“I’ll still be playing guitar – I’ll do that until I can’t – but I’m at the age where my heroes passed away. I’ve gotta keep that in mind”: Buddy Guy opens up on his retirement from the road and 70-year career as a true blues original

On the eve of his farewell tour, a living legend of the blues looks back on why he thought the Stratocaster was a joke, the moment he realized his influence on Hendrix and Clapton, and the advice B.B. King gave him about guitar solos

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

He might not have admitted it then, but when Eli Toscano signed a 22-year-old Buddy Guy to his first recording contract with Cobra Records in 1958, Toscano undoubtedly knew Guy was special.

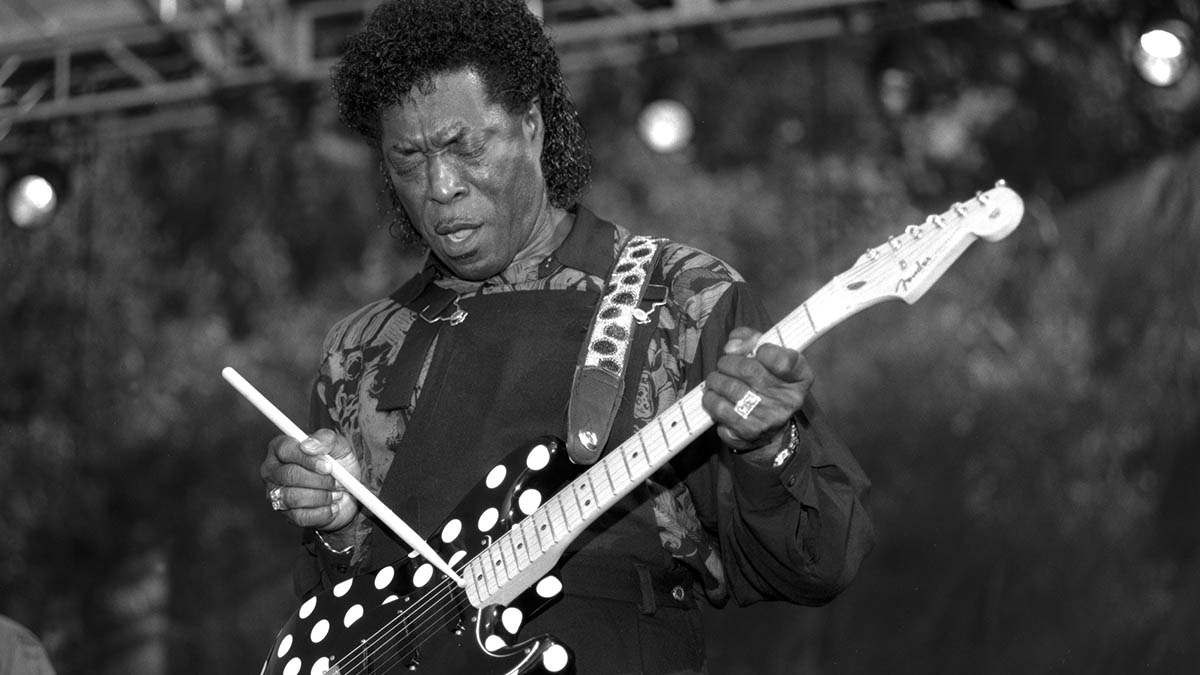

Unlike anyone before him, Guy reshaped the sound of the electric guitar, pushing the blues to its limits in the late ’50s and into the ’60s. Of course, when we look at the now 87-year-old bluesman on stage, years’ worth of polka dot-tinged exploits come to mind.

But in his early days, Guy was as mild-mannered as they come. Profoundly religious and hailing from Lettsworth, Louisiana, Guy’s formative years were more about survival than chasing dreams. But it didn’t take long for Guy to catch on with Cobra and later Chess Records as a session man, a period when he received his “first real education on guitar,” he says.

“I was never someone who would jump out in front of Junior Wells or Muddy Waters,” he adds. “When I walked in, I said, ‘It’s time for me to go to school.’ And that’s what I did. They’d put me in the corner, and when it was time to play, I’d play. And when it was time to learn, I’d learn.”

“But I’ve always been quiet,” Guy says. “I remember going into those studios with all these crazy, loud men who were all yelling. And whenever they’d see me in the morning, the first thing they’d say was, ‘Oh, good morning, motherfucker.’ And then, I’d go back in the corner, and when they needed me, they’d say, ‘Come over here, motherfucker,’ or ‘Turn that guitar up, motherfucker,’ or, ‘Hey, I told you to play this differently, motherfucker. So I was ‘Motherfucker,’ but I remember thinking, ‘Well, shit… I thought my name was Buddy.’”

By the late ’60s, having realized he had captivated the imagination of several young British bluesbreakers, Chess Records turned Guy loose. The result was 1967’s Left My Blues in San Francisco, which saw to it that Guy’s energetic style – which included the innovative use of a Fender Strat and featured hard-rocking yet blues-soaked sounds – was finally allowed to be laid to tape.

But despite his influence, Guy was unable to break through to the mainstream. He soldiered on for another 24 years before going dormant in the ’80s. But in 1991, well past 50, Guy unexpectedly found widespread success with 1991’s Damn Right, I’ve Got the Blues.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Looking back, Guy recalls the difficulties resulting from waiting so long to find success, saying, “It was hard because Damn Right, I’ve Got the Blues was recorded when I was 55. I had gotten used to things being how they were and never expected anything big to come. I came from nothing, and to have Damn Right, I’ve Got the Blues do so well, all I could think was, ‘Well… better late than never.’ I’ve been living by that motto ever since.”

In the years since, Guy has recorded a dozen more records, with 2022’s The Blues Don’t Lie being his most recent. At 87 – a full six years older than Paul McCartney and his generation – Guy’s energy is still infectious, his voice in fine form and his smile as wide as ever.

And so, in early 2023, it came as a bit of a surprise that Guy – a guitarist who has made a habit of playing at least 150 shows a year – announced his farewell tour.

Of course, it had to happen sometime, but considering Guy is a man who has outlasted his contemporaries, the idea of a Buddy Guy-less touring circuit is hard to fathom. But Guy is unfazed, knowing his time in the sun has come and gone. To that end, he elaborates, insisting, “I’m not calling this a full retirement. It’s just time for me to be done with traveling.

“I don’t want to cheat people,” he says. “I have a reputation for giving 100 percent, but I’m 87 now, and I can’t kick my leg as high as I did when I was 27. [Laughs] I’ll still do blues festivals and one-offs, but I can’t tour the world anymore. I’m too old to be jumpin’ from town to town on a bus. I’ll still be playing guitar; I’ll do that until I can’t. And I’ll keep making music, but I’m at the age where my heroes passed away. I’ve gotta keep that in mind.”

It’s comforting to know this isn’t the end of the road for Guy, only an end to his wide-scale touring. Still, the knowledge that one of music’s most effervescent personalities will be globetrotting no more comes with more than a hint of finality.

As for Guy, he, too, is aware of the impending finish line. Having watched the likes of B.B. King, Howlin’ Wolf, Junior Wells and oh so many more strum their final chords and slay their final solos, Guy knows time waits for no-one. Now more than ever, Guy is reflective as he looks back on a career bred through grit and determination.

I remember growing up with people who I won’t name, and we’d be sitting there eating a hot dog together as friends, then they got a hit song, and it was like they had no idea who I was

And while music as we know it will forever show the imprint of Guy’s growling tone, when it comes to special treatment, he is having none of it.

“I remember growing up with people who I won’t name, and we’d be sitting there eating a hot dog together as friends,” he says. “Then they got a hit song, and it was like they had no idea who I was. I’d go up to them, and it was like we were strangers. I didn’t know success could do that, but I swore I’d never do that.

“So I’m still the same Buddy Guy who used to pick cotton and hang out. I ain’t never gonna be someone different. But people sometimes look at me and say, ‘Are you Mr. Guy?’ And I say, ‘No, I’m not Mr. Guy. You can call me Buddy.’ Man, look – I’m just a guitar player who taught himself to play long ago. I never wanted to be treated no better than you or anybody else. I ain’t gonna start now.”

You’ve been performing at a breakneck pace for years. Why stop now?

“Age is something I’ve been thinking about more and more. I watched all the old guys like B.B. King, Howlin’ Wolf and Muddy Waters go until they got old. Often, when you watch older people playing shows, you think, ‘Man… they just don’t sound the way they did when they were younger.’ I remember listening to some of my heroes when they got older and thinking it wasn’t the same. I don’t want someone coming away from my show thinking, ‘He doesn’t sound any good.’”

How vital were guys like B.B. King, Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf in terms of developing your sound?

“They were everything. I would listen to a little bit of everything, man. But it wasn’t just guitar music; if I heard a note on a horn, I’d try to play that with my guitar. If I was listening to gospel, I’d see what I could learn from that. And when B.B. came along, I loved his licks. I wanted to play a few of those licks just like he did, but I also knew I wanted to add something else. I wanted to add a little bit of lighting. I saw the guitar as being almost like Louisiana Gumbo. I put a little bit of everything in.”

Is it true that you signed your first recording contract with Cobra after winning a competition against Magic Sam and Otis Rush?

“A lot of people say that, and I’ve heard it, too. But the way I remember it is I sent a letter to Cobra, and I never heard anything. So I went in there and asked them, 'Did you get my letter?' and they said they never got it. After that, I started playing some of the old blues clubs, and it was around that same time that Magic Sam and Otis Rush showed up.

“And I don’t remember any competition; those guys were always patting me on the back, saying, 'Hey, Buddy, hang in there and keep trying.' I think they were the ones who spoke to the president of Cobra, a guy named Eli [Toscano], saying, 'Man, you had better sign that motherfucker, Buddy Guy.' Well, they signed me, and not long after, I did my first single [Sit and Cry (the Blues)/Try to Quit You Baby].”

No-one wanted Buddy Guy’s name on the sleeve. No, sir. So they came up with the idea of me going by a different name. And they called me 'Friendly Chap'

In your early days, Chess often credited you as “Friendly Chap”. Was that to keep the attention on the bigger artists?

“Yeah, I think so. Those guys were the hit-makers. They had big contracts, and they were the stars, you know? My job was just to back them up. They didn’t want any attention on me. They wanted me to back them up and add whatever they needed for the record. Nothing more than that.

“And when the records came out, no-one wanted Buddy Guy’s name on the sleeve. No, sir. So they came up with the idea of me going by a different name. And they called me 'Friendly Chap.' I think the Chess brothers initially hoped nobody would ever figure out who I was if they called me that. [Laughs]”

It’s said that Cobra and Chess were initially reluctant to allow you to record with the same energy that you brought to your live shows. Why is that?

“I wanted to turn up and add some energy. But they weren’t ready for that. And I can understand why because they made many hit records doing what they did. Having someone like me come along probably scared them. But I’ll never forget something that happened in the ’60s when the Chess brothers sent old Willie Dixon to my house, saying, ‘Go get that boy and bring him back down here.’

They played some Jimi Hendrix and Eric Clapton licks for me, saying, ‘Buddy, these guys got this stuff from you’

“And when I got down there, they had me come to their office, and all I could think was, ‘Oh, boy… they’re gonna get rid of me now. I’ve really done it.’ But they said, ‘Buddy, I want you to kick us in the ass.’ And I said, ‘Why? What’s wrong with you?’ And they played some Jimi Hendrix and Eric Clapton licks for me, saying, ‘Buddy, these guys got this stuff from you.’”

When you started playing in that style, it was far from common. What inspired you to push the limits?

“I had to find my own unique voice on the electric guitar. Because I had heard guys like B.B. King and T-Bone Walker, I said, 'I’ll never be that good. I’ve got to do something different from them or I’m done for.' A guy like Guitar Slim was wild, and B.B. King had a left hand that could do things that were not of this Earth. I knew I could never do any of that. So I told myself, if I can ever become any good at guitar, I’d like to act like Guitar Slim but play like B.B. King and T-Bone Walker.”

In retrospect, many people would argue that you were their equal, if not better.

“I don’t know about that. Those guys had something special that they took with them to the grave. I ain’t never gonna be those guys. I can try, but I ain’t one to ever say I’m that good. But I did find my voice, and Leo Fender’s Stratocaster guitar had a lot to do with that.

“But my first endorsement was with Guild, not Fender – but my amp was a Fender; it was a Bassman. And the first time I played Newport [Jazz Festival], Guild heard my amp, and they told me, ‘Buddy, keep that amplifier; we love the tone. Give it here; we want to take it back to our factory and reproduce it.’

“Man, Guild had that amp at their factory for maybe a year, and they couldn’t find the sound. They returned to me and said, “We can’t figure out what Leo Fender did. Keep that amp, and don’t ever let it go. Whatever he did with that amp is going to die with him.”

Have you changed your settings since then?

“I never messed with that Bassman amp. And after I switched to Fender guitars, I told Leo Fender how special it was, that Guild wanted it and not to mess with it. It sounded so good that all those British guys started using it too. The thing was, though, there was something special about that amp. I think it had something to do with the transformer Leo Fender put in it. Nobody could reproduce it.”

Do you still have that Bassman?

“I had it for years, but it got lost after I did some shows in Africa. I didn’t realize it got left behind until I was on the plane, and I was devastated. I searched and searched for it but couldn’t find it. But then, about five years later, we finally found it. But it had been sitting outside in the wilderness and was all rusted out.

“I had it fixed up, but all the parts were ruined. So when I got it back, it looked alright, but with all the redone electrical parts, it never sounded the same. I’ve still got it. It’s stored away. But I don’t play it much anymore because it doesn’t sound like it did.”

Why did you switch from Guild to Fender?

“The first time I saw a Strat, I thought it was a joke. [Laughs] So I had gone down to New Orleans and saw Guitar Slim playing a Strat, and I had no idea what to make of it. But I realized the hollowbody guitars I was playing needed to be babied because of the weather.

“God forbid one got wet; they’d swell up and break. Then I’d have to get them repaired, and they’d have all these nasty scars all over ‘em like someone was chopping at them with an axe. So I turned to Strats because they didn’t get overwhelmed by the weather. And I’ve stayed with them ever since.”

The first time I saw a Strat, I thought it was a joke

How’d you come up with your classic polka-dot finish?

“My mother would have a stroke with worry whenever I’d go out into the world. At the time, I was working at LSU [Louisiana State University], making nothing. I knew I had to do something different. So I decided to go to Chicago, but my mother was sick over it. So before I left home, I lied to her and said, ‘Don’t worry, I’m going to Chicago. I can make more money there.’

“Then I told her, ‘And when I make some money, I’m gonna drive back down to you in a big polka-dot Cadillac.’ That made her smile. But I regretted it because I never got the chance to tell her that I lied to her before she passed away. So, I said, ‘You know what? I never did get that polka-dot Cadillac, but I can get a polka-dot guitar in her honor.’”

Is it true you were still driving a tow truck to make ends meet before recording Left My Blues in San Francisco?

“Oh, you’d better believe it. I was driving that tow truck because it was the only thing I could do to afford anything. I couldn’t make any money playing the blues until the British guys started getting big. That’s when it came out that they were influenced by all of us guys. I’d play in the clubs, but I wasn’t going to Europe like other black players who made a name for themselves by going there to make money. I had a family and couldn’t do that.

“Only when the British guys came along did playing the blues become an honest living. That’s when we were able to start playing the colleges. Before that, I couldn’t make enough money playing guitar. So I said, ‘I’m gonna drive this tow truck in the daytime to feed my family.’ And I’d play guitar seven nights a week for pennies.”

I couldn’t make any money playing the blues until the British guys started getting big. That’s when it came out that they were influenced by all of us guys

You recorded Left My Blues in San Francisco in 1967 – and 1991’s Damn Right, I’ve Got the Blues was your breakthrough. Do you see either of those as your “definitive” album?

“I don’t know what the people who buy albums think, but I’ve always liked Feels Like Rain [1993] and Skin Deep [2008], which have a lot of songs that people request. I guess maybe those resonated with people. I even like the album I made last year [The Blues Don’t Lie].

“But at my age, people don’t look for anything new; they wanna hear the old stuff. So I try to carry on with the type of music people want to hear and give them the old licks that can make the whole house stand still.”

Regarding solos, is there one guiding principle you carry with you?

“B.B. King once told me that he’d never play the same thing twice. He said, ‘If you come to hear me play, you’ll never hear me play anything as I did before.’ So if you come and see a Buddy Guy show, you won’t hear me intentionally try and do anything note for note. I might hit a note that sounds the same, and maybe it even is the same, but I ain’t tryin’ to. I don’t care if it’s a hit song or one nobody knows; I go with the flow and do what feels right.”

I’ve always been someone who gives everything he has to what he’s doing. When you come to see me, you know you’re getting the best I’ve got

Is there anything you’d go back and change?

“No, I wouldn’t change anything. Whatever I have achieved seems to have come later, but that’s alright. I’ve always been someone who gives everything he has to what he’s doing. When you come to see me, you know you’re getting the best I’ve got.

“I know I ain’t never been the best in town, and I see a lot of guitar players who are 10 times better than me. But I’ve always been the best I can be ‘cause that is all I knew. I never wanted to be the best in town; I just wanted to be the best that Buddy Guy could be.”

What will you miss most about touring?

“Looking at all the good-looking women smiling up at me when I hit the right notes. [Laughs]”

- The Blues Don't Lie is out now via RCA Records.

Andrew Daly is an iced-coffee-addicted, oddball Telecaster-playing, alfredo pasta-loving journalist from Long Island, NY, who, in addition to being a contributing writer for Guitar World, scribes for Bass Player, Guitar Player, Guitarist, and MusicRadar. Andrew has interviewed favorites like Ace Frehley, Johnny Marr, Vito Bratta, Bruce Kulick, Joe Perry, Brad Whitford, Tom Morello, Rich Robinson, and Paul Stanley, while his all-time favorite (rhythm player), Keith Richards, continues to elude him.