“Nobody ever came to a gig to watch me play guitar. They came to hear me sing. We didn’t have a rhythm guitar player, so I had to cover everything”: Justin Hayward on the life, times and tones of the Moody Blues, and the undisputed power of a dimed AC30

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In 1966, the Moody Blues were about to go down in flames. A year earlier, the London-based rhythm and blues group consisting of singer-guitarist Denny Laine, keyboardist Mike Pinder, bassist Clint Warwick, multi-instrumentalist Ray Thomas and drummer Graeme Edge had scored an international smash with their sumptuous version of Go Now (a 1964 hit by singer Bessie Banks), and they served as the support act on the Beatles’ last British tour.

Repeating that success proved difficult, however, and after follow-up singles stiffed, Laine and Warwick quit, and the Moodies seemed rudderless.

Singer and guitarist Justin Hayward was looking for a new gig. He’d left his hometown of Swindon for London in 1964 and found a job playing guitar for the popular British rock ’n’ roll singer Marty Wilde. But he kept his eye out for other opportunities and sent letters to various music management companies.

“I didn’t have much of a plan at the time,” he says. “I just didn’t want to have to go back and live with my parents.”

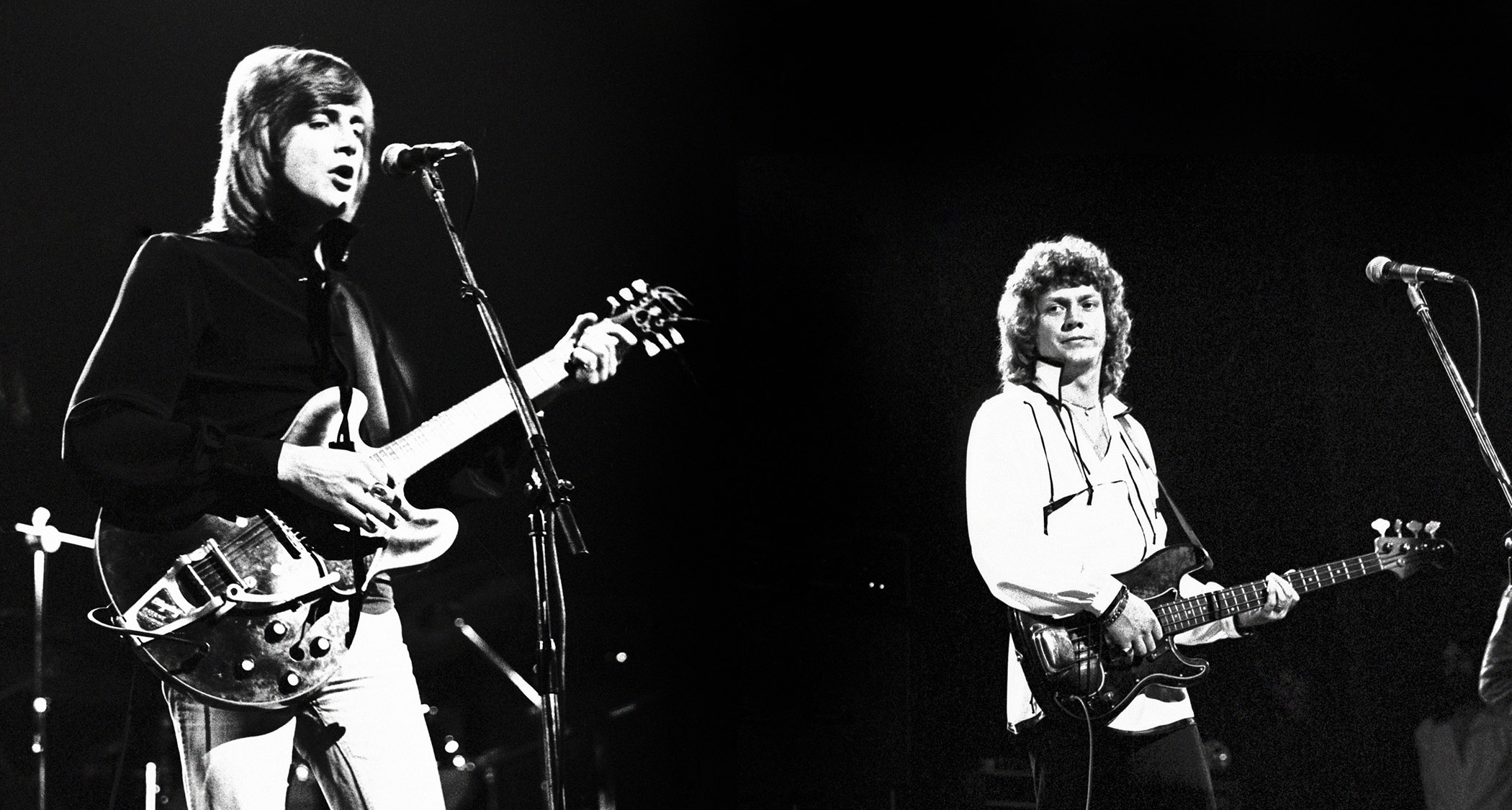

Mike Pinder got wind of Hayward’s availability and recruited him to replace Laine. At the same time, bassist and singer John Lodge was brought in as a replacement for Warwick. It was a tough slog at first for the new quintet as they attempted to include new material written by Hayward and Lodge into their repertoire.

“On tour, we had to do two 45-minute sets,” Hayward says. “The first set was rhythm and bluesy covers, and the second was our own songs. Finally, we started to get an audience that came out for our new stuff.”

After scoring an almost-hit with Hayward’s psychedelic-folk single Fly Me High, the band fully embraced their new direction, and with Pinder incorporating the Mellotron into the group’s rapidly evolving sound, they set out to record an ambitious concept album that would mix rock and orchestral elements.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Released in November 1967, Days of Future Passed built on the “anything goes” rock-as-high art template set by the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper – it was lush, romantic and trippy, mixing breezy rockers with sunny pop. Everything (including the London Festival Orchestra) came together spectacularly on Hayward’s grandiose anthem Nights in White Satin, a track that would enthrall and beguile generations of music fans.

“Our record company, Decca, was run by an elderly gentleman [Hugh Mendl], who put the studio in our hands,” Hayward says. “After Days of Future Passed, the feeling was, ‘These young boys clearly know what they’re doing. They can do whatever they want. Just let them make records.’ That’s how life was in general. I think there was a belief that young people knew what they were doing.” He chuckles. “It was nice while it lasted.”

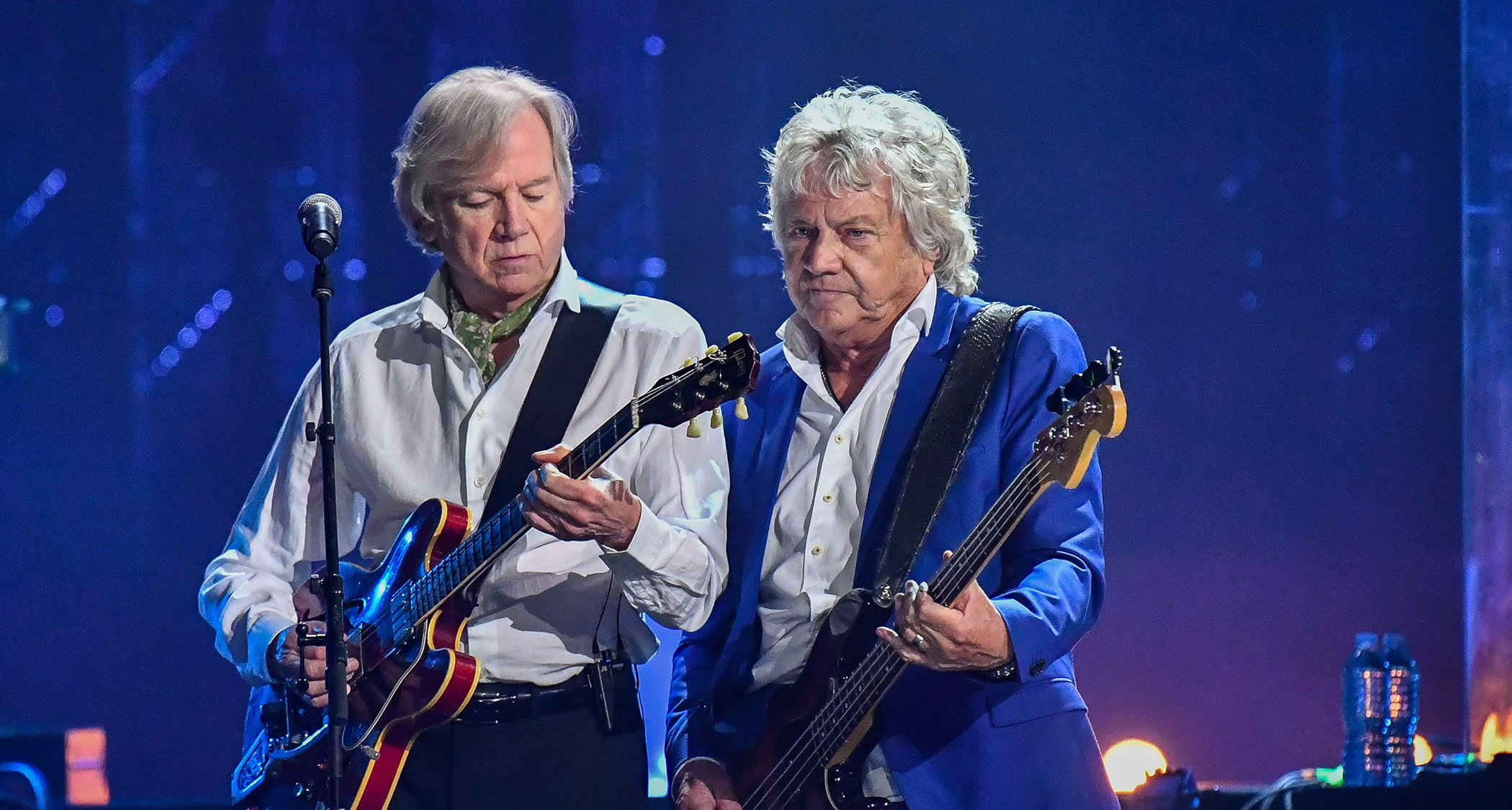

Over the course of the next five decades, Hayward and Lodge served as the group’s main songwriters, rarely collaborating, though they did team up during the Moodies’ five-year hiatus in the mid-’70s for the splendid album Blue Jays, which included Hayward’s atmospheric gem Blue Guitar.

As a player, Hayward eschewed showboating sections of virtuosic flash, but within the framework of his songs he provided plenty of six- and 12-string magic. His exuberant acoustic strumming on Question is rhythm guitar nirvana, and his rollicking riffage on You and Me should be inducted into the Rock and Roll Intro Hall of Fame.

On one of the Moody Blues’ biggest hits, The Story in Your Eyes, he’s a one-man guitar mean machine, churning out gnarly rhythms, spunky passing lines and a gloriously fuzzed-out solo fireball.

Asked if he ever feels underappreciated as a player, Hayward lets out a good-natured laugh and says, “Nobody ever came to a gig to watch me play guitar. They came to hear me sing. Now, as I was the only guitar player in the band, I strove for a good sound, and I always had nice guitars.

“I learned what worked and what didn’t work. We didn’t have a rhythm guitar player, so I had to cover everything. But like I said, nobody came to watch my left hand. I was fortunate to get a lot of girls who came to see what I looked like. We were a nice-looking band – that didn’t hurt.”

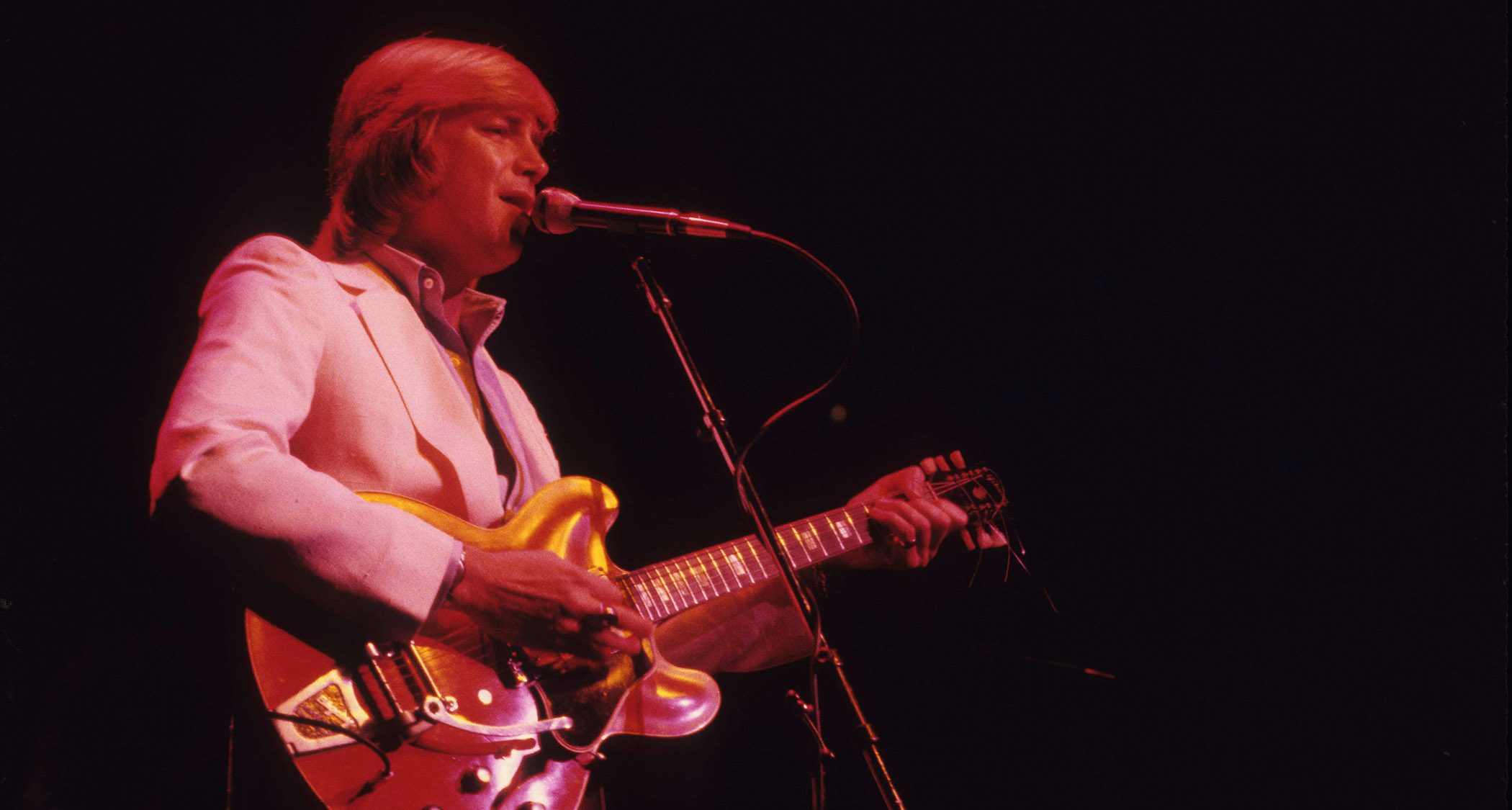

We associate you with the red Gibson ES-335 you’ve played for so long. How did you gravitate toward it?

“I saw Joe Brown in the 1950s. He came to Swindon, and I loved that ’59 sunburst 335 DOT he had. He and Marty Wilde were best mates, so when I was with Marty I got to be around that guitar. In 1963, my parents were kind enough to go guarantor for me to buy a brand-new 335, and I had it all the time I was with Marty.

I’d heard Go Now and thought it was fantastic. I was struck by Mike’s right hand playing the piano. When he called me to join, I thought, ‘Oh, he’s the guy who plays piano’

“Maybe a month or six weeks before Mike Pinder called me to join the Moodies, I didn’t have any money, so I sold the 335 and bought a Telecaster because I needed something that was good but cheap. It was a nice guitar, but I wanted a 335 again.

“I found the red one – it was a hire guitar from Selmers. It had the Bigsby on it, and I fell in love with it. I begged them to sell it to me, but they wouldn’t because it was their most popular hire guitar.

“Eventually I said, ‘Listen, I’ll give you whatever you’d want if it were new.’ They said, ‘Oh, all right. You’re clearly not going to give it back.’ So that was that.

“I bought a sunburst DOT reissue in 1995, and the level it puts out is really strong. My red 335 doesn’t have that level, but I can compensate with TC Electronic boosters. I used to put it through the normal channel of a Vox AC30 and just turn it full up. It was a dream sound.”

Before you joined the Moody Blues, were you a fan of their earlier work?

“I’m from a very different part of England. The other guys are from Birmingham, and I’m from Swindon, so we didn’t have much in common. But I’d heard Go Now and thought it was fantastic. I was struck by Mike’s right hand playing the piano. When he called me to join, I thought, ‘Oh, he’s the guy who plays piano on that record.’”

When you joined the band, did you feel as if your songwriting was already fully developed?

“Yes. They’d called themselves a rhythm and blues band, and they were doing covers. I was lousy at rhythm and blues, and I knew that wasn’t my thing. I thought of myself as a songwriter.

“Now, fortunately, Mike Pinder did as well. He was in kind of the wrong band, and I think Graeme and Ray were also in the wrong band somehow. When John and I joined, everybody was suddenly in the right band. The pieces fit.”

How influential was Mike Pinder’s use of the Mellotron to your songwriting?

“Oh, it made my songs work. It made my sound. It was what my songs had been waiting for. I mean, we did try to continue with the piano idea; Mike was comfortable in a pub playing piano, but not in a band.

“We found a Mellotron up in Birmingham at a social club. It was a sound effects instrument, but it also had orchestral sounds. Mike duplicated those orchestral sounds twice over – he double tracked them – and they sounded great. I don’t think it affected my songwriting, but it made the point of the songs better.

“But you know something? When I took Nights in White Satin into the rehearsal room – I’d written two verses of it the night before – I played it to the other guys, and they were pretty disinterested. But Mike said, ‘Play it again,’ and he played along to it on the Mellotron. Then everybody went, ‘Hey, that’s good. This could work.’ That’s the difference it made.”

I want to throw out some song titles to get your thoughts. Question. Your brisk acoustic strumming is phenomenal. Where did that come from?

“I’ll tell you where that came from. It came from me. [Laughs]”

But who were you listening to? Who inspired that kind of playing?

“I admired Richie Havens very much. We did a few gigs with him, and I saw him at a festival in ’69 and he played like that. I have to give him credit for that. Question is in an open tuning; it’s not Richie’s tuning, but it just seemed to fit this big old 12-string. In normal tuning, I could never get the intonation right, but it worked fine in open tuning. But yeah, Richie Havens was an inspiration.”

The Story in Your Eyes is a brilliant rocker – and what a great overdriven guitar sound! Is that the 335 through the AC30?

“Yes, through the normal channel of a Top Boost AC30, full up.”

Even the fuzzed-out solo?

“No, the solo was through a unit that Marshall made for a little while. It was a circuit board that looked like a 50-watt amp top. It had a spring reverb in it, but I took it out. If you turned the tone all the way down, it just seemed to sing.

“Plus, with the AC30, you had to stand at a certain angle. It was very responsive to where you were with the guitar. Once you found that spot, you had to stay there.”

Did you ever hear the versions of the song by Stiv Bators and Fountains of Wayne?

“‘I don’t know’ is the answer.”

In the opening seconds of It’s Up to You, there’s a little bit of what sounds like pedal steel guitar. But we never hear it anywhere else in the song – or in the Moody Blues’ catalog. Is that you playing pedal steel?

“Yes. Rotosound were kind of experimenting with some kind of pedal steely thing that had a different setup than what the country guys in Nashville used. They gave me one. I could never do the bottleneck things on it, but it did have foot pedals, so I could just go making this sound with an E chord.

“I’ve still got it. It’s in my attic, and I look at it every now and again. It’s too complicated to screw it all together; you’d have to build the bloody thing first. I never used it on any other tracks. I wasn’t that good with it. I’d leave that to guys who could do that stuff properly.”

You and Me features one of the greatest unsung guitar riffs of the classic-rock era. What inspired that?

“Oh, well, thank you. I had that riff for ages. [Sings the riff] Graeme really liked it. I had the kind of chorus, but I didn’t have words. It didn’t seem like my usual kind of love song, and I didn’t have a girlfriend I could dedicate it to at that particular moment.

“That’s probably not true, but songs are not really about actual events; they’re just about a lot of things coming together and your emotions in a particular moment when you’re sitting on the side of the bed.

“I said to Graeme, ‘Well, why don’t you write some lyrics?’ Because he always wanted to write a song, but phonetically he could never get it together.

“I would always say, ‘It’s not what you say, Graeme. I know you want to use words, but it’s the phonetic sound of the words that’s more important.’ And he came up with some great kind of poetic lyrics and just knocked them around phonetically. It’s one of the nicest things I’ve ever done because it was done with real love. Graeme really loved it. The riff was just a dream for me to play.”

Is the riff double-tracked?

“No, I don’t think it is. It was just the way [engineer] Derek Varnals at Decca recorded it. It was too fast to double-track.”

What was your main acoustic guitar during the period of, say, songs like Are You Sitting Comfortably or Fly Me High?

“I had a guitar Lonnie Donegan had given me. I went to his house one day, and he said, ‘What’s in my attic? Climb up there and have a look.’ So I went up – there were a few things, and he said, ‘That’s shit. I don’t want that. You can have it.’ He gave me a Francis 12-string that I renovated. I did the nut and the bridge and fixed the neck. That was the 12-string I used on Nights in White Satin, Fly Me High – everything.

“Because the guitar became famous, Lonnie sent someone around when I was out. He said, ‘Can Lonnie borrow that 12-string?’ My girlfriend said OK, and the guy said, ‘I’ll bring it back tomorrow.’ And it never came back. I did buy it back from Lonnie’s widow after he died.

“After I’d lost the Francis, Mike and I went up to Selmers on Charing Cross Road [in London], and we each bought a Yamaha FG-130. That’s what I used on Never Comes the Day and all of those things.”

“In the early days of touring in America, we were always on the bill with about four or five other groups. There were these boys who would turn up with a van full of great guitars; they took them around to concerts because they knew they could sell them to the bands. We’d come off the stage and these guitars would be lined up.

“One night, I walked off stage and saw this D-28 for sale. It was a ’55 or ’57; I still don’t know to this day. But I tried it, and it was the most beautiful guitar I’d ever played in my life – the intonation. I still have it. I’ve tried other Martins, of course, and was like, ‘Nah, it’s not as good.’”

Was the AC30 your main guitar amp for the classic albums between 1967 and ’72?

“Yes. After a while, our concerts got bigger and louder, so I had to get louder. The Marshall came along; I went to a 100-watt top and a 4x12 cabinet, and then I had two 4x12 cabinets.

“Then we went to Hiwatts. It just got louder and louder. We became two bands – a recording band, so I could use my AC30 Top Boost – and a touring band with the Marshalls and Hiwatts.”

On Blue Jays, did you do anything new or different to change your guitar sound?

“I don’t think so. I was just experimenting with sounds. I found a compressor – it was before Ross or Roland – and it allowed me to go straight into the desk. Also, I had collected a couple of other guitars. I had a red Gretsch; it might have been a [Guild] Starfire. Mike really loved it. And, of course, I had a Telecaster. It was a little selection of electric guitars. I couldn’t use the 335 on everything.”

You tend to downplay your guitar playing, but during the ’60s and ’70s, were there any guitarists – besides Richie Havens – that you tried to borrow from?

“I never really did that. There were guitarists I would faithfully go see, like Roy Buchanan. He was totally unique. But I never really went to see guitar players with an eye toward changing anything.

“I liked what I had, and if I ever tried to play like somebody else, it wouldn’t have come off. Of course, you hear riffs and think, ‘I could try to make that my own somehow,’ but in the end I played like myself.”

A band that has a long career is bound to have ups and downs, albums that work and ones that don’t. In your view, did the Moody Blues ever have trouble adjusting to changing times and tastes?

Some of the other guys didn’t like this way of doing things. They wanted to work things up in the studio, like a jam session. But that wasn’t Tony Visconti’s style

“At the end of the ’70s, we were trying to tighten things up – no more fillers on albums. Certain producers made a big difference. Pip Williams had a particular way of loving the band and wanting to hear us in a different way. Then I met Tony Visconti, who really opened my eyes. He brought a discipline to the recording in that you started at 11 in the morning and finished at 7. If you were in the middle of something, it didn’t matter; the lights were going to go off.

“I found that discipline refreshing, because I’m a guy who writes songs at home, and I know what everybody should play. I’m the group member from hell, because I’m going to tell you what to play, and I’m going to sit there looking bored when you give me your ideas.

“Some of the other guys didn’t like this way of doing things. They wanted to work things up in the studio, like a jam session. But that wasn’t Tony Visconti’s style, and I quite liked it. Tony made us relevant in the ’80s when we really needed it. Otherwise, we would have went down – although we still looked good. [Laughs]”

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.