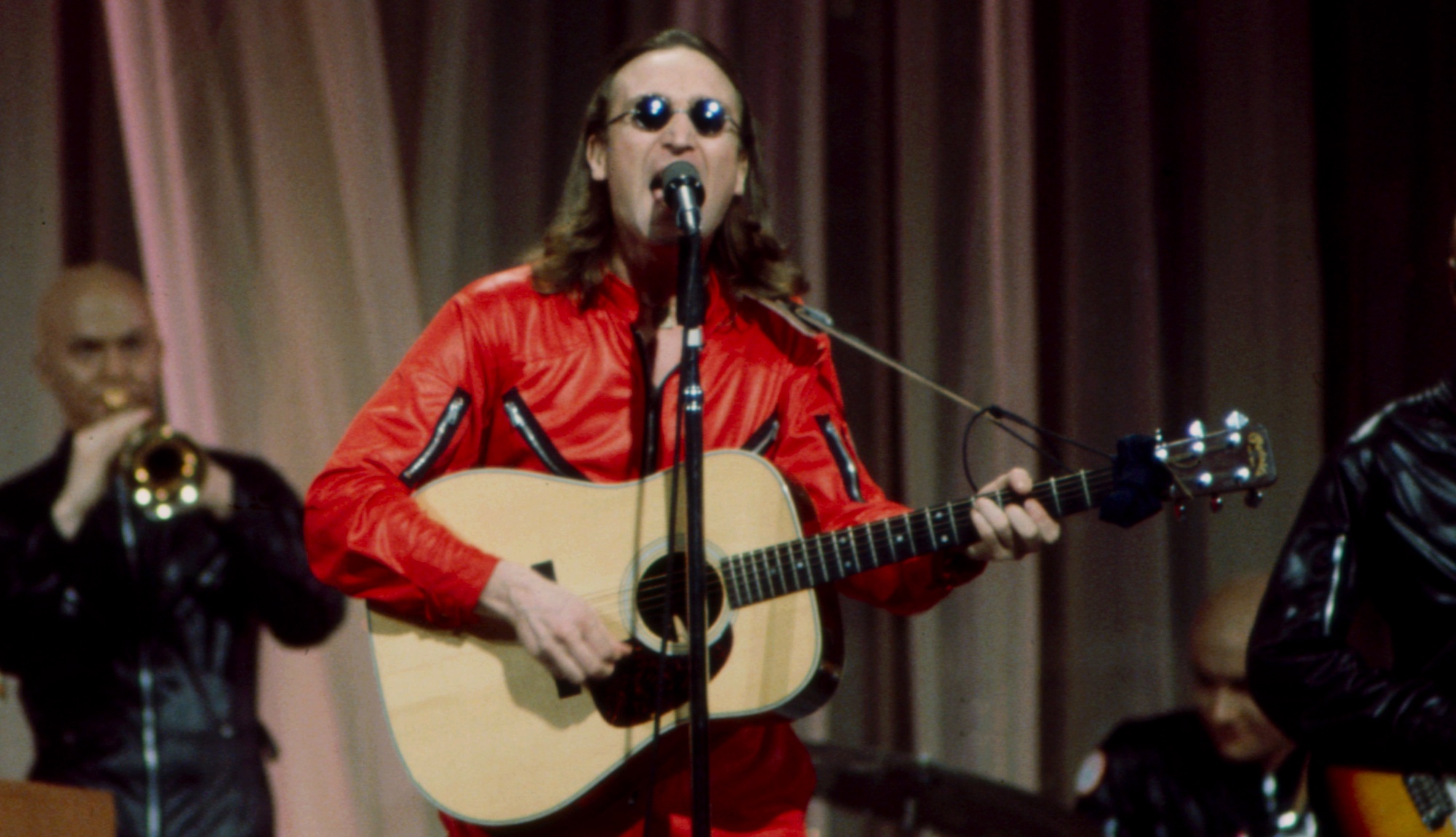

“My work was being compared to Jeff Beck, and they’re crediting Joe Perry. I was so upset. But people who actually listen can tell the difference”: Brad Whitford on the highs and lows of Aerosmith’s 50-year history, and his unique chemistry with Joe Perry

In an exclusive career-spanning interview, Whitford reflects on a tumultuous career in one of America’s great rock institutions, his frustrations at being labeled the rhythm player to Perry’s lead, and what stopped Aerosmith from following up their “piss-poor” final album

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Brad Whitford has been on the move – but he’s finding peace in a pocket of downtime. And he’s going to need it, ahead of Aerosmith’s epic Peace Out farewell tour. Some would say it’s been a long time coming, while others hoped the road would never end.

But none of that matters to Whitford; he’s got a job to do, and for now, at least, all is well. “It’s kind of early on,” he says. “We’ve still got a ways to go, but if rehearsals are any indication of anything, it’s just slamming. It’s sounding so good. I’m just smiling from ear to ear. I love being out there with the guys.”

Whitford has long been a positive and calming influence within the ranks of Aerosmith’s tornado-like existence. But despite his accomplishments, which include iconic solos and heavy riffs, Whitford’s Wikipedia page long led with: “Bradley Ernest Whitford is an American musician who is best known for serving as the rhythm guitarist of the hard rock band Aerosmith.”

If you’ve followed along for the last 50 years, the idea that Whitford is just a “rhythm guitarist” should infuriate you. After all, this is the man who penned or co-penned tracks like Nobody’s Fault, Round and Round and Last Child. Not to mention well-known solos on classic cuts like Kings and Queens and alternating leads with Joe Perry on Back in the Saddle and Love in an Elevator.

These days, though, the misnomer doesn’t bother Whitford much; but during Aerosmith’s heyday, his perspective differed.

“After Rocks came out, Aerosmith was touring England, and I was sitting in a bar in London reading a review of the album in Melody Maker,” he says. “And when they got to talking about Last Child, they started talking about how it sounded like Jeff Beck, which was very flattering. But then I kept reading, and they gave Joe credit for the guitar solo and kept comparing it to Jeff Beck. I read that, and I fucking went nuclear.

“I was just so pissed off. It’s like, here I am, having my fucking work being compared to Jeff Beck, and they’re crediting Joe Perry. It was bullshit, and I was so upset. But I realized stuff like that wasn’t worth worrying about because the people who actually listen – and know what they’re talking about – can tell the difference.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Here I am, having my fucking work being compared to Jeff Beck, and they’re crediting Joe Perry. It was bullshit

Like Perry in the late ’70s, Whitford jettisoned himself from Aerosmith when things got too hot in the early ’80s. And like Perry, despite riding through the darkest valleys of an unrelenting business, Whitford returned to Aerosmith in 1984, holding down the fort since.

If you were to ask Whitford, he’d tell you Aerosmith’s second act was a “miracle,” as is the fact that they’re still here today. There’s no denying that, along with the big hits, huge shows and legendary albums, when it comes to Aerosmith, things have rarely been easy. To that end, without Whitford’s cool-as-the-other-side-of-the-pillow vibe and his tasty licks, the “miracle” that is Aerosmith probably wouldn’t be here today, 50-plus years strong.

Given the bottomless depths of Aerosmith’s valleys and hazardous heights of its peaks, it’s sometimes tricky for Whitford to fathom: “It’s hard to believe it’s been 50 years,” he says. “But there are two versions of that. Sometimes, yes, I can believe it. Other times, I just can’t. Because as I recollect the many things that have happened in 50 years, sometimes it seems more like 75.” [Laughs]

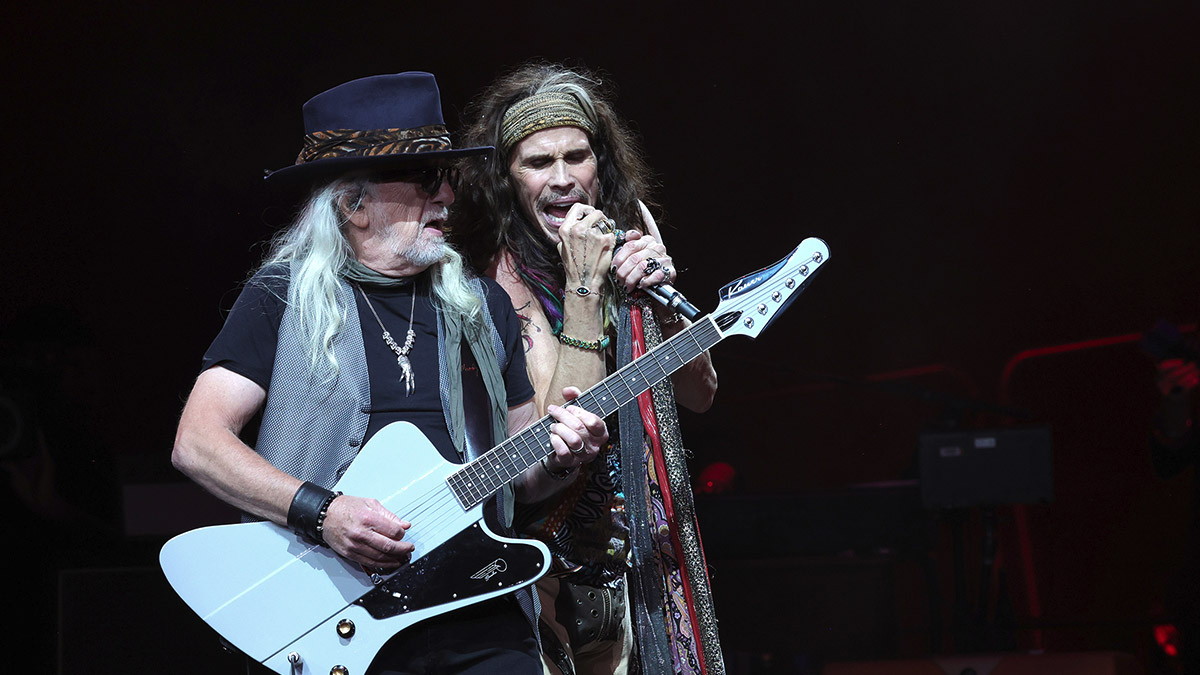

Steven Tyler is the band’s face, Joe Perry his partner-in-crime. But there is no Aerosmith without its second lead guitarist, Brad Whitford. When asked how he balances Aerosmith’s inherent light and shade, Whitford says, “After this call, I’m going to be standing next to Joe Perry pounding out songs all afternoon, and I’ll be as happy as a clam. That’s what still makes this all worth it. But I can’t deny that there was just so much struggle, so much drama and so much pain – and that still comes through sometimes.

“It comes through as not changing the direction of things you want to do because you know you’re not doing that again. It’s like, ‘I know how this ends; I’ve seen this movie before; I can recite every line.’ I’ll take the popcorn and the M&Ms, but you can have the rest.” [Laughs]

As Aerosmith embark on their final tour, remember this: for 50-plus years, Brad Whitford has been the counterbalance to the wild, the provocative, the outlandish and the unbelievable. Through bouts of off-the-cuff bravado meets Berklee-bred brilliance, Whitford has been one-half of what’s amounted to the greatest guitar duo in American rock ’n’ roll history.

For many, Joe Perry embodies what it means to be a lead guitarist. But in Brad Whitford, Perry found his foil through a profoundly intuitive bond that’s bred licks bonded through six-string DNA. Together, Perry and Whitford changed the music world, rupturing it to its core and injecting over-amplified energy that still reverberates.

So, as you’re basking in the glow of Aerosmith’s final performances, remember that as Brad Whitford trades solos, riffs and glances with Joe Perry, as he always has, you’re not only watching greatness, you’re witnessing a lead guitar paradigm that all who came after have tried – and mostly failed – to duplicate.

How did you first become aware of Aerosmith?

“I first became aware of Aerosmith in the summer of 1971. I was playing with a couple of guys who also hung out in New Hampshire, where Aerosmith was born. They would talk to me about Joe [Perry], Steven [Tyler] and Tom [Hamilton], but beyond that, I didn’t know them or anything about them.

“Then I played a show up in New Hampshire around that time, and Joe came to see us play, and that was how I first met him and Tom. They watched us play, and we talked for quite a bit afterward. It was really friendly – just a bunch of young guys talking about gear and all that.”

I don’t think Steven and Joey were 100 percent on board with asking Raymond to step down and Joe asking me to step in. So that was the beginning of the amazing drama and tense moments in and around Aerosmith for me

What led to you joining after Raymond Tabano left?

“About two weeks after I’d met them, I got a call from Joe, and we hung out a bit and got to know each other better. Shortly after, he mentioned something about me maybe joining Aerosmith, and I told him I wasn’t [interested]. I wasn’t jumping up and down or anything, and was like, ‘I don’t even know who you are and what you do yet.’ Then I said, ‘Well, I’d like to see you play something.’ So that’s what we did, and they played great. I loved the show and loved what they were doing, so I said, ‘Yeah, I’d love to be a part of it.’

Considering Raymond went way back with some of the guys, were there growing pains?

“It was all very strange because there was a little bit of a civil war going on, even at the beginning with Aerosmith. Joey [Kramer], Steven and Raymond were longtime buddies growing up in Yonkers, and I don’t think Steven and Joey were 100 percent on board with asking Raymond to step down and Joe asking me to step in. So that was the beginning of the amazing drama and tense moments in and around Aerosmith for me. It was there from the moment I joined, and remains to this very day.”

It seems that particular aspect of Aerosmith is deeply tied to the creative process, along with the chemistry between you and Joe Perry. Was that chemistry also immediate?

“As far as the chemistry goes, yeah, I think it was immediate. But it was also a very unique chemistry, unlike anything else I’ve ever experienced with other guitar players. It’s 100 percent intuitive, where we’ve never sat down in a couple of chairs across from each other going, ‘You do this, you do that.’

It’s always been on the fly from the playing and even with the writing. It was like, ‘Okay, I’ll play this to complement Joe,’ and he’d play something to complement me. That’s just how it works. It’s a unique gift of symmetry that Joe and I have. It’s unlike other relationships with other players, and all I can say is it works, and it’s still a lot of fun.”

How would you say your style differed from Raymond’s?

“I’m not sure how we differed as far as playing, but one thing was that I’d show up. [Laughs] Raymond was a guy who would pull up on his motorcycle 30 seconds before showtime, literally. But Raymond was also one of Steven’s good friends, but there’s a dynamic between Steven and his good friends, which is kind of like how it is between him and Joe; it can be extremely volatile.

“It was the same thing between Steven and Raymond, so I differed from that. But as far as playing is concerned, I was at a much higher skill level at that point, which took the band up a couple of notches, in my opinion.”

How did the volatility inherent in Aerosmith’s ranks impact the sessions for the debut record?

“We were very well-behaved on our first record with Adrian Barber producing [1973’s Aerosmith]. We were just blown away that we had this opportunity, but there was plenty of funny stuff, too. Remember, this was ‘old era’ recording, meaning some of the equipment inside the studio literally was made from cardboard. [Laughs]

“We had EQ systems that were like out of Dr. Frankenstein’s laboratory, bass and treble knobs the size of small clocks, and all sorts of gear that seemed like it came out of the 1940s.”

We quickly realized that while we’d be loosey goosey during rehearsals when the red light came on, we became stiff as boards

And how did that impact the sound of the record?

“We did the record in a small room where we set up and recorded live. And the first thing that became apparent, which is really funny, was we had the old-school Hollywood studio’s green and red light outside the soundstage door. We’d be inside the room, and this red light was inside our room, and it would go on when the tape was running and recording. So Adrian would yell, ‘Okay, we’re ready to go,’ and I can only speak for myself, but I was like, ‘Oh, God, don’t fuck up, whatever you do!’

“But it was rock ’n’ roll, you know? You’ve just gotta shoot from the hip, and we quickly realized that while we’d be loosey goosey during rehearsals when the red light came on, we became stiff as boards. But we got around that, had fun and did what we could with the limited opportunity for overdubs that we had.

“ We had to be very creative because it’s unlike today, where you have limitless ways to fix things. Back then, you had to wait for the tape to rewind. But the end result was just magic.”

Joe has echoed your sentiment that there wasn’t a lot of conversation about who would do what. But he did mention that an effort was made to create contrasting sounds using different guitars. Is that your recollection, too?

“Yeah, that’s true. We wanted to create different dynamics through different guitars and the sounds they could make. With the first record, for example, I think the difference in sounds is pretty apparent. I believe Joe was using his black Strat, but I couldn’t tell you what year it was.

“These days, whatever it was, it would be an awesome vintage Strat, but then it was pretty much a new Strat. It was probably a couple of years old, but it sounded great. As for me, I used my ’68 Les Paul goldtop, which had P-90s in it. We used two guitars on the whole record, which is crazy. Some of the tone we got was pretty wild, and we haven’t strayed too far from that.”

How so?

“Even today, my thought is still based on the belief that a guitar to a cable to an amp is the best sound. That’s the only way you’ll know what a guitar and amp truly sound like and the only way you’ll find out if a guy can play. It’s all between the heart and hands, you know?”

After you and Joe handled the guitars yourself on the first record, Steve Hunter and Dick Wagner were called in while recording Get Your Wings. We know they played on Train Kept A-Rollin’,” but was there more?

“Steve and Dick played on Train Kept A-Rollin’. By the way, S.O.S. (Too Bad) is Steve Hunter, too. And he played those [parts] fucking incredibly beautifully. I don’t think I was on Lord of the Thighs either, but I remember playing the last little solo section of Seasons of Wither. There wasn’t a whole lot to it. And then Same Old Song and Dance was Dick too.”

What led to that?

“By that point, all the basic tracks were cut at the Record Plant in New York City, and our producer, Jack Douglas, was talking to his boss, Bob Ezrin, the brains behind Alice Cooper’s records, and probably some management people at our record company, too. Jack said, ‘Listen, I’ve got these great tracks, but they need superior leads over them to sell them.’

“Joe and I had tried multiple times to do something interesting, but I wasn’t there yet, and neither was Joe. And if you listen to Steve Hunter’s stuff from that time and the level he was able to perform at, it’s incredible. So they decided, 'Let’s bring in the Alice Cooper team and see what they can do.'”

Were you and Joe frustrated by that decision?

“It was Jack who had the difficult task of breaking the news to Joe and me, and of course, that went down like a lead balloon. [Laughs] At first you fight, and you’re a little bit angry, and then you get sad to where you’re like really bummed out that you can’t do it.

“And the thing was that we’d done some good stuff and could play good stuff, but the tracks required some real finesse, you know? But I mean… listen to Train Kept A-Rollin’ today; those are some fucking genius rock leads. That was some great stuff and probably some of the stuff that they were most proud of out of anything they’d done. That solo is blistering.”

Were you there while he recorded it, or did you hear it after the fact?

“I had the unique pleasure of being in the studio when Steve came in to cut the Train solo. It was fucking amazing. He came in with a little Fender tweed, with a ’57 Les Paul Junior with a P-90. He set the amp down, grabbed the guitar, they started rolling tape, and Steve did several passes. Then Steve says, ‘Okay, I think I’ve got it now,’ and then he did his final pass, which was just mind-blowing.

“I listen back to it even today, and it’s still a lesson on guitar. Since then, Steve has had so much influence on me as a player because his playing is very much up my alley. I continue to learn some of the nuances in his playing. And Dick was a bit more like Joe, so it worked out very well.”

After that experience, did your and Joe’s approach change during the recording of Toys in the Attic and Rocks?

“A lot of the guitar sounds we recorded were done through such a simplistic approach. It’s something I can’t make work today because it takes a lot of work and searching around. But pretty much all of it was done with 100-watt Marshall half-stacks.

“We had all these great vintage Marshall amps full of greenbacks; we just plugged straight into those. That’s what you hear on Toys and Rocks. For us, it was all about the attitude. The approach was about making it tight and having the guitar parts pop but also groove. That’s what made it for us. That’s the sound and the attitude.

“But there was a fair amount of precision on those rhythm tracks. There’s a cool Japanese import of Rocks that’s just the guitar tracks. I listened back to it, and I had to put a diaper on; I loved it so much. Have you heard it?”

I have. It’s outstanding.

“It really is. And another thing about the Japanese version is the drums are turned up, which is a story in and of itself. When we made Rocks, certain people behind the mixing console weren’t going out of their way to make the drums sound good. Our drummer had a certain amount of attitude, which wasn’t really appreciated. [Laughs]

“Jack Douglas and Jay Messina were the kind of guys that if they didn’t have a lot of love in their hearts for someone, they’d take it out on them. And Joey was famous for turning people off with his attitude, so they turned the drums down. So there’s a little personal vendetta that no one knew about. I honestly don’t think the rest of the band even knows this. [Laughs]”

There’s an argument to be made that the attitude within Aerosmith’s ranks is part of what made the ’70s era great, no?

“Well, yeah, but what was nice about that period was that we could still do what we call ‘practice.’ We rehearsed a lot, so we knew exactly what we were doing, unlike later albums where we’d have to come up with stuff while there were no vocals or anything.

“We’d have no direction and no real idea what we were gonna do. And Steven was usually very involved in arrangements, but if he didn’t know what the fuck he was going to do, he couldn’t have anything to say about the arrangement.”

You can hear it on some throwaway tracks on later records where there are guitar riffs, and then there’s some stupid yodeling from Steven because he never did his work

I can imagine that being difficult to navigate.

“You can hear it on some throwaway tracks on later records where there are guitar riffs, and then there’s some stupid yodeling from Steven because he never did his work. I would have loved to have B-sides like the Stones, but we didn’t because we weren’t mature enough or ready to admit it or able to get Steven to do the work he was supposed to do.

“After Toys and Rocks, that’s what we were up against. The bucks and the drugs started to flow, and a lot of it was such a waste. But right now, we’re rehearsing, and we’ve got a list of about fucking kickass songs out of all that. So I would never complain; I’m just telling you the truth. What we have is great, but unfortunately, there was a lot of wasted tape.”

Do you feel Aerosmith reached their full potential?

“I think we were at our full potential on day one. I don’t know if we realized it, but I say that because of one guy and one song, and that’s Steven bringing in Dream On. I don’t know what it is, but to this day, it’s still everywhere. And Steven had that in his back pocket when we started the first record.

“So when we talk about potential, looking at Dream On, Aerosmith was sitting on a nuke. And like I said, we went through Toys and Rocks, and so much of it slipped away. But there were still some shining moments here and there.”

When we talk about potential, looking at Dream On, Aerosmith was sitting on a nuke

Given your chemistry with Joe, was it difficult when he walked away during the Night in the Ruts sessions?

“I can only tell you what I experienced, so I can’t speak for anybody else. But Joe left, and I said, ‘Okay, now what are we gonna do?’ So we auditioned players, and there were a bunch of great guys, but in the end, we chose Jimmy [Crespo]. And looking back, Jimmy had the same look as Joe, with dark hair and a very dark mood about him.

“But don’t get me wrong – Jimmy is a great player. The dynamic between Jimmy and me was very different from how Joe and I worked. Jimmy and I would sit down and work things out in fine detail. Jimmy was very into that, and I loved it, so I loved playing with him, too.”

What was the point of no return that led to the end of Aerosmith’s first era?

“After Jimmy came aboard, we were trying to do a new album. So the record company said, ‘That’s fine. What is it? What are you going to do?’ But we didn’t even have a demo, so the plan became that in the summer of 1980, we were going to go in and work on trying to make three demos.

Steven would show up, and they’d carry him into the reception room, and he’d be on the chair or the couch like a bag of potatoes, and that’s where he’d stay. We were doing this day after f**king day

“And at that same time, I was writing with Derek St. Holmes for the first record we did. I was working on that and had about four weeks before I needed to head back to New York and be with Aerosmith at The Power Station.

“So I get up there to New York City, and it’s me, Tom and Joey showing up each day at the studio, and we’re waiting for Steven to arrive and hopefully come up with something. And then he’d arrive, and we’d literally do nothing. Steven would show up, and they’d carry him into the reception room, and he’d be on the chair or the couch like a bag of potatoes, and that’s where he’d stay.

“We were doing this day after fucking day, and the ‘fucking’ just came out because I still remember how pissed I was. I was like, ‘This is a joke. We’re spending money on this.’”

Is that what led you to quit?

“I decided to take some time off and go home to Massachusetts for a couple of days. After that, I was supposed to go back to New York, but I was a total wreck. I got to Logan Airport in Boston, called our manager David Krebs, and said, ‘I’m done. I can’t do this. You will not see me in New York.’ I hung up the phone, and that was it.

“I felt like I’d just moved a mountain off my back. I felt like I could breathe again. All this weight was off my shoulders, and I honestly didn’t care. I was also happy about the Whitford/St. Holmes thing. It was productive. It worked. It was real. It was tangible. It wasn’t this thing that had just slipped out of our hands, which was sad, ugly and covered in drugs.”

No-one knew how gigantic Walk This Way was going to be. And I’ve always believed that the spirit of collaboration broadens the scope of anything

Do you feel Columbia Records properly supported Whitford/St. Holmes?

“I look back on that stuff, and yeah, I think they were gung-ho about it. They were ready to go with it. There were two-page ads in Billboard, and a lot of people seemed to really love the record.

“Budgets went down, and there was only a finite amount of money that could be used for promotion. But we had a pretty good start and a lot of fun. I still love that record. I still listen to it along with the new one we did side by side, and I think what we had is pretty unique.”

What led to the classic Aerosmith lineup getting back together in ’84?

“The whole time I was doing the Whitford/St. Holmes thing, and then when I started playing with Joe again, I’d be in the studio with other Leber-Krebs clients, and they’d say, ‘When are you going to get back together with Aerosmith?’ And I always had the same story: ‘I’ll tell you what – it comes down to Steven Tyler and Joe Perry. If they can find some way to bury their hatchets, I would follow them.’ But I honestly thought it would never happen.”

But it did happen. Going in, did you have concerns about being able to contend in a scene that had changed so much?

“I don’t think I really got that far ahead. I was so elated to be working with the guys in Aerosmith again. Being back with the guys was refreshing, and the fact that we were all in the same room together again and rehearsing those songs was incredible.

“We didn’t have a grand plan beyond getting to that point, so we didn’t really think about the level of success we could have. I was just so pleased that things seemed to be on some kind of road to somewhere again.”

Was it a surprise to see Aerosmith’s second wave of success come by way of a crossover collaboration with Run-DMC on Walk This Way?

“Of course. No-one knew how gigantic that was going to be. And I’ve always believed that the spirit of collaboration broadens the scope of anything. So I definitely thought it was a very cool idea.

“The only problem was that it was originally proposed to us as something the whole band was going to do, but then it was only Joe and Steven who went into the studio to do it with them. And truly, that was all that was needed, and it was done right. But the rest of us were kind of miffed about it at the time.

“We disagreed and thought we should at least sit on the couch in the control room and be a part of it. But it wasn’t an artistic decision… probably more of a budgetary decision. But looking back, it was just such a huge moment in music history from that period.”

The record that followed, Permanent Vacation, catapulted Aerosmith into the heart of the MTV era. I’ve always loved your leads on the title track. Any memories?

“Well, thank you. I appreciate that. Recording it is a little blurry, but I recall wanting to go for a sound that was a little more like what Stevie Ray Vaughan was doing. I believe I did that by using a Strat, so it was more a matter of going in knowing how I wanted the solo to sound.

“It’s kind of like when you put a song on, and you hear it, and you like the sound when you listen to it. I knew the sound I wanted, grabbed one of my Strats and did the solo.”

The kids who were listening to us didn’t care about our amps; it was about having good hair

Did Aerosmith feel comfortable during the MTV era, given its status as an “older band?”

“A story that puts that into perspective had to do with Dude (Looks Like a Lady) and what inspired it. For as much as Steven, or any of us, looked like young girls with all the makeup and the hair, Steven was really pushing the envelope. [Laughs] And that’s where the impetus of that came from.

“I think Steven had actually said to himself, ‘Dude looks like a lady.’ You had younger bands like Mötley Crüe doing the glam thing and even other older bands like Kiss, along with us all being listened to by young kids. It was an interesting time and kind of outrageous. The kids who were listening to us didn’t care about our amps; it was about having good hair. [Laughs]”

You mentioned the unspoken chemistry between you and Joe, which seems devoid of ego. An example is your alternating leads heard on Love in an Elevator. How does something like that come together?

“Yeah, that’s true. The thing about Joe is he likes to construct his solos beforehand, whereas I shoot from the hip with just about everything. I was always the one-take, ‘get it on the first try’ guy. So with most of the solos – and this was the case with Love in an Elevator – Joe would listen and then try some different things.

“I’d typically come up with an opening section that would then break down into a rhythm part and lead into Joe’s entrance. And when Joe comes in there, that part he does – wow, it’s just so cool, right? It’s classic and such a great lick that he came up with. It’s so badass. So I’d just shoot from the hip or throw out some ideas I may have had in my head. A lot of what you hear is what came right off the bat.”

I’ll tell you what – I cannot play like Joe Perry. I can’t do it

There are no defined roles between you and Joe, but people still incorrectly label you the rhythm guitarist and Joe the lead. Has that been frustrating for you?

“It bothered me for many years, but then I realized, ‘Okay, anyone that thinks that is someone who simply does not listen.’ And you’re right; we don’t have defined roles; we’re both just guitar players in this band. If someone specifically labels us as one or the other, they’re not listening. That’s their problem. It’s not my problem that they can’t hear the difference.

“Sure, there have been times over the decades when Joe and I can imitate each other, but that’s only because we’re huge fans of each other’s styles. But I’ll tell you what – I cannot play like Joe Perry. I can’t do it.”

What makes Joe unique?

“Joe has such an elite sense of timing, rhythm and note choices. I don’t do that. I’m more Berklee-inspired. I’m always thinking about intervals, scales, chords and how they’re supposed to fit together.

“Joe is very different; he’s not schooled. So sometimes it doesn’t work for him, and sometimes he’ll try playing over something, and he doesn’t realize it’s not pentatonic, but he does find notes, and while he doesn’t always know how or why it’s working, he doesn’t really care because it does work. And truthfully, that’s a real gift that Joe has.

Joe has such an elite sense of timing, rhythm and note choices. I don’t do that. I’m more Berklee-inspired

“I doubt Robert Johnson knew what fucking intervals he was working within a musical sense or what that looked like on paper – but who gives a shit? It’s the same with Joe, so who cares if he knows what he’s doing, because what he’s doing is fucking killer. Joe is gifted, talented and uniquely his own, which is rare in a world where there are tens of millions of people with guitars in their hands.”

It’s probably a generational thing, with younger fans often feeling Get a Grip [1993] is Aerosmith’s definitive album, while older fans tend to choose Rocks [1976]. Which is it for you?

“I think you’re right about the generational way of thinking because, to me, it’s Rocks. If I had to go to a desert island with just one of our albums, Rocks would be it. So put that on my gravestone – it’s Rocks. I hear that, and having been a part of that and understanding the vibe and the spirit that went into that, I know it’s all in there.

“But that’s me. I don’t know what other people think. Everybody will always have a different opinion, especially the guys in the band. But for me, Rocks is the defining moment for us.”

And where does Get a Grip fall within the Aerosmith canon, considering it netted the band a Grammy and a massive success in the thick of the grunge era?

“It was huge. And with the grunge thing, we were never gonna let the flag for rock ’n’ roll come down. When Kiss decided to do a disco record in the late ’70s, we were like, ‘Oh my God.’ We said, ‘Is this really where it’s going? It’s all slipping right out of our fingers.’ But we’ve never been a band that would let go of it. So with Get a Grip, we were just so proud of it and how well it did. So it lives on.

“But as far as punk and grunge, maybe it’s because I’m a bit of a Berklee-head, but it took me years to appreciate that. It wasn’t until years later that I realized that bands like the Ramones were right in my pocket.

“I don’t know what I was thinking; I wasn’t into it then. But there’s so much freedom in the performances, and I love how those bands went for it by sticking it to the people who deserved it.”

Aerosmith have released just four studio albums in the 30 years since Get a Grip. Why is that?

“I cannot put my finger on it. I guess I’ll call it out-and-out laziness. Because I’m still writing, and I still play guitar every day. I don’t know… I can’t figure out what happened. Other than maybe frustration because sometimes it was like a woman being in labor and not wanting to do that, I can’t figure it out.”

Is the desire to make new music still there?

“Maybe six or seven years ago, we were on the phone having a meeting with everybody, and the subject came up. So I asked, and I had a very simple plan; I said, ‘Let’s pick a city or studio, and we’ll book it for one day; it can be a day that works for us all, maybe a Saturday.’ I said, ‘Everybody can fly in Friday and Saturday morning; we have an open-ended session with one goal: to make a song and have one demo.’”

That sounds reasonable, given the band’s recording history.

“Right. I play every day. I pick up the guitar, and out of my hands comes something that I’ve never played before. Maybe it would be an intro or even the main riff. I know Joe Perry and Tom Hamilton do that, too. So I said, ‘We go in and come out with at least a one-song demo. I don’t even care if Steven just sings ‘blah, blah, blah.’’

“I said that, and they just said, ‘Oh, we can’t do that.’ I was in shock; it’s not rocket science for us. It’s not impossible, and we’ve done it before. I don’t care if the song was a piece of shit; it was to be an exercise in creativity. But nobody wanted to fucking do it. So I threw my hands up in the air, and that’s where my hands remain to this day.”

Is Music from Another Dimension! Aerosmith’s final studio record?

“Yeah… I think that it is. And that’s sad because, I hate to say this, and we were talking about the idea of potential earlier, but that was just a piss-poor record. It’s like… where is that certain something? I guess it got left behind somewhere.

“I think there are just a lot of scars, I guess I would say. And, God knows, we love the shit out of each other; we’re brothers through and through. But there’s a lot of dark stuff from the past, and I guess, like with anybody else, it’s hard to get past that.”

Looking back on 50 years, how do you reconcile the good with the bad?

“Those emotional bruises don’t go away. When you lose a part of that, it’s not something that goes away. And that’s how close we are; Aerosmith is a very close-knit family relationship. We’re extremely tight and deeply bound together. But when you have that many disappointments over time, it really hurts. I’ve let go of as much as I can. And in doing that, my goal is to always bring positive energy and love to whatever we do.”

Do you still feel as close to the guys as you once did?

“Well, there’s a vacuum, and like I said, I love all the guys; we have great affection for each other. We all have that; it never went away. And oftentimes, we’ll be standing in a little circle while we’re rehearsing or just talking, and Steven will say, ‘Can you believe we’re still doing this?’ And we’re like, ‘No. It’s honestly unbelievable.’

“There’s more appreciation for the higher powers as we go along because it’s truly a miracle that we’re still here doing this. And we tried to keep it the original five for as long as we could, and even though Joey isn’t here on drums for this last tour, we still have so much love and respect for each other. That’s something that will forever be frozen in time.”

Bands often announce farewell tours, only to return a few years later. Is this really it for Aerosmith?

There shouldn’t be any drama; we humans have enough shit going on. So when we finish this tour, that’s going to be it

“In my mind, it’s not possible to keep going. I don’t bullshit anybody; I just don’t do it, and sometimes that upsets people. That’s just the way it is. People have to be willing to accept that. And I was probably the last person to sign on for this tour because even though this is a multimillion-dollar business, the reality is you’ve got to work awfully hard to end up in a good place financially.

“But it’s not really rocket science, and it should always be more fun than you’ve ever had, right? There shouldn’t be any drama; we humans have enough shit going on. So when we finish this tour, that’s going to be it.”

Who is America’s greatest rock and roll band? Kiss or Aerosmith?

“That’s a really tough one. I think you’d have to come up with things to sort that out categorically. But what I love about Kiss is they can go on forever because of their makeup. So that’s one aspect of what they do that’s very different from what we do. But the last Kiss show I saw was absolutely brilliant, and there are days when I’ve come off the stage with Aerosmith and just went, ‘Wow. What the hell was that? How do I recreate that?’

“Some shows are great, and you search for ways to do it again, but that’s the beauty of this. You never know when you’re going to have one of those supernatural shows. It’s not something you can rehearse; a lot of it comes down to the band and the audience. Sometimes you end up with a magic moment you can’t predict; I think all the good bands have those moments. We have them, and so does Kiss. I don’t know how you choose.”

Andrew Daly is an iced-coffee-addicted, oddball Telecaster-playing, alfredo pasta-loving journalist from Long Island, NY, who, in addition to being a contributing writer for Guitar World, scribes for Bass Player, Guitar Player, Guitarist, and MusicRadar. Andrew has interviewed favorites like Ace Frehley, Johnny Marr, Vito Bratta, Bruce Kulick, Joe Perry, Brad Whitford, Tom Morello, Rich Robinson, and Paul Stanley, while his all-time favorite (rhythm player), Keith Richards, continues to elude him.