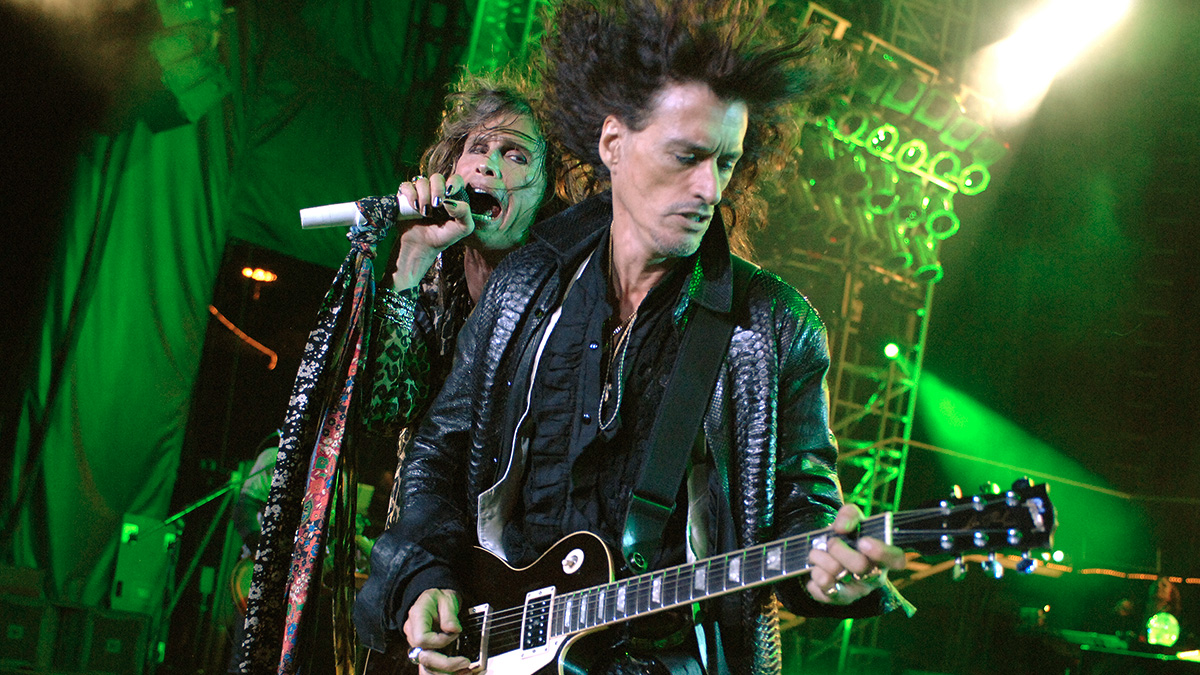

“In my mind, we could be like the Yardbirds in those rare times when you had Jimmy Page and Jeff Beck together. That’s what we wanted Aerosmith to be”: Joe Perry reflects on 50 years of America’s greatest rock band

In this exclusive interview, Perry looks back at every era of the rock institution: how their rapid rise ultimately took its toll, why Van Halen caused him to quit in the ’80s, how he and Steven Tyler reconciled their differences, and why he finds himself playing Strats more than Gibsons

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Joe Perry has still got it. That much is true. Considering he’s 73, you’d think he’d be slowing down, but here’s the thing – he’s not. Perry is as nimble-fingered as ever. And as I prepare to settle in for what amounts to a two-hour call with the veteran gunslinger, it becomes apparent that Perry is not only nimble but busy, too.

“I’ve been running around all week getting ready for the [Hollywood] Vampires tour,” Perry says. “It’s been crazy. It blows my fucking mind how busy we’ve been. When we started, I never expected to be this busy, but it’s been great. I’ve got all my guitars loaded up, and we’re ready to go.”

Indeed, those 73-year-old hands still traverse the fretboard of his array of well-loved Fenders and Gibsons with tenderness and ease. Anyone who has seen Perry live lately will tell you that his swagger remains, only to be matched by an unmistakable tone that – for 50-plus years – has defined America’s greatest rock band, Aerosmith.

And what of that tone? What’s more, what of the notion that Aerosmith – which after 50 years of breakups, shake-ups and extended pauses, is still composed of Steven Tyler, Brad Whitford, Tom Hamilton, Joey Kramer and Perry – is America’s greatest rock band?

As for Perry’s tone, boy, it’s sweeter and sleazier than ever. Of course, gone are the drugs, drinks and drama, but make no mistake, Perry can still summon the ravenous ghost of his stage-struttin’ past with ease.

Now unencumbered and staring the end of Aerosmith’s road down, like an outlaw would the barrel of a gun, there’s nothing left to prove. For Perry, though, the end doesn’t mean complacency. What he’s built is too important for that. And so it’s not over until he says it is.

He’ll show up and burn it down like he always has. And it’s that same fire that leads Perry to sling his trusty “Burned Strat” over his shoulder, whip his grayed and frayed hair back, take a breath and swagger with utter confidence while wailing away at the riffs and solos that made him a legend.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

I guess, maybe if I didn’t drink the whole decade of the ’70s away, things would have been different. But beyond that, I’m proud of what we’ve done; there are no major regrets

Perry has seen it all – sometimes (but not anymore) through a hazy lens of too many illicit substances. And there’s an argument to be made that he’s forgotten more than he remembers.

Not that Perry harbors many regrets when he thinks back, saying, “It’s too hard to pick any one thing, you know? But I guess, maybe if I didn’t drink the whole decade of the ’70s away, things would have been different. But beyond that, I’m proud of what we’ve done; there are no major regrets.”

The ugliest side of the music business saw Perry fall into a pit of his own making, only for him to climb out and dominate with more turbo-charged machismo than before. No, he was never the fastest gun in the game, nor was the technical side his bag. But Perry didn’t need to be; no-one can take that from him. Nor could they endeavor to be him. He’s that original.

Still, when he thinks back on his origins, Perry, as is his trademark, remains soft-spoken and dutifully humble, “I really didn’t have a lot of guitar players around me growing up. I didn’t grow up in a musical family, and I didn’t come from a town with all these hot guitar players. I didn’t have many examples, which is probably why I play right-handed even though I’m left-handed.

“I didn’t know there was such a thing as a left-handed guitar until much later. It wasn’t until I got going with the guys and we moved to Boston that we started to hear other bands and stuff. That’s when I began picking up a few things along the way.”

In a world where sameness has become the standard, Perry chooses to stand out even at 73. Maybe it’s because that fire still burns, or perhaps he’s never done it any other way but his own. Regardless, when Perry hits the stage, all eyes are on him. And considering he’s shared that stage with Steven Tyler for 50 years, that’s saying something.

“Steven and I are the type of guys who like to run through the woods with BB guns,” Perry says with a laugh. “And for all the ups and downs when we were away from the band, Steven and I have always been just like brothers.

“We’ve had so many adventures together, like SCUBA diving in Maui, where we went down to see a shipwreck. And when we were out playing Vegas, we went out into the desert and paraglided with a parachute. I still love the guy like a brother. We’re closer than ever, and I’m not just saying that, either. It’s true.”

Relationships and resurgences aside, Perry is facing the end of a long road with Aerosmith. But that’s alright because, for now, he’s still got it. When you think of a quintessential rock guitarist, a few players come up, but there’s more than a puncher’s chance that one of, if not the first name that springs to mind, is Joe Perry.

I’m just so thankful to the fans because without them we wouldn’t still be here. Our career has been a blessing, and sometimes I still can’t believe it

Thinking on the significance of Aerosmith’s final tour – and if this is truly it for the band – Perry says, “I really do think it is it. If you look at how old we are, the fact that we can still go out and play as a band is pretty remarkable.

“It’s sad that Joey [Kramer] can’t go out; he’s given everything he has to give physically, but the rest of us can still do it [Back in May, Aerosmith released the following statement: “While Joey Kramer remains a beloved founding member of Aerosmith, he has regrettably made the decision to sit out the currently scheduled touring dates to focus his full attention on his family and health.”] But we never want to get to the point where we feel like we can’t play the way we used to. So yeah, I think this is it.

“I’m just so thankful to the fans because without them we wouldn’t still be here. Our career has been a blessing, and sometimes I still can’t believe it. When we started, I never imagined we’d be here doing this 50 years later. To have it be the same guys out there together at the end is amazing, and I’m very thankful for that, too.”

What was your vision in terms of the guitar sound that’s become synonymous with Aerosmith?

“When I was growing up, my early years of guitar in terms of sounds that I heard before the British Invasion were shaped by what I heard on pop radio. You had guitars that were fairly clean-sounding and didn’t have a lot of heavy tone. But then, when the Beatles came out, guitars became prominent.

“I could hear the separation of the notes better, which, again, were fairly clean. Then when I was around 14 or 15, I started listening to the Yardbirds, which had a bit more distortion. But there wasn’t much that they were doing; it was more that they had some hot amps, a couple of tricks and maybe a foot pedal or two; that was it. It was more about turning the amp up and listening back to the guitar sounds, you know?”

I always liked the guitar to be a little cleaner because I liked being able to hear the tone of the guitar

So that combination of clean and distorted tones was the basis for you, then?

“I’d say so, because Brad [Whitford] and I were pretty much straight into the amps early on. It just seemed to be the right sound, you know? But I’ve always been the type of player ready to try something new. And being in a band like Aerosmith, it’s about the song and what works right, and then adapting to that.

“I always liked the guitar to be a little cleaner because I liked being able to hear the tone of the guitar. Hearing the tone was important to me; even if there was some distortion or a little hair on it, I still wanted to hear the difference between a Strat and a Gibson.”

What sort of gear were you working with leading up to the recording of the first Aerosmith record in 1973?

“Back then, I was pretty much using a Strat that I’d bought right off the wall. The way it was early on was if I needed a guitar, I just went out to a guitar shop and bought one. I wasn’t thinking about whether old guitars sounded better than new ones. Even my first Les Paul was brand new; I bought a ’68 Goldtop reissue right off the wall.

“But I wasn’t hip to what sounded better and this and that. I remember reading about the Beatles talking about their guitar strings, and they didn’t care about gauges; they just wanted new strings because they sounded better. They were more about the sound, and that’s kinda how I thought about it, too.”

Looking at a track like Mama Kin, how did that approach shape that song’s riff?

“That riff, in fact, was written by Steven [Tyler]. But by that point, Tom [Hamilton] and I were really into the English bands; we were listening to a lot of that and checking out the guitar tones. And we had played some of it for Steven, who sat down with a guitar – even though he’s not a great guitar player – and wrote that riff. So Steven came up with the Mama Kin riff, but we immediately took to it.”

You mentioned the Stratocaster, but did you still have that ’68 Goldtop during the recording of Aerosmith’s first record?

“No, I had actually sold the Goldtop by that point. I remember I had a black Strat from ’70 or ’71 and a ’58 Les Paul Junior with a P90 pickup, too, which I got by selling the Goldtop. Those were my main guitars for the first record. I really liked the P-90; it sounded great with this 50-watt Ampeg I had, which rounded out what I used.

“I didn’t start using Marshalls until the second record, so the Ampeg was probably pretty against the grain for the time. It wasn’t the sound I was expecting to get when I went into the studio, but at the time, I didn’t know enough to change what I was doing. It ended up sounding great and worked out really well.”

How did having more experience inform your approach on 1974’s Get Your Wings?

“The first record was a major learning experience for all of us. But for me, it was like, 'Okay, let’s get in the studio, and I’ll work on getting the guitar sounds I’m looking for along the way.' But I learned quickly that you only get out what you put in, meaning whatever you put into the microphone – that’s it, baby. So, except for a little reverb, there’s no other magic in the studio. And obviously, recording to tape and all the minutiae that goes with that presents challenges, too.”

I assume digging deeper into the technical side of it only made you a better player.

“It wasn’t until the third or fourth record that I began to get into the engineering part of it. I’d go into the studio early and end up staying late with our producer, Jack [Douglas], learning what gear did and how that all plays into everything while you’re recording. But going back to Get Your Wings, my mindset was, ‘Okay, I gotta get the sound right before I even walk into the studio.’

“That was a change from what I’d done on the first record. So it really was a learning experience, which was important because when we went in to record Toys in the Attic [1975], we had to write a good three-quarters of that material in the studio.”

I liked the clarity of Strats. But don’t get me wrong – I played Gibsons, too; I loved the fat neck and fat frets, and I loved the way they handled

What necessitated that?

“When we signed with Columbia Records, we had a bunch of songs that we’d been playing in clubs, and we recorded most of that on the first two albums. So when we went in to do Toys in the Attic, we only had a little bit of that old material left. We wrote some stuff in the studio, which gave us the backbone of maybe five or six good songs.

“We got pretty comfortable with that process and learned to use the gear to our advantage. That’s why our first two records didn’t take off; we had to learn about the dynamics of what it takes to make a good record.”

How did you come up with the riff for Walk This Way?

“I was probably using my older sunburst Strat, which was pretty beat up, when I wrote that riff. I remember being at a soundcheck in Hawaii, and I was thinking about the stuff I was listening to, which was a lot of things by the Meters, James Brown and that type of stuff.

“I loved that stuff because it gave me the feel of where rock music came from, you know? Anyway, we’re at soundcheck, and I told Joey [Kramer] to lay something down that was kinda like what I was listening to, and I started playing this riff and fleshed it out right there at soundcheck.”

That was an interesting song because many of our songs’ melodies come from the guitar riffs, but not so much with Walk This Way

Did you know you had a hit right away?

“Not immediately, but I liked it. And so, when we brought it to New York during the sessions for Toys in the Attic, Steven and I started working on it together. He added some lyrics that fit the melody, along with a little bit of blood and sweat, and it all worked out. That was an interesting song because many of our songs’ melodies come from the guitar riffs, but not so much with Walk This Way.”

Did you also use that same sunburst Strat for the Walk This Way solo?

“Yeah, I did. I distinctly remember just kind of standing there, probably next to either a ’50s, ’60s or early ’70s Marshall – it was so long ago, it’s hard to remember – and I came up with the solo. I had some kind of distortion pedal, maybe a [Maestro] Fuzz Tone, and I just stood in front of the amp with the Strat and recorded the solo.”

These days, you’re more associated with Gibsons, but Strats played a significant role early on. Why was that?

“I liked the clarity of Strats. But don’t get me wrong – I played Gibsons, too; I loved the fat neck and fat frets, and I loved the way they handled. But I always liked having that vibrato, and Strats weren’t as high-output, so they didn’t distort as much when I plugged them right into the amp.

“I could get a different variety of sounds with a Strat that I couldn’t get from a Gibson. But if I wanted to get a bit more crunch, I’d lean on the Gibson. And there are obviously a lot of photos of me playing Gibson stuff, and I love them, but when I go on vacation, I still grab my Strat.”

I liked the variety of tones the Strat gave me. I always found myself writing more on a Strat, but there’s no doubt I love my Gibsons dearly

Do they travel better?

“It’s much easier to take the neck off of a Strat and put it in my suitcase than to travel with a Les Paul. [Laughs] And when I get there, I can just screw it back together, and then I have a guitar to play while I’m away. But that aside, like I said, I liked the variety of tones the Strat gave me. I always found myself writing more on a Strat, but there’s no doubt I love my Gibsons dearly. I just seem to find myself with a Strat in my hands more often.”

Of Rocks’ 10 songs, you had a hand in five. You seemed to be on fire by that point.

“When we were doing Rocks [1976], like I said before, we came in early, stayed late and often found ourselves in the chair with the producers from beginning to end. We were fascinated with the whole process at that point.

“Steven is an incredibly talented and detail-oriented guy, and I’m just fascinated by the mechanics of, like, ‘What does this box or button do?’ We were really comfortable in the studio by the time we did Rocks. We did the basic tracks at our rehearsal studio in Boston, and we brought a mobile truck up there and had a blast doing it.”

Is that where Rats in the Cellar was recorded?

“Yeah, it was. If you listen to the beginning of the song, it’s one of Brad’s riffs, and then it’s kind of like two guitars doing the same thing. You’ve got Brad swirling in on the left and me swirling in on the right, and then you hear a door slam in the background.

“And that was weird, and totally by accident, because there was this guy who was working on the record with us, and he had gone out to get coffee. When he came back, he didn’t know we were doing a take, and he ended up slamming the door as he came in. But we liked it, so we left it on. [Laughs]”

Looking at 1977’s Draw the Line, I think it has some of your best playing of the ’70s – especially your slide work on Milk Cow Blues.

“When we were young, Tom and I had a garage band back in New Hampshire. And the bass player in that band had a brother who went to the University of Massachusetts in Amherst, and he would come home with a bunch of great records, like Chuck Berry, Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf.

“But he also had this really hard-to-find live record by the Kinks. I remember they did a version of Milk Cow Blues, where I kinda ripped off the Aerosmith version from. The way they did it was totally different from anywhere else, and that’s where I took inspiration from when we were doing Draw the Line.

“They did a cool medley [with the Batman theme and Tired of Waiting], and the guitar was played with a heavy wrist and just sounded so cool. We played it early in the clubs, and so we’d kinda had our version down by the time we did Draw the Line.”

I remember saying, ‘We’re not ready for the ’80s.’ I don’t know why I said that; it was just a vibe or a feeling I had

How did you develop your slide technique?

“I don’t know… I just kind of had a feel for it. But with Milk Cow Blues, I remember having the same type of Danelectro guitar that Jimmy Page used [DC-59]. It was probably the cheapest guitar I had come across; it had this sticky paper with fake wood grain printed on it and was made from some kind of fiberboard. It had two lipstick pickups and a flat-radius neck, which worked great for playing slide.”

Was it Jimmy who inspired you to use the Danelectro?

“No, this was actually before I knew Jimmy played one. I just came across it and thought it would work well for slide because of the flat-radius neck. I kept it tuned to open A, open C or even open G. I kept fooling around with it and never really did get into playing it with standard tuning.

“But the funny thing with the open G tuning, for example, is I found it so hard to write a song that didn’t sound like Keith [Richards]. But anyway, the Danelectro and the Kinks’ version of Milk Cow Blues inspired the Draw the Line version.”

Looking back, did Aerosmith’s sudden success negatively impact the band?

“It was tough, and by the end of the ’70s, the band wasn’t getting along. We certainly had high points, but the other side of it is that Steven and I are known for our legendary fighting and all that shit. But we still went SCUBA diving together and were very close when we were away from the band.

“We were like brothers outside the band, but when we got into the studio or on the road, we’d butt heads. You have to remember, we were really young small-town guys, so it was interesting to grow into young adulthood with guys you had gotten together with just because you thought they were the right musicians.”

How would you describe the state of Aerosmith during the sessions for 1979’s Night in the Ruts?

“The band had issues where sometimes we fought and sometimes we got along. Many problems came when we started having significant others, girlfriends and wives; it was tough.

“Looking back, we didn’t handle it all that well. We just didn’t know how to deal with it at the time, you know? It wasn’t that we didn’t play well together; it was just that we had trouble getting along by that point. I guess that’s why it had to end. I split during Night in the Ruts; I had to get away.”

Do you remember your reasons at the time?

“I just had to take care of myself. My personal life wasn’t all that great, and I had to deal with that. I had come to terms with that and knew it was time to leave. But I also felt we needed to be more open to new ideas. We were rolling into the ’80s, and I still remember hearing the first Van Halen record and fucking loving it. I mean… what a great fucking record.

“Eddie’s guitar playing was just so incredible; he turned guitar on its fucking ear and was doing stuff that I’d never heard before. I knew it was time for a break because new ideas were needed. But we also needed to re-adjust our sights and learn to get along again. I remember saying, ‘We’re not ready for the ’80s.’ I don’t know why I said that; it was just a vibe or a feeling I had.”

I went out and had a great time with the Joe Perry Project for a few years. I had a great bunch of guys, and we played all over the country

Do you regret that in hindsight?

“I’ve always said we would have just taken a break if we had our wits about us. It was probably time to lay low for a bit and reset ourselves, and I guess we did that, but did so in the worst way, which was break up. They carried on without me and Brad, but it was a tough time for them, too.

“But I went out and had a great time with the Joe Perry Project for a few years. I had a great bunch of guys, and we played all over the country. I did some solo records and wrote some great stuff, and maybe some mediocre stuff, too. [Laughs] But the main thing was I got out and played and had a good time doing it. But I did miss the guys in Aerosmith during that time.”

Did you keep up with Aerosmith while you were away from the band?

“Thinking back on Night in the Ruts, that record was a nightmare. But I have to say, it features some of the best playing Aerosmith has ever done in the studio. I remember checking it out after I left, and I was very surprised they left me on it since I left in the middle of it.

“If you look at a song like Cheesecake, the slow slide in the middle, we did that live in the studio, and it’s so great. I think it could have been a huge record if we had the chance to tour behind it. But it was not to be. And so I want to resurrect some of that stuff and play it live. I can envision doing the back-and-forth thing with Brad at the beginning of Chiquita; I think it would go down so well.”

Do you feel leaving Aerosmith kept you from going entirely off the rails?

Even though we didn’t get along, we had a code of honor in Aerosmith. We never got into fistfights; we never stepped over that line to where we couldn’t come back from it

“It’s hard to look at something like that out of context, you know? Maybe if the circumstances were better, and if I’d stayed, we could have gone on to make another record. But the thing is that maybe if we’d stuck together, something terrible would have happened that would have never been repairable, meaning we would never have gotten back together.

“Because even though we didn’t get along, we had a code of honor in Aerosmith. We never got into fistfights; we never stepped over that line to where we couldn’t come back from it. I think we always stopped short of that because deep down, we knew it would be too hard to come back from.

“So looking back on what led up to that, I think it was the only choice. And now that I think about it, the other thing was that our management was not treating us right, and I couldn’t get any support from the other guys.”

How so?

“I always felt like we were making a lot of fucking money for everybody, and we weren’t seeing what we should be seeing. And I couldn’t get the other guys in the band to rally, you know? So that was another big part of the issue that I haven’t talked much about. But looking back on it, yeah, it was a big part of it for me.”

I hadn’t heard that side of it, but I can imagine that, given the band’s success, that must have been incredibly deflating.

“It was. And just to show you just where their heads were at, 10 fucking years after the band got back together, I found out that Columbia Records said, ‘Oh, he’s leaving Aerosmith? Well, we’re going to bury his first solo record. We’ll starve him back to Aerosmith.’

“I was told that our management at the time didn’t think I was that important to Aerosmith. They figured, ‘Eh, he’s just a guitar player, and so is Brad. We’ll get two other guys and nobody will care.’ That shows you how out of touch they were with what Aerosmith was about.”

It’s bewildering to think Aerosmith’s management wouldn’t recognize you and Brad’s importance.

“Yeah, and I always wondered why my solo record didn’t do better. It should have done a little better, considering I had been with Aerosmith and was touring across the States, but it didn’t. And then, with the second record, I was sure it would do better, and sure enough, they buried it. They wouldn’t do anything to push it. It felt good to know that my instincts were right; they just weren’t doing their part to help it along.”

What ultimately calmed the water between you and Steven to where a reunion was possible?

That time away from each other allowed us to realize how much value there was in us being together in a band

“Before I left Aerosmith, we never dealt with stuff. We’d have these major fucking fights, and rather than dealing with something or sorting it out, we just leave or go in the other room. And I think that time away from each other allowed us to realize how much value there was in us being together in a band.

“At the end of the ’70s, truthfully, we weren’t playing our best; we weren’t giving the fans what they were promised. But by ’84, we had taken care of a lot of our stuff; well, I don’t know how Steven felt about it, but as far as I was concerned, my house was not in order when I left. But I had gotten my personal life in order, which was part of why the band didn’t get along prior to it.”

How did the reunion actually go down?

“It was a combination of things. Like I said, I had sorted out my life and met my wife, Billie, who had to run me through the car wash a few times. [Laughs] Meeting her was interesting because she didn’t really know Aerosmith; she was into punk rock. She’d heard the name, but it was just another logo or whatever to her.

“We had this massive career in the ’70s, but she knew maybe two songs. So she was a big part of me sorting my life out. But the other guys still in the band had gone through trying to do Aerosmith without me and Brad, and it’s pretty well documented how that went.

“Even Rick Dufay [the guitarist who replaced Whitford in 1981] said, ‘Listen, you’ve gotta get those guys back in the band. This just isn’t working without them.’ Rick is a really smart, standup guy who was just telling it like he saw it. But Billie encouraged me to get together with Steven, and we hooked up and talked about Aerosmith, and it went from there.”

Would the reunion have happened without Billie?

“She put it in perspective for me. When we first got together, we were driving, and Back in the Saddle came on the radio. I pulled over and said, ‘That’s my song. Have you ever heard it?’ She said, ‘It sounds familiar,’ but she really didn’t know it. She didn’t really understand how big we were in the ’70s, you know?

“But then she went through some of my old boxes and came across old copies of Circus and Creem magazines with us on the cover and old pictures of us playing stadiums, and I think that’s when it hit home for her. I told her we had gold records, but she didn’t understand until she saw the pictures.”

We got back together, but I had one condition: we had to have new management. The rest is history

Were you surprised she hadn’t really heard much of Aerosmith’s stuff?

“Well, it’s not like I walked in saying, ‘Hey, I’m the guy from Aerosmith,’ with my Aerosmith T-shirt on. [Laughs] It was just a chapter in my life, but it was over at that point. But that’s when she said, ‘Why aren’t you guys still together?’ I explained the whole thing to her, and we went to see them in Boston when they were doing a gig, and she met Steven, and it all went from there.

“I could have done another solo record, put another lineup together and toured some more, but we were in a lull, and Aerosmith’s other guitar players weren’t really working out. So we got back together, but I had one condition: we had to have new management. The rest is history.”

You mentioned before that you didn’t feel Aerosmith was ready for the ’80s. Did you change your mind after you returned?

“When we went in to do Done with Mirrors [1985], the whole West Coast hair band thing started, and we were trying to find our place. I remember writing those songs and feeling tentative about the whole thing because we didn’t know how it would be received.

“The whole guitar style had changed from British blues to a sound that was very different, very clean sounding and just different from what we were. We had no idea if we would fit in, and it’s not like any of us were ever going to be called ‘shredders.’ [Laughs]”

I kinda wish Ted had more input because I feel that Done with Mirrors lacks a layer of production... more spice could have been added to it

So there was never a thought of changing who you were?

“No; we had no interest in trying to be like the other bands. We were more about dipping our toes in the water, so to speak. And thankfully, [producer] Ted Templeman, who we found out later was in awe of the whole thing, came along. We loved what he did with Van Halen and thought he would be a good fit.

“So with Done with Mirrors, he basically just turned the machines on and let us go. And looking back, I kinda wish Ted had more input because I feel that Done with Mirrors lacks a layer of production. There was a level of communication that hadn’t been established yet, and more spice could have been added to it.”

Done with Mirrors wasn’t a hit, but the Back in the Saddle Tour most certainly was.

“Oh, yeah, we toured in the summer of ’84 before we did Done with Mirrors. We had been broken up for a few years, were in a new era and went on the road without a record deal. We had to buy our way out of the Columbia Records deal; if you can believe it, we owed them, like, $300,000. After all those records we sold, we owed them money. It was crazy.

“And we had to get out of the management contract the guys had signed before me and Brad returned. So we had made all this fucking money for all these people, and now we’re back together, and we’re already in the red. There were no more chartered planes; we were touring on buses with our wives and girlfriends.

“I can’t tell you how thankful we were that the fans came out to support us on that summer tour. We started again in ’84 with no album or single; they showed up for us just because they wanted to see us play together again. I’ll never forget that, and I don’t think we’d be here if they hadn’t.”

It must have been a real trip rebuilding yourself and the band, finding explosive success again as an older band – who had done it all before – in the heart of the ’80s.

“The fact that we had been through it before in the ’70s helped. I also think we were just young enough to slip in under the wire of the MTV era. If we had been a few years older, I’m not sure it would have worked. But we were able to get in there with Permanent Vacation [1987], and we made a video that did great for Dude (Looks Like a Lady). But that was all new to us, you know?

“The idea of a TV station that played music videos 24/7 was very different from what we did in the ’70s when we only made videos for promotion and played them at trade shows and shit. Defining a song with a video was very new, and putting a picture in people’s minds like that wasn’t something we were sure about, but it was fun.

“We ended up having a great time with the whole MTV thing. Some of the videos for the songs were literal translations of the lyrics, and others were just eye candy and a bunch of fun stuff to watch. [Laughs]”

Speaking of Dude (Looks Like a Lady), your tone on the solo always struck me as unique. What guitar did you use?

“I used a Gretsch Duo Jet sparkle. I used that, and I probably had .10-gauge strings on it. I really wanted to get a lot of bite on the solo, but I also wanted it to fit the song. That song isn’t one of our favorites, but we had a sense of humor about it, and the fans really love it. So it’s always in the setlist. But that song was cool because I could pick and choose the guitar tones that I got on it. Another one like that was Janie’s Got a Gun.”

Brad is a wicked soloist. In my book, some of the best solos in our catalog are ones Brad did

The solo for Janie’s Got a Gun features the same twang. Did you use the Gretsch Duo Jet?

“No, that came about differently than Dude (Looks Like a Lady). With Janie’s Got a Gun, I wanted something angry-sounding. I had this Chet Atkins semi-acoustic guitar with a single cutaway and strings that were on the heavier side. It was a Gibson that was only like two inches thick and had a piezo pickup in it.

“I plugged it into one of those 15-watt Marshall practice amps, turned it all the way up and played it in front of the producer, Bruce [Fairbairn], who hated it. He said, ‘That sounds terrible; it’s just not gonna work.’

“And, I mean, it was pretty raunchy, and we were dealing with all sorts of feedback and shit. But I said, ‘No, let me give it a try,’ and I got this nasty sound that raged coming out. It worked, and in fact, when I was touring, I used that exact same setup for the song.”

Love in an Elevator was huge, too. I believe Brad took the first solo and you played the second one, right?

“Yeah; it just felt like a good place to do that. We’ve always kinda shifted back and forth where maybe Brad takes the first part, I take the second, he takes the third and I take the fourth. That’s basically what we did on Love in an Elevator. And then, during the breakdown, that’s me playing.

“But it’s always rubbed me the wrong way when people put Brad down and only refer to me as the lead guitarist. We’re both guitar players in the band, you know? Brad is a wicked soloist. In my book, some of the best solos in our catalog are ones Brad did.”

That’s a good point. One of the great things about you and Brad as a guitar duo is that there’s no ego.

“Brad is a great guitarist; he really is. I don’t have any schooling, but Brad went to Berklee, so he’s got all that music theory stuff to draw upon. He’s always been great at watching me and adding something that would fit in there well. But we never really talked about who would play what. It was more about who would play a Strat and who would play a Gibson because we wanted to have two different guitar sounds in there.

“And like I said before, most of the time, when I was writing, it would be on a Strat. But Brad was more of a Gibson guy. We wanted to dial in those tones to where they worked together because we were never into having two guitars that sounded the same. In my mind, we could be like the Yardbirds in those rare times when you had Jimmy [Page] and Jeff [Beck] together. That’s what we wanted Aerosmith to be.”

Looking at 1993’s Get a Grip, your tone seemed to harken back to the bluesy sounds you were known for in the ’70s. Was that intentional?

“Yeah, I do think that was kind of what was happening there. I went into Get a Grip thinking I’d look to get a cleaner sound again. If you look at a song like Fever, I remember using a ’66 Gibson Firebird, one of my all-time favorite guitars. It’s the closest Gibson came to having the best of both worlds. It’s meaty-sounding, but it’s got those mini-humbuckers that sound fucking great.”

You mentioned Fever, but can you recall putting together Cryin’?

“We were in A&M Studios, and I remember having a [Marshall] Plexi and a couple of other amps. It was pretty simple; I didn’t wanna mess around much. I wanted to get those tones we discussed before, and I felt like having good amps would help.

“I know I had some old Gibson guitars and some Fenders, but I can’t remember recording the solo for that one specifically beyond the fact that I was really getting back into the cleaner sounds.”

As I understand it, there’s an unreleased version of 1997’s Nine Lives out there that the public hasn’t heard.

“Yeah, that’s true. We had recorded that whole record down in Miami, and we’d spent five or six months working on it with [producer] Glen Ballard, and we couldn’t get a mix down that we really liked. Long story short, when we heard the final rough of it, we didn’t like it.

“It just didn’t sound right, and a big part was because Joey wasn’t on it; he was having some medical issues, and we’d brought Steve Ferrone in to help, but it just didn’t work. And so we got back in the studio with [producer] Kevin Shirley and Joey, and it was totally the opposite experience.

“He had us in the studio playing together live, and we took the same songs and blew through them. It sucks, though, that it took almost a year to make the first version, only to throw it out. I’m actually interested to see if we can go back and mix it and have a whole different take on those songs for people to hear one day.”

2001’s Just Push Play was a massive success. I remember Jaded being everywhere. But I’ve read that it’s your least favorite Aerosmith record.

“Just Push Play was a tough record to do because we were working with outside writers. And I guess we had gotten used to that by then, but I really wanted to get back to spending time with Steven like we did on the earlier records.

“We used to spend a couple of weeks just jamming together, putting ideas down and creating the backbone of what the record would be. And we’d gotten so far away from that by Just Push Play, and I really wanted to get back to it. But it was hard because we’d had outside writers in the picture for a while, and it was tough to go back.”

The best parts of making Just Push Play were seeing the cars in my driveway each day and knowing the guys were together. We had a lot of fun four-wheeling, smoking cigars and hanging out

Has your stance on the record softened?

“I did as much as I could to keep that old vibe going, and when the four of us were together, it worked. But I don’t know; some stuff on there doesn’t sound like Aerosmith to me. Steven was working with Mark Hudson on lyrics and was spending a lot of time in L.A. at that point, so the vibe was different. But, yeah, we managed to get some good tunes on there.

“We experimented with some things, and it was cool to record most of the album at my house at the Boneyard. But the best parts of making that record were seeing the cars in my driveway each day and knowing the guys were together. We had a lot of fun four-wheeling, smoking cigars and hanging out. But musically, there was a lot of pushing and pulling. And there are some songs on there that I could do without, and some songs like Avant Garden that I really like.”

You had nearly a lifetime’s worth of gear at your disposal. Which guitars and amps played the greatest role?

“I probably had like 15 or 20 of my best guitars in the studio while we did Just Push Play, so I’d have to look at some pictures to try and tell you what ones I used on which song. I used maybe a dozen guitars across the album, so it’s hard for me to figure out what I used.

“I had all my foot pedals down there – it was like recording in my fucking warehouse; all my shit was all over. [Laughs] I also had quite a collection of combos and some nice Marshall amps, both new and old. And then I recorded some stuff direct, so it depended on the track.”

Even back when we did Music from Another Dimension, I wasn’t sure we were gonna be able to do another record

It’s been 11 years since 2012’s Music from Another Dimension. You’re still very creative on the solo and Hollywood Vampires side of things, but not Aerosmith. Why is that?

“Even back when we did Music from Another Dimension, I wasn’t sure we were gonna be able to do another record. Everybody had stuff going on, and really, with that record, we did write some new stuff, but a lot of it was stuff that had been around for as long as 20 years before.

“For example, there’s a song called Something I wrote in the early ’90s. And I mainly put it on because I wanted Steven to play drums on it. So if you want to hear what kind of drummer Steven is, give it a listen. [Laughs] But we did the record, put it out there, and then Steven went on to do the TV show [American Idol].

“I was in the middle of working on my solo record, and we weren’t touring as much. We got off doing different things, and over the last few years, it’s been hard to get everyone together to do stuff.”

Is there a plan to make another record?

“I don’t know… it’s really hard to get everybody together to do it. I’m not saying we’ll never make another album, but we’ve got so much happening and so much stuff in the vaults that needs to come out, so we’re focusing on that. I really don’t know… we’ll have to see how it goes after we do this next run.

“We’ve got farewell dates, and we’re focused on that. But you never know what can inspire you. I do know we’ve got to be in the right headspace because there are times when I’d write and I couldn’t get Steven to come down and times when Steven would write, and he couldn’t get me to come down.”

I’m not saying we’ll never make another album, but we’ve got so much happening and so much stuff in the vaults that needs to come out, so we’re focusing on that

Despite a ton of ups and downs, you and Steven have made it work. After 50-plus years together, what’s your secret?

“There’s so much that’s been publicized about us from the ’70s and ’80s, but the truth is we’ve always had respect for each other’s thing. There’s no ‘my way or the highway’ stuff and no debate anymore. We can put our ideas on the table and have the five guys decide.

“Steven and I can talk shit out. If there’s an issue, we’ll figure it out. I can convince him; he can convince me; we can change each other’s minds. That’s huge – that’s why we’re still friends, and it’s why we’re still together. Honestly, we are not probably, but definitely better friends now than ever. That’s no bullshit.”

Andrew Daly is an iced-coffee-addicted, oddball Telecaster-playing, alfredo pasta-loving journalist from Long Island, NY, who, in addition to being a contributing writer for Guitar World, scribes for Bass Player, Guitar Player, Guitarist, and MusicRadar. Andrew has interviewed favorites like Ace Frehley, Johnny Marr, Vito Bratta, Bruce Kulick, Joe Perry, Brad Whitford, Tom Morello, Rich Robinson, and Paul Stanley, while his all-time favorite (rhythm player), Keith Richards, continues to elude him.