All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

"It's a long way to the top if you wanna rock 'n' roll." Truer words have not been spoken.

And no one knows the value of those words better than Mark Evans. From the time he joined AC/DC at age 19 right up until today, Evans has seen the highs and lows the rock 'n' roll lifestyle has to offer.

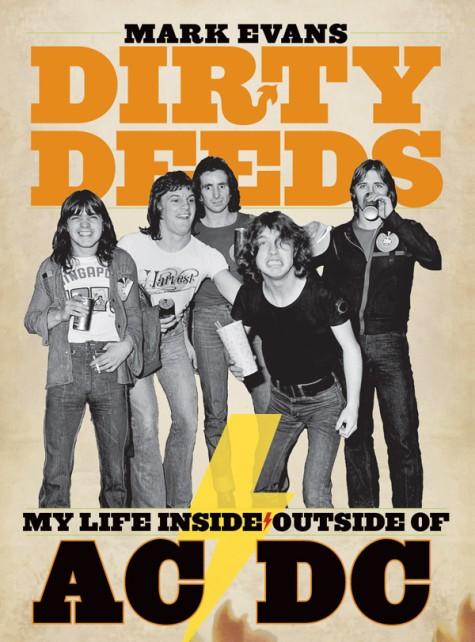

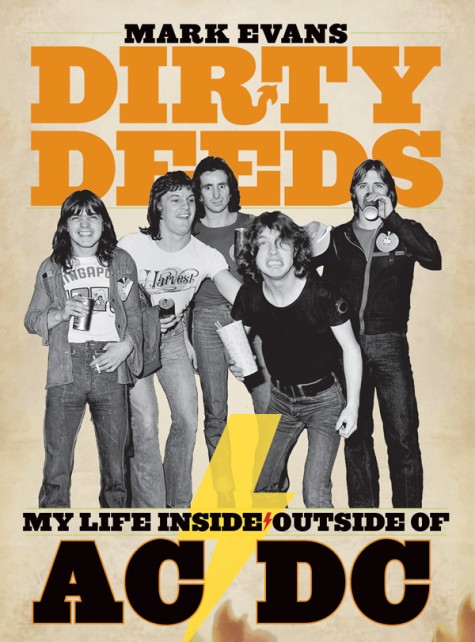

In his new book, Dirty Deeds: My Life Inside/Outside of AC/DC, Evans details his upbringing and how he came to join a little bar band in Australia that would eventually blossom into an international tour de force. Along the way, he paints a picture of the Young brothers and Bon Scott that few, if any, who weren't in a band with them would have been able to do.

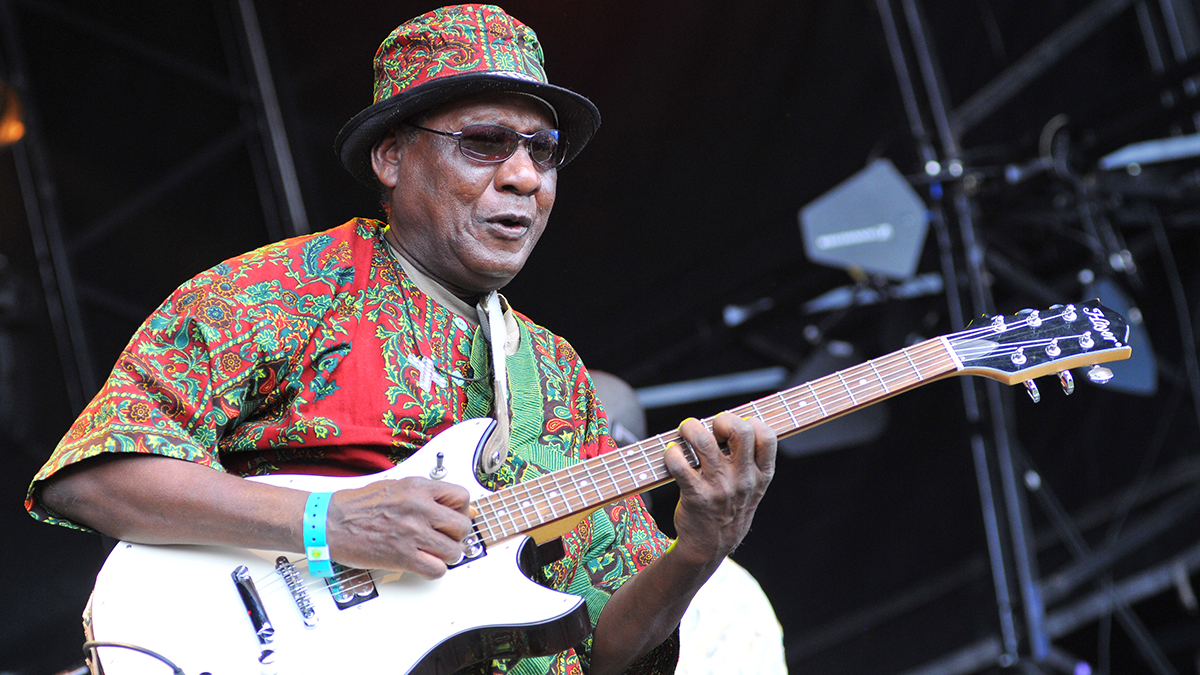

After spending three years touring and recording with one of rock's all-time great bands, Evans was unceremoniously dismissed in 1977 while the band was on a break in London. The split proved difficult but also rejuvenating for Evans, who would later go on to play with Finch, Swanee, Cheetah, Heaven and the Party Boys. Today, Evans enjoys a passion for collecting and dealing in vintage instruments and performs alongside singer Dave Tice in an acoustic blues duo.

I recently had the chance to catch up with Evans to talk about the timing of his new book, his time in AC/DC and why the Telecaster hasn't changed much since the 1950s.

What made you decide that now is the right time to get your story out there?

Well, the motivation behind it, basically, was all the punters and supporters coming to gigs and asking me, "What was it like being on the road with AC/DC?" and "What was Bon Scott like?"

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

It's my way of paying the punters for all the support over the years. I decided to put some stories down, and it just grew from a book that was just about my time with the guys into a complete memoir, a complete autobiography. It just came along at a time when I really wanted to immerse myself in something, so the timing was right. The way book turned out, I'm very, very happy with it.

It's definitely been one of my favorite reads this year.

So you've read the full thing?

Yes.

Oh, good! Then you know it came along at a time when I had a real need to immerse myself in something. It was a great opportunity to sit back and take stock of what's happened so far and look forward to what's going to happen next.

What were your first impressions of the Young brothers?

Riveted. From the get-go, standing in the hallway seeing AC/DC in Melbourne, I knew from playing the first 12 bars of the first song, a song called "Soul Stripper" from the Australian version of High Voltage -- it was just the biggest lightbulb going off in my head -- I just knew that's where I was supposed to be.

As far as a two-guitar-player setup goes -- and I'm biased, of course -- I don't think there's two guitar players that mesh as well as those two. They're something else. Great players, man. Malcolm's credibility is unquestionable because of his rhythm playing, but I don't think he gets enough recognition for his guitar playing. He's an amazing guitar player.

I've read a couple of interviews where Angus said the Malcolm was actually the better lead player and that he just wanted to play rhythm because being a lead guitarist interfered with his drinking.

[laughs] Yeah, that's a great one! Both of them, though, great guitar players.

With guitar being so up-front in AC/DC, how did you approach finding your place in the sound of the band as the bass player?

The strategy was very easy, just nail the grooves down. Play it straight, you know? When you're playing in a band like that, and you've got Phil Rudd on the drums and Malcolm playing rhythm, if you can't play bass for those guys, then you're on the wrong career path! You're flying first class with those guys.

My first conversation with the guys, Malcolm asked me what my thoughts were on bass playing, and I said that I just wanted to tie it down. I pointed to my favorite bass player at the time, a guy named Gerry McAvoy, who was Rory Gallagher's bass player. He just played it straight, you know? And that definitely struck a chord with Malcolm, so to speak.

I always thought you and Phil were one of the more underrated rhythm sections in rock simply because neither of you overplayed. Phil was a drummer who knew he didn't have to hit a crash on every downbeat.

It's interesting you say that, because I've seen AC/DC play a number of times on different tours when Phil wasn't in the band and I don't think people realize how important Phil is to the band. I'm probably the worst person to comment on this, because when I hear AC/DC in my head it's always Phil playing. All respect to Simon [Wright] and Chris [Slade], but it sounded like a different band to me. Phil's the heartbeat of that band, along with Malcolm, of course. In my mind he's an indispensable part of AC/DC, no question about it.

Malcolm had been playing bass in the band prior to you joining. Was there ever any added pressure when auditioning for him considering he was the guy you'd be replacing?

No, not at all. Malcolm's rhythm playing is so intrinsic to the sound of the band. He was just looking from playing bass, and the style of bass playing the band were after was not necessarily the way that Malcolm would play bass. Malcolm is probably like George Young, his brother; when they play bass, they're both great bass players, but they tend to be a bit more notey, a bit more busy than what the job called for.

When I saw the four-piece AC/DC with Malcolm on bass, they were phenomenal. Malcolm's bass playing was probably kind of similar to Andy Fraser's. Killer bass player. I don't think I've ever seen Malcolm attempt something that he couldn't master quite quickly.

What do you remember about the recording process in those days? In the book, you talk about some albums being done in as little as two weeks.

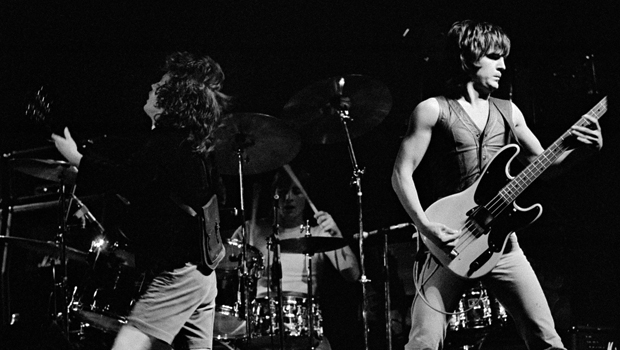

Yeah, pretty much! The three studio albums I did with the guys -- the Australian T.N.T., which eventually became part of High Voltage, Dirty Deeds and Let There Be Rock -- were all recorded in a two-week period.

The first week would be set aside for putting the backing tracks together -- which would include writing them, I might add. We never did demo recordings; we never had the time because we were constantly on the road in those days. The backing tracks were recorded all in a week and written in the studio. George would get together with Malcolm and Angus and they would knock the structures of the songs together. We would sit down and groove 'em out and get the backing tracks recorded that first week, and then after that it would go straight over to Bon, who would start fitting up words for it.

It's incredible, but those three albums were recorded in a two-week period. We'd record and then leave it with George and Harry [Vanda, producer] to mix it. It's amazing to think in those three years, we recorded basically three albums in a six-week period. It's pretty mind-numbing when you look at how albums are recorded today. But it was because of time; that was the maximum amount of time we could attribute to recording. I remember talking to the guys and for the Australian version of High Voltage, they would have to go into the studio after gigs at like midnight to record the album. There's nothing wrong with the band's work ethic. They've never been scared of working hard, let me tell you!

AC/DC have always had the feel of a working-class band.

I think there's an honesty to the band, too. I think people going to gigs can smell "real" about a band, and they can smell when they're getting bullshitted by bands, too.

It's a good thing you had that realness factor; if there had been any bullshit, the last thing a rowdy audience would have stood for is a guy on stage in a schoolboy uniform!

[laughs] It wasn't always a bowl of strawberries for us. When that schoolboy thing started, there was a lot of eyebrows raised. But you know right at the start, the schoolboy persona is the one that won over, but there there was a number of personas that Angus had. He was Zorro for a while, then he was Super Angus with a big "A" and a cape and he used to come out of a telephone box. He had a gorilla suit, he was a fireman for a while with a fireman's hat -- there was a whole bunch of personas, but the one that actually stayed and made sense was the schoolboy. Probably because of his size; he's a tiny little guy.

Getting back to the recording process a bit, how did songwriting happen? Were all the songs written on the road?

No, no, no. Angus and Malcolm may have come up with some ideas and lyric ideas along with Bon, but the songs were all written in the studio. Phil and myself wouldn't really have too much of an idea of what was going to be going on at all until we got into the studio. Angus and Malcolm might have had a guitar riff that they showed us at a soundcheck or something, but then they'd take it into the studio and George would get a hold of it and what would come out would probably be something very different anyway.

Everything was written in the studio, that's the amazing part.

It is amazing given the bands now will take five years between studio albums, especially considering how fast you guys were working, how fast Zeppelin were working, how fast Sabbath were working.

I just finished reading Ozzy's autobiogrpahy, and the first Sabbath album, they went in and recorded that in an afternoon. It's bizarre how now you get a band in the studio for six months doing pre-production, demoing songs. I'd rather be at the dentist! [laughs]

One of my favorite parts of the book was when you talked about the band's tour of Scotland, how you could kind of relax and be tourists for a bit. I imagine there are some good stories of sight-seeing with AC/DC ...

When we first got to Glasgow, we went to a place a little bit out of Glasgow called Stirling Castle, and that's where Mary, Queen of Scots was made the Queen of Scotland in the 1500s. We had Angus and Malcolm going around giving us a lesson on Scots history -- and Scots history back in those days was pretty much England invading Scotland, then Scotland getting the crap beaten out of them and them turning around and beating the hell out of the English and sending them south again.

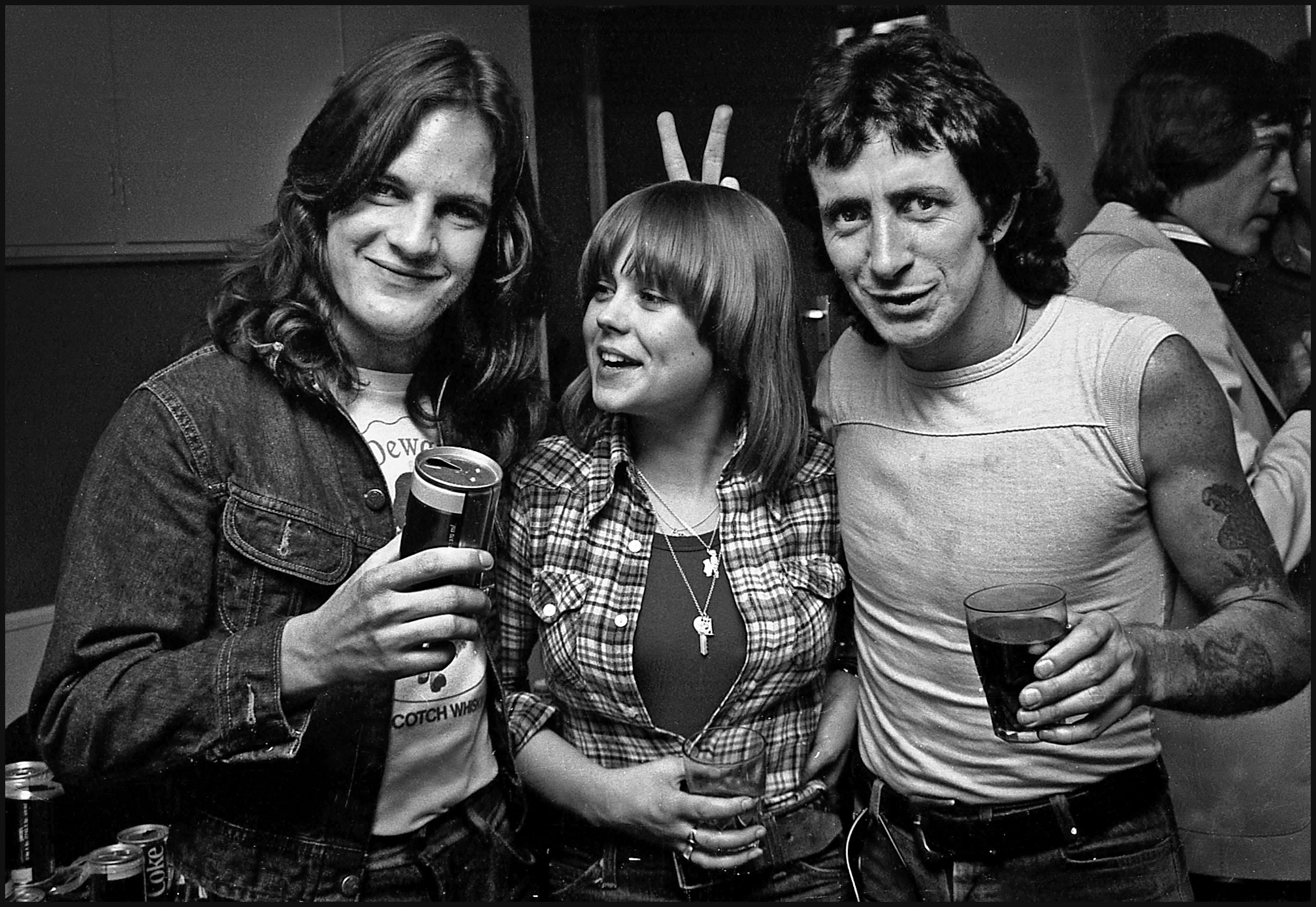

It was just a great vibe watching Angus, Malcolm and Bon reconnecting. I think it's well documented that sometimes Angus and Malcolm aren't the most outgoing of guys. It was really cool getting to see them back in Scotland, because they hadn't been back to Scotland since they immigrated in the early '60s. It was really refreshing to see.

It was during an unplanned break between the European and American legs of a tour when the band was in London that you were let go from the band. Do you think if the break hadn't happened and the band had gone straight to America that you'd still be in the band?

Yeah, I think so. There was a whole bunch of tension around the band at that point with getting kicked off the Sabbath tour and having the Dirty Deeds album rejected by the American record labels. There was a lot of tension, and I'll stop short of saying I was the scapegoat for it, but I think if we had gone straight to the States, it would have been different.

But I don't think it would have changed what happened in the long term. I think what happened would have happened anyway. The way I look at it is that if I was the right guy for the band, I'd still be there.

In many ways, your departure from the band might have been a blessing in disguise as you seemed to get closer with Bon after leaving. Can you share a good Bon story that didn't make it into the book?

Bon was just one of those guys who would constantly be able to surprise you. We used to work in Melbourne at this place called Icelands, which was a small ice hockey stadium where they'd have bands on after the games on Sunday night. Bon was always watching the hockey games and saying, "Oh that's a great game, I'd love to play that game." And we'd say, "Oh right, fine, sure." And then after a gig one night, he said, "I'm going to go get some skates." And I'm thinking, "This is gonna be good," because I thought he'd get on the ice and be like a giraffe on ice.

So he comes back and Bon -- he wouldn't hide things from you, but he wouldn't tell you a lot about his past. So he's putting these skates on and everyone's going, "Oh man, he's gonna go on his ass." And then he just took off like a rocket! I've never seen anyone skate faster in my life, and he was doing twists and turns -- he would have gotten like a 9.9 from the Russian judges! [laughs]

Do you think if you had still been in the band when Bon passed away that you would have been in favor of continuing without him?

Man, I don't know. I don't have an answer to that question. When the guys got back to Sydney -- I can't comment on how they felt, but I would have questioned whether or not to continue. I'm so glad that they made the choice to continue, and I think the transition from Bon to Brian was handled really well. They just got on with the business of being AC/DC, which you would expect them to do, and I've got a lot of respect for how they handled it.

It was really surreal reading how you describe seeing AC/DC for the first time with Brian Johnson. What were your first impressions of him as a frontman?

I think he did a fantastic job. The first gig I saw with him was his first gig in Sydney, and I know as far as the punters go, they consider Sydney the home of the band. So for Brian to go in and to be received as well as he was, and just come across as part of a band, I don't think he could have hoped to be received any better. He was welcomed with open arms. He must have been pretty nervous before the gig, but I gotta tell you, once the band started, you wouldn't know it had been any other way than what it was.

So in recent years you've gotten pretty heavily into collecting vintage guitars and basses. What are some of the gems of your collection?

I've got a few favorites: A '59 Gretsch 6120 in a cowboy case, which is a beautiful guitar. I've got a lot of Fender Precision basses, I'm terminally addicted to Precision basses and Gibson J-200s, because I do a lot of acoustic guitar playing. I'm a blues duo right now with a singer by the name of Dave Tice. I saw Elvis use a J-200 when I was a kid and I thought, "Well, that's the guitar for me." So I just use J-200's when I'm working with Dave.

I have a very nice '52 Tele, which is an original '52 in beautiful condition. I've got a '63 Candy Apple Red Strat I really like. I just love guitars, and they tend to be nice, old vintage things. I've got a real passion for '50s and '60s Fenders. I've had some nice Les Pauls -- a '56 Les Paul Custom, which is a really beautiful guitar. I just love the color, those things are so black! [laughs]

It really is amazing when you think of those vintage guitars from the '50s -- the Les Pauls, Teles and Strats. How many other things that we still use today have barely changed their designs in more than half a century? You certainly can't say that about cars or appliances.

It's amazing Leo Fender engineered all those guitars without even being able to play guitar himself. They're sort of technology-proof. They work so purely. They're like a hammer; a hammer's always going to be a hammer, you know what I mean?

Mark Evans' new book, Dirty Deeds: My Life Inside/Outside of AC/DC, is out this month via Bazillion Points.

Josh Hart is a former web producer and staff writer for Guitar World and Guitar Aficionado magazines (2010–2012). He has since pursued writing fiction under various pseudonyms while exploring the technical underpinnings of journalism, now serving as a senior software engineer for The Seattle Times.