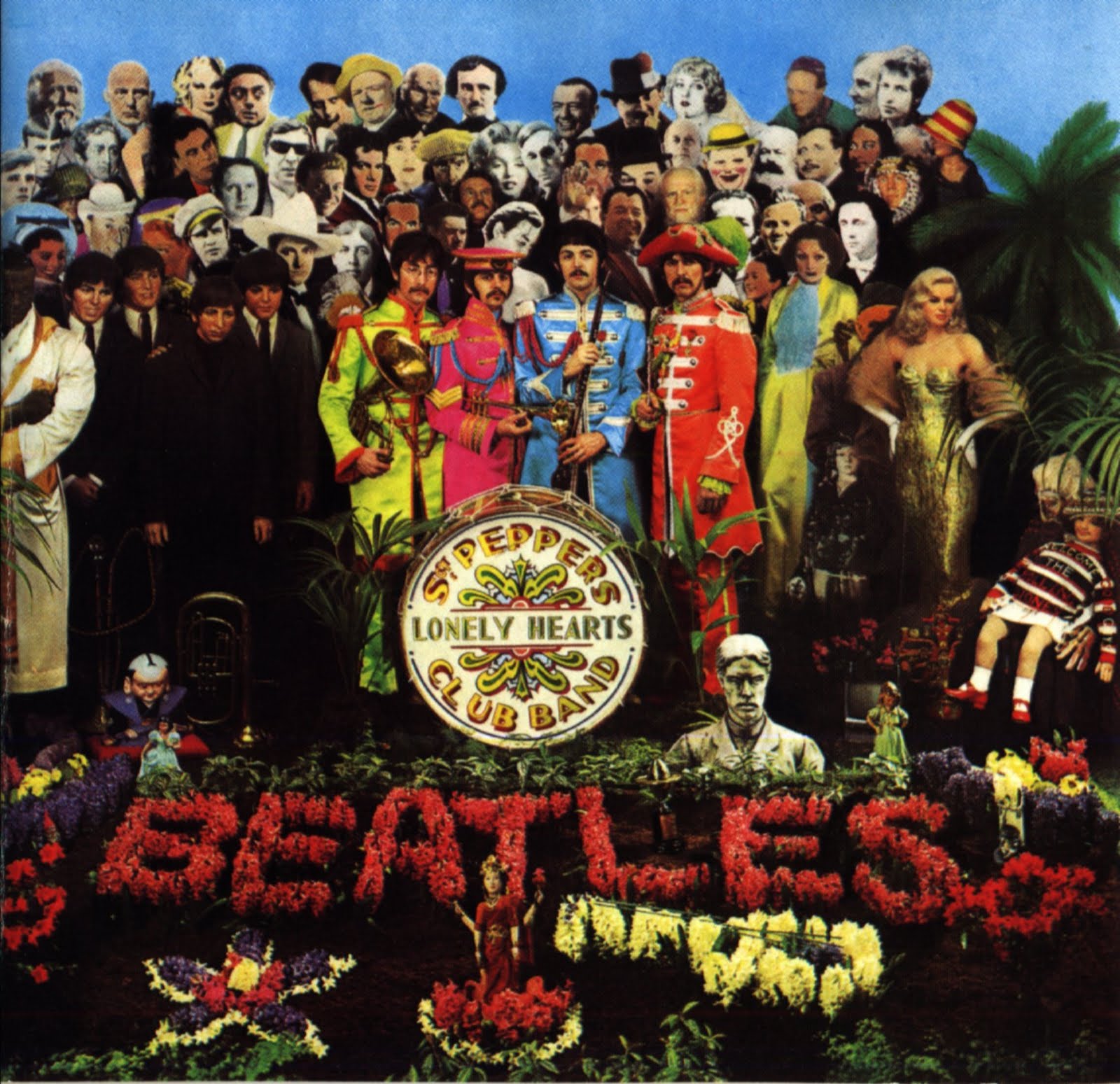

A Guide to The Beatles' 'Sgt. Pepper' Guitars and Gear

Guitar World's in-depth study of the gear and guitars used to record one of the greatest albums of all time.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The studio experimentation that had begun with Revolver advanced to the next level on Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.

In many ways, 1966 had been a watershed for the Beatles. They had broken from the two-albums-per-year formula that had brought their record company, EMI, so much money, but which had occasionally depleted the group’s well of creativity.

Revolver was the only full-length record they’d released that year, and it had been an artistically satisfying album, made at a more leisurely pace and with greater creative latitude. Revolver was also the first time they’d worked with engineer Geoff Emerick, whose gift for creating sounds had helped them see new possibilities—and opportunities—in the recording process.

Importantly, too, it was the last album for which they would tour, putting an end to the relentless performance schedule that had occupied much of their time between albums. As 1966 came to a conclusion, the Beatles were officially a studio group, and with Sgt. Pepper’s they would indulge their new-found freedom in ways that made other artists begin to think of the recording studio as a creative tool in and of itself.

Emerick would play an essential role in this, as he had on Revolver. But ironically, the 21-year-old audio engineer had not a single new idea when the sessions began. Martin and the Beatles had agreed that they wouldn’t repeat techniques used in the past: no vocals through Leslie rotary cabinets, no “Tomorrow Never Knows”–style tape loops and no backward vocals or guitars.

“But unfortunately, I had used everything at my disposal on Revolver,” Emerick says. “On Pepper, it was like starting over from scratch, getting down to the individual tonalities of the instruments and changing them. They didn’t want a guitar to sound like a guitar anymore. They didn’t want anything to sound like what it was.”

Emerick’s situation was complicated by the fact that nothing had changed at Abbey Road in the few months since Revolver had been completed: there were no new effects or innovations for him to exploit. For that matter, apart from the Mellotron keyboard used on “Strawberry Fields Forever” (the first song to be tackled at the sessions), the Beatles’ gear had hardly changed from what they previously used.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

On Sgt. Pepper’s, as on Revolver, Lennon and Harrison played their Epiphone Casinos, Sonic Blue Fender Strats and Gibson J-160E acoustic guitars; Harrison also played his Gibson SG. McCartney’s Rickenbacker 4001S was his main bass, and he used his Casino and Fender Esquire for rhythm and lead work.

As for amplification, the Beatles had at their disposal in 1967 a Fender Showman and a Bassman head with a 2x12 cabinet, a Selmer Thunderbird Twin 50 MkII, a Vox Conqueror and the Vox UL730, 7120 and 4120 bass amp used on Revolver.

And yet, despite the basic similarities in studio gear and equipment, Revolver and Sgt. Pepper’s sound distinctly different. Whereas Revolver sounds like a rock and roll album, with its crunchy guitars and warm, fizzy ambience, Sgt. Pepper’s is decidedly refined, lacking the low-midrange tones that gave Revolver much of its propulsive power. Emerick puts the difference down to the choice of studio.

“Revolver was done in Number Three studio, which is a smaller room. It was a dirtier-sounding studio acoustically.” Sgt. Pepper’s was recorded in Abbey Road’s fabled Studio Two, a large room well suited to handling the volume and frequencies produced by pop and rock bands. “Number Two is a brighter studio, and you can get cleaner tones,” he says.

In addition, Emerick began refining the recording techniques he had initiated on Revolver, finding new applications for them or applying subtle twists on familiar methods. “The only way to approach Sgt. Pepper’s was to use some of those techniques and sounds from Revolver in a more controlled way,” he says. “It wasn’t as brash—more fine tuned.” He also took advantage of an external equalization device built by Abbey Road’s engineering department: the RS127 “Presence Box.”

“We didn’t have much in the way of EQ controls on the console,” he says. “In the high-frequency range, you could adjust 5k, and that was it.” Built both in rack and stand-alone versions, the RS127 gave engineers control over three high frequencies—2.7kHz, 3.5kHz and 10kHz—with up to 10dB of boost or cut. It had been used on Beatles tracks long before Emerick began engineering the group’s sessions, but never in the way that he employed it.

“Often I’d put those in series, and I’d have like 30dBs of 2.7 on the vocals, to really screw them up,” he says. “ ’Cause the Beatles didn’t want voices to even sound like voices. It wasn’t a question of a little bit of treble; we just went overboard."

“That’s what it was about, especially for the guitars. I mean, with the tube equipment and those guitars, that 2.7k was just magic. Plus the Fairchild [660] limiter added so much presence to the guitar, it was unbelievable. It made it sound like a different guitar than it was.” Much of Emerick’s time was spent working on guitar tones.

“Because we were still mixing to mono in those days, I had to work out the details with the two guitars. It’s easy to get definition in stereo, when you’re putting one guitar left and one right,” he says. “But when they’re coming from one sound source, to actually make each one have its own spot and be able to hear every note of each guitar takes a long time.” For that matter, the EQ controls on the Beatles’ Vox amps of the period were as limited as the controls on Abbey Road’s mixing consoles.

“So it would sometimes take an hour and a half to two hours to get that sound worked out. I would spend a lot of time moving the mics”—specifically Neumann U47 large-condense tube microphones—“a short distance from the amps just to hear the slight difference in sound and get it absolutely right.” Emerick’s magic was especially evident on McCartney’s bass tracks.

In the months prior to making Sgt. Pepper’s, McCartney had fallen under the spell of the Beach Boys’ 1966 release, Pet Sounds. He was particularly enamored of Brian Wilson’s melodic bass work, which is especially prominent on the album. “The thing that really made me sit up and take notice was the bass lines,” McCartney says. “That, I think, was probably the big influence that set me thinking when we recorded Pepper.”

On previous albums, McCartney always laid down his bass parts with the rest of the group, but on Sgt. Pepper’s, Emerick gave him his own track, onto which he would record his bass parts, usually at the end of the long session day, when the others had left. “We’d pull his amp out into the middle of the studio,” Emerick says. “We’d put the mic about six feet away. We used to use the [AKG] C12 on the figure-of-eight [omnidirectional] setting to grab a bit of studio ambience.”

Devoting one of four available tape tracks to bass would have been an impossible luxury had Emerick and Martin not decided to “bounce” tracks from one four-track machine to another. When the tracks of one tape were filled, they would be mixed and recorded—“premixed” is the word typically used—onto one or two tracks of another four-track tape running on a second machine. New recordings would be added to this second tape, and if the recording required it, the process would be repeated yet again.

Since no one knew at any stage what additional instruments would be added to a song, Emerick had to use his best judgment when creating the premixes. “I did it as if I was mixing the final record,” he says.

“Once we’d done the premix and transferred it to a new tape, that was it; there was no going back and no way to change the mix on that track. So everything we added from that point on had to complement it. The benefit to that is that we immediately knew whether an overdub fit or not, because if it didn’t work with the premix, then it wasn’t going on.”

Though numerous important psychedelic albums were released prior to it—including the Yardbirds’ Roger the Engineer, Jefferson Airplane’s Surrealistic Pillow and the Who’s A Quick One—Sgt. Pepper’s defined the genre and became the soundtrack to the Summer of Love. “Everywhere you went that summer,” Emerick recalls, “you would hear it being played. It was a great time of experimentation. There were no time limits, and as far as cost—the Beatles’ attitude was, ‘Sod the cost! We’re making a masterpiece.’ Every day was groundbreaking.”

Christopher Scapelliti is editor-in-chief of Guitar Player magazine, the world’s longest-running guitar magazine, founded in 1967. In his extensive career, he has authored in-depth interviews with such guitarists as Pete Townshend, Slash, Billy Corgan, Jack White, Elvis Costello and Todd Rundgren, and audio professionals including Beatles engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Scott. He is the co-author of Guitar Aficionado: The Collections: The Most Famous, Rare, and Valuable Guitars in the World, a founding editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine, and a former editor with Guitar World, Guitar for the Practicing Musician and Maximum Guitar. Apart from guitars, he maintains a collection of more than 30 vintage analog synthesizers.