger hammering required in the previous example.

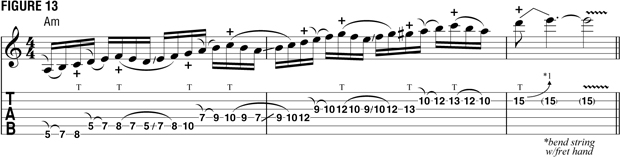

FIGURE 13 illustrates a scalar fingering approach favored by players like Greg Howe (who is featured in this month’s Betcha Can’t Play This, page 32). The fingering doesn’t incorporate any particularly wide intervals, and you could feasibly play the whole of the first two bars using strict left-hand legato, but by using the tapping hand to share some of the work you should be able to get more volume out of the lick while sparing your fretting hand from undue fatigue.

Here’s the downside: the tapped notes often fall in unusual places within the bar (rather than, say, on the downbeats), so this approach may feel a bit unnatural at first. Having said that, Howe’s exemplary playing is ample testimony to what can be done with this approach if you devote some time to it.

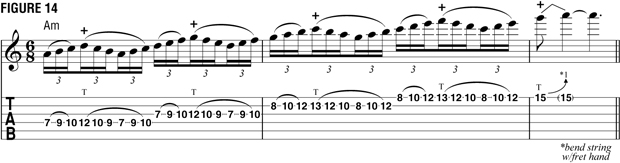

Here’s another scalar tapping concept. Most players would simply hammer the first note on each string with the first finger of the fretting hand, but the approach suggested in the tab here is based on the way Reb Beach (of Winger, Dokken, Night Ranger and now Whitesnake) would do it. Reb taps with his middle finger, so for ascending sequences he’ll use the ring finger of his tapping hand to pluck the first note on each new string. This may feel odd at first, but it undeniably gives you more volume and definition, particularly if you prefer not to use a lot of distortion.

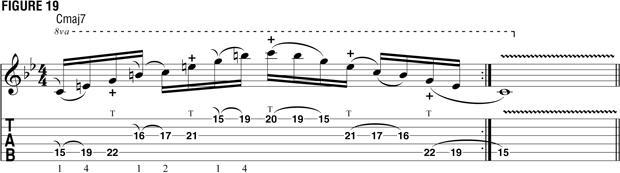

If you go to any guitar show or music fair and head toward the “pointy guitar” booths, you’ll hear a veritable army of players churning out the following lick furiously and repeatedly. It’s a simple example of a “sweep-and-tap” arpeggio, which can be viewed in three sections.

Section 1 (the first five notes) involves dragging the pick downward across the strings in a single stroke to outline the first five notes of this C major arpeggio. Ideally, each fret-hand fingertip should relax slightly at the end of its designated note to ensure that only one note is ringing at a time. By moving the whole picking hand downward as you sweep, you should be able to utilize your palm for a bit of extra string damping. High-gain settings are pretty much de rigueur for this kind of lick, so you can never be too careful when it comes to muting unplayed strings with both hands.

Section 2 (beginning with the sixth note) requires that you hammer the G at the 15th fret while bringing your tapping finger into position. The first three notes of beat two should then remind you very much of what we did back in FIGURE 3.

Section 3 involves the last three notes of beat two. You could either sweep these notes with a single upstroke of the pick, or do what most players prefer and use fret-hand hammer-ons while repositioning the picking hand for the next big downstroke sweep on beat three.

Note that most of this lick involves techniques other than tapping, yet that one tapped high C note makes all the difference, adding a pleasingly soft quality to the top half of the arpeggio and contrasting nicely with the more percussive sound of sweep picking.

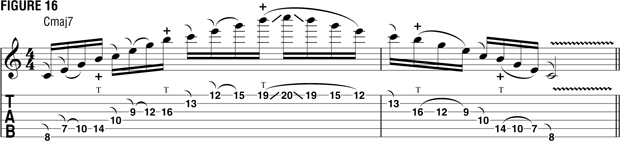

FIGURE 16 is an example of another approach to playing arpeggios, this one incorporating more taps, plenty of fret-hand hammer-ons and no sweeping whatsoever, resulting in a more fluid sound. Check out shredders like Scott Mishoe to hear this approach in action.

This example marks the first instance in which we’ve encountered a slid tapped note. You’ll find the key here is to slide with authority and to ensure the fingertip is constantly pushing on the string. Otherwise you run the risk of losing the note, particularly as you slide back downward. However, don’t press the tapping finger against the string any harder than is necessary, as doing so will create excessive friction that will slow you down and actually make the tap-and-slide more difficult than need be.

Here’s the same concept applied to a blues scale. Note that this and the preceding pattern are symmetrical, essentially featuring the same shape on each subsequent pair of strings.

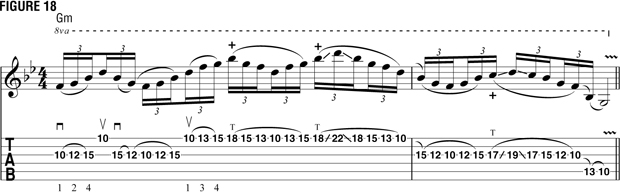

This run starts out as a signature Paul Gilbert string-skipping lick, then moves into tapping territory. Musically, all the notes (apart from that pesky C in bar 2) are from a Gm7 arpeggio (G Bf D F), but the overall effect is closer to that of a warp-speed G minor pentatonic (G Bf C D F) blues lick. The slides toward the end of bar 1 span four frets, so they’re a little trickier than the single-fret slide in FIGURE 16, but the principle is the same.

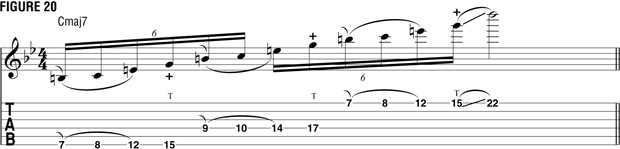

Here’s another arpeggio-playing approach that incorporates string skipping and tapping. Michael Romeo of Symphony X is rather partial to this approach.

If you’re not averse to a bit of fret-hand stretching, FIGURE 20 offers a versatile approach to playing major seven arpeggios. It has the same symmetrical qualities as FIGURES 16 and 17 and incorporates string skipping by cramming each octave’s worth of Cmaj7 arpeggio notes (C E G B) onto a single string.